Complex Odontogenic Infections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural History of Odontogenic Infection

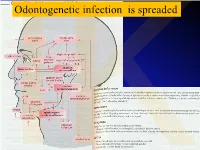

Natural History of Odontogenic Infection The usual cause of odontogenic infections is necrosis of the pulp of the tooth, which is followed by bacterial invasion through the pulp chamber and into the deeper tissues. Necrosis of the pulp is the result of deep caries in the tooth, to which the pulp responds with a typical inflammatory reaction. Vasodilation and edema cause pressure in the tooth and severe pain as the rigid walls of the tooth prevent swelling. If left untreated the pressure leads to strangulation of the blood supply to the tooth through the apex and consequent necrosis. The necrotic pulp then provides a perfect setting for bacterial invasion into the bone tissue. Once the bacteria have invaded the bone, the infection spreads equally in all directions until a cortical plate is encountered. During the time of intrabony spread, the patient usually experiences sufficient pain to seek treatment. Extraction of the tooth (or removal of the necrotic pulp by an endodontic procedure) results in resolution of the infection. Direction of Spread of Infection The direction of the infection's spread from the tooth apex depends on the thickness of the overlying bone and the relationship of the bone's perforation site to the muscle attachments of the jaws. If no treatment is provided for it, the infection erodes through the thinnest, nearest cortical plate of bone and into the overlying soft tissue. If the root apex is centrally located, the infection erodes through the thinnest bone first. In the maxilla the thinner bone is the labial-buccal side; the palatal cortex is thicker. -

Accidental Displacement of Mandibular Third Molar Root Into the Submandibular Space: a Case Report

Case Report ERA’S JOURNAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH VOL.6 NO.1 ACCIDENTAL DISPLACEMENT OF MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR ROOT INTO THE SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE: A CASE REPORT Mayur Vilas Limbhore, Viren S Patil, Shandilya Ramanojam, Vrushika Mahajan, Pallavi Rathi, Kisna Tadas Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College, Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 Received on : 01-04-2018 Accpected on : 10-04-2018 ABSTRACT Address for correspondence Accidental displacement of an impacted third molar, either a crown, Dr. Mayur Vilas Limbhore root piece, or the entire tooth, is a rare complication that occurs Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during surgical removal. The most common sites of dislodgment of an impacted mandibular third molar root are the submandibular, Bharati Vidyapeth Dental College, sublingual and pterygomandibular spaces. Removal of a displaced Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 root from these spaces may be complex due to poor visualization Email: [email protected] and limited access. A thorough evaluation of all significant risk Contact no: +91-8552887325 factors must be performed in advance to prevent complications. This case report reveals the management of accidental displaced mandibular third molar root into the submandibular space. An 39 years-old male patient underwent a third mandibular molar extraction. Accidentally, the mandibular right third molar distal root was displaced into the submandibular space, making necessary a second surgical step. After 2 days awaiting an asymptomatic health status, the second surgical step was successfully performed using multislice CBCT as preoperative imaging guide. The present case report highlights the clinical usefulness of CBCT in proper treatment of the patient. -

Ludwig's Angina: Causes Symptoms and Treatment

Aishwarya Balakrishnan et al /J. Pharm. Sci. & Res. Vol. 6(10), 2014, 328-330 Ludwig’s Angina: Causes Symptoms and Treatment Aishwarya Balakrishnan,M.S Thenmozhi, Saveetha Dental College Abstract : Ludwigs angina is a disease which is characterised by the infection in the floor of the oral cavity. Ludwig's angina is also otherwise commonly known as "angina". Previously this disease was deemed as fatal but later on it was concluded that with proper treatment this infection can be removed and the pateint can recover. It mostly occurs in adults and children are not affected by this disease. As the infection spreads further it would affect the wind pipe and lead to swellings of the neck. The skin around the neck would also be infected severely and lead to redness. The individual would mostly be febrile during this time. Since the airway is blocked the individual would suffer from difficulty in breathing. If the infection spreads to the internal ear then the individual may have audio impairment. The main cause for this disease is dental infections caused due to improper dental hygiene. Keywords: Ludwigsangina ,trasechtomy, fiberoptic intubation INTRODUCTION: piercing(6)(8)(7). In a study that was conducted on 16 Ludwig's angina, otherwise known as Angina Ludovici, is a different patients suffering from ludwigs angina, serious, potentially life-threatening cellulitis, or connective Odontogenic infection was the commonest aetiologic factor tissue infection, of the floor of the mouth, usually occurring observed in 12 cases (75%), trauma was responsible for 2 in adults with concomitant dental infections and if left (12.5%) while in the remaining 2 patients (12.5%) the untreated, may obstruct the airways, necessitating cause could not be determined. -

CASE REPORT Fibromatosis of Infratemporal Space Riaz Ahmed Warraich, Tooba Saeed, Nabila Riaz, Asma Aftab

217 CASE REPORT Fibromatosis of infratemporal space Riaz Ahmed Warraich, Tooba Saeed, Nabila Riaz, Asma Aftab Abstract chemotherapy or non-cytotoxic drugs are also Fibromatosis is a rare benign mesenchymal neoplasm considerable modalities for AF management, to avoid which primarily originates in the muscle, connective sacrifising functional integrity as a price of attaining tissue, fascial sheaths, and musculoaponeurotic tumour-free margins. 3 structures. It is commonly seen as abdominal tumour but Case Report in maxillofacial region, the occurrence of these tumours is very rare and exceedingly rare in infratemporal space. A 35-year-old female visited Oral and Maxillofacial Often misdiagnosed due to its varied clinical behaviour, Department of Mayo Hospital on October 5, 2014. Written fibromatosis is benign, slow-growing, infiltrative tumour informed consent was obtained from the patient for without any metastatic potential, but is locally aggressive publication of this report and accompanying images. Her causing organ dysfunction along with high recurrence chief complaint was of progressive reduction in mouth rate. We report a case of fibromatosis involving the left opening gradually for the preceding 4 years. Medical infratemporal space in a 35-year-old female who history revealed that she had extra pulmonary presented with chief complaint of limited mouth opening tuberculous lesion in left side of her neck which was for the preceding 4 years. treated 10 years earlier. Clinical examination revealed slight thickening and fibrosis of left cheek with zero Keywords: Aggressive fibromatosis, Infratemporal, mouth opening. Overlying skin was normal. There was no Benign, Infiltrative. Introduction Aggressive fibromatosis (AF) or extra-abdominal desmoid tumours are rare tumours of fibroblastic origin involving the proliferation of cytologically benign fibrocytes. -

Anatomical Overview

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

29360-Oral Cavity Dr. Alexandra Borges.Pdf

ORAL CAVITY: ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGIES Alexandra Borges, MD COI Disclosure Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa I have nothing to disclose Champalimaud Foundation Lisbon, Portugal ECHNNR 2021 ECHNNR 2021 MR ANATOMY LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Become familiar with OC anatomy and the importance of using adequate terminology when reporting OC studies NASOPHARYNX NASAL CAVITY • Learn how to tailor imaging studies • Understand the different patterns of malignant tumor spread according to the different tumor subsites OROPHARYNX ORAL CAVITY HYPOPHARYNX BOUNDARIES CONTENTS: ORAL TONGUE Superior: • hard palate • superior alveolar ridge Inferior: • floor of the mouth • inferior alveolar ridge ITM Laterally: • cheeks and buccal mucosaosa Anterior: • Lips Posterior: • oropharynx ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic tongue muscles EM: Styloglossus tongue retraction and elevation Styloglossus Palatoglossus Hyoglossus SG Geniglossus HG GG CN XII CN X EM: Palatoglossus elevation of the tongue EM: Hyoglossus tongue depression and retraction EM: Genioglossus tongue protrusion ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic muscles GG GH TONGUE INNERVATION ORAL CAVITY IX sensitive and Spatial subdivision taste CN X Motor • Mucosal area • Tongue root • Sublingual space CN XII Motor • Submandibular space Lingual nerve: Sensitive (branch of V3) • Buccomasseteric region Taste (chorda tympani) ORAL MUCOSAL SPACE ROOT OF THE TONGUE 1. Lips 2. Gengiva (sup. alveolar ridge) 3. Gengiva (inf. alveolar ridge) 4. Buccal 5. Palatal 6. Sublingual/FOM 7. Retromolar trigone GG 8. Tongue ROT BOT Vestibule GH Mucosa -

Head & Neck Surgery Course

Head & Neck Surgery Course Parapharyngeal space: surgical anatomy Dr Pierfrancesco PELLICCIA Pr Benjamin LALLEMANT Service ORL et CMF CHU de Nîmes CH de Arles Introduction • Potential deep neck space • Shaped as an inverted pyramid • Base of the pyramid: skull base • Apex of the pyramid: greater cornu of the hyoid bone Introduction • 2 compartments – Prestyloid – Poststyloid Anatomy: boundaries • Superior: small portion of temporal bone • Inferior: junction of the posterior belly of the digastric and the hyoid bone Anatomy: boundaries Anatomy: boundaries • Posterior: deep fascia and paravertebral muscle • Anterior: pterygomandibular raphe and medial pterygoid muscle fascia Anatomy: boundaries • Medial: pharynx (pharyngobasilar fascia, pharyngeal wall, buccopharyngeal fascia) • Lateral: superficial layer of deep fascia • Medial pterygoid muscle fascia • Mandibular ramus • Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland • Posterior belly of digastric muscle • 2 ligaments – Sphenomandibular ligament – Stylomandibular ligament Aponeurosis and ligaments Aponeurosis and ligaments • Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis: separates parapharyngeal spaces to two compartments: – Prestyloid – Poststyloid • Cloison sagittale: separates parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space Aponeurosis and ligaments Stylopharyngeal aponeurosis Muscles stylohyoidien Stylopharyngeal , And styloglossus muscles Prestyloid compartment Contents: – Retromandibular portion of the deep lobe of the parotid gland – Minor or ectopic salivary gland – CN V branch to tensor -

Diapositiva 1

Ingegneria delle tecnologie per la salute Fondamenti di anatomia e istologia Lezione 4.a.b.c aa. 2018-19 Ingegneria delle tecnologie per la salute Fondamenti di anatomia e istologia aa. 2018-179 Sistema locomotore • Ossa 4.a • Articolazioni 4.b • Muscoli 4.c BONES 4.a BONE TISSUE & SKELETAL SYSTEM After this lesson, you will be able to: • List and describe the functions of bones • Describe the classes of bones • Discuss the process of bone formation and development Functions of the Skeletal System Bone (osseous tissue) = hard, dense connective tissue that forms most of the adult skeleton, the support structure of the body. Cartilage = a semi-rigid form of connective tissue, in the areas of the skeleton where bones move provides flexibility and smooth surfaces for movement. Skeletal system = body system composed of bones and cartilage and performing following functions: • supports the body • facilitates movement • protects internal organs • produces blood cells • stores and releases minerals and fat Bone Classification 206 bones composing skeleton, divided into 5 categories based on their shapes ( distinct function) Bone Classification Bone Structure Bone tissue differs greatly from other tissues in the body: is hard (many of its functions depend on this hardness) and also dynamic (its shape adjusts to accommodate stresses). histology gross anatomy Gross Anatomy of Bone structure of a LONG BONE, 2 parts: 1. diaphysis: tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone, where the hollow region is called medullary cavity (filled with yellow marrow) and the walls are composed of dense and hard compact bone 2. -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

Rediscovering the Rhetoric of Women's Intellectual

―THE ALPHABET OF SENSE‖: REDISCOVERING THE RHETORIC OF WOMEN‘S INTELLECTUAL LIBERTY by BRANDY SCHILLACE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Christopher Flint Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ________Brandy Lain Schillace___________________________ candidate for the __English PhD_______________degree *. (signed)_____Christopher Flint_______________________ (chair of the committee) ___________Athena Vrettos_________________________ ___________William R. Siebenschuh__________________ ___________Atwood D. Gaines_______________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) ___November 12, 2009________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii Table of Contents Preface ―The Alphabet of Sense‖……………………………………...1 Chapter One Writers and ―Rhetors‖: Female Educationalists in Context…..8 Chapter Two Mechanical Habits and Female Machines: Arguing for the Autonomous Female Self…………………………………….42 Chapter Three ―Reducing the Sexes to a Level‖: Revolutionary Rhetorical Strategies and Proto-Feminist Innovations…………………..71 Chapter Four Intellectual Freedom and the Practice of Restraint: Didactic Fiction versus the Conduct Book ……………………………….…..101 Chapter Five The Inadvertent Scholar: Eliza Haywood‘s Revision -

Infratemporal Abscess in an Adolescent Following a Dental Procedure

Central Annals of Pediatrics & Child Health Research Article *Corresponding author Vijay CS, Department of Pediatrics, West Virginia University, Medical Center Dr, Morgantown, USA, Tel: 304-293-6307; Fax: 304-293-1216; Email: Infratemporal Abscess in an Submitted: 30 November 2018 Adolescent Following a Dental Accepted: 02 January 2019 Published: 04 January 2019 ISSN: 2373-9312 Procedure Copyright © 2019 Vijay et al. Vijay CS* and Chen CB OPEN ACCESS Department of Pediatrics, West Virginia University, USA Keywords • Abscess Abstract • Infratemporal fossa Infections in the infratemporal region can be a major source of morbidity and have • Odontogenic infections been known to occur after dental procedures. Neurovascular structures running through the infratemporal fossa serve as a source for infections to track to different areas of the head and neck. The proximity of the infratemporal fossa to other major structures makes timely diagnosis critical. Infratemporal fossa abscesses are a rare complication and only a few cases have been described in the literature. As the clinical symptoms may be non-specific, the diagnosis may be challenging for healthcare providers. We describe a patient who presented with facial swelling and trismus following wisdom tooth extraction who was found to have an infratemporal fossa abscess. ABBREVIATIONS CASE PRESENTATION CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance A 14-year-old previously healthy male presented with Imaging left-sided facial swelling and jaw stiffness. He complained of associated tenderness to palpation over the left side of his face INTRODUCTION The infratemporal fossa is an extremely important site, as it initially started three days after he had four wisdom teeth communicates with several surrounding structures including the extracted.and jaw and As his difficulty symptoms opening did not his resolve, mouth. -

Severe Cervicofacial Infection of Dental Origin

Global Research Journal of Medical Sciences Vol.2(3) pp.038 – 042 October 2012 Available online http://www.globalresearchjournals.org/journal/?id=grjms Copyright ©2012 Global Research Journals Case Study. SEVERE CERVICOFACIAL INFECTION OF DENTAL ORIGIN Dr. A.C Obiadazie 1.Dr. D.S Adeola 2.Dr. Bassey Godwin Obi 3. 1,2 Maxillofacial Unit , ABUTH, Zaria. 3Maxillofacial Unit, University Of Calabar Teaching Hospital. 2Corresponding author’s E-mail : [email protected] , Tel +234 (0)62 218788 GSM +234 (0)80 37189654 Accepted 20 th August 2012. Objective: To highlight severe cervicofacial infection of dental origin as an important health problem in Northern Nigeria. Method: This is a prospective control study of 26 patients (twenty six) with severe cervicofacial infection of dental origin managed at the maxillo-facial department of Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital Zaria between January 2006 to December 2010 Result: Nineteen (19) of the twenty six patients were males and seven females; the age range is between 25 to 68 years. Nine (9) cases result from odontogenic causes while seventeen (17) occurred from post-operative dental complications. Conclusion: Extraction from unqualified personnel (quacks) contributed immensely to the cause of severe cervicofacial infection of dental origin in this area Keywords : Tissue spaces, abscess, antibiotics, Cervicofacial, Northern Nigeria. INTRODUCTION anaemia, gastroenteritis, any debilitating illness, as well as by increased resistance of micro-organisms to usual The diagnosis and treatment of severe cervicofacial antibiotics with wide spectrum (Daniel et al .,1983;Deji et infection represents a challenging problem to the oral and al.,1989; Brook and Hirokawa,1989) maxillofacial surgeon.