Aetio-Pathogenesis and Clinical Pattern of Orofacial Infections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidental Displacement of Mandibular Third Molar Root Into the Submandibular Space: a Case Report

Case Report ERA’S JOURNAL OF MEDICAL RESEARCH VOL.6 NO.1 ACCIDENTAL DISPLACEMENT OF MANDIBULAR THIRD MOLAR ROOT INTO THE SUBMANDIBULAR SPACE: A CASE REPORT Mayur Vilas Limbhore, Viren S Patil, Shandilya Ramanojam, Vrushika Mahajan, Pallavi Rathi, Kisna Tadas Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery Bharati Vidyapeeth Dental College, Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 Received on : 01-04-2018 Accpected on : 10-04-2018 ABSTRACT Address for correspondence Accidental displacement of an impacted third molar, either a crown, Dr. Mayur Vilas Limbhore root piece, or the entire tooth, is a rare complication that occurs Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery during surgical removal. The most common sites of dislodgment of an impacted mandibular third molar root are the submandibular, Bharati Vidyapeth Dental College, sublingual and pterygomandibular spaces. Removal of a displaced Katraj, Pune, Maharashtra, India-411030 root from these spaces may be complex due to poor visualization Email: [email protected] and limited access. A thorough evaluation of all significant risk Contact no: +91-8552887325 factors must be performed in advance to prevent complications. This case report reveals the management of accidental displaced mandibular third molar root into the submandibular space. An 39 years-old male patient underwent a third mandibular molar extraction. Accidentally, the mandibular right third molar distal root was displaced into the submandibular space, making necessary a second surgical step. After 2 days awaiting an asymptomatic health status, the second surgical step was successfully performed using multislice CBCT as preoperative imaging guide. The present case report highlights the clinical usefulness of CBCT in proper treatment of the patient. -

Unlikely Case of Submasseteric Abscess Originating from a Maxillary Molar: the Skipping Lesion

Submasseteric abscess Unlikely case of submasseteric abscess originating from a maxillary molar: The skipping lesion Abstract Objective Min Jim Lima & Alauddin Muhamad Husinb We report a case of submasseteric abscess originating from a maxillary tooth, complicated by underlying diabetes mellitus and a multidrug- a Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hospital Tanah Merah, Tanah Merah, Kelantan, Malaysia resistant organism. b Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Hospital Sultanah Nur Zahirah, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia Materials and methods Corresponding author: A 61-year-old male patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus presented with swelling on the left cheek of 2 weeks in duration with rapid Dr. Min Jim Lim Oral Maxillofacial Surgery Department progression to trismus, dysphagia and rupture of swelling with pus Hospital Tanah Merah discharge. Culture and sensitivity testing revealed the presence of 17500 Tanah Merah Klebsiella pneumoniae Kelantan multidrug- resistant . Based on the patient’s history Malaysia and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of submasseteric abscess originat- [email protected] ing from the maxillary molar was made. Antibiotic administration, con- trol of systemic disease and wound dressing were done as treatment. How to cite this article: Result Lim MJ, Muhamad Husin A. Unlikely case of submasseteric abscess originating from a maxillary The patient made a full recovery, with scarring on the ruptured region. molar: The skipping lesion. J Oral Science Rehabilitation. 2018 Dec;4(4):52–55. Conclusion Submasseteric abscess is a rare case of infection that can occur in the submasseteric space. As is commonly known, infection of the submas- seteric space originates from mandibular third molars; hence, maxillary molars seem to be an unlikely source of infection. -

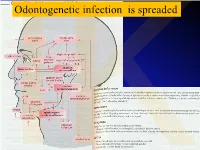

Anatomical Overview

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table

Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 1 Wilson C. Foreign bodies left in the Case series of foreign bodies left in the abdomen. Cases VC Literature n/a n/a n/a n/a Retained abdomen after laparotomy. Trans Am found through publication, interviews, and the author's own Review, Clinician sponges Gynecol Soc. 1884;9:94-117. experience. Experience, and Case Report 2 The Joint Commission. Preventing The Joint Commission recommends that facilities develop IVB Consensus n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a unintended retained foreign objects. effective processes and procedures for preventing Sentinel Event Alert. October 17, unintended retained foreign objects. Their recommendations 2013;51. include a standardized and highly reliable counting system; http://www.jointcommission.org/sea_i development of policies and procedures; practices for ssue_51/. Accessed November 10, counting, wound opening, and closing procedures; 2015. performance of intraoperative radiographs; use of effective communication to include briefings and debriefings; documentation of counts; and assistive technologies (ie, RF tags, RFID, radiopaque, bar coding). Also, the hospital should define a process for conducting RCA for sentinel events, such as URFO. Page 1 of 60 Guideline for Prevention of Retained Surgical Items Evidence Table CITATION CONCLUSION(S) SAMPLE SIZE REFERENCE # POPULATION COMPARISON EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTIONS CONSENSUS SCORE OUTCOME MEASURE 3 Moffatt-Bruce SD, Cook CH, Steinberg 7 elevated risk factors for RSI in pooled data in case-control IIIA Systematic USA hospitals, n/a n/a 3 studies: Estimated SM, Stawicki SP. -

29360-Oral Cavity Dr. Alexandra Borges.Pdf

ORAL CAVITY: ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGIES Alexandra Borges, MD COI Disclosure Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa I have nothing to disclose Champalimaud Foundation Lisbon, Portugal ECHNNR 2021 ECHNNR 2021 MR ANATOMY LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Become familiar with OC anatomy and the importance of using adequate terminology when reporting OC studies NASOPHARYNX NASAL CAVITY • Learn how to tailor imaging studies • Understand the different patterns of malignant tumor spread according to the different tumor subsites OROPHARYNX ORAL CAVITY HYPOPHARYNX BOUNDARIES CONTENTS: ORAL TONGUE Superior: • hard palate • superior alveolar ridge Inferior: • floor of the mouth • inferior alveolar ridge ITM Laterally: • cheeks and buccal mucosaosa Anterior: • Lips Posterior: • oropharynx ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic tongue muscles EM: Styloglossus tongue retraction and elevation Styloglossus Palatoglossus Hyoglossus SG Geniglossus HG GG CN XII CN X EM: Palatoglossus elevation of the tongue EM: Hyoglossus tongue depression and retraction EM: Genioglossus tongue protrusion ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic muscles GG GH TONGUE INNERVATION ORAL CAVITY IX sensitive and Spatial subdivision taste CN X Motor • Mucosal area • Tongue root • Sublingual space CN XII Motor • Submandibular space Lingual nerve: Sensitive (branch of V3) • Buccomasseteric region Taste (chorda tympani) ORAL MUCOSAL SPACE ROOT OF THE TONGUE 1. Lips 2. Gengiva (sup. alveolar ridge) 3. Gengiva (inf. alveolar ridge) 4. Buccal 5. Palatal 6. Sublingual/FOM 7. Retromolar trigone GG 8. Tongue ROT BOT Vestibule GH Mucosa -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. The space contains mostly loose areolar tissue. -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

Methodical Complex on Gross Anatomy for Ii Course

MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION OF UZBEKISTAN BUKHARA STATE MEDICAL INSTITUTE NAMED AFTER ABU ALI IBN SINO DEPARTMENT OF ANATOMY "APPROVED" by Vice-Rector for Academic and educational work, Associate prof. G.J.Jarilkasinova ________________________________ "_____" ________________ 2020 Area of knowledge: 500000 - Health and social care Education field: 510000 - Healthcare Educational direction: 5510100 - Medical business 5111000 - Professional education (5510100 - Medicine business) 5510200 - Pediatric Medicine 5510300 - Medico-prophylactic business 5510400 – Dentistry (by directions) 5510900 – Medico-biological business EDUCATIONAL - METHODICAL COMPLEX ON GROSS ANATOMY FOR II COURSE Bukhara 2020 The scientific program was approved by the Resolution of the Coordination Council No. ___ of August ___, 2020 on the activities of educational and methodological associations in the areas of higher and secondary special and vocational education. The teaching and methodical complex was developed by order of the Ministry of Higher and Secondary Special Education of the Republic of Uzbekistan dated March 1, 2017 No. 107. Compilers: Radjabov A.B. - Head of the Department of Anatomy, Associate Professor Khasanova D.A. - Assistant of the Department of Anatomy, PhD Bobomurodov N.L. - Associate Professor of the Department of Anatomy Reviewers: Davronov R.D. - Head of the Department Histology and Medical biology, Associate Professor Djuraeva G.B. - Head of the Department of the Department of Pathological Anatomy and Judicial Medicine, Associate Professor The working educational program for anatomy is compiled on the basis of working educational curriculum and educational program for the areas of 5510100 - Medical business. This is discussed and approved at the department Protocol № ______ of "____" _______________2020 Head of the chair, associate professor: Radjabov A.B. -

Post-Operative Computed Tomography Scans in Severe Cervicofacial

Post-operative computed tomography scans in severe cervicofacial infections Yanga Ngcwama 9508272 Supervisor: Prof JA Morkel 1 CONTENTS Title 3 Declaration 4 Acknowledgements 5 Dedication 6 List of abbreviations 7 Key words 7 Abstract 8 List of tables 9 List of figures 10 1. Introduction 11 2. Literature review 12 3. Aims and objectives 24 4. Materials and methods 25 5. Results 28 6. Discussion 34 7. Conclusion 37 8. References 38 9. Annexures Annexure 1: Patient Information Letter 41 Annexure 2: Consent Form 42 Annexure 3: Patient Consent to Clinical Photography 43 Annexure 4: Data Capturing Sheet 44 2 TITLE Post-operative computed tomography scans in severe cervicofacial infections By Yanga Ngcwama Submitted in partial fulfillment (mini-thesis) for the Magister Chirurgiae Dentium (Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery) Department of Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery at the Faculty of Dentistry University of the Western Cape June 2015 3 DECLARATION I, Yanga Ngcwama, declare that this mini-thesis is my own work, that all sources I have quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of references, and that it has not been presented for any other degree at any university: Signed: Date: 08 October 2015. Department of Maxillo-Facial and Oral Surgery Faculty of Dentistry University of the Western Cape South Africa 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge my sincere gratitude to the following individuals for their assistance in this research project. (1) Professor J.A. Morkel, for going more than an extra mile in assisting his registrars with their training and their research projects. Long Live. (2) Professor G. -

The Oromaxillofacial Rehabilitation in Orthodontic-Surgical Protocols

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2015044 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2016;19:203 © The authors The oromaxillofacial rehabilitation in orthodontic-surgical protocols Th. Gouzland1,2, M. Fournier1 1 Kinesiologist, specializing in oromaxillofacial rehabilitation 2 Educator SUMMARY Oro-maxillo-facial rehabilitation is an ancient practice that has developed over recent years through research and integration with physiotherapists in multidisciplinary teams, as is the case with orthodontic- surgical procedures. At the same time, the progress made in orthognathic and orthodontic surgery over the last 20 years encourages more and more patients to undergo surgery. Preoperative treatment is based on early assessment and preparation for optimal surgical conditions to come up with a functional plan. A short stay in a hospital, focusing on rehabilitation, is recommended. During the postoperative phase, the key objectives are to ensure the muscles and arteries all function perfectly, acceptance of the new face, and the immediate correction of any orofacial dyspraxia that has occurred during myofunc- tional therapy. The various specialists in this multidisciplinary team must constantly be in communication. The importance of postoperative physiotherapy will be illustrated by a study consisting of 35 cases of maxillomandibular osteotomy with orthodontic preparation and monitoring. The purpose of this study is to show occurrence of suboccipital and cervical muscle tensions as well as masticatory muscles. Then we will be able to see the importance of these practices, the impact on recovery, the impact on posture and how best to treat. KEYWORDS Physiotherapy, orthognathic surgery, orthodontic, myofunctional therapy, muscles, posture INTRODUCTION The progress made in the techniques and comfortable recovery. This fits into and the results obtained by coupling the current social view where one’s orthognathic surgery with orthodontics image is given greater importance. -

Anatomy of the Pterygomandibular Space — Clinical Implication and Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 79 Vol. LIII, 1, 2013: 79–85 PL ISSN 0015-5616 MARCIN LIPSKI1, WERONIKA LIPSKA2, SYLWIA MOTYL3, Tomasz Gładysz4, TOMASZ ISKRA1 ANATOMY OF THE PTERYGOMANDIBULAR SPACE — CLINICAL IMPLICATION AND REVIEW Abstract: A i m: The aim of this study was to present review of the pterygomandibular space with some referrals to clinical practice, specially to the methods of lower teeth anesthesia. C o n c l u s i o n s: Pterygomandibular space is a clinically important region which is commonly missing in anatomical textbooks. More attention should be paid to it both from theoretical and practical point of view, especially in teaching the students of first year of dental studies. Key words: pterygomandibular space, Gow-Gates anesthesia, inferior alveolar nerve. INTRODUCTION Numerous cranial regions have been subjects of various anatomical and anthro- pological studies [1, 2]. Most of them indicate necessity of undertaking of such studies first of all because of clinical importance [3–5]. Inferior alveolar nerve blocs, one of the most common procedures in dentistry requires deep anatomical knowledge of the pterygomandibular space [6, 7]. This space is a narrow gap, which contains mostly loose areolar tissue. It communi- cates however through the mandibular foramen with the mandibular canal, which is traversed by inferior alveolar nerve, artery and comitant vein (IANAV). Many of the structures placed in this space are of certain importance for local anesthesia. Khoury at al. [8, 9] mention here the following: inferior alveolar nerve, artery and vein, lingual nerve, nerve to mylohyoid and the sphenomandibular ligament. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental