Peace and Unification in Korea and International Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

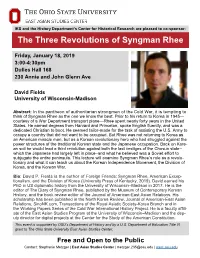

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

Georgetown University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics

INSTANT MESSAGING IN KOREAN FAMILIES: CREATING FAMILY THROUGH THE INTERPLAY OF PHOTOS, VIDEOS, AND TEXT A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics By Hanwool Choe, M.A. Washington, D.C. February 27, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Hanwool Choe All Rights Reserved ii INSTANT MESSAGING IN KOREAN FAMILIES: CREATING FAMILY THROUGH THE INTERPLAY OF PHOTOS, VIDEOS, AND TEXT Hanwool Choe, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Cynthia Gordon, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Extending previous research on family interaction (e.g., Tannen, Kendall, and Gordon 2007; Gordon 2009) and online multimodal discourse (e.g., Gordon forthcoming), I use interactional sociolinguistics to analyze instant messages exchanged among members of Korean families(-in-law). I explore how family talk is formulated and fostered online through technological affordances and multimodalities. Data are drawn from 5 chatrooms of 5 Korean families(-in-law), or 17 adult participants, on KakaoTalk, an instant messaging application popular in South Korea. In their instant messaging, family members accomplish meaning-making through actions and interactions, between online and offline, and with visuals and texts. This analysis employs the notion of "entextualization" (Bauman and Briggs 1990; Jones 2009), or the process of extracting and relocating (a part of) discourse, actions, materials, and media into a new context. I suggest that this meaning-making process -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Confidence And/Or Control? Seeking a New Relationship Between North

Hans-Joachim Schmidt Confidence and/or Control? Seeking a new relationship between North and South Korea PRIF Reports No. 62 ã Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2002 Correspondence to: HSFK Leimenrode 29 60322 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49 (0)69/95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69/55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:/www.hsfk.de Translation: Katharine Hughes MA, Oxford ISBN: 3-933293-64-2 € 10,– Summary The final curtain has not yet fallen on the East-West conflict in the Korean peninsula. The heavily armed forces of North and South Korea are still at a stand-off, with almost two million soldiers, supported by 37,000 US troops on the South Korean side. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, which led to the partition of Korea, both countries find themselves technically still at war. So far, there has merely been a cease-fire in force. While South Korea has since developed into a stable democracy and one of the most economically advanced nations in Asia, the Stalinist rule in the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) is threatening to disintegrate. The economic situation there deteriorated drastically during the 1990s due to economic mismanagement and a number of natural disasters. Despite this worsening economic plight, North Korea possesses the world’s fifth largest army, with almost 1.2 million soldiers, and spends 25-33 % of its GNP on military defence (South Korea spends approx. 3 %). This fuels the fear that the Communist regime in the DPRK could very soon collapse. -

North Korea Country Report BTI 2008

BTI 2008 | North Korea Country Report Status Index 1-10 2.46 # 122 of 125 Democracy 1-10 2.70 # 120 of 125 Ä Market Economy 1-10 2.21 # 122 of 125 Ä Management Index 1-10 1.90 # 122 of 125 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2008. The BTI is a global ranking of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economic systems as well as the quality of political management in 125 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. The BTI is a joint project of the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Center for Applied Policy Research (C•A•P) at Munich University. More on the BTI at http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/ Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2008 — North Korea Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2007. © 2007 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2008 | North Korea 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 22.5 HDI - GDP p.c. $ - Pop. growth1 % p.a. 0.5 HDI rank of 177 - Gini Index - Life expectancy years 64 UN Education Index - Poverty3 % - Urban population % 61.6 Gender equality2 - Aid per capita $ 3.9 Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report 2006 | The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2007 | OECD Development Assistance Committee 2006. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate 1990-2005. (2) Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary On 9 October 2006, in defiance of international warnings, North Korea performed an underground nuclear test. This was seen as a major blow to global efforts aimed at curbing North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, and as an emphatic statement of its determination to use every available means in order to survive. -

Everyday Life

Everyday Life The North Korean people live under a strict communist regime. They have no say in how their country is managed. The central government controls nearly every aspect of life in the country. Most jobs don’t have salaries. Food and clothing are mostly provided by the government. People who do have a job with a paycheck earn around $1,500 per year. The majority of North Korean people are very poor. They don’t have things like washing machines, fridges, or even bicycles. Practicing a religion is not allowed as the state sees it as a threat. Instead, children are raised to worship Kim Il Sung, “the President for life”. There are over 34,000 statues of Kim Il Sung in North Korea, and all wedding ceremonies must take place in front of one. Portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il can be found pretty much everywhere. All citizens must hang these portraits, which are provided by the government. Once a month, the police come over and check whether the portraits are still hanging and properly taken care of. Electricity is very unreliable in the country; most homes only have electricity a few hours per day. When buildings on one side of the street are blacked out, the other side gets electricity. When this situation occurs, there is a mad rush of children who run to their friends’ apartments on the other side. Internet is only available to the elite in North Korea. Even cellphones are extremely rare. Only people who are trusted by the government can buy a cell phone, but they must pay a registration fee of $825. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Yoon, Suk-Joon Title: Sino-South Korean relations, 1971-1990 : in the context of economic and international politics. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. SINO-SOUTH KOREAN RELATIONS. 1971-1990: IN THE CONTEXT OF ECONOWC AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS LCDR Suk-Joon Yoon A thesis submitted to the University of Bristol in fullfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Social Science, Department of Politics November 1992 7be relationship between China and South Korea during the years 1971 to 1990 is of fundamental importance to the future development of the Asian-Pacific region. -

Violence in South Korean Schools and the Relevance of Peace Education

VIOLENCE IN SOUTH KOREAN SCHOOLS AND THE RELEVANCE OF PEACE EDUCATION by SOONJUNG KWON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Education University of Birmingham March 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to explore and analyse the culture of violence which is, arguably, deeply embedded in South Korean schooling and to suggest how this can be re- directed towards a culture of peace through peace education. In order to achieve this goal, fieldwork was conducted for a year, employing critical ethnography and case studies. Data gained from this fieldwork were analysed and discussed within the conceptual frameworks of Bourdieu’s symbolic violence and peace education theories – Hick’s defining peace in particular. This finding of this thesis fall into four parts: some selected cultural elements of everyday school life; symbolized and institutionalized violence; authoritative school management and increasingly atypical employment; and how to change this culture of violence to peace: possibilities of peace education? These findings are discussed in relation to theories to show the ways in which socio-historical backgrounds and ideologies (e.g. -

Scenarios for a Transition to a Prosperous Market Economy in North Korea

Scenarios for a transition to a prosperous market economy in North Korea. Byung-Yeon Kim* and Gerard Roland** ABSTRACT: We examine in detail two possible scenarios for a transition to the market economy in North Korea. In a first scenario, we explore a path of transition of North Korea to the market economy following a regime collapse. In a second scenario, we explore a path of transition that would be chosen by the North Korean leaders, following the experience of China and Vietnam. While these scenarios have common features, they also involve important differences. Keywords: North Korea, South Korea, transition, reforms, unification, integration. JEL classification codes: P3, P31, P36, P37. * Professor of Economics at Seoul National University ** Professor of Economics and Political Science, University of California Berkeley and CEPR. 1 1. Introduction The North Korean economy has been in disastrous shape for many years causing starvation and extreme poverty. The North Korean leaders are unable to feed their people and have been shamelessly using the threat of nuclear weapons to ransom the outside world to extract food imports to keep their despotic regime alive. The death of Kim Jong-Il and accession of inexperienced son Kim Jong-Un to power raises new possibilities of big changes in North Korea. Given the inexperience of the new leader, a collapse scenario becomes more likely. Fights within the leadership might lead to chaos and a power vacuum. This is a dangerous scenario but one that is needed to be prepared for. International cooperation will be required to organize emergency aid (food, medicine, basic order) fast and efficiently and avoid mass migration. -

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953

The Causes of the Korean War, 1950-1953 Ohn Chang-Il Korea Military Academy ABSTRACT The causes of the Korean War (1950-1953) can be examined in two categories, ideological and political. Ideologically, the communist side, including the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea, desired to secure the Korean peninsula and incorporate it in a communist bloc. Politically, the Soviet Union considered the Korean peninsula in the light of Poland in Eastern Europe—as a springboard to attack Russia—and asserted that the Korean government should be “loyal” to the Soviet Union. Because of this policy and strategic posture, the Soviet military government in North Korea (1945-48) rejected any idea of establishing one Korean government under the guidance of the United Nations. The two Korean governments, instead of one, were thus established, one in South Korea under the blessing of the United Nations and the other in the north under the direction of the Soviet Union. Observing this Soviet posture on the Korean peninsula, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung asked for Soviet support to arm North Korean forces and Stalin fully supported Kim and secured newly-born Communist China’s support for the cause. Judging that it needed a buffer zone against the West and Soviet aid for nation building, the Chinese government readily accepted a role to aid North Korea, specifically, in case of full American intervention in the projected war. With full support from the Soviet Union and comradely assistance from China, Kim Il-sung attacked South Korea with forces that were better armed, equipped, and prepared than their counterparts in South Korea. -

Gendered Rhetoric in North Korea's International

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Gendered rhetoric in North Korea’s international relations (1946–2011) Amanda Kelly Anderson University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Anderson, Amanda Kelly, Gendered rhetoric in North Korea’s international relations (1946–2011), Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, 2015. -

Documentary Kim Jong Il

For North Koreans who remain in the camps The cult of personality surrounding the Kim family began with the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung, who was depicted in government propaganda as a loving father to his people. Although his leadership was brutal, his death in 1994 was deeply mourned. (Photo of painting by Blaine Harden) ‘There is no “human rights issue” in this country, as everyone leads the most dignified and happy life.’ [North] Korean Central News Agency, 6 March 2009 Preface His first memory is an execution. He walked with his mother to a wheat field near the Taedong River, where guards had rounded up several thousand prisoners. Excited by the crowd, the boy crawled between adult legs to the front row, where he saw guards tying a man to a wooden pole. Shin In Geun was four years old, too young to understand the speech that came before that killing. At dozens of executions in years to come, he would listen to a supervising guard telling the crowd that the prisoner about to die had been offered ‘redemption’ through hard labour, but had rejected the generosity of the North Korean government. To prevent the prisoner from cursing the state that was about to take his life, guards stuffed pebbles into his mouth then covered his head with a hood. At that first execution, Shin watched three guards take aim. Each fired three times. The reports of their rifles terrified the boy and he fell over backwards. But he scrambled to his feet in time to see guards untie a slack, blood-spattered body, wrap it in a blanket and heave it into a cart.