Confidence And/Or Control? Seeking a New Relationship Between North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’S Corporate World

Ranks & Files: Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’s Corporate World by Michael Morgan Prentice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Matthew Hull, Chair Associate Professor Juhn Young Ahn Professor Gerald F. Davis Associate Professor Michael Paul Lempert Professor Barbra A. Meek Professor Erik A. Mueggler Michael Morgan Prentice [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-2981-7850 © Michael Morgan Prentice 2017 Acknowledgments A doctoral program is inexorably linked to the document – this one – that summarizes the education, research, and development of a student and their ideas over the course of many years. The single authorship of such documents is often an aftereffect only once a text is completed. Indeed, while I have written all the words on these pages and am responsible for them, the influences behind the words extend to many people and places over the course of many years whose myriad contributions must be mentioned. This dissertation project has been generously funded at various stages. Prefield work research and coursework were funded through summer and academic year FLAS Grants from the University of Michigan, a Korea Foundation pre-doctoral fellowship, and a SeAH-Haiam Arts & Sciences summer fellowship. Research in South Korea was aided by a Korea Foundation Language Grant, a Fulbright-IIE Research grant, a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, and a Rackham Centennial Award. The dissertation writing stage was supported by the Rackham Humanities fellowship, a Social Sciences Research Council Korean Studies Dissertation Workshop, and the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-OLU-2240001). -

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea's Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Jeongmuk Kang Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 30 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2012. E, 30 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Supervisor: Gloria Gallardo Evaluator: Anders Larsson Contents List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ iii Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. -

HRNK, NYU School of Law, the Hurford Foundation, CFR's Winston

20th Annual Timothy A. Gelatt Dialogue on the Rule of Law in East Asia International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN Tuesday, November 11, 2014 1:30–7:00 p.m. Greenberg Lounge 40 Washington Square South NYU School of Law International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN 1:30 p.m. Welcome Jerome Cohen, Professor and Co-Director, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law; Adjunct Senior Fellow for Asia, Council on Foreign Relations Greg Scarlatoiu, Executive Director, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1:40 p.m. The Current Context Keynote: An Overview: The DPRK and the World Stephen Bosworth, Senior Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Chairman, US-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University; Former US Ambassador to South Korea, US Special Repre- sentative for North Korea Policy; Dean, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University Comment: Are We Prisoners of Korean History? Charles Armstrong, Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies in the Social Sciences, Columbia University Discussion Moderator: Dr. Myung-Soo Lee, Senior Research Scholar, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law 2:30 p.m. The Refugee Problem, International Law and China’s Role My Struggles as a Defector in North Korea, China and South Korea Hyeonseo Lee, Refugee Activist China’s Forced Repatriation of North Korean Refugees and International Law Roberta Cohen, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution; Co-Chair, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Rescuing North Korean Refugees: The Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Melanie Kirkpatrick, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute; author of Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Discussion Moderator: Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law; Faculty Director and Co-Chair, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, NYU School of Law 3:45 p.m. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Yoon, Suk-Joon Title: Sino-South Korean relations, 1971-1990 : in the context of economic and international politics. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. SINO-SOUTH KOREAN RELATIONS. 1971-1990: IN THE CONTEXT OF ECONOWC AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS LCDR Suk-Joon Yoon A thesis submitted to the University of Bristol in fullfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Social Science, Department of Politics November 1992 7be relationship between China and South Korea during the years 1971 to 1990 is of fundamental importance to the future development of the Asian-Pacific region. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles an International College In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Stephanie Kim 2014 © Copyright by Stephanie Kim 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education by Stephanie Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Val D. Rust, Chair Under the slogan of internationalization, Korean universities have opened international colleges that promise an educational experience on par with elite universities anywhere in the world. These colleges conduct their classes in English and hire Western faculty members as a way to create campus settings that better attract and accommodate foreign students. What is the meaning of “international” in this context? Based on 12 months of fieldwork, my dissertation offers an ethnographic study of an international college in South Korea to uncover underlying assumptions and meanings in the internationalization of higher education. By using an international college as a point of entry, I argue that internationalization reforms equate to the adoption of Anglo-Saxon academic paradigms by which Korean universities have been modeled after in the internationalization of higher education more broadly. With international colleges in particular, the kinds of research activities that count as ii international are not just being adopted, but the knowledge workers themselves—“imported” faculty members from the United States and Western Europe—are brought into a Korean university setting as a way to attract as many foreign students as possible. -

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-Making Under Kim Jong-Un a Second Year Assessment

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-making under Kim Jong-un A Second Year Assessment Ken E. Gause Cleared for public release COP-2014-U-006988-Final March 2014 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the glob- al community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob- lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow- ing areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Air War Korea, 1950-53

This extensive chronology recalls key events in the first war fought by the independent US Air Force. Air War Korea, 1950–53 1950 o commemorate the Korean War, the US June 25: North Korea invaded South Korea. Simultaneously, North Korean troops made an amphibious landing at Kangnung Air Force Historian commissioned Air on the east coast just south of the 38th parallel. North Korean Force Historical Research Agency to com- fighter aircraft attacked airfields at Kimpo and Seoul, the South T Korean capital, destroying one USAF C-54 on the ground at pile a chronology of significant events in USAF’s Kimpo. operations. The result was “The US Air Force’s John J. Muccio, US ambassador to South Korea, relayed to President Harry S. Truman a South Korean request for US air First War: Korea 1950–1953,” edited by A. Timothy assistance and ammunition. The UN Security Council unani- Warnock. What follows is a condensed version. mously called for a cease-fire and withdrawal of the North Korean Army to north of the 38th parallel. The resolution asked all UN members to support the withdrawal of the NKA and to render no assistance to North Korea. Note: Each entry uses the local date, which, in Two 7th Fighter–Bomber Squadron F-84s, laden with Maj. Gen. Earle E. Partridge, who was commander, 5th Air bombs and fuel, just clear the end of the runway at Taegu at theater, was one day later than in the US. Dates Force, but serving as acting commander of Far East Air Forces (FEAF), ordered wing commanders to prepare for air evacuation the start of a 1952 mission. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

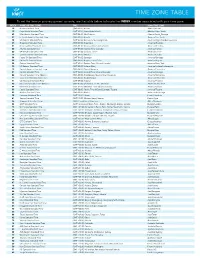

Time Zone Table

TIME ZONE TABLE To set the time on your equipment console, use the table below to locate the INDEX number associated with your time zone. INDEX NAME OF TIME ZONE TIME IANA TIME ZONE 10 Azores Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Azores Atlantic/Azores 12 Cape Verde Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Cape Verde Islands Atlantic/Cape_Verde 43 Mid-Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-02:00) Mid-Atlantic Atlantic/South_Georgia 27 E. South America Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Brasilia America/Sao_Paulo 58 SA Eastern Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Buenos Aires, Georgetown America/Argentina/Buenos_Aires 35 Greenland Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Greenland America/Godthab 51 Newfoundland Standard Time (GMT-03:30) Newfoundland and Labrador America/St_Johns 06 Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Atlantic Time (Canada) America/Halifax 60 SA Western Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Caracas, La Paz America/La_Paz 17 Central Brazilian Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Manaus America/Cuiaba 54 Pacific SA Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Santiago America/Santiago 59 SA Pacific Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Bogota, Lima, Quito America/Bogota 28 Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time (US and Canada) America/New_York 70 US Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Indiana (East) America/Indiana/Indianapolis 15 Central America Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central America America/Costa_Rica 21 Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central Time (US and Canada) America/Chicago 22 Central Standard Time (Mexico) (GMT-06:00) Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey America/Monterrey 11 Canada Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Saskatchewan -

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-Making Under Kim Jong-Un a First Year Assessment

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-making under Kim Jong-un A First Year Assessment Ken E. Gause Cleared for public release COP-2013-U-005684-Final September 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the glob- al community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob- lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow- ing areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Understanding Translanguaging and Identity Among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 2017 Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Ryoo, Nancy, "Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 412. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/412 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco UNDERSTANDING TRANSLANGUAGING AND IDENTITY AMONG KOREAN BILINGUAL ADULTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of International and Multicultural Education In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Education By Nancy Eunjoo Ryoo San Francisco, CA December 2017 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT “Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults” This qualitative study, conducted at a Northern California university, explored how six Korean bilingual adults expressed their unique identities while utilizing both Korean and English in their daily and academic lives. The six study participants shared their journeys as bilingual adults who migrated to the United States from South Korea to attend graduate school. -

Time Zone Boundaries V2016.10 Updates

Time Zone Changes applied to October 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Many areas of Russia have changed the name of their time zone to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Cyprus ▪ On October 30, 2016, when Europe and the rest of Cyprus will set their clocks back 1 hour to UTC+2, Northern Cyprus will remain on UTC+3. 1 Time Zone Changes applied to April 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Magdan Oblast will forward 1 hour April 24, 2016. Venezuela ▪ On May 1, Venezuelans will set their clocks forward 30 minutes. Azerbaijan ▪ Azerbaijan has cancelled Daylight Saving Time (DST) and will not move the clocks forward on March 27, 2016. 2 Time Zone Changes applied to March 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ President Putin signed four bills into law, making changes to the following time zone regions: Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic and Altai Krai. The result of these changes modify/create the time zone regions of Transbaikal (Zabaykalsky Krai), Astrakhan Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic, and Altai Krai. Chile ▪ Chile will resume seasonal clock changes in 2016 after spending all of last year on Daylight Saving Time (DST). The South American country will turn clocks back by one hour in May. Brazil ▪ Residents Clocks in southern Brazilian states will be turned back by 1 hour at midnight between Saturday, February 20 and Sunday, February 21, 2016, as Daylight Saving Time (DST) ends. Haiti ▪ Haiti will not observe Daylight Saving Time (DST) in 2016. The planned clock change on Sunday, March 13, 2016 has just been canceled. United States ▪ Metlakatla, Alaska will observe the same local time as the rest of the state from now on.