Jeong and Korean Immigration Into North Carolina By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confidence And/Or Control? Seeking a New Relationship Between North

Hans-Joachim Schmidt Confidence and/or Control? Seeking a new relationship between North and South Korea PRIF Reports No. 62 ã Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2002 Correspondence to: HSFK Leimenrode 29 60322 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49 (0)69/95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69/55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:/www.hsfk.de Translation: Katharine Hughes MA, Oxford ISBN: 3-933293-64-2 € 10,– Summary The final curtain has not yet fallen on the East-West conflict in the Korean peninsula. The heavily armed forces of North and South Korea are still at a stand-off, with almost two million soldiers, supported by 37,000 US troops on the South Korean side. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, which led to the partition of Korea, both countries find themselves technically still at war. So far, there has merely been a cease-fire in force. While South Korea has since developed into a stable democracy and one of the most economically advanced nations in Asia, the Stalinist rule in the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) is threatening to disintegrate. The economic situation there deteriorated drastically during the 1990s due to economic mismanagement and a number of natural disasters. Despite this worsening economic plight, North Korea possesses the world’s fifth largest army, with almost 1.2 million soldiers, and spends 25-33 % of its GNP on military defence (South Korea spends approx. 3 %). This fuels the fear that the Communist regime in the DPRK could very soon collapse. -

Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’S Corporate World

Ranks & Files: Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’s Corporate World by Michael Morgan Prentice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Matthew Hull, Chair Associate Professor Juhn Young Ahn Professor Gerald F. Davis Associate Professor Michael Paul Lempert Professor Barbra A. Meek Professor Erik A. Mueggler Michael Morgan Prentice [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-2981-7850 © Michael Morgan Prentice 2017 Acknowledgments A doctoral program is inexorably linked to the document – this one – that summarizes the education, research, and development of a student and their ideas over the course of many years. The single authorship of such documents is often an aftereffect only once a text is completed. Indeed, while I have written all the words on these pages and am responsible for them, the influences behind the words extend to many people and places over the course of many years whose myriad contributions must be mentioned. This dissertation project has been generously funded at various stages. Prefield work research and coursework were funded through summer and academic year FLAS Grants from the University of Michigan, a Korea Foundation pre-doctoral fellowship, and a SeAH-Haiam Arts & Sciences summer fellowship. Research in South Korea was aided by a Korea Foundation Language Grant, a Fulbright-IIE Research grant, a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, and a Rackham Centennial Award. The dissertation writing stage was supported by the Rackham Humanities fellowship, a Social Sciences Research Council Korean Studies Dissertation Workshop, and the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-OLU-2240001). -

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea's Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Jeongmuk Kang Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 30 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2012. E, 30 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Supervisor: Gloria Gallardo Evaluator: Anders Larsson Contents List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ iii Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. -

HRNK, NYU School of Law, the Hurford Foundation, CFR's Winston

20th Annual Timothy A. Gelatt Dialogue on the Rule of Law in East Asia International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN Tuesday, November 11, 2014 1:30–7:00 p.m. Greenberg Lounge 40 Washington Square South NYU School of Law International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN 1:30 p.m. Welcome Jerome Cohen, Professor and Co-Director, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law; Adjunct Senior Fellow for Asia, Council on Foreign Relations Greg Scarlatoiu, Executive Director, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1:40 p.m. The Current Context Keynote: An Overview: The DPRK and the World Stephen Bosworth, Senior Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Chairman, US-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University; Former US Ambassador to South Korea, US Special Repre- sentative for North Korea Policy; Dean, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University Comment: Are We Prisoners of Korean History? Charles Armstrong, Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies in the Social Sciences, Columbia University Discussion Moderator: Dr. Myung-Soo Lee, Senior Research Scholar, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law 2:30 p.m. The Refugee Problem, International Law and China’s Role My Struggles as a Defector in North Korea, China and South Korea Hyeonseo Lee, Refugee Activist China’s Forced Repatriation of North Korean Refugees and International Law Roberta Cohen, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution; Co-Chair, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Rescuing North Korean Refugees: The Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Melanie Kirkpatrick, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute; author of Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Discussion Moderator: Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law; Faculty Director and Co-Chair, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, NYU School of Law 3:45 p.m. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles an International College In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Stephanie Kim 2014 © Copyright by Stephanie Kim 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education by Stephanie Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Val D. Rust, Chair Under the slogan of internationalization, Korean universities have opened international colleges that promise an educational experience on par with elite universities anywhere in the world. These colleges conduct their classes in English and hire Western faculty members as a way to create campus settings that better attract and accommodate foreign students. What is the meaning of “international” in this context? Based on 12 months of fieldwork, my dissertation offers an ethnographic study of an international college in South Korea to uncover underlying assumptions and meanings in the internationalization of higher education. By using an international college as a point of entry, I argue that internationalization reforms equate to the adoption of Anglo-Saxon academic paradigms by which Korean universities have been modeled after in the internationalization of higher education more broadly. With international colleges in particular, the kinds of research activities that count as ii international are not just being adopted, but the knowledge workers themselves—“imported” faculty members from the United States and Western Europe—are brought into a Korean university setting as a way to attract as many foreign students as possible. -

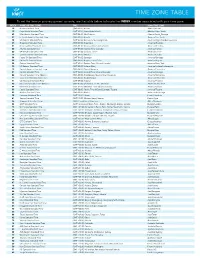

Time Zone Table

TIME ZONE TABLE To set the time on your equipment console, use the table below to locate the INDEX number associated with your time zone. INDEX NAME OF TIME ZONE TIME IANA TIME ZONE 10 Azores Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Azores Atlantic/Azores 12 Cape Verde Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Cape Verde Islands Atlantic/Cape_Verde 43 Mid-Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-02:00) Mid-Atlantic Atlantic/South_Georgia 27 E. South America Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Brasilia America/Sao_Paulo 58 SA Eastern Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Buenos Aires, Georgetown America/Argentina/Buenos_Aires 35 Greenland Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Greenland America/Godthab 51 Newfoundland Standard Time (GMT-03:30) Newfoundland and Labrador America/St_Johns 06 Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Atlantic Time (Canada) America/Halifax 60 SA Western Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Caracas, La Paz America/La_Paz 17 Central Brazilian Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Manaus America/Cuiaba 54 Pacific SA Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Santiago America/Santiago 59 SA Pacific Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Bogota, Lima, Quito America/Bogota 28 Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time (US and Canada) America/New_York 70 US Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Indiana (East) America/Indiana/Indianapolis 15 Central America Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central America America/Costa_Rica 21 Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central Time (US and Canada) America/Chicago 22 Central Standard Time (Mexico) (GMT-06:00) Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey America/Monterrey 11 Canada Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Saskatchewan -

Understanding Translanguaging and Identity Among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 2017 Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Ryoo, Nancy, "Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 412. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/412 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco UNDERSTANDING TRANSLANGUAGING AND IDENTITY AMONG KOREAN BILINGUAL ADULTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of International and Multicultural Education In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Education By Nancy Eunjoo Ryoo San Francisco, CA December 2017 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT “Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults” This qualitative study, conducted at a Northern California university, explored how six Korean bilingual adults expressed their unique identities while utilizing both Korean and English in their daily and academic lives. The six study participants shared their journeys as bilingual adults who migrated to the United States from South Korea to attend graduate school. -

Time Zone Boundaries V2016.10 Updates

Time Zone Changes applied to October 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Many areas of Russia have changed the name of their time zone to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Cyprus ▪ On October 30, 2016, when Europe and the rest of Cyprus will set their clocks back 1 hour to UTC+2, Northern Cyprus will remain on UTC+3. 1 Time Zone Changes applied to April 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Magdan Oblast will forward 1 hour April 24, 2016. Venezuela ▪ On May 1, Venezuelans will set their clocks forward 30 minutes. Azerbaijan ▪ Azerbaijan has cancelled Daylight Saving Time (DST) and will not move the clocks forward on March 27, 2016. 2 Time Zone Changes applied to March 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ President Putin signed four bills into law, making changes to the following time zone regions: Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic and Altai Krai. The result of these changes modify/create the time zone regions of Transbaikal (Zabaykalsky Krai), Astrakhan Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic, and Altai Krai. Chile ▪ Chile will resume seasonal clock changes in 2016 after spending all of last year on Daylight Saving Time (DST). The South American country will turn clocks back by one hour in May. Brazil ▪ Residents Clocks in southern Brazilian states will be turned back by 1 hour at midnight between Saturday, February 20 and Sunday, February 21, 2016, as Daylight Saving Time (DST) ends. Haiti ▪ Haiti will not observe Daylight Saving Time (DST) in 2016. The planned clock change on Sunday, March 13, 2016 has just been canceled. United States ▪ Metlakatla, Alaska will observe the same local time as the rest of the state from now on. -

Science-Fictional Imaginaries and the Technik of Writing in Contemporary Korea

Techno-Fiction: Science-Fictional Imaginaries and the Technik of Writing in Contemporary Korea Dahye Kim Department of East Asian Studies McGill University, Montreal May 2020 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright @ 2020 Kim, Dahye All rights reserved CONTENTS ABSTRACT English ......................................................................................................................................... i French ........................................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ iii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 ................................................................................................................................ 32 Techno-Fiction and the Cultural Techniques of Early Science-Fiction Fans in South Korea CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................................................................ 70 Pok Kŏ-il and the Hangul Typewriter: Failing Communication and the Korean Writing System CHAPTER 3 .............................................................................................................................. 108 The Interface of Hangul and Technological -

Confidence And/Or Control?

Hans-Joachim Schmidt Confidence and/or Control? Seeking a new relationship between North and South Korea PRIF Reports No. 62 ã Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2002 Correspondence to: HSFK Leimenrode 29 60322 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49 (0)69/95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69/55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:/www.hsfk.de Translation: Katharine Hughes MA, Oxford ISBN: 3-933293-64-2 € 10,– Summary The final curtain has not yet fallen on the East-West conflict in the Korean peninsula. The heavily armed forces of North and South Korea are still at a stand-off, with almost two million soldiers, supported by 37,000 US troops on the South Korean side. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, which led to the partition of Korea, both countries find themselves technically still at war. So far, there has merely been a cease-fire in force. While South Korea has since developed into a stable democracy and one of the most economically advanced nations in Asia, the Stalinist rule in the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) is threatening to disintegrate. The economic situation there deteriorated drastically during the 1990s due to economic mismanagement and a number of natural disasters. Despite this worsening economic plight, North Korea possesses the world’s fifth largest army, with almost 1.2 million soldiers, and spends 25-33 % of its GNP on military defence (South Korea spends approx. 3 %). This fuels the fear that the Communist regime in the DPRK could very soon collapse. -

Cultural Identity and Cultural Policy in South Korea

The International Journal of Cultural Policy, 2002 Vol. 8 (1), pp. 37–48 CULTURAL IDENTITY AND CULTURAL POLICY IN SOUTH KOREA Haksoon Yim* Korea Culture and Contents Agency, Seoul, South Korea INTRODUCTION With the evolution of cultural policy in South Korea, there has been an associated change in cultural policy objectives, these being primarily concerned with establishing cultural identity, the development of culture and the arts, the promotion of the quality of cultural life and the fostering of cultural industries. However, as a whole, since the establishment of the first republic of 1948, the foremost challenge of Korean cultural policy has been to resolve the issue of cultural identity. As Yersu Kim (1976, 10–12) observes, until the late 1970s, the construction of cultural identity provided perhaps the most significant rationale for cultural policy. With regard to this characteristic of Korean cultural policy, it is instructive to identify why the issue of cultural identity has been considered important, and furthermore, to what extent this issue has actually affected cultural policy. This article, then is concerned with the relationship between cultural identity and cultural policy. Indeed, within many countries, the issue of cultural identity has been considered as a cultural policy objective (Council of Europe, 1997, 45–46; Bradley, 1998, 351–367; Burgi- Golub, 2000, 211–223). Issues of multiculturalism, cultural diversity and cultural globalization are all closely bound up with the issue of cultural identity (Jong, 1998, 357–387; Held et al., 1999, 328–375; Tomlinson, 1999; Bauer, 2000, 77–95). However, the characteristics and causes of the issue of cultural identity vary, depending on the characteristics of the countries in which cultural identity is formulated and transformed. -

An Analysis of Democratic Consolidation in South Korea

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1996 An Analysis of Democratic Consolidation in South Korea Sangmook Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Sangmook, "An Analysis of Democratic Consolidation in South Korea" (1996). Master's Theses. 5013. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/5013 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION INSOUTH KOREA by Sangmook Lee A Thesis Submitted to the· Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1996 Copyright by Sangmook Lee 1996 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people have provided crucialsupport along the way. Special thanks goes to my committee chair, Dr. Lawrence Ziring, for his encouragement, guidance, and suggestions throughout this study. I also thank the members of my committee, Dr. Alan C. Isaak and Dr. Peter Kobrak, who read this draft very carefully and made numerous comments which greatly improved the quality of my thesis. This paper is dedicated to my family without whom it could hardly have been completed. I should like to thank my parents, my father, Byungkee Lee, and my mother, SuknamLee, who provided much support and encouragement throughout my graduate career.