IRM): South Korea Progress Report 2016–2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A PARTNER for CHANGE the Asia Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 a PARTNER Characterizing 60 Years of Continuous Operations of Any Organization Is an Ambitious Task

SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION IN KOREA SIX DECADES OF THE ASIA FOUNDATION A PARTNER FOR CHANGE A PARTNER The AsiA Foundation in Korea 1954-2017 A PARTNER Characterizing 60 years of continuous operations of any organization is an ambitious task. Attempting to do so in a nation that has witnessed fundamental and dynamic change is even more challenging. The Asia Foundation is unique among FOR foreign private organizations in Korea in that it has maintained a presence here for more than 60 years, and, throughout, has responded to the tumultuous and vibrant times by adapting to Korea’s own transformation. The achievement of this balance, CHANGE adapting to changing needs and assisting in the preservation of Korean identity while simultaneously responding to regional and global trends, has made The Asia Foundation’s work in SIX DECADES of Korea singular. The AsiA Foundation David Steinberg, Korea Representative 1963-68, 1994-98 in Korea www.asiafoundation.org 서적-표지.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:42 서적152X225-2.indd 4 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 A PARTNER FOR CHANGE Six Decades of The Asia Foundation in Korea 1954–2017 Written by Cho Tong-jae Park Tae-jin Edward Reed Edited by Meredith Sumpter John Rieger © 2017 by The Asia Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission by The Asia Foundation. 서적152X225-2.indd 1 17. 6. 8. 오전 10:37 서적152X225-2.indd 2 17. -

Confidence And/Or Control? Seeking a New Relationship Between North

Hans-Joachim Schmidt Confidence and/or Control? Seeking a new relationship between North and South Korea PRIF Reports No. 62 ã Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2002 Correspondence to: HSFK Leimenrode 29 60322 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49 (0)69/95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69/55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:/www.hsfk.de Translation: Katharine Hughes MA, Oxford ISBN: 3-933293-64-2 € 10,– Summary The final curtain has not yet fallen on the East-West conflict in the Korean peninsula. The heavily armed forces of North and South Korea are still at a stand-off, with almost two million soldiers, supported by 37,000 US troops on the South Korean side. Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, which led to the partition of Korea, both countries find themselves technically still at war. So far, there has merely been a cease-fire in force. While South Korea has since developed into a stable democracy and one of the most economically advanced nations in Asia, the Stalinist rule in the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) is threatening to disintegrate. The economic situation there deteriorated drastically during the 1990s due to economic mismanagement and a number of natural disasters. Despite this worsening economic plight, North Korea possesses the world’s fifth largest army, with almost 1.2 million soldiers, and spends 25-33 % of its GNP on military defence (South Korea spends approx. 3 %). This fuels the fear that the Communist regime in the DPRK could very soon collapse. -

Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’S Corporate World

Ranks & Files: Corporate Hierarchies, Genres of Management, and Shifting Control in South Korea’s Corporate World by Michael Morgan Prentice A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Matthew Hull, Chair Associate Professor Juhn Young Ahn Professor Gerald F. Davis Associate Professor Michael Paul Lempert Professor Barbra A. Meek Professor Erik A. Mueggler Michael Morgan Prentice [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-2981-7850 © Michael Morgan Prentice 2017 Acknowledgments A doctoral program is inexorably linked to the document – this one – that summarizes the education, research, and development of a student and their ideas over the course of many years. The single authorship of such documents is often an aftereffect only once a text is completed. Indeed, while I have written all the words on these pages and am responsible for them, the influences behind the words extend to many people and places over the course of many years whose myriad contributions must be mentioned. This dissertation project has been generously funded at various stages. Prefield work research and coursework were funded through summer and academic year FLAS Grants from the University of Michigan, a Korea Foundation pre-doctoral fellowship, and a SeAH-Haiam Arts & Sciences summer fellowship. Research in South Korea was aided by a Korea Foundation Language Grant, a Fulbright-IIE Research grant, a Wenner-Gren Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, and a Rackham Centennial Award. The dissertation writing stage was supported by the Rackham Humanities fellowship, a Social Sciences Research Council Korean Studies Dissertation Workshop, and the Core University Program for Korean Studies through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and Korean Studies Promotion Service of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2016-OLU-2240001). -

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea's Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation

A Study on the Future Sustainability of Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Jeongmuk Kang Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Uppsala University, Department of Earth Sciences Master Thesis E, in Sustainable Development, 30 credits Printed at Department of Earth Sciences, Master’s Thesis Geotryckeriet, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 2012. E, 30 credits Examensarbete i Hållbar Utveckling 93 A Study on the Future Sustainability of Sejong, South Korea’s Multifunctional Administrative City, Focusing on Implementation of Transit Oriented Development Jeongmuk Kang Supervisor: Gloria Gallardo Evaluator: Anders Larsson Contents List of Tables ......................................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................ iii Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. -

HRNK, NYU School of Law, the Hurford Foundation, CFR's Winston

20th Annual Timothy A. Gelatt Dialogue on the Rule of Law in East Asia International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN Tuesday, November 11, 2014 1:30–7:00 p.m. Greenberg Lounge 40 Washington Square South NYU School of Law International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN 1:30 p.m. Welcome Jerome Cohen, Professor and Co-Director, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law; Adjunct Senior Fellow for Asia, Council on Foreign Relations Greg Scarlatoiu, Executive Director, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1:40 p.m. The Current Context Keynote: An Overview: The DPRK and the World Stephen Bosworth, Senior Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Chairman, US-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University; Former US Ambassador to South Korea, US Special Repre- sentative for North Korea Policy; Dean, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University Comment: Are We Prisoners of Korean History? Charles Armstrong, Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies in the Social Sciences, Columbia University Discussion Moderator: Dr. Myung-Soo Lee, Senior Research Scholar, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law 2:30 p.m. The Refugee Problem, International Law and China’s Role My Struggles as a Defector in North Korea, China and South Korea Hyeonseo Lee, Refugee Activist China’s Forced Repatriation of North Korean Refugees and International Law Roberta Cohen, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution; Co-Chair, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Rescuing North Korean Refugees: The Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Melanie Kirkpatrick, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute; author of Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Discussion Moderator: Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law; Faculty Director and Co-Chair, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, NYU School of Law 3:45 p.m. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles an International College In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Stephanie Kim 2014 © Copyright by Stephanie Kim 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An International College in South Korea as a Third Space between Korean and US Models of Higher Education by Stephanie Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Val D. Rust, Chair Under the slogan of internationalization, Korean universities have opened international colleges that promise an educational experience on par with elite universities anywhere in the world. These colleges conduct their classes in English and hire Western faculty members as a way to create campus settings that better attract and accommodate foreign students. What is the meaning of “international” in this context? Based on 12 months of fieldwork, my dissertation offers an ethnographic study of an international college in South Korea to uncover underlying assumptions and meanings in the internationalization of higher education. By using an international college as a point of entry, I argue that internationalization reforms equate to the adoption of Anglo-Saxon academic paradigms by which Korean universities have been modeled after in the internationalization of higher education more broadly. With international colleges in particular, the kinds of research activities that count as ii international are not just being adopted, but the knowledge workers themselves—“imported” faculty members from the United States and Western Europe—are brought into a Korean university setting as a way to attract as many foreign students as possible. -

ICDMFR 2021 COVID-19 Response Guideline

CONTENTS Welcome Message 01 Organizing Committee 02 Program at a Glance 03 Floor Plan 04 Congress Information 05 • Congress Overview • Registration • Wi-Fi / Internet Lounge • Transportation • Virtual Website Speakers 08 • Keynote Lecture • Special Lecture • Invited Session • 대한영상치의학회 오픈세션 (Session in Korean) Scientific Program 11 • Day 1 – April 28 (Wed) • Day 2 – April 29 (Thu) • Day 3 – April 30 (Fri) • Day 4 – May 1 (Sat) • Oral Presentation • e-Poster Presentation Sponsors & Exhibitors 27 ICDMFR 2021 COVID-19 Response Guideline 37 Welcome Message Dear participants of ICDMFR 2021, On behalf of the Organizing Committee of the 23rd International Congress of Dento- MaxilloFacial Radiology (ICDMFR 2021), it is my great pleasure to welcome you to the ICDMFR 2021 to be held from April 28 to May 1, 2021, under the theme of “Reading and Leading Dentistry.” It is the second ICDMFR to be held in South Korea 27 years after the 10th ICDMFR (President: Prof. Dong-Soo You) was held in 1994 in Seoul. What is very regrettable is that Professor You passed away in January this year so we will miss his presence at this Congress. As we all know, the world has faced unexpected challenges due to the ongoing spread of COVID-19. The global epidemic and community infections have not yet come to an end. As a result, we decided to hold ICDMFR 2021 in the format of a hy- brid meeting where Korean participants will attend in-person/on-site (Kimdaejung Convention Center in Gwangju, South Korea), while the overseas participants will join the meeting online and participate in real-time discussions. -

PLATELET-001 All Participating Site IRB/EC List Ver.1.0 07May2020 Confidential

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Yonsei University College of Medicine Gangnam Severance Hospital PLATELET-001_All Participating Site IRB/EC List_Ver.1.0_07May2020 Confidential PLATELET-001 Site Institutional Review Board(IRB) / Site Name Address No. Ethic Committee(EC) Yonsei University College of Medicine Gangnam Severance Yonsei University College of Medicine Yonsei University Gangnam Severance Hospital 01 Hospital, 211, Eonju-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea, Gangnam Severance Hospital Institutional Review Board 06273 Gachon University Gil Medical Center Gachon University Gil Medical Center, 21, Namdong-daero 02 Gachon University Gil Medical Center Institutional Review Board 774beon-gil, Namdong-gu, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 21565 Catholic Kwandong University Catholic Kwandong University International 25, Simgok-ro 100beon-gil, Seo-gu, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 03 International St.Mary`s Hospital St.Mary`s Hospital Institutional Review Board 22711 KyungHee University Hospital Kyung Hee University Korean Medicine Hospital Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong, 892, Dongnam-ro, 04 at Gangdong at Gangdong Institutional Review Board Gangdong-gu, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 05278 Kangwon National University Hospital Kangwan National University Hospital, 156, Baengnyeong-ro, 05 Kangwan National University Hospital Institutional Review Board Chuncheon-si, -

Appreciations to Peer Reviewers for Journal of Korean Medical Science 2017

J Korean Med Sci. 2018 Mar 26;33(13):e114 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e114 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Editorial Appreciations to Peer Reviewers for Journal of Korean Medical Science 2017 Sung-Tae Hong , Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Korean Medical Science Department of Parasitology and Tropical Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: Mar 21, 2018 The Journal of Korean Medical Science (JKMS) changed its online submission system to the Editorial Accepted: Mar 21, 2018 Manager® powered by the Aries Systems from 1 October 2017. In 2017, the submissions through Address for Correspondence: the old system were 910 and the new system were 227, total 1,137. A total of 320 (28.1%) of them Sung-Tae Hong, MD, PhD were overseas submissions. Overall accept rate was 27.8% in 2017. All of the submissions were Department of Parasitology and Tropical previewed and about half of them were requested to peer review. A total of 1,232 reviewers were Medicine, Seoul National University College of invited and 544 of them finished reviews. They were scored from 1 to 5 (5 is the best) for their Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, review activities. Seoul 03080, Korea. E-mail: [email protected] The JKMS sincerely appreciates contributions of peer reviewers who critically reviewed and © 2018 The Korean Academy of Medical sent us their constructive comments. Thanks to their academic contributions, JKMS can Sciences. publish quality articles and invite global readers. We expect continuous good reviews that can This is an Open Access article distributed make JKMS more academic credits. -

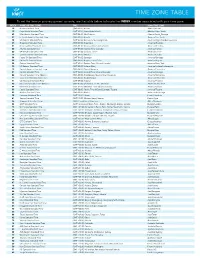

Time Zone Table

TIME ZONE TABLE To set the time on your equipment console, use the table below to locate the INDEX number associated with your time zone. INDEX NAME OF TIME ZONE TIME IANA TIME ZONE 10 Azores Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Azores Atlantic/Azores 12 Cape Verde Standard Time (GMT-01:00) Cape Verde Islands Atlantic/Cape_Verde 43 Mid-Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-02:00) Mid-Atlantic Atlantic/South_Georgia 27 E. South America Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Brasilia America/Sao_Paulo 58 SA Eastern Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Buenos Aires, Georgetown America/Argentina/Buenos_Aires 35 Greenland Standard Time (GMT-03:00) Greenland America/Godthab 51 Newfoundland Standard Time (GMT-03:30) Newfoundland and Labrador America/St_Johns 06 Atlantic Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Atlantic Time (Canada) America/Halifax 60 SA Western Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Caracas, La Paz America/La_Paz 17 Central Brazilian Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Manaus America/Cuiaba 54 Pacific SA Standard Time (GMT-04:00) Santiago America/Santiago 59 SA Pacific Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Bogota, Lima, Quito America/Bogota 28 Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Eastern Time (US and Canada) America/New_York 70 US Eastern Standard Time (GMT-05:00) Indiana (East) America/Indiana/Indianapolis 15 Central America Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central America America/Costa_Rica 21 Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Central Time (US and Canada) America/Chicago 22 Central Standard Time (Mexico) (GMT-06:00) Guadalajara, Mexico City, Monterrey America/Monterrey 11 Canada Central Standard Time (GMT-06:00) Saskatchewan -

Understanding Translanguaging and Identity Among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 2017 Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults Nancy Ryoo University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Ryoo, Nancy, "Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 412. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/412 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco UNDERSTANDING TRANSLANGUAGING AND IDENTITY AMONG KOREAN BILINGUAL ADULTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of International and Multicultural Education In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree Doctor of Education By Nancy Eunjoo Ryoo San Francisco, CA December 2017 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT “Understanding Translanguaging and Identity among Korean Bilingual Adults” This qualitative study, conducted at a Northern California university, explored how six Korean bilingual adults expressed their unique identities while utilizing both Korean and English in their daily and academic lives. The six study participants shared their journeys as bilingual adults who migrated to the United States from South Korea to attend graduate school. -

Time Zone Boundaries V2016.10 Updates

Time Zone Changes applied to October 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Many areas of Russia have changed the name of their time zone to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Cyprus ▪ On October 30, 2016, when Europe and the rest of Cyprus will set their clocks back 1 hour to UTC+2, Northern Cyprus will remain on UTC+3. 1 Time Zone Changes applied to April 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ Magdan Oblast will forward 1 hour April 24, 2016. Venezuela ▪ On May 1, Venezuelans will set their clocks forward 30 minutes. Azerbaijan ▪ Azerbaijan has cancelled Daylight Saving Time (DST) and will not move the clocks forward on March 27, 2016. 2 Time Zone Changes applied to March 2016 Delivery Russian Federation ▪ President Putin signed four bills into law, making changes to the following time zone regions: Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic and Altai Krai. The result of these changes modify/create the time zone regions of Transbaikal (Zabaykalsky Krai), Astrakhan Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, Ulyanovsk Oblast, Altai Republic, and Altai Krai. Chile ▪ Chile will resume seasonal clock changes in 2016 after spending all of last year on Daylight Saving Time (DST). The South American country will turn clocks back by one hour in May. Brazil ▪ Residents Clocks in southern Brazilian states will be turned back by 1 hour at midnight between Saturday, February 20 and Sunday, February 21, 2016, as Daylight Saving Time (DST) ends. Haiti ▪ Haiti will not observe Daylight Saving Time (DST) in 2016. The planned clock change on Sunday, March 13, 2016 has just been canceled. United States ▪ Metlakatla, Alaska will observe the same local time as the rest of the state from now on.