Korea Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korean Criminal Law Under Controversy After Democratization 49

Korean Criminal Law under Controversy after Democratization 49 Korean Criminal Law under Controversy after Democratization Cho Kuk* This Article reviews what democratization has brought and what has remained intact in Korean criminal law, focusing on the change of three Korean criminal special acts under hot debate such as the National Security Act, the Security Surveillance Act, and the Social Protection Act after democ- ratization. Then it examines the newly surfacing issues of Korean criminal law, focusing on the moralist and male-oriented biases. Keywords: criminal law, National Security Act, Security Surveillance Act, Social Protection Act, adultery, rape, homicide of lineal ascendants 1. Introduction The nationwide June Struggle of 1987 led to the collapse of Korea’s authori- tarian regime and opened a road toward democratization.1 Under the authoritari- an regime, the Constitution’s Bill of Rights was merely nominal, and criminal law and procedure were no more than instruments for maintaining the regime and suppressing the dissidents. It was not a coincidence that the June Struggle was sparked by the death of a dissident student tortured during police interroga- * Assistant Professor of Law, Seoul National University College of Law, Korea. 1. For information regarding the June Struggle, see West, James M. & Edward J. Baker, 1991. “The 1987 Constitutional Reforms in South Korea: Electoral Processes and Judicial Independence”, in Human Rights in Korea: Historical and Policy Perspectives (Harvard University Press, 1991): 221. The Review of Korean Studies Vol. 6, No. 2 (49-65) © 2003 by The Academy of Korean Studies 50 The Review of Korean Studies tion.2 Democratization brought a significant change in the Korean criminal law and procedure.3 Criminal law was a symbol of authoritarian rule in Korea. -

| Page 90 | KAFLE-KOTESOL Conference 2014

Jean Adama Jean Adama completed his MA in TESOL from California State University, Sacramento and now teaches conversation and Business English courses at Seoul National University of Science and Technology in Seoul. He has taught in three different countries across a varied range of abilities and language skills. So-Yeon Ahn So-Yeon Ahn currently lectures at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, where she conducts several research studies having to do with culture in language learning and language teacher identity. She has research interests in language and cultural awareness, social and cultural approaches to language learning, and language ideology and identity. Eunsook Ahn Eunsook Ahn is an EFL program administrator at the Seoul National University of Science and Technology (SeoulTech) Institute for Language Education and Research (ILER) where she manages several foreign language programs (English, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean). She holds a B.A. in English Language and Literature from Kwangwoon University and is currently enrolled in the Educational Administration graduate program at Yonsei University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. Shannon Ahrndt Shannon Ahrndt is an Assistant Teaching Professor at Seoul National University, where she teaches Culture & Society, Writing, and Speaking courses. She has taught in Korea since 2005, and served as a Speaking course coordinator at SNU for two years. She received her MA in Communication from the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee. Amany Alsaedi Dr. Amany Alsaedi received her BA degree with honours in English from Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia in 2000. She received her MA degree and PhD degree in English Language Teaching from the School of Modern Languages in the University of Southampton, Southampton, UK in 2006 and 2012, respectively. -

South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation

The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation By Jisung Catherine Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Elaine Kim Fall 2013 The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation © 2013 by Jisung Catherine Kim Abstract The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation by Jisung Catherine Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair In The Intimacy of Distance, I reconceive the historical experience of capitalism’s globalization through the vantage point of South Korean cinema. According to world leaders’ discursive construction of South Korea, South Korea is a site of “progress” that proves the superiority of the free market capitalist system for “developing” the so-called “Third World.” Challenging this contention, my dissertation demonstrates how recent South Korean cinema made between 1998 and the first decade of the twenty-first century rearticulates South Korea as a site of economic disaster, ongoing historical trauma and what I call impassible “transmodernity” (compulsory capitalist restructuring alongside, and in conflict with, deep-seated tradition). Made during the first years after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the films under consideration here visualize the various dystopian social and economic changes attendant upon epidemic capitalist restructuring: social alienation, familial fragmentation, and widening economic division. -

Economic Growth 9 Inflation 9 Exchange Rates 9 External Sector 10 Forecast Summary 11 Quarterly Forecasts

South Korea - Timeline 1 May 2018 A chronology of key events: 1945 - After World War II, Japanese occupation ends with Soviet troops occupying area north of the 38th parallel, and US troops in the south. 1948 - Republic of Korea proclaimed. The Korean war (1950-1953) killed at least 2.5 million people. It pitted the North - backed by Chinese forces - against the South, supported militarily by the United Nations In Depth: The Korean War On This Day 1950: UN condemns North Korean invasion 1950 - South declares independence, sparking North Korean invasion. 1953 - Armistice ends Korean War, which has cost two million lives. 1950s - South sustained by crucial US military, economic and political support. 1960 - President Syngman Ree steps down after student protests against electoral fraud. New constitution forms Second Republic, but political freedom remains limited. Coup 1961 - Military coup puts General Park Chung-hee in power. 1963 - General Park restores some political freedom and proclaims Third Republic. Major programme of industrial development begins. 1972 - Martial law. Park increases his powers with constitutional changes. After secret North-South talks, both sides seek to develop dialogue aimed at unification. 1979 - Park assassinated. General Chun Doo-hwan seizes power the following year. Gwangju massacre 133 Hundreds died as troops fired on 1980 rally 2005: Lingering legacy of Korean massacre 1980 - Martial law declared after student demonstrations. In the city of Gwangju army kills at least 200 people. Fifth republic and new constitution. 1981 - Chun indirectly elected to a seven year term. Martial law ends, but government continues to have strong powers to prevent dissent. -

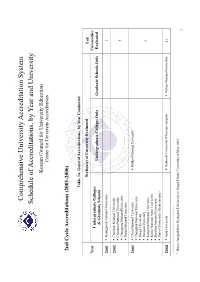

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

Opposition Landslide in Mayoral Elections Shifts Political Landscape

Opposition landslide in mayoral elections shifts political landscape 12 April 2021 Mayoral candidates from the conservative opposition People Power Party, Oh Se- hoon in Seoul and Park Hyung-joon in Busan, swept to victory on 7 April in a major upset for the ruling Democratic Party and its President, Moon Jae-in. The results show how Moon’s popularity has waned since he secured a 180-seat majority in the National Assembly elections last April. Moon’s reform agenda – to reduce the power of prosecutors and cool the property market – has encountered fierce opposition and, in the case of the property measures, backfired. The People Power Party’s twin victories highlight the level of public fatigue at the extreme confrontation between the Prosecutor's Office and the Minister of Justice, as well as disillusionment with ballooning house prices and rents, despite reforms that were supposed to provide relief to first-time buyers and tenants. Public anger against Moon’s Democratic Party was also exacerbated by land speculation by employees of the Korea Land & Housing Corporation, a public institution, based on their access to insider information about the development of a new town, an issue that was uncovered just before the election. Efforts to improve inter-Korean relations, a key focus of the Moon administration, have also fallen into stalemate, further contributing to falls in the ruling party’s popularity. While the People’s Power Party fought fiercely against Moon’s reforms, it has been criticised for failing to provide realistic policy alternatives. The party is also tainted by historic ties, not only to big business and the military, but also to the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye by the Constitutional Court in 2017 – a first in Korean history. -

Law and Society in Korea

JOBNAME: Yang PAGE: 1 SESS: 2 OUTPUT: Mon Dec 3 11:36:58 2012 Law and Society in Korea Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Yang_Law_and_Society_in_Korea / Division: 00_Prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 24/10 JOBNAME: Yang PAGE: 2 SESS: 6 OUTPUT: Mon Dec 3 11:36:58 2012 ELGAR KOREAN LAW INASSOCIATIONWITH THE LAW RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Series editor: In Seop Chung, Law Research Institute, Seoul National University, Korea In the dramatic transformation Korean society has experienced for the past 40 years, law has played a pivotal role. However, not much information about Korean law and the Korean legal system is readily available in English. The Elgar Korean Law series fills this gap by providing authoritative and in-depth knowledge on trade law and regulation, litigation, and law and society in Korea.The series will be an indispensable source of legal information and insight on Korean law for academics, students and practitioners. Titles in the series include: Litigation in Korea Edited by Kuk Cho Trade Law and Regulation in Korea Edited by Seung Wha Chang and Won-Mog Choi Korean Business Law Edited by Hwa-Jin Kim Law and Society in Korea Edited by HyunahYang Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Yang_Law_and_Society_in_Korea / Division: 00_Prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 28/11 JOBNAME: Yang PAGE: 3 SESS: 9 OUTPUT: Wed Dec 5 12:52:59 2012 Law and Society in Korea Edited by HyunahYang Professor of Law, Seoul National University, Korea ELGAR KOREAN LAW INASSOCIATIONWITH THE LAW RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Yang_Law_and_Society_in_Korea / Division: 00_Prelims /Pg. -

South Korea Report Thomas Kalinowski, Sang-Young Rhyu, Aurel Croissant (Coordinator)

South Korea Report Thomas Kalinowski, Sang-young Rhyu, Aurel Croissant (Coordinator) Sustainable Governance Indicators 2018 © vege - stock.adobe.com Sustainable Governance SGI Indicators SGI 2018 | 2 South Korea Report Executive Summary The period under review saw dramatic changes in South Korea, with the parliament voting to impeach conservative President Park Geun-hye in December 2016 following a corruption scandal and months of public demonstrations in which millions of Koreans participated. In March 2017, the Korean Constitutional Court unanimously decided to uphold the impeachment, and new presidential elections consequently took place in May 2017. The elections were won by the leader of the opposition Democratic Party, Moon Jae-in, by a wide margin. The corruption scandal revealed major governance problems in South Korea, including collusion between the state and big business and a lack of institutional checks and balances able to prevent presidential abuses of power in a system that concentrates too much power in one office. Particularly striking were the revelations that under conservative Presidents Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye, the political opposition had been systematically suppressed by a state that impeded the freedom of the press, manipulated public opinion and created blacklists of artists who were seen as critical of the government. It was also revealed that the government had colluded with private businesses to create slush funds. However, the massive protests against President Park that began in October 2016 showed that the Korean public remains ready to defend its democracy and stand up against corruption. On 3 December 2016, an estimated 2 million people across the country took to the streets to demonstrate again President Park. -

2020 List of Board Members

2020 list of board members President Jae Seok Choi Gyeongsang National University President Elect Chul Hwan Kim SungKyunKwan University. Yeong Han Chun Hongik University. Jung ho Park Korea University. Il Hwan Kim Kangwon National University Hyang-yeol Yoo Korea South-East Power Co. Hahk Sung Lee LSIS Vice Presidents Byongjun Lee Korea Univ. In-Dong Kim Pukyong National University Sukcheol Kim Korea Electric Power Corporation Dong Jun Kim Cheongju University Kyung-Wan Koo Hoseo University Bongweon Bae Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power Sung Hwan Bae Kepco Energy Solution Cooperative Vice Presidents Jae Wan Ko Jinwoo System Deahwan Kim International Electric Vehicle Expo Keon Young Yi Kwangwoon University Auditors Jae Won Chang CIGRE Sung-Kwan Joo Korea Univ. General Affairs Ho Sung Jung Korea Railroad Research Institute Jun Min Cha Daejin University Finance Directors Tae Kyun Kim Korea Electric Power Corporation Chul-Won Park Gangneung–Wonju National University Planning Directors Hong Je Ryoo Chung-Ang university Jin Geun Shon Gachon University. Young Il Lee Seoul National Univ. of Science and Technology Nan Sook Lee Hanyang TEC Business Directors Miyoung Kim Howon University Eungsang Kim Korea Electrical Research Institute Pyeong-Shik Ji Korea National University of Transportation Jongbae Park Konkuk University Editorial Directors Neungsoo Park Konkuk University Seungtaek Kang Incheon National University Gil Soo Jang Korea University Sang-Yong Jung SungKyunKwan University. Academic Directors Jung Wook Woo Korea Electric Power Corporation Jung Wook Park Yonsei University Bang Wook Lee Hanyang University Kyeon Hur Yonsei University International Kyo-bum Lee Ajou University Cooperation Directors Junho Lee Hoseo University. Yong Tae Yoon Seoul National University. -

Uri Nara, Our Nation: Unification, Identity and the Emergence of a New Nationalism Amongst South Korean Young People

Uri nara, our nation: Unification, identity and the emergence of a new nationalism amongst South Korean young people. Emma Louise Gordon Campbell August 2011 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University ii DECLARATION Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own work. Emma Campbell iii iv Preface I first encountered Korea in 1996 when I was studying Chinese at a university in Beijing. Aside from a large group of British students from the University of Leeds, of which I was one, most other students learning Chinese were from South Korea. By the late 1990s, South Korean students already constituted the majority of foreign students in China. My room-mate was Korean as were most of my friends and as we spoke to each other in our common language Chinese I first came to discover Korea. My Korean friends introduced me to Korean food in restaurants run by Chaoxianzu or Joseonjok (Korean-Chinese) in the small Korea-town that had emerged to service the growing South Korean community in Beijing. During that stay in Beijing I also travelled to North Korea for the first time and then in the following year, 1998, to Seoul. It was during the 1990s that attitudes to North Korea amongst young South Koreans appear to have started their evolution. These changes coincided with the growth of travel by young South Koreans for study and leisure. Koreans travelling overseas were encountering foreigners of a similar age from countries such as the UK and discovering that they had more in common with them than the Joseonjok in the Korean restaurants of Beijing or North Koreans who, as South Koreans would soon learn, were facing starvation and escaping in ever growing numbers into China. -

Shin Korean Democracy April 2020.Indd

Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center Freeman Spogli Institute COMMENTARY april 2020 Korean Democracy is Sinking under the Guise of the Rule of Law Gi-Wook Shin also threatens the existing liberal international order. The “end of history” proclaimed the final victory of liberal democracy after the end of the Cold War, but it is nowhere to be seen today. nce again, Senator Bernie Sanders is whipping up a Rather, we are witnessing a worldwide democratic recession. storm in the U.S. presidential race. A self-described O“democratic socialist,” he is rallying the progres- sive wing of the Democratic Party behind him with a bold A Manichean logic of good and campaign pledge that includes universal single-payer health insurance, expanded construction of affordable housing, a evil is becoming prevalent, as is $15 minimum wage, tuition-free public college, and a wealth an emphasis on ideological purity tax. He has an unshakable base of fervent supporters—last year, his campaign raised approximately $96 million from five and moral superiority. million individual donors. Senator Sanders is criticized for holding radical political views that limit his ability to appeal to the wider electorate. South Korea is no exception to this trend. On the right, Nevertheless, he is still creating a sensation by riding on a wave there is the so-called Taegukgi brigade, named after Korea’s of anti-Trump sentiment. Antipathy toward President Donald national flag, waved by adherents at protests to express their Trump—known for his “America First” ideology and dispar- patriotism; on the left, there are the Moon-ppa, a label used agement of immigrants and minorities—is being expressed to refer to President Moon Jae-in’s zealous supporters. -

A U Tu M N 2 0 10 the ENGLISH CONNECTION

Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Task-Based Language Teaching: Development of Academic Proficiency By Miyuki Nakatsugawa ask-based language teaching has continued to attract interest among second language acquisition (SLA) researchers and language Tteaching professionals. However, theoretically informed principles for developing and implementing a task-based syllabus have yet to be fully established. The Cognition Hypothesis (Robinson, 2005) claims that pedagogical tasks should be designed and sequenced in order of increased cognitive complexity in order to promote language development. This article will look at Robinson ss approach to task-based syllabus design as a What’s Inside? Continued on page 8. TeachingInvited Conceptions Speakers By PAC-KOTESOLDr. Thomas S.C. 2010 Farrell English-OnlyConference ClassroomsOverview ByJulien Dr. Sang McNulty Hwang Comparing EPIK and JET National Elections 2010 By Tory S. Thorkelson ThePre-Conference Big Problem of SmallInterview: Words By JulieDr. Alan Sivula Maley Reiter NationalNegotiating Conference Identity Program PresentationKueilan ChenSchedule Email us at [email protected] at us Email Autumn 2010 Autumn To promote scholarship, disseminate information, and facilitate cross-cultural understanding among persons concerned with the teaching and learning of English in Korea. www.kotesol.org The English Connection Autumn 2010 Volume 14, Issue 3 THE ENGLISH CONNECTION A Publication of Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Features Cover Feature: Task-Based Language Teaching -- Development of Academic Proficiency 1 By Miyuki Nakatsugawa Contents Featurette: Using Korean Culture 11 By Kyle Devlin Featured Focus: Enhancing Vocabulary Building 12 By Dr. Sang Hwang Columns President s Message:t Roll Up Your Sleeves u 5 By Robert Capriles From the Editor ss Desk: The Spirit of Professional Development 7 By Kara MacDonald Presidential Memoirs: KOTESOL 2008-09 -- Growing and Thriving 14 By Tory S.