University Microfilms. a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana

The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 Elana Passman A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Donald M. Reid Dr. Christopher R. Browning Dr. Konrad H. Jarausch Dr. Alice Kaplan Dr. Lloyd Kramer Dr. Jay M. Smith ©2008 Elana Passman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ELANA PASSMAN The Cultivation of Friendship: French and German Cultural Cooperation, 1925-1954 (under the direction of Donald M. Reid) Through a series of case studies of French-German friendship societies, this dissertation investigates the ways in which activists in France and Germany battled the dominant strains of nationalism to overcome their traditional antagonism. It asks how the Germans and the French recast their relationship as “hereditary enemies” to enable them to become partners at the heart of today’s Europe. Looking to the transformative power of civic activism, it examines how journalists, intellectuals, students, industrialists, and priests developed associations and lobbying groups to reconfigure the French-German dynamic through cultural exchanges, bilingual or binational journals, conferences, lectures, exhibits, and charitable ventures. As a study of transnational cultural relations, this dissertation focuses on individual mediators along with the networks and institutions they developed; it also explores the history of the idea of cooperation. Attempts at rapprochement in the interwar period proved remarkably resilient in the face of the prevalent nationalist spirit. While failing to override hostilities and sustain peace, the campaign for cooperation adopted a new face in the misguided shape of collaborationism during the Second World War. -

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Abortion Reports Hard to Judge

C3 'sj 3 o fT1 >J O 04 THE ^ r n o ^ m o DENVER ARCHDIOCESAN EDITION O JC c c Thursday, Jan. 18, 1968 Vol. I Loretto Pope Makes Mo ^ Puts Nuns. Lay Staff Curia Changes; O n a Par Ameriean Named Vatican City — Pope Paul Vi's chang Sisters of Loretto teaching at Loretto replace Cardinal Luigi Traglia as Vicar ing of the "Old Guard” in the top olTIces Heights college will be hired and paid on General of Rome, with Cardinal Traglia in the Church continued this week, with the same basis us lay members of the transferred to Chancellor of the Holy faculty, under terms of a new policy two more non-Italian Cardinals — includ Roman Church and the selection of Car going into effect at the women’s school ing an American — named to top Vati dinal Egidio Vagnozzi to head the Vati June 1. can posts. can's finance commi.ssion. The newest appointments to the Ro An improved pay schedule for the fac Not in recent history have so many of man Curia’s high offices are those of ulty also will become effective the same the most important offices of the Roman Cardinal Francis Brennan of Philadel date, the college announced. Curia been changed. The moves reflect Under the new policy, salaries of nuns phia. named Prefect of the Congregation of Sacraments, and Cardinal Maximilian de the f^ipe’s intention of internationalizing teaching at the college will be paid in a the Curia, which has long been predomi Furstenberg of the Netherlands, named lump sum monthly U» the Congregation’s nantly Italian,. -

The Formulation of Nazi Policy Towards the Catholic Church in Bavaria from 1933 to 1936

CCHA Study Sessions, 34(1967), 57-75 The Formulation of Nazi Policy towards the Catholic Church in Bavaria from 1933 to 1936 J. Q. CAHILL, Ph.D. This study concentrates on the relations between church and state in Bavaria as a problem for Nazi policy-makers at the beginning of Nazi rule. Emphasizing the Nazi side of this problem provides a balance to those studies which either condemn or defend the actions of church leaders during the Nazi period. To understand the past is the first goal of historians. A better understanding of the attitudes and actions of National Socialist leaders and organizations toward the Catholic Church will provide a broader perspective for judging the actions of churchmen. Such an approach can also suggest clues or confirm views about the basic nature of Nazi totalitarianism. Was National Socialism essentially opposed to Catholicism ? Was its primary emphasis on domestic policy or on foreign policy ? Perhaps basic to these questions is whether Nazism was monolithic in its ruling structure or composed of diverse competing groups. I believe that the question of Nazi church policy is worth studying for its own sake, but it has further implications. The materials used for this study are mainly microfilms of documents from the Main Archive of the National Socialist German Worker's Party in Munich, and from the files of the Reich Governor in Bavaria. An important part of these documents is made up of police reports, which, however, include more than mere descriptions of crimes and charges. But the nature of this material poses the danger of emphasizing those elements for which we have the most documentation. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

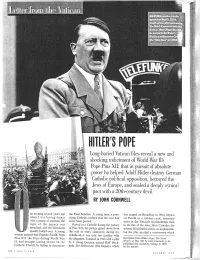

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

PAG. 3 / Attualita Ta Grave Questione Del Successore Di Papa Giovanni Roma

FUnitd / giovedi 6 giugno 1963 PAG. 3 / attualita ta grave questione del successore di Papa Giovanni Roma il nuovo ILDEBRANDO ANTONIUTTI — d Spellman. E' considerate un • ron- zione statunltense dl Budapest dopo ITALIA Cardinale di curia. E' ritenuto un, calliano ». - --_., ^ <. la sua partecipazione alia rivolta del • moderate*, anche se intlmo di Ot 1956 contro il regime popolare. Non CLEMENTE MICARA — Cardinale taviani. E' nato a Nimis (Udine) ALBERT MEYER — Arcivescovo si sa se verra at Conclave. Sono not) di curia, Gran Cancelliere dell'Uni- nel 1898.' Per molti anni nunzio a d) Chicago. E' nato a Milxankee nel 1903. Membro di varie congregaziont. i recenti sondaggl della Santa Sede verslta lateranense. E* nato a Fra- Madrid; sostenuto dai cardinal! spa- per risotvere il suo caso. ficati nel 1879. Noto come • conserva- gnoli. JAMES MC. INTYRE — Arclve- tore >; ha perso molta dell'influenza EFREM FORNI — Cardinale di scovo di Los Angeles. E' nato a New che aveva sotto Pic XII. E' grave. York net 1886. Membro della con mente malato. , curia. E' nato a Milano net 1889. E' OLANDA stato nominate nel 1962. gregazione conclstoriale. GIUSEPPE PIZZARDO — Cardina JOSEPH RITTER — Arcivescovo BERNARD ALFRINK — Arcivesco le di curia, Prefetto delta Congrega- '« ALBERTO DI JORIO — Cardinale vo di Utrecht. Nato a Nljkeik nel di curia. E' nato a Roma nel 1884. di Saint Louis. E' nato a New Al zione dei seminar). E' nato a Savona bany nel 1892. 1900. Figura di punta degli innovator! nel 1877. SI e sempre situate all'estre. Fu segretario nel Conclave del 1958. sia nella rivendicazione dell'autono- ma destra anche nella Curia romana. -

Hitler Und Bayern Beobachtungen Zu Ihrem Verhältnis

V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 BAYERISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE · JAHRGANG 2004, HEFT 4 Erstversand WALTER ZIEGLER Hitler und Bayern Beobachtungen zu ihrem Verhältnis Vorgetragen in der Sitzung vom 6. Februar 2004 MÜNCHEN 2004 VERLAG DER BAYERISCHEN AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN In Kommission beim Verlag C. H. Beck München V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 ISSN 0342-5991 ISBN 3 7696 1628 6 © Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften München, 2004 Gesamtherstellung: Druckerei C. H. Beck Nördlingen Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 Inhalt 1. Zur Methode ............................... 8 2. Hitlers Aufstieg in Bayern ...................... 16 3. Im Regime ................................ 33 4. Verhältnis zu den bayerischen Traditionen ........... 73 5. Veränderungen im Krieg ....................... 94 Bildnachweis ................................. 107 V V V V V V V V Druckerei C. H . Beck V V V V Medien mit Zukunft V Ziegler, Phil.-hist. Klasse 04/04 V V V VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV V .....................................VVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVVV Erstversand, 20.07.2004 Abb. 1: Ein bayerischer Kanzler? Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler bei seiner Wahlrede am 24. -

Die Neue Er2iehung Und Der Neue Mensch 41

INHALT Vorwort 9 ErsterTeil: 1933 bis 1937 11 Zeittafel 12 DIE RELIGIONSPOLITIK HITLERS GEGEN DIE KATHOLISCHE KIRCHE IM JAHRE 1933 15 Hitlers Angst vor dem politischen Katholizismus 15 Das Reichskonkordat als innen- und auBenpolitisches Propagandamittel Hitlers 16 Die politischen Vorteile, die Hitler vom Konkordat erhoffte 17 Vorwurfe gegen den Papst wegen AbschluB des Konkordats 18 DIE KIRCHE IM SOG DER GLEICHSCHALTUNG 21 Der aus der Zeit vor 1933 bestehende Gegensatz zwischen katholiseher Kirche und dem Nationalsozialismus 21 Hitler zeigt nach auBen Entgegenkommen 22 Derfruhe Beginn des Kirchenkampfes 23 Die Bischofe protestieren gegen den Kirchenkampf und die Verletzung der Menschenrechte 23 Hitler belugt den Breslauer Kardinal 26 Konkordat oder nicht 27 DER KIRCHENKAMPF VERSCHARFT SICH NACH ABSCHLUSS DES REICHSKONKORDATS 29 Unsicherheit in historischen Darstellungen 29 Hitlers Haltung zur katholischen Kirche 30 Hitler laBt im engen Kreis die Maske fallen 32 DIE VOLLSTRECKER DER RELIGIONSPOLITISCHEN PLANE HITLERS 34 Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei 35 Der gefurchtete Gestapochef Reinhard Heydrich 36 Martin Bormann, der zweite Mann nach Hitler 38 Alfred Rosenberg, der Chefideologe der nationalsozialistischen Weltanschauung 38 DIE NEUE ER2IEHUNG UND DER NEUE MENSCH 41 Hitler als Erzieher der Deutschen 41 Grundsatze der NS-Erziehung 42 DIE DEUTSCHEN BISCHOFE UNTER HITLERS PARTEI UND STAAT 45 Die Bischofskonferenzen 45 Adolf Kardinal Bertram, der Vorsitzende der Fuldaer Bischofskonferenz 1859-1945 48 Michael -

Between the Wars

Day #50 • 3/7-8 Between the Wars A Whole Lotta Changin’ Goin’ On http://www.iamsyria.org/ Warning Signs of Genocide: http://967670192324838111.weebly.com/ Corny Jokes 1. What are twins’ favorite fruit? PEARS! 2. What is the king of all school supplies? THE RULER! 3. What do you call a flock of sheep tumbling down a hill? A LAMBSLIDE! Foreign Imperialism Inspires NATIONALIST Movements Events in China and India Lead to the Rise of Nationalism 1842 1857 1885 1900 1906 Foreign Imperialism Inspires NATIONALIST Movements Events in China and India Lead to the Rise of Nationalism Indians help the gain ; communists British in WWI Support from Chinese peasants Support Chinese from Long March Long 1911 1919 1921 1930 1934-35 Foreign Imperialism Inspires NATIONALIST Movements Events in China and India Lead to the Rise of Nationalism Using the timeline above, how would you describe the political, economic and social climate of China and India in the early 20th Century? Nationalists Respond to Foreign Influence China Goal of Movement • End Foreign Rule Nationalists Respond to Foreign Influence China Nationalist Leader • Sun Yixian • Overthrows the last Chinese dynasty (Qing) Nationalists Respond to Foreign Influence China Strategy to Achieve Goal Overthrow dynasty Unite China Modernize Emperor Qianlong Empress Cixi Sun Yixian Sun Yixian and his wife Nationalists Respond to Foreign Influence China Divisions within the Movement • Nationalists: led by corrupt Jiang Jieshi; supported by the West • Communists: led by Mao Zedong; supported by Chinese peasants Nationalists Respond to Foreign Influence China Results of the Movement: –Overthrow of Qing monarchs in 1911 by Sun Yixian –22-year civil war • (nationalists vs. -

German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945

Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Guy B. Aldridge May 2015 © 2015 Guy B. Aldridge. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 by GUY B. ALDRIDGE has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Mirna Zakic Assistant Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract ALDRIDGE, GUY B., M.A., May 2015, History Forgotten and Unfulfilled: German Transitions in the French Occupation Zone, 1945- 1949 Director of Thesis: Mirna Zakic This thesis examines how local newspapers in the French Occupation Zone of Germany between 1945 and 1949 reflected social change. The words of the press show that, starting in 1945, the Christian narrative was the lens through which ‘average’ Germans conceived of their past and present, understanding the Nazi era as well as war guilt in religious terms. These local newspapers indicate that their respective communities made an early attempt to ‘come to terms with the past.’ This phenomenon is explained by the destruction of World War II, varying Allied approaches to German reconstruction, and unique social conditions in the French Zone. The decline of ardent religiosity in German society between 1945 and 1949 was due mostly to increasing Cold War tensions as well as the return of stability and normality.