A Socio-Historical Analysis of Public Education in Chicago As Seen in the Naming of Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political History of Chicago." Nobody Should Suppose That Because the Fire and Police Depart Ments Are Spoken of in This Book That They Are Politi Cal Institutions

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF CHICAGO. BY M. L. AHERN. First Edition. (COVERING THE PERIOD FROM 1837 TO 1887.) LOCAL POLITICS, FROM THE CITY'S BIRTH; CHICAGO'S MAYORS, .ALDER MEN AND OTHER OFFICIALS; COUNTY AND FE.DERAL OFFICERS; THE FIRE AND POLICE DEPARTMENTS; THE HAY- MARKET HORROR; MISCELLANEOUS. CHIC.AGO: DONOHUE & HENNEBEaRY~ PRINTERS. AND BINDERS. COPYRIGHT. 1886. BY MICHAEL LOFTUS AHERN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. CONTENTS. PAGE. The Peoples' Party. ........•••.•. ............. 33 A Memorable Event ...... ••••••••••• f •••••••••••••••••• 38 The New Election Law. .................... 41 The Roll of Honor ..... ............ 47 A Lively Fall Campaign ......... ..... 69 The Socialistic Party ...... ..... ......... 82 CIDCAGO'S MAYORS. William B. Ogden .. ■ ■ C ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ e ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ti ■ 87 Buckner S. Morris. .. .. .. .... ... .... 88 Benjamin W. Raymond ... ........................... 89 Alexander Lloyd .. •· . ................... ... 89 Francis C. Sherman. .. .... ·-... 90 Augustus Garrett .. ...... .... 90 John C. Chapin .. • • ti ••• . ...... 91 James Curtiss ..... .. .. .. 91 James H. Woodworth ........................ 91 Walter S. Gurnee ... .. ........... .. 91 Charles M. Gray. .. .............. •· . 92 Isaac L. Milliken .. .. 92 Levi D. Boone .. .. .. ... 92 Thomas Dyer .. .. .. .. 93 John Wentworth .. .. .. .. 93 John C. Haines. .. .. .. .. ... 93 ,Julian Rumsey ................... 94 John B. Rice ... ..................... 94 Roswell B. Mason ..... ...... 94 Joseph Medill .... 95 Lester L. Bond. ....... 96 Harvey D. Colvin -

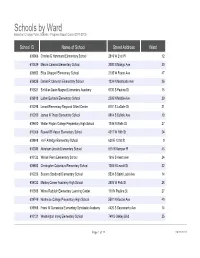

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

The Chicago City Manual, and Verified by John W

CHICAGO cnT MANUAL 1913 CHICAGO BUREAU OF STATISTICS AND MUNICIPAL UBRARY ! [HJ—MUXt mfHi»rHB^' iimiwmimiimmimaamHmiiamatmasaaaa THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY I is re- The person charging this material or before the sponsible for its return on Latest Date stamped below. underlining of books Theft, mutilation, and disciplinary action and may are reasons for from the University. result in dismissal University of Illinois Library L161-O-1096 OFFICIAL CITY HALL DIRECTORY Location of the Several City Departments, Bureaus and Offices in the New City Hall FIRST FLOOR The Water Department The Fire Department Superintendent, Bureau of Water The Fire Marshal Assessor, Bureau of Water Hearing Room, Board of Local Improve^ Meter Division, Bureau of Water ments Shut-Off Division, Bureau of Water Chief Clerk, Bureau of Water Department of the City Clerk Office of the City Clerk Office of the Cashier of Department Cashier, Bureau of Water Office of the Chief Clerk to the City Clerk Water Inspector, Bureau of Water Department of the City Collector Permits, Bureau of Water Office of the City Collector Plats, Bureau of Water Office of the Deputy City Collector The Chief Clerk, Assistants and Clerical Force The Saloon Licensing Division SECOND FLOOR The Legislative Department The Board's Law Department The City Council Chamber Board Members' Assembly Room The City Council Committee Rooms The Rotunda Department of the City Treasurer Office of the City Treasurer The Chief Clerk and Assistants The Assistant City Treasurer The Cashier and Pay Roll Clerks -

18-0124-Ex1 5

18-0124-EX1 5. Transfer from George Westinghouse High School to Education General - City Wide 20180046075 Rationale: FY17 School payment for the purchase of ventra cards between 2/1/2017 -6/30/2017 Transfer From: Transfer To: 53071 George Westinghouse High School 12670 Education General - City Wide 124 School Special Income Fund 124 School Special Income Fund 53405 Commodities - Supplies 57915 Miscellaneous - Contingent Projects 290003 Miscellaneous General Charges 600005 Special Income Fund 124 - Contingency 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers 002239 Internal Accounts Book Transfers Amount: $1,000 6. Transfer from Early College and Career - City Wide to Al Raby High School 20180046597 Rationale: Transfer funds for printing services. Transfer From: Transfer To: 13727 Early College and Career - City Wide 46471 Al Raby High School 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 369 Title I - School Improvement Carl Perkins 54520 Services - Printing 54520 Services - Printing 212041 Guidance 212041 Guidance 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) 322022 Career & Technical Educ. Improvement Grant (Ctei) Fy18 Fy18 Amount: $1,000 7. Transfer from Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide to George Henry Corliss High School 20180046675 Rationale: CPS 7132510. FURNISH LABOR, MATERIALS & EQUIPMENT TO PERFORM A COMBUSTION ANALYSIS-CALIBRATE BURNER, REPLACE & TEST FOULED PARTS: FLAME ROD, WIRE, IGNITOR, CABLE, ETC... ON RTUs 18, 16, 14 & 20 Transfer From: Transfer To: 11880 Facility Opers & Maint - City Wide 46391 George Henry Corliss High School 230 Public Building Commission O & M 230 Public Building Commission O & M 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 56105 Services - Repair Contracts 254033 O&M South 254033 O&M South 000000 Default Value 000000 Default Value Amount: $1,000 8. -

Shaping Chicago's Sense of Self: Chicago Journalism in The

Richard Junger. Becoming the Second City: Chicago's Mass News Media, 1833-1898. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010. xiv + 235 pp. $25.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-252-07785-2. Reviewed by Jon Bekken Published on Jhistory (August, 2011) Commissioned by Donna Harrington-Lueker (Salve Regina University) In this book, Richard Junger explores the de‐ sensibilities that often dominated local politics. velopment of the Chicago press in the nineteenth This is a particularly valuable study because it century (from 1833, when the city’s frst newspa‐ leads Junger to focus on a period that has re‐ per appeared, until 1898), looking at several key ceived relatively little attention, particularly from moments to understand the press’s role in shap‐ journalism historians, and once again reminds us ing the city’s development and its sense of itself. that the practice of journalism by no means uni‐ The jacket copy calls attention to Junger’s discus‐ formly followed the progressive narrative that sion of the 1871 fre, the Haymarket Square inci‐ still too often shapes our approaches. dent, the Pullman Strike, and the World’s My major criticism of this very useful work is Columbian Exposition--all from the fnal two the extent to which it persists in treating Chicago decades of the study--but this material occupies journalism as a singular entity, and one distinct less than half the book, and is not its most signifi‐ from other centers of social power. Junger’s subti‐ cant contribution. Junger’s key focus is the path tle refers to “Chicago’s Mass News Media,” per‐ that led Chicago to become America’s second city-- haps in recognition of the fact that his focus on a campaign of civic boosterism that obviously English-language daily newspapers excludes the aimed significantly higher, but nonetheless played vast majority of titles published in the city. -

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River Helps Teachers Use the Chicago River As a Context for Learning and a Setting for Service

Chicago River Schools Network Through the CRSN, Friends of the Chicago River helps teachers use the Chicago River as a context for learning and a setting for service. By connecting the curriculum and students to a naturalc resource rightr in theirs backyard, nlearning takes on new relevance and students discover that their actions can make a difference. We support teachers by offering teacher workshops, one-on-one consultations, and equipment for loan, lessons and assistance on field trips. Through our Adopt A River School program, schools can choose to adopt a site along the Chicago River. They become part of a network of schools working together to monitor and Makingimprove Connections the river. Active Members of the Chicago River Schools Network (2006-2012) City of Chicago Eden Place Nature Center Lincoln Park High School * Roots & Shoots - Jane Goodall Emmet School Linne School Institute ACE Tech. Charter High School Erie Elementary Charter School Little Village/Lawndale Social Rush University Agassiz Elementary Faith in Place Justice High School Salazar Bilingual Education Center Amundsen High School * Farnsworth Locke Elementary School San Miguel School - Gary Comer Ancona School Fermi Elementary Mahalia Jackson School Campus Anti-Cruelty Society Forman High School Marquez Charter School Schurz High School * Arthur Ashe Elementary Funston Elementary Mather High School Second Chance High School Aspira Haugan Middle School Gage Park High School * May Community Academy Shabazz International Charter School Audubon Elementary Galapagos Charter School Mitchell School St. Gall Elementary School Austin High School Galileo Academy Morgan Park Academy St. Ignatius College Prep * Avondale School Gillespie Elementary National Lewis University St. -

Cta Student Ventra Card Distribution Schoools*

CTA STUDENT VENTRA CARD DISTRIBUTION SCHOOOLS* In addition to all Chicago Public Schools, the following schools may issue Student Ventra Cards only to their enrolled students: 1 Academy of Scholastic Achievement 38 Chicago International Charter Schools - 2 Ace Tech Charter High School Quest 3 Ada S. McKinley Lakeside Academy High 39 Chicago Jesuit Academy School 40 Chicago Math & Science Academy 4 Alain Locke Charter School 41 Chicago Talent Development High School 5 Alcuin Montessori School 42 Chicago Tech Academy 6 Amandla Charter School 43 Chicago Virtual Charter School 7 Argo Community High School 44 Chicago Waldorf School 8 ASN Preparatory Institute 45 Children Of Peace School 9 Aspira - Antonia Pantoja High School 46 Christ the King College Prep 10 Aspira - Early College High School 47 Christ the King Lutheran School 11 Aspira - Haugan Middle School 48 Community Christian Alternative Academy 12 Aspira Mirta Ramirez Computer Science High 49 Community School District 300 School 50 Community Youth Development Institute 13 Austin Career Education Center 51 Cornerstone Academy 14 Baker Demonstration School 52 Courtenay Elementary Language Arts 15 Banner Academy Center 16 Banner Learning School 53 Cristo Rey Jesuit High School 17 Betty Shabazz International Charter School 54 Delta/Summit Learning Center 18 Bloom Township High School - Dist 206 55 District 300 19 Brickton Montessori School 56 Dodge Renaissance Academy 20 Bronzeville Lighthouse Charter School 57 Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School 21 Brother Rice High School 58 Dwight D. -

Action Civics Showcase

16th annual Action Civics showcase Bridgeport MAY Art Center 10:30AM to 6:30PM 22 2018 DEMOCRACY IS A VERB WELCOME to the 16th annual Mikva Challenge ASPEN TRACK SCHOOLS Mason Elementary Action Civics Aspen Track Sullivan High School Northside College Prep showcase The Aspen Institute and Mikva Challenge have launched a partnership that brings the best of our Juarez Community Academy High School collective youth activism work together in a single This has been an exciting year for Action initiative: The Aspen Track of Mikva Challenge. Curie Metropolitan High School Civics in the city of Chicago. Together, Mikva and Aspen have empowered teams of Chicago high school students to design solutions to CCA Academy High School Association House Over 2,500 youth at some of the most critical issues in their communities. The result? Innovative, relevant, powerful youth-driven High School 70 Chicago high schools completed solutions to catalyze real-world action and impact. Phillips Academy over 100 youth action projects. High School We are delighted to welcome eleven youth teams to Jones College Prep In the pages to follow, you will find brief our Action Civics Showcase this morning to formally Hancock College Prep SCHEDULE descriptions of some of the amazing present their projects before a panel of distinguished Gage Park High School actions students have taken this year. The judges. Judges will evaluate presentations on a variety aspen track work you will see today proves once again of criteria and choose one team to win an all-expenses paid trip to Washington, DC in November to attend the inaugural National Youth Convening, where they will be competition that students not only have a diverse array able to share and learn with other youth leaders from around the country. -

State School Year LEA Name School Name Reading Proficiency Target

Elementary/ Middle School Reading Reading Math Math Other School Proficiency Participation Proficiency Participation Academic Graduation School Improvement Status for SY State Year LEA Name School Name Target Target Target Target Indicator Rate 2007-08 Illinois 2006-07 EGYPTIAN CUSD 5 EGYPTIAN SR HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MERIDIAN CUSD 101 MERIDIAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 ROCKFORD SD 205 MCINTOSH SCIENCE AND TECH MAGNET X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CENTRALIA HSD 200 CENTRALIA HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MAYWOOD-MELROSE PARK-BROADVIEW 89 LEXINGTON ELEM SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 FOREST PARK SD 91 FOREST PARK MIDDLE SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 POSEN-ROBBINS ESD 143-5 POSEN ELEM SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 SOUTH HOLLAND SD 151 COOLIDGE MIDDLE SCHOOL X y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 COUNTRY CLUB HILLS SD 160 MEADOWVIEW SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 OAK PARK - RIVER FOREST SD 200 OAK PARK & RIVER FOREST HIGH SCH X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 MAINE TOWNSHIP HSD 207 MAINE EAST HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 LEYDEN CHSD 212 WEST LEYDEN HIGH SCHOOL X y X y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 NILES TWP CHSD 219 NILES NORTH HIGH SCHOOL y y Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CITY OF CHICAGO SD 299 CHICAGO DISCOVERY ACADEMY HS X y X y X Corrective Action Illinois 2006-07 CITY OF CHICAGO SD 299 PHOENIX MILITARY ACADEMY HS X y X y X -

State of the Arts Report Draws Many District-Level Conclusions; the Data Behind These Conclusions Are Equally Powerful When Examined at the School Level

STATE OF THE ARTS IN CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PROGRESS REPORT | 2016–17 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 6 CREATIVE SCHOOLS SURVEY PARTICIPATION 16 THE ARTS IN CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS 20 • Creative Schools Certification 21 • Staffing 30 • Instructional Minutes and Access 38 • Disciplines and Depth 42 • Arts Assets in Schools 45 • Arts Discipline Offerings 48 COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIPS 50 FUNDING 58 CPS ARTS EDUCATION PLAN PROGRESS 64 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX 72 • References 73 • Data Notes 74 • Glossary 76 CREATIVE SCHOOLS CERTIFICATION RUBRIC 80 INGENUITY | STATE OF THE ARTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE The 2016–17 State of the Arts in Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Progress Report highlights the progress CPS and Chicago’s arts SUMMARY education community are making toward fulfilling the goal— and the promise to CPS students—articulated in the 2012 CPS Arts Education Plan: that the arts should be brought to every child, in every grade, in every school. This year, as in each year since the Arts Education Plan was released, the progress report identifies some important gains. Foremost among these is that a higher percentage of CPS schools than ever before, serving a higher share of CPS students than ever before, are meeting the criteria to be rated as Strong or Excelling in the arts. This achievement is particularly encouraging considering the financial challenges the district has faced in recent years. Despite a frequently uncertain and challenging financial climate, and with additional arts gains clearly needed, data reflect that both the district and principals have continued to prioritize arts education in their schools. -

Obituary Index 3Dec2020.Xlsx

Last First Other Middle Maiden ObitSource City State Date Section Page # Column # Notes Naber Adelheid Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 9/26/1928 1 3 Naber Anna M. Carrollton Gazette Patriot Carrolton IL 9/23/1960 1 2 Naber Bernard Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 11/17/1910 1 6 Naber John B. Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 6/13/1941 1 1 Nace Joseph Lewis Carthage Republican Carthage IL 3/8/1899 5 2 Nachtigall Elsie Meler Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 3/27/1909 15 1 Nachtigall Henry C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 11/30/1909 18 4 Nachtigall William C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 10/5/1925 38 3 Nacke Mary Schleper Effingham Democrat Effingham IL 8/6/1874 3 4 Nacofsky Lillian Fletcher Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 2/22/1922 29 1 Naden Clifford Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1990 Countywide 2 2 Naden Earl O. Waukegan News Sun Waukegan IL 11/2/1984 7A 4 Naden Elizabeth Broadbent Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 1/17/1900 8 4 Naden Isaac Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 2/28/1900 4 1 Naden James Darby Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/25/1935 4 5 Naden Jane Green Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 4/10/1912 9 3 Naden John M. Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 9/13/1944 5 4 Naden Martha Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/6/1866 3 1 Naden Obadiah Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1911 1 1 Naden Samuel Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 6/17/1942 7 1 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/15/1878 4 3 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/8/1878 1 4 Naden Thomas Kendall County -

The 2014-15 Chicago Area Schweitzer Fellows

The 2014-15 Chicago Area Schweitzer Fellows Harlean Ahuja, Midwestern University, College of Dental Medicine Harlean proposes to initiate "Right from the Start," an interdisciplinary health curriculum for low income elementary school students living in the western suburbs. She will provide interactive workshops to educate children on the importance of making and implementing healthy lifestyle choices and encourage them to actively begin developing healthy lifelong habits. Kelli Bosak, University of Chicago, School of Social Service Administration Kelli plans to work with women in the process of community re-entry or in residential programs affiliated with the Cook County Sheriff Women’s Justice Program. She will lead a weekly yoga and mindfulness group to aid them in their stress reduction, health education, and empowerment. Eddie D. Burks, Loyola University Chicago, Community Counseling Eddie will initiate psycho-education interventions and a support group to assist LGBTQ youth, primarily those who are Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) wards of the state. His program will provide literacy on legal rights pertaining to DCFS LGBT wards of the state, skills to help with positive development of self-esteem and acceptance of sexual orientation, and coping skills to deal with mental health related issues in relation to their sexual orientation. Autumn Burnes, Rush University, Rush Medical College Autumn proposes to teach adult English as a Second Language through the Lincoln United Methodist Church in Pilsen. The classes will emphasize health literacy on topics such as diabetes and hypertension and help connect participants to health resources in the community. Rebecca Charles, Chicago-Kent College of Law and University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Public Health Rebecca will partner with Heartland Health Center to educate immigrant populations on culturally appropriate nutrition interventions for better diabetes control.