Erwin L. Hahn 1921–2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Science-Based Cost- Effective Pathways Forward?

Sponsors Institute of Atomic and Molecular Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwan PIRE-ECCI Program, UC Santa Barbara, USA Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Germany National Science Council, Taiwan Organizing committee Dr. Kuei-Hsien Chen (IAMS, Academia Sinica, Taiwan) Dr. Susannah Scott (University of California - Santa Barbara, USA) Dr. Alec Wodtke (University of Göttingen & Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Germany) Table of Contents General Information .............................................................................................. 1 Program for Sustainable Energy Workshop ....................................................... 3 I01 Dr. Alec M. Wodtke Beam-surface Scattering as a Probe of Chemical Reaction Dynamics at Interfaces ........................................................................................................... 7 I02 Dr. Kopin Liu Imaging the steric effects in polyatomic reactions ............................................. 9 I03 Dr. Chi-Kung Ni Energy Transfer of Highly Vibrationally Excited Molecules and Supercollisions ................................................................................................. 11 I04 Dr. Eckart Hasselbrink Energy Conversion from Catalytic Reactions to Hot Electrons in Thin Metal Heterostructures ............................................................................................... 13 I05 Dr. Jim Jr-Min Lin ClOOCl and Ozone Hole — A Catalytic Cycle that We Don’t Like ............... 15 I06 Dr. Trevor W. Hayton Nitric Oxide Reduction Mediated by a Nickel Complex -

Reversed out (White) Reversed

Berkeley rev.( white) Berkeley rev.( FALL 2014 reversed out (white) reversed IN THIS ISSUE Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory Tabletop Physics Bringing More Women into Physics ALUMNI NEWS AND MORE! Cover: The MAVEN satellite mission uses instrumentation developed at UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory to explore the physics behind the loss of the Martian atmosphere. It’s a continuation of Berkeley astrophysicist Robert Lin’s pioneering work in solar physics. See p 7. photo credit: Lockheed Martin Physics at Berkeley 2014 Published annually by the Department of Physics Steven Boggs: Chair Anil More: Director of Administration Maria Hjelm: Director of Development, College of Letters and Science Devi Mathieu: Editor, Principal Writer Meg Coughlin: Design Additional assistance provided by Sarah Wittmer, Sylvie Mehner and Susan Houghton Department of Physics 366 LeConte Hall #7300 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-7300 Copyright 2014 by The Regents of the University of California FEATURES 4 12 18 Berkeley’s Space Tabletop Physics Bringing More Women Sciences Laboratory BERKELEY THEORISTS INVENT into Physics NEW WAYS TO SEARCH FOR GOING ON SIX DECADES UC BERKELEY HOSTS THE 2014 NEW PHYSICS OF EDUCATION AND SPACE WEST COAST CONFERENCE EXPLORATION Berkeley theoretical physicists Ashvin FOR UNDERGRADUATE WOMEN Vishwanath and Surjeet Rajendran IN PHYSICS Since the Space Lab’s inception are developing new, small-scale in 1959, Berkeley physicists have Women physics students from low-energy approaches to questions played important roles in many California, Oregon, Washington, usually associated with large-scale of the nation’s space-based scientific Alaska, and Hawaii gathered on high-energy particle experiments. -

The Impact of NMR and MRI

WELLCOME WITNESSES TO TWENTIETH CENTURY MEDICINE _____________________________________________________________________________ MAKING THE HUMAN BODY TRANSPARENT: THE IMPACT OF NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING _________________________________________________ RESEARCH IN GENERAL PRACTICE __________________________________ DRUGS IN PSYCHIATRIC PRACTICE ______________________ THE MRC COMMON COLD UNIT ____________________________________ WITNESS SEMINAR TRANSCRIPTS EDITED BY: E M TANSEY D A CHRISTIE L A REYNOLDS Volume Two – September 1998 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 1998 First published by the Wellcome Trust, 1998 Occasional Publication no. 6, 1998 The Wellcome Trust is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 186983 539 1 All volumes are freely available online at www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Tansey E M, Christie D A, Reynolds L A. (eds) (1998) Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 2. London: Wellcome Trust. Key Front cover photographs, L to R from the top: Professor Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, speaking (NMR) Professor Robert Steiner, Professor Sir Martin Wood, Professor Sir Rex Richards (NMR) Dr Alan Broadhurst, Dr David Healy (Psy) Dr James Lovelock, Mrs Betty Porterfield (CCU) Professor Alec Jenner (Psy) Professor David Hannay (GPs) Dr Donna Chaproniere (CCU) Professor Merton Sandler (Psy) Professor George Radda (NMR) Mr Keith (Tom) Thompson (CCU) Back cover photographs, L to R, from the top: Professor Hannah Steinberg, Professor -

BIOLOGY 639 SCIENCE ONLINE the Unexpected Brains Behind Blood Vessel Growth 641 THIS WEEK in SCIENCE 668 U.K

4 February 2005 Vol. 307 No. 5710 Pages 629–796 $10 07%.'+%#%+& 2416'+0(70%6+10 37#06+6#6+8' 51(69#4' #/2.+(+%#6+10 %'..$+1.1); %.10+0) /+%41#44#;5 #0#.;5+5 #0#.;5+5 2%4 51.76+105 Finish first with a superior species. 50% faster real-time results with FullVelocity™ QPCR Kits! Our FullVelocity™ master mixes use a novel enzyme species to deliver Superior Performance vs. Taq -Based Reagents FullVelocity™ Taq -Based real-time results faster than conventional reagents. With a simple change Reagent Kits Reagent Kits Enzyme species High-speed Thermus to the thermal profile on your existing real-time PCR system, the archaeal Fast time to results FullVelocity technology provides you high-speed amplification without Enzyme thermostability dUTP incorporation requiring any special equipment or re-optimization. SYBR® Green tolerance Price per reaction $$$ • Fast, economical • Efficient, specific and • Probe and SYBR® results sensitive Green chemistries Need More Information? Give Us A Call: Ask Us About These Great Products: Stratagene USA and Canada Stratagene Europe FullVelocity™ QPCR Master Mix* 600561 Order: (800) 424-5444 x3 Order: 00800-7000-7000 FullVelocity™ QRT-PCR Master Mix* 600562 Technical Services: (800) 894-1304 Technical Services: 00800-7400-7400 FullVelocity™ SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix 600581 FullVelocity™ SYBR® Green QRT-PCR Master Mix 600582 Stratagene Japan K.K. *U.S. Patent Nos. 6,528,254, 6,548,250, and patents pending. Order: 03-5159-2060 Purchase of these products is accompanied by a license to use them in the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Technical Services: 03-5159-2070 process in conjunction with a thermal cycler whose use in the automated performance of the PCR process is YYYUVTCVCIGPGEQO covered by the up-front license fee, either by payment to Applied Biosystems or as purchased, i.e., an authorized thermal cycler. -

PHYS 212 James Scholar Assignment #4

Name ________________________ Net ID_______________ TA Name____________________ Discussion Section________ PHYS 212 James Scholar Assignment #4 Due: 5:00 pm Friday, October 28, 2011 The problems are to be done on paper, showing all work . Again, the presentation should be neat, legible , and easy to follow . {Remember to include your name, netID, and Discussion section and ideally TA name on the top of the page! Please turn in your assignment into the Grading Box labeled “Physics 212 James Scholars”, located on the 2 nd floor, in the interpass between Loomis and MRL (Materials Research Lab). The interpass is down the hall about 10 meters east of Room 262 Loomis, where half of you have your Lab.} In this assignment you will learn all about magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or as it used to be called, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging (the name was changed because the average Joe was afraid of anything with the word nuclear, or 'nucular', as George W. would say!). UIUC Chemistry professor Paul Lauterbur (who passed away in March 2007) won the 2003 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his development of MRI. Lauterbur shared the Prize with Sir Peter Mansfield of the University of Nottingham in England. Mansfield was a research associate in the department of physics at Illinois from 1962-1964. Adding to these two the Physics Nobel Prize awarded that year to UIUC Physicist Anthony Leggett ( http://www.news.uiuc.edu/NEWS/03/1007nobelphys.html) makes a total of three Nobel winners for UIUC in 2003. (Also, it should be not be overlooked that UIUC microbiologist Professor Carl Woese received the 2003 Crafoord Prize, awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to recognize accomplishments in scientific fields not covered by the Nobel Prizes; for details see http://www.news.uiuc.edu/news/03/0925woeseaward.html .) There are many excellent MRI references and tutorials available. -

William Aaron Nierenberg Feb. 13,1919

William Aaron Nierenberg Feb. 13,1919- William Aaron Nierenberg was born on February 13, 1919 at 228 E. 13th St. in New York City on what was then the Lower East Side -- it is now the "East Village". While it is true that his father and his father's family had lived on the Lower East Side (Houston Street) when they had emigrated to America (his father in 1906), it was an accident that his birthplace was there. His parents, Joseph and Minnie (Drucker) had moved to Manhattan from the Bronx to be near the Sloan Lying in Hospital for his birth. His parents had lost their first infant child to tuberculosis of the brain from tainted milk and his mother was naturally very nervous about the new child's safety. He only lived in Manhattan for the next four months and the rest of his years in New York City, both before and after his marriage, were spent in the Bronx except for time in Paris as a physics student. There is essentially no specific knowledge of his antecedents. His paternal grandfather's given name was Hirsch and his paternal grandmother's name was Bertha. He had no knowledge whatsoever of his maternal forebears. His parent's gravestone showed his grandfather (therefore his father and he himself) to be a Levi, of the tribe blessed by the Lord. His mother's gravestone describes her as a "daughter of Abraham" since her antecedents were unknown to the burial society. (Many years later. most surprisingly, her birth certificate showed up! This is the one that Aba's daughter gave me a copy of. -

Two-Dimensional NMR Investigations of the Dynamic Conformations of Phospholipids and Liquid Crystals

LBNL-42162 |BERKELEY LAB] Two-Dimensional NMR Investigations of the Dynamic Conformations of Phospholipids and Liquid Crystals Mei Hong Materials Sciences Division RECEIVE MAR 1 8 1999 May 1996 Ph.D. Thesis OSTS DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor The Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is an equal opportunity employer. DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. LBNL-42162 Two-Dimensional NMR Investigations of the Dynamic Conformations of Phospholipids and Liquid Crystals Mei Hong Ph.D. Thesis Department of Chemistry University of California, Berkeley and Materials Sciences Division Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, CA 94720 May 1996 This work was supported by the Director, Office of Energy Research, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences Division, of the U.S. -

Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies Of

~D 6447 LBNL-42160 ~RNE55T ~lFUANIDC’2 b3A/W?ENK3E Gafmfm a’=-!- 51ERKELXY NIA-T-UEHWQL bd3C3RATClHFW’ Solid-StateNuclearMagnetic ,,,>,, ., -. .-..-... “,,-z,,’>.J ResonanceStudiesof CrossPolarizationlkom QuadrupolarNuclei .- SusanM. De Paul ,. Materials Sciences Division August 1997 . Ph.D. Thesis -. ,.... ,. 0 .. : . .,,,.- ,. ,. .?... ‘I.. ‘.,,.. ---- -... .,. r, .“ ““ . .,.. ,, .,. DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United Statea Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor The Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legaf responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of ~Y information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademmk, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or impIy its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or arty agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of Cafifomia. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of Cafifomia. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley NationaI Laboratory is an equaI opportunity employer. DISCLAIMER Portions -

Phenotypic Impact of Genetic Risk Pathways for Alzheimer's Disease

Phenotypic Impact of Genetic Risk Pathways for Alzheimer’s Disease by Daniel Felsky A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Daniel Felsky 2016 Phenotypic Impact of a Genetic Risk Pathway for Alzheimer’s Disease Daniel Felsky Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The contribution of genetic variation to risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is well-accepted; however, the roles of specific mutations within established risk genes are not clear. Comprehensive datasets with informative in vivo and postmortem biomarkers now offer the opportunity to understand when, where, and how mutations within these genes individually exert their effects on the brain. Moreover, it is known that many of these genes interact at the pathway level, and therefore genetic effects should also be considered in context using gene-gene interaction approaches. I hypothesized that common functional variants modifying established Alzheimer’s risk pathways would demonstrate a) independent effects and b) synergistic effects on human brain structure and other Alzheimer’s biomarkers. First, the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene ε4 allele was found to be associated with white matter integrity in an age-dependent manner. Second, mutations within the sortilin-like receptor (SORL1) gene were associated with differences in white matter integrity, SORL1 gene mRNA expression, and amyloid ii neuropathology that suggested an early genetic risk mechanism beginning as early as childhood. Third, a translocator protein (TSPO) gene variant known to alter TSPO binding characteristics was found to have no direct effects on inflammatory and cerebrovascular brain changes in over 2 300 elderly subjects. -

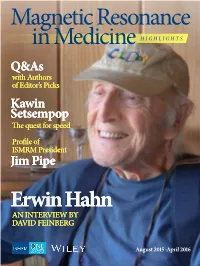

Erwin Hahn an INTERVIEW by DAVID FEINBERG

Magnetic Resonance in Medicine HIGHLIGHTS Q&As with Authors of Editor’s Picks Kawin Setsempop !e quest for speed Pro"le of ISMRM President Jim Pipe Erwin Hahn AN INTERVIEW BY DAVID FEINBERG August 2015-April 2016 COVER STORY !e Transformative Genius of Erwin Hahn INTERVIEW BY David A. Feinberg COVER PHOTO BY Joseph Holmes JOSEPHHOLMES.COM ast summer I had the pleasure of meeting Berkeley professor emeritus, Dr. Erwin L. Hahn. His former (and "nal) graduate student, Larry Wald, was able to connect us in his hometown of Berkeley, LCA. Over a hearty breakfast, Prof. Hahn had accepted my hopeful invitation to give the plenary talk at the upcoming ISMRM work- shop on simultaneous multi-slice imaging. At one point, he asked me what I worked on in MRI and I replied “pulse sequence physics.” He then asked again, “Well, what do you do?” Only later did I realize the naiveté of my ini- tial response. In the days leading up to the workshop I spent many a#ernoons in his house, helping Prof. Hahn "nd and organize his slides for the plenary talk. It was there that I "rst saw in a slide (Fig. 1) his 1949 experiment to measure T1 by incrementally changing the timing be- tween two RF pulses. I came to the realization that this was the very "rst pulse sequence! Erwin Hahn invented pulse sequences! Of course, I knew he discovered the spin echo, but I thought pulse sequences somehow came from the spectroscopy era, like babies from storks. Pulse sequences are a speci"c time-de- pendent series of radio-frequency pulses and magnetic "elds that produce echo signals, and are used to create essentially all imaging methods of MRI. -

Ernest Orlando Lawrence Awards

THE ERNEST ORLANDO LAWRENCE AWARDS JANUARY 19, 2021 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY VIRTUAL CEREMONY HTTPS://scIENCE.OSTI.GOV/LAWRENCE/CEREMONY AN AWARD GIVEN BY THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY WELCOME The Honorable Dan Brouillette, Secretary of Energy welcomes you to the virtual presentation of the ERNEST ORLANDO LAWRENCE AWARD to YI CUI DANIEL KASEN Stanford University and SLAC University of California, National Accelerator Laboratory Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory DANA M. DATTELBAUM Los Alamos National Laboratory ROBERT B. ROSS Argonne National Laboratory DUSTIN H. FROULA University of Rochester SUSANNAH G. TRINGE Lawrence Berkeley National M.ZAHID HASAN Laboratory Princeton University and Lawrence Berkeley National KRISTA S. WALTON Laboratory Georgia Institute of Technology January 19, 2021 United States Department of Energy 1000 Independence Avenue, SW Washington, DC AWARD LAUREATE CITATIONS YI CUI Stanford University and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory ENERGY SCIENCE AND INNOVATION For exceptional contributions in nanomaterials design, synthesis and characterization for energy and the environment, particularly for transformational innovations in battery science and technology. Yi Cui is honored for his insightful introduction of nanosciences in battery research. His multiple innovative ideas have transformed the battery field in a very impactful way and enabled new types of high energy density batteries and low-cost energy storage solutions. Prof. Cui reinvigorated research in batteries by enabling new -

The Transformative Genius of Erwin Hahn INTERVIEW by David A

COVER STORY The transformative genius of Erwin Hahn INTERVIEW BY David A. Feinberg COVER PHOTO BY Joseph Holmes JOSEPHHOLMES.COM ast summer I had the pleasure of meeting Berkeley professor emeritus, Dr. Erwin L. Hahn. His former (and final) graduate student, Larry Wald, was able to connect us in his hometown of Berkeley, LCA. Over a hearty breakfast, Prof. Hahn had accepted my hopeful invitation to give the plenary talk at the upcoming ISMRM work- shop on simultaneous multi-slice imaging. At one point, he asked me what I worked on in MRI and I replied “pulse sequence physics.” He then asked again, “Well, what do you do?” Only later did I realize the naiveté of my ini- tial response. In the days leading up to the workshop I spent many afternoons in his house, helping Prof. Hahn find and organize his slides for the plenary talk. It was there that I first saw in a slide (Fig. 1) his 1949 experiment to measure T1 by incrementally changing the timing be- tween two RF pulses. I came to the realization that this was the very first pulse sequence! Erwin Hahn invented pulse sequences! Of course, I knew he discovered the spin echo, but I thought pulse sequences somehow came from the spectroscopy era, like babies from storks. Pulse sequences are a specific time-de- pendent series of radio-frequency pulses and magnetic fields that produce MR signals, and are used to create essentially all imaging methods of MRI. Erwin Hahn is well-known for the discovery of the spin echo, but a fact often ignored by the MR community is that he was also the first to perform pulsed NMR (the first Free Induction Decay (FID)) and Erwin Hahn’s 2015 lecture at ISMRM Workshop: http://www.ismrm.org/workshops/MultiSlice15/ 2 MAGNETIC RESONANCE IN MEDICINE HIGHLIGHTS | MAY 2016 ISMRM.ORG/MRM to describe the gradient echo.