BIOLOGY 639 SCIENCE ONLINE the Unexpected Brains Behind Blood Vessel Growth 641 THIS WEEK in SCIENCE 668 U.K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parasite Epidemiology and Control

PARASITE EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CONTROL AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 2405-6731 DESCRIPTION . Parasite Epidemiology and Control is an Open Access journal. There is increased parasitology research that analyses the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations. This epidemiology of parasite infectious diseases is predominantly studied in human populations but also includes other major hosts of parasitic infections and as such this journal has broad remit. Parasite Epidemiology and Control focuses on the major areas of epidemiological study including disease etiology, disease surveillance, drug resistance, geographical spread, screening, biomonitoring, and comparisons of treatment effects in clinical trials for both human and other animals. We also focus on the epidemiology and control of vector insects. The journal also covers the use of geographic information systems (Epi-GIS) for epidemiological surveillance which is a rapidly growing area of research in infectious diseases. Molecular epidemiological approaches are also particularly encouraged. ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . PubMed Central Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) Google Scholar ScienceDirect Scopus EDITORIAL BOARD . Founding Editor Marcel Tanner, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland Epidemiology and control, health systems, one-health, global public health Editors Uwemedimo Friday Ekpo, Federal -

Download Issue

Cell Circuitry || Science Teaches English || The Chicken Genome Is Hot || Magnets in Medicine SEPTEMBER 2002 www.hhmi.org/bulletin Leading Doublea Life It’s a stretch, but doctors who work bench to bedside say they wouldn’t do it any other way. FEATURES 14 On Human Terms 24 The Evolutionary War A small—some say too small—group of Efforts to undermine evolution education have physician-scientists believes the best science evolved into a 21st-century marketing cam- requires patient contact. paign that relies on legal acumen, manipulation By Marlene Cimons of scientific literature and grassroots tactics. 20 Engineering the Cell By Trisha Gura Adam Arkin sees the cell as a mechanical system. He hopes to transform molecular 28 Call of the Wild biology into a kind of cellular engineering Could quirky, new animal models help scien- and in the process, learn how to move cells tists learn how to regenerate human limbs or from sickness to health. avert the debilitating effects of a stroke? By M. Mitchell Waldrop By Kathryn Brown 24 In front of a crowd of 1,500, Ohio’s Board of Education heard testimony on whether students should learn about intelligent design in science class. DEPARTMENTS 2 NOTA BENE 33 PERSPECTIVE ulletin Intelligent Design Is a Cop-Out 4 LETTERS September 2002 || Volume 15 Number 3 NEWS AND NOTES HHMI TRUSTEES PRESIDENT’S LETTER 5 JAMES A. BAKER, III, ESQ. 34 Senior Partner, Baker & Botts A Creative Influence In from the Fields ALEXANDER G. BEARN, M.D. Executive Officer, American Philosophical Society 35 Lost on the Tip of the Tongue Adjunct Professor, The Rockefeller University UP FRONT Professor Emeritus of Medicine, Cornell University Medical College 36 Biology by Numbers FRANK WILLIAM GAY 6 Follow the Songbird Former President and Chief Executive Officer, SUMMA Corporation JAMES H. -

The Pharmacologist 2 0 0 6 December

Vol. 48 Number 4 The Pharmacologist 2 0 0 6 December 2006 YEAR IN REVIEW The Presidential Torch is passed from James E. Experimental Biology 2006 in San Francisco Barrett to Elaine Sanders-Bush ASPET Members attend the 15th World Congress in China Young Scientists at EB 2006 ASPET Awards Winners at EB 2006 Inside this Issue: ASPET Election Online EB ’07 Program Grid Neuropharmacology Division Mixer at SFN 2006 New England Chapter Meeting Summary SEPS Meeting Summary and Abstracts MAPS Meeting Summary and Abstracts Call for Late-Breaking Abstracts for EB‘07 A Publication of the American Society for 121 Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics - ASPET Volume 48 Number 4, 2006 The Pharmacologist is published and distributed by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. The Editor PHARMACOLOGIST Suzie Thompson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bryan F. Cox, Ph.D. News Ronald N. Hines, Ph.D. Terrence J. Monks, Ph.D. 2006 Year in Review page 123 COUNCIL . President Contributors for 2006 . page 124 Elaine Sanders-Bush, Ph.D. Election 2007 . President-Elect page 126 Kenneth P. Minneman, Ph.D. EB 2007 Program Grid . page 130 Past President James E. Barrett, Ph.D. Features Secretary/Treasurer Lynn Wecker, Ph.D. Secretary/Treasurer-Elect Journals . Annette E. Fleckenstein, Ph.D. page 132 Past Secretary/Treasurer Public Affairs & Government Relations . page 134 Patricia K. Sonsalla, Ph.D. Division News Councilors Bryan F. Cox, Ph.D. Division for Neuropharmacology . page 136 Ronald N. Hines, Ph.D. Centennial Update . Terrence J. Monks, Ph.D. page 137 Chair, Board of Publications Trustees Members in the News . -

Mothers in Science

The aim of this book is to illustrate, graphically, that it is perfectly possible to combine a successful and fulfilling career in research science with motherhood, and that there are no rules about how to do this. On each page you will find a timeline showing on one side, the career path of a research group leader in academic science, and on the other side, important events in her family life. Each contributor has also provided a brief text about their research and about how they have combined their career and family commitments. This project was funded by a Rosalind Franklin Award from the Royal Society 1 Foreword It is well known that women are under-represented in careers in These rules are part of a much wider mythology among scientists of science. In academia, considerable attention has been focused on the both genders at the PhD and post-doctoral stages in their careers. paucity of women at lecturer level, and the even more lamentable The myths bubble up from the combination of two aspects of the state of affairs at more senior levels. The academic career path has academic science environment. First, a quick look at the numbers a long apprenticeship. Typically there is an undergraduate degree, immediately shows that there are far fewer lectureship positions followed by a PhD, then some post-doctoral research contracts and than qualified candidates to fill them. Second, the mentors of early research fellowships, and then finally a more stable lectureship or career researchers are academic scientists who have successfully permanent research leader position, with promotion on up the made the transition to lectureships and beyond. -

Female Fellows of the Royal Society

Female Fellows of the Royal Society Professor Jan Anderson FRS [1996] Professor Ruth Lynden-Bell FRS [2006] Professor Judith Armitage FRS [2013] Dr Mary Lyon FRS [1973] Professor Frances Ashcroft FMedSci FRS [1999] Professor Georgina Mace CBE FRS [2002] Professor Gillian Bates FMedSci FRS [2007] Professor Trudy Mackay FRS [2006] Professor Jean Beggs CBE FRS [1998] Professor Enid MacRobbie FRS [1991] Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell DBE FRS [2003] Dr Philippa Marrack FMedSci FRS [1997] Dame Valerie Beral DBE FMedSci FRS [2006] Professor Dusa McDuff FRS [1994] Dr Mariann Bienz FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Angela McLean FRS [2009] Professor Elizabeth Blackburn AC FRS [1992] Professor Anne Mills FMedSci FRS [2013] Professor Andrea Brand FMedSci FRS [2010] Professor Brenda Milner CC FRS [1979] Professor Eleanor Burbidge FRS [1964] Dr Anne O'Garra FMedSci FRS [2008] Professor Eleanor Campbell FRS [2010] Dame Bridget Ogilvie AC DBE FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Doreen Cantrell FMedSci FRS [2011] Baroness Onora O'Neill * CBE FBA FMedSci FRS [2007] Professor Lorna Casselton CBE FRS [1999] Dame Linda Partridge DBE FMedSci FRS [1996] Professor Deborah Charlesworth FRS [2005] Dr Barbara Pearse FRS [1988] Professor Jennifer Clack FRS [2009] Professor Fiona Powrie FRS [2011] Professor Nicola Clayton FRS [2010] Professor Susan Rees FRS [2002] Professor Suzanne Cory AC FRS [1992] Professor Daniela Rhodes FRS [2007] Dame Kay Davies DBE FMedSci FRS [2003] Professor Elizabeth Robertson FRS [2003] Professor Caroline Dean OBE FRS [2004] Dame Carol Robinson DBE FMedSci -

Section 1: MIT Facts and History

1 MIT Facts and History Economic Information 9 Technology Licensing Office 9 People 9 Students 10 Undergraduate Students 11 Graduate Students 12 Degrees 13 Alumni 13 Postdoctoral Appointments 14 Faculty and Staff 15 Awards and Honors of Current Faculty and Staff 16 Awards Highlights 17 Fields of Study 18 Research Laboratories, Centers, and Programs 19 Academic and Research Affiliations 20 Education Highlights 23 Research Highlights 26 7 MIT Facts and History The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is one nologies for artificial limbs, and the magnetic core of the world’s preeminent research universities, memory that enabled the development of digital dedicated to advancing knowledge and educating computers. Exciting areas of research and education students in science, technology, and other areas of today include neuroscience and the study of the scholarship that will best serve the nation and the brain and mind, bioengineering, energy, the envi- world. It is known for rigorous academic programs, ronment and sustainable development, informa- cutting-edge research, a diverse campus commu- tion sciences and technology, new media, financial nity, and its long-standing commitment to working technology, and entrepreneurship. with the public and private sectors to bring new knowledge to bear on the world’s great challenges. University research is one of the mainsprings of growth in an economy that is increasingly defined William Barton Rogers, the Institute’s founding pres- by technology. A study released in February 2009 ident, believed that education should be both broad by the Kauffman Foundation estimates that MIT and useful, enabling students to participate in “the graduates had founded 25,800 active companies. -

Sten Grillner

BK-SFN-HON_V9-160105-Grillner.indd 108 5/6/2016 4:11:20 PM Sten Grillner BORN: Stockholm, Sweden June 14, 1941 EDUCATION: University of Göteborg, Sweden, Med. Candidate (1962) University of Göteborg, Sweden, Dr. of Medicine, PhD (1969) Academy of Science, Moscow, Visiting Scientist (1971) APPOINTMENTS: Docent in Physiology, Medical Faculty, University of Göteborg (1969–1975) Professor, Department of Physiology III, Karolinska Institute (1975–1986) Director, Nobel Institute for Neurophysiology, Karolinska Institute, Professor (1987) Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, Chair, 1995–1997 (1987–1998) Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institutet, Member Chair, 2005 (1988–2008) Chairman Department of Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet (1993–2000) Distinguished Professor, Karolinska Institutet (2010) HONORS AND AWARDS: Member of Academiae Europaea 1990– Member of Royal Swedish Academy of Science 1993– Chairman Section for Biology and Member of Academy Board, 2004–2010 Member of Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, 1997– Member American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2004– Honorary Member of the Spanish Medical Academy, 2006– Foreign Associate of Institute of Medicine of the National Academy, United States, 2006– Foreign Associate of the National Academy, United States, 2010– Associate of the Neuroscience Institute, La Jolla, 1989– Member EMBO, 2014– Florman Award, Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 1977 Grass Lecturer to the Society of Neuroscience, Boston, 1983 Greater Nordic Prize of Eric Fernstrom, Lund, Sweden, 1990 Bristol-Myers -

2018 March Meeting Program Guide

MARCHMEETING2018 LOS ANGELES MARCH 5-9 PROGRAM GUIDE #apsmarch aps.org/meetingapp aps.org/meetings/march Senior Editor: Arup Chakraborty Robert T. Haslam Professor of Chemical Engineering; Professor of Chemistry, Physics, and Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, MIT Now welcoming submissions in the Physics of Living Systems Submit your best work at elifesci.org/physics-living-systems Image: D. Bonazzi (CC BY 2.0) Led by Senior Editor Arup Chakraborty, this dedicated new section of the open-access journal eLife welcomes studies in which experimental, theoretical, and computational approaches rooted in the physical sciences are developed and/or applied to provide deep insights into the collective properties and function of multicomponent biological systems and processes. eLife publishes groundbreaking research in the life and biomedical sciences. All decisions are made by working scientists. WELCOME t is a pleasure to welcome you to Los Angeles and to the APS March I Meeting 2018. As has become a tradition, the March Meeting is a spectacular gathering of an enthusiastic group of scientists from diverse organizations and backgrounds who have broad interests in physics. This meeting provides us an opportunity to present exciting new work as well as to learn from others, and to meet up with colleagues and make new friends. While you are here, I encourage you to take every opportunity to experience the amazing science that envelops us at the meeting, and to enjoy the many additional professional and social gatherings offered. Additionally, this is a year for Strategic Planning for APS, when the membership will consider the evolving mission of APS and where we want to go as a society. -

Sumoylation Regulates Protein Dynamics During Meiotic Chromosome Segregation in C

© 2019. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2019) 132, jcs232330. doi:10.1242/jcs.232330 RESEARCH ARTICLE Sumoylation regulates protein dynamics during meiotic chromosome segregation in C. elegans oocytes Federico Pelisch*, Laura Bel Borja, Ellis G. Jaffray and Ronald T. Hay ABSTRACT studies of MT-dependent chromosome movement focused on Oocyte meiotic spindles in most species lack centrosomes and pulling forces generated by kinetochore MTs (kMTs) making the mechanisms that underlie faithful chromosome segregation end-on contacts with chromosomes (Cheeseman, 2014), there is in acentrosomal meiotic spindles are not well understood. In also evidence for pushing forces that are exerted on the segregating C. elegans oocytes, spindle microtubules exert a poleward force on chromosomes (Khodjakov et al., 2004; Nahaboo et al., 2015; š ́ chromosomes that is dependent on the microtubule-stabilising Laband et al., 2017; Vuku ic et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2019 preprint). protein CLS-2, the orthologue of the mammalian CLASP proteins. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans contains holocentric The checkpoint kinase BUB-1 and CLS-2 localise in the central chromosomes (Maddox et al., 2004) and has served as an spindle and display a dynamic localisation pattern throughout extremely useful system to uncover mechanisms of meiosis and anaphase, but the signals regulating their anaphase-specific mitosis for almost 20 years (Oegema et al., 2001; Desai et al., 2003; localisation remains unknown. We have shown previously that Cheeseman et al., 2004, 2005; Monen et al., 2005). Meiosis is a SUMO regulates BUB-1 localisation during metaphase I. Here, we specialised cell division with two successive rounds of chromosome found that SUMO modification of BUB-1 is regulated by the SUMO E3 segregation that reduce the ploidy and generates haploid gametes ligase GEI-17 and the SUMO protease ULP-1. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Awards and Honours: April 2019

AWARDS AND HONOURS: APRIL 2019 Name Category Organized/ Presented by PM Narendra Modi Russian Award “Order of Saint Russia Andrew The Apostle” Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Nobel International Human Rights Sunny Shah(Founder of International Council Award Human Rights Council) K Siva Reddy Prestigious Saraswati Samman KK Birla Foundation 2018 Dr. A K Singh Lifetime Achievement Award University to mark World Creativity and Innovation Day Bhayanakam (Malayalam film) Best Cinematography Award Beijing International Film Festival Benny Antony National Intellectual Property Intellectual Property Office India and Award for 2019. the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) Author Rana Dasgupta Rabindranath Tagore Literary -- Prize 2019 All India Radio and Children's Film Swacchta Pakhwada Award Secretary in the Information and Society of India. Broadcasting Ministry Amit Khare Dr Rajendra Joshi Pravasi Bhartiya Samman Award Indian Ambassador to Switzerland Sibi George Lewis Hamilton Bahrain Grand Prix 2019 title Bahrain Grand Prix Vikram Patel John Dirks Canada Gairdner -- Global Health Award. PM Narendra Modi Zayed Medal President of the UAE Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan Shah Rukh Khan Honorary doctorate in University of Law, London Philanthropy Dr Sohini Sastri 'D. Litt in Astrology' Award National American University, USA. Tata Steel 'Global Slag Company of the Germany Year' Award Jacques Kallis Order of Ikhamanga in the Silver President of South Africa Division Deepa Malik New Zealand Prime Minister’s Sir New Zealand Edmund Hillary Fellowship for 2019 'Dost Education' $25,000 Next Billion Edtech Prize UK-based Varkey Foundation 2019 National Mission for Clean ‘Public Water Agency of the Year’ Global Water Intelligence at the Global www.BankExamsToday.com Page 1 Ganga(NMCG) or Namami Gange award Water Summit in London. -

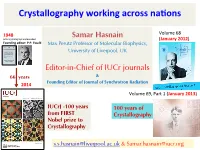

Samar Hasnain

Crystallography,working,across,na2ons, , 1948, Samar Hasnain Volume!68! Acta!Crystallographica!launched! (January,2012)! Founding,editor:,P.P.,Ewald, Max Perutz Professor of Molecular Biophysics, University of Liverpool, UK Editor-in-Chief of IUCr journals 66 years ! & Founding Editor of Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2014, Volume!69,!Part!1!(January,2013)! IUCrJ -100 years 100 years of from FIRST Crystallography, Nobel prize to Crystallography, [email protected] & [email protected]! IUCr facts 53#member!countries! 42#Adhering!Bodies!(including!4 Regional!Associates:!ACA,!AsCA,!ECA,!LACA)! 23#Commissions! 9#Journals!(including#IUCrJ#launched!in!2014)! IUCr!Congress!every!3#years!(24th IUCr!Congress,!Hyderabad,!August!2017)! Michele Zema The IUCr is a member of since 1947 Project Manager for IYCr2014 EMC5, Oujda, Oct 2013 IUCr Journal milestones 1968, Acta!Crystallographica!split!into!! 1948, SecMon!A:!FoundaMons!of!! Acta!Crystallographica!launched! Crystallography!and!SecMon!B:!! Founding,editor:,P.P.,Ewald, Structural!Science! Founding,editor:,A.J.C.,Wilson, ! 1983, 1968, Acta!Crystallographica!SecMon!C:!! Journal!of!Applied!Crystallography! Crystal!Structure!CommunicaMons!! 1991, launched! Adop2on,of,CIF, launched! Founding,editor:,A.,Guinier, Founding,editor:,S.C.,Abrahams, ! ! 1994, 1993, Journal!of!Synchrotron!! Acta!Crystallographica!SecMon!D:!! RadiaMon!launched! 1999, Biological!Crystallography! Founding,editors:,, Online,, launched! S.S.,Hasnain,,J.R.,Helliwell,, access, Founding,editor:,J.P.,Glusker, and,H.,Kamitsubo,