VINCENT BOUSSARD a Look Back on a Journey of Human and Artistic Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

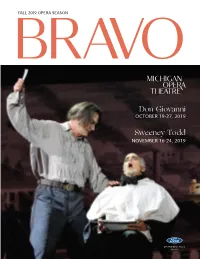

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Takte 1-09.Pmd

[t]akte Das Bärenreiter-Magazin Wundersame Mischungen Ernst und komisch zugleich: Haydns „La fedeltà premiata” 1I2009 Das geheime Leben Informationen für Miroslav Srnka auf Entdeckungstour Bühne und Orchester Plädoyer für ein großartiges Repertoire Marc Minkowski über die französische Oper des 19. Jahrhunderts [t]akte 481018 „Unheilvolle Aktualität“ Abendzauber Das geheime Leben Telemann in Hamburg Ján Cikkers Opernschaffen Neue Werke von Thomas Miroslav Srnka begibt sich auf Zwei geschichtsträchtige Daniel Schlee Entdeckungstour Richtung Opern in Neueditionen Die Werke des slowakischen Stimme Komponisten J n Cikker (1911– Für Konstanz, Wien und Stutt- Am Hamburger Gänsemarkt 1989) wurden diesseits und gart komponiert Thomas Miroslav Srnka ist Förderpreis- feierte Telemann mit „Der Sieg jenseits des Eisernen Vorhangs Daniel Schlee drei gewichtige träger der Ernst von Siemens der Schönheit“ seinen erfolg- aufgeführt. Der 20. Todestag neue Werke: ein Klavierkon- Musikstiftung 2009. Bei der reichen Einstand, an den er bietet den Anlass zu einer neu- zert, das Ensemblestück „En- Preisverleihung im Mai wird wenig später mit seiner en Betrachtung seines um- chantement vespéral“ und eine Komposition für Blechblä- Händel-Adaption „Richardus I.“ fangreichen Opernschaffens. schließlich „Spes unica“ für ser und Schlagzeug uraufge- anknüpfen konnte. Verwickelte großes Orchester. Ein Inter- führt. Darüber hinaus arbeitet Liebesgeschichten waren view mit dem Komponisten. er an einer Kammeroper nach damals beliebt, egal ob sie im Isabel Coixets Film -

Vincent B Oussard

V I N C E N T B O U S S A R D – Stage Director After his debut as a stage director at the Studio Theatre of the Comédie-Française, Vincent Boussard devoted himself to opera-staging since 2001. Since then he has staged more than 40 different opera, from Cavalli, Mozart and Bellini to French Grand Opéra, Wagner, Puccini, up to Kurt Weill and contemporary composers. He has worked for some the world leading companies including Salzburg Easter Festival, Opéra Royal de La Monnaie de Bruxelles, Opéra National du Rhin, Opéra de Marseille, Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse, Aix-en-Provence Festival, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Frankfurt Opera, Staatsoper Hamburg, Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, Gran Teatre del Liceu de Barcelona, Kungliga Operan in Stockholm, Theater an der Wien, San Francisco Opera, New National Theatre in Tokyo, Korea National Opera in Seoul, Innsbruck Festival, Festival dei Due Mondi in Spoleto and many others. He has already worked with such conductors as Christian Thielemann, Daniel Harding, Yves Abel, Rinaldo Alessandrini, Lionel Bringuier, Riccardo Frizza, Alexander Joel, Andreas Spering, René Jacobs and William Christie, among others. Some of his productions have been TV-broadcasted and released on DVD: Don Giovanni, Dido & Aeneas, Frühlingserwachen (awarded “Diapason d’or“), I Capuleti e i Montecchi, La Favorite, Madama Butterfly, Un Ballo in Maschera and Otello. Among his most important productions, it can be mentioned Otello (conductor Christian Thielemann) at Easter Festival in Salzburg and at Semperoper Dresden, Haendel’s Agrippina and Bernstein’s Candide at Staatsoper Berlin, I Capuleti e I Montecchi at Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, Carmen at Kungliga Operan in Stockholm, Madama Butterfly and La fanciulla del West at Staatsoper Hamburg, Così fan tutte, Cavalli’s Eliogabalo and Cimarosa’s Il matrimonio segreto at La Monnaie in Brussels, Le nozze di Figaro at Festival International d'Art Lyrique d'Aix en Provence. -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

Avi Shoshani Temporadas De Ópera Anne-Sophie Mutter Riccardo Muti

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXVI - Nº 267 - Octubre 2011 - 7 € DOSIER Temporadas de ópera ENCUENTROS Avi Shoshani ACTUALIDAD Anne-Sophie Mutter Riccardo Muti ESTUDIO El estado de las orquestas REFerencias Iberia de Debussy Año XXVI - Nº 267 Octubre 2011 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K OCTUBRE ENERO 01 Los caminos del mundo 06 Fronteras abolidas 11 Poemas sin palabras E. Rautavaara: Cantus Arcticus M. Finnissy: Zortziko S. Rachmaninov: Rapsodia M. Ravel: Concierto para piano (estreno absoluto, encargo sobre un tema de Paganini es y orquesta en sol mayor OSE) R. Strauss: Muerte y J. Haydn: Sinfonía nº67 A. Dorman: Frozen in Time transfiguración B. Bartok: El Mandarín J. Brahms: Sinfonía nº4 R. Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel tiempo Maravilloso (suite) Martin Grübinger, percusión Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Alice Sara Ott, piano Andrés Orozco-Estrada, director de Andrey Boreyko, director director Joaquín Achúcarro, piano 02 Mendelssohniana ENERO-FEBRERO MAYO música F. Mendelssohn: Sinfonía nº1 07 Clásicos y modernos 12 Nostalgias compartidas P.I. Tchaikovsky: Variaciones rococó J. Dillon: White Numbers A. Dvorák: Concierto para F. Mendelssohn: Sinfonía nº4 (estreno absoluto, encargo violoncello y orquesta OSE) I. Fedele: Txalaparta-Folk Gabriel Mesado, violoncello E. Schulhoff: Sinfonía nº2 Dance II (estreno absoluto, (miembro OSE) A. Zemlinsky: Cymbeline encargo OSE) Andrés Orozco-Estrada, director L.V. Beethoven: Sinfonía nº3 C. Franck: Psyché Orquesta F. Mendelssohn: Sinfonía nº5 Petra Fröse, soprano Daniel Müller-Schott, violoncello Dos estudios de concierto para Gerd Albrecht, director Oreka TX Sinfónica clarinete, corno di bassetto y Andrey Boreyko, director orquesta MARZO de Euskadi Sinfonía nº3 MAYO-JUNIO Juan Navarro, clarinete 08 Viñetas del Euskadiko (miembro OSE) Nuevo Mundo 13 En el calor de la noche Sara Zufiaurre, corno di A. -

Newsletter • Bulletin Summer 2007 Été 2007

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIÉTÉ D'OPÉRA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Summer 2007 Été 2007 P.O. Box 8347, Main Terminal, Ottawa, Ontario K1G 3H8 • C.P. 8347, Succursale principale, Ottawa (Ontario) K1G 3H8 Cabellissima! by Shelagh Williams Cathedral Arts has done it again and brought us another su- ing! Bernstein’s I Hate Music, a song cycle of “Five Kid perb opera singer, American lyric soprano Nicole Cabell, to- Songs”, was sung with suitable actions and wide-eyed won- gether with Scottish pianist Alan Darling for a recital of opera der, in a most entertaining manner. Among the other offer- arias and art songs. Having won the 2005 BBC Cardiff ings, she really shimmered in William Bolcom’s “Amore”, Singer of the World Competition she has been showered and then after Kurt Weill's heartfelt “What good would the with accolades but one is still not really prepared for Nicole moon be” from Street Scene, closed with “And this is my Cabell in person — she has the voice, the looks, the pres- Beloved” from Kismet. ence, the whole package! This performance of superb technique and The first half of the programme was framed by well- beautiful tone elicited a rousing standing ovation which known arias from Nicole’s operatic rep- was rewarded with an encore of ertoire. Each aria benefited from her hav- “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess. ing performed the associated roles and her This was an excellent concert and a ability to use her mobile, expressive face rare chance to hear such an outstand- to convey the emotions involved. -

Lawrence Brownlee and Eric Owens Craig Terry, Piano Friday, March 8, 2019 7:30 Pm Photo: © Dario Acosta © Dario Photo

Photo: Shervin Lainez Photo: Lawrence Brownlee and Eric Owens Craig Terry, Piano Friday, March 8, 2019 7:30 pm Photo: © Dario Acosta © Dario Photo: 2018/2019 SEASON Great Artists. Great Audiences. Hancher Performances. LAWRENCE BROWNLEE, TENOR ERIC OWENS, BASS-BARITONE CRAIG TERRY, PIANO Friday, March 8, 2019, at 7:30 pm Hancher Auditorium, The University of Iowa PROGRAM “Se vuol ballare,” from Le Nozze di Figaro Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Eric Owens “Il mio tesoro,” from Don Giovanni Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Lawrence Brownlee “Infelice! E tuo credevi,” from Ernani Giuseppe Verdi Eric Owens “Voglio dire, lo stupendo elisir,” from L'elisir d'amore Gaetano Donizetti Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens “Una furtiva lagrima,” from L'elisir d'amore Gaetano Donizetti Lawrence Brownlee “Le veau d'or,” from Faust Charles Gounod Eric Owens “Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête!,” from La fille du regiment Gaetano Donizetti Lawrence Brownlee “Au fond du temple saint,” from Les Pêcheurs de Perles Georges Bizet Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens INTERMISSION Traditional Spirituals “All Night, All Day” arr. Damien Sneed Lawrence Brownlee “Deep River” arr. Hall Johnson Eric Owens “Come By Here, Good Lord” arr. Damien Sneed Lawrence Brownlee “Give Me Jesus” Traditional Eric Owens “He's Got the Whole World In His Hand” arr. Margaret Bonds / Craig Terry Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens American Popular Songs “Song of Songs” Harold Vicars and Clarence Lucas Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens arr. Craig Terry “Lulu's Back In Town” Harry Warren and Al Dubin Lawrence Brownlee arr. Craig Terry “Dolores” Frank Loesser and Louis Alter Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens arr. Craig Terry “Some Enchanted Evening,” from South Pacific Richard Rodgers Eric Owens & Oscar Hammerstein II “Through the Years” Vincent Youmans and Edward Heyman Lawrence Brownlee, Eric Owens arr. -

San Francisco Opera 2021-22 Season Announcement Updated 8.13.21.Pdf

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA RETURNS TO THE WAR MEMORIAL OPERA HOUSE STAGE Eun Sun Kim Opens 2021–22 Season and Music Directorship Tenure with Puccini’s Tosca Starring Ailyn Pérez, Michael Fabiano and Alfred Walker Eun Sun Kim (Photos: Marc Olivier Le Blanc; Daniel Delang) Kim Leads Beethoven’s Fidelio in a Bold New Production by Director Matthew Ozawa Featuring Elza van den Heever and Russell Thomas Along with Homecoming Concert, Adler Fellows Concert and Verdi Tribute Company’s Multi-Year Mozart-Da Ponte Trilogy Continues with New Productions of Così fan tutte and Don Giovanni Set in Different Eras of an American House Season Highlights Also Include Bright Sheng and David Henry Hwang’s Dream of the Red Chamber, Livestreaming, Free Opera at the Ballpark Simulcast Tickets Now on Sale – Visit sfopera.com or call (415) 864-3330 Puccini’s Tosca; Beethoven’s Fidelio set rendering by Alexander V. Nichols; Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber (Photos: Cory Weaver) 1 San Francisco, CA (June 22, 2021; updated August 13, 2021) — San Francisco Opera announced today repertory, casting and reopening plans for its 99th season. Commencing with a performance of Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca on Saturday, August 21, the 2021–22 Season marks the inauguration of Eun Sun Kim’s tenure as Caroline H. Hume Music Director and a reemergence of opera at the War Memorial Opera House, which reopens with newly installed custom seats and accessibility enhancements. For this transitional year, the Company unveils three new productions: Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fidelio and, continuing the Company’s Mozart-Da Ponte Trilogy, Così fan tutte and Don Giovanni. -

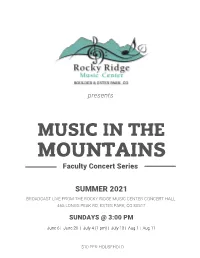

Music in the Mountains: Faculty Concert Series Program 1

presents MUSIC IN THE MOUNTAINS Faculty Concert Series SUMMER 2021 BROADCAST LIVE FROM THE ROCKY RIDGE MUSIC CENTER CONCERT HALL 465 LONGS PEAK RD, ESTES PARK, CO 80517 SUNDAYS @ 3:00 PM June 6 | June 20 | July 4 (1 pm) | July 18 | Aug 1 | Aug 11 $10 PER HOUSEHOLD JUNE 6, 2021 Young Artist Seminar Faculty Intrada for Horn Solo Otto Ketting (b. 1935) John McGuire, horn Impromptu No. 1 in Ab Major, Op. 29 Frédéric Chopin (1810-1847) Impromptu No. 2 in F# Major, Op. 36 Spencer Myer, piano Pirin for Solo Viola (2000) Dobrinka Tabakova (b. 1980) David Rose, viola Summerland William Grant Still (1895-1978) Claudia Anderson, flute Andrew Campbell, piano Kegelstatt Trio for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) I. Andante III. Rondeaux: Allegretto David Shea, clarinet David Rose, viola Spencer Myer, piano Trio for Flute, Clarinet, and Bassoon Op. 61, No. 5 in Bb Major François Devienne (1759-1803) I. Allegro arr. Gyorgy Balassa Valerie Coleman Rubispheres for Flute, Clarinet, and Bassoon (2015) III. Revival Claudia Anderson, flute David Shea, clarinet Rémy Taghavi, bassoon FACULTY BIOS Claudia Anderson Claudia Anderson is known for her originality and brilliance as a solo and chamber music performer across the U.S. She is a founding member of the innovative flute duo ZAWA! and of New Prairie Camerata, a chamber initiative that showcases a community’s historical and architectural gems through performance and stimulates community participation. A Fulbright scholar to Italy, Ms. Anderson was subsequently principal flute of the Orchestra del Teatro Massimo in Palermo. She is presently principal flute with the Waterloo/Cedar Falls Symphony in Iowa, a guest artist and clinician at many colleges and music series around the country, and on the faculty of Grinnell College. -

M O N T E V E R

MONTEVERDI Music is the servant of the words 2012 LET US INNOVATE by Simone Kotva FROM IMITATION OF NATURE MONTEVERDI’S REVERSAL TO NATURAL IMITATION At the turn of the sixteenth century, the cusp of Monteverdi christened his musical aesthetics the We should see what are the rhythms of a self- The sentence immediately preceding Plato’s antici - what historians have since called “the modern era,” seconda prattica , or Second Practice. Its purpose disciplined and courageous life, and after looking at pation of Monteverdi’s motto is a discussion of the Claudio Monteverdi poses the perennial question was to oppose the establishment, what he called those, make meter and melody conform to the leitmotif of Classical philosophy, namely the “self- of every artist: how do my compositions relate to the First Practice of music theory. Monteverdi speech of someone like that. We won’t make disciplined and courageous life,” or human nature. those of past masters? How does innovation characterised the First Practice (whether justly or speech conform to rhythm and melody . Plato’s belief (which was also Aristotle’s) was that relate to imitation? not), as concerned exclusively with the rules of (Republic 400a; my emphasis) human nature was formed through a life-long pro - “pure” harmony stripped of any relation to text, cess of cultivating good habits. These good habits For Monteverdi, living in a time of vitriolic polemics rhythm and melody. It philosophical foundations The final sentence mirrors the emphatic declara - would eventually lead to good virtues, -

Cubierta SEPTIEMBRE 2012 .Indd

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXVII - Nº 277 - Septiembre 2012 - 7 € Año XXVII - Nº 277 Septiembre 2012 DOSIER Orquestas españolas 2012-2013 ENTREVISTA Véronique Gens ACTUALIDAD Oliver Knussen AGENDA La nueva temporada REFERENCIAS Primer Razumovski de Beethoven Centro Nacional de Difusión Musical VOCES CECILIA BARTOLI • RAqUEL ANDUEZA • EUT LEMPER • ANNA CATERINA ANTONACCI • MatthIAS GOERNE • DAVID DANIELS • VIVICA GENAUX • MAESTROS BARROCOS GIOVANNI ANTONINI • FABIO BIONDI • ALAN CURTIS • ChristophER hOGWOOD • EDUARDO LÓPEZ BANZO • RENé JACOBS • ChristophE ROUSSET • JORDI SAVALL • SOLISTAS VIktoria MULLOVA • LLUÍS CLARET • PIERRE hANTAÏ • ISABELLE FAUST • ELISABETh LEONSkAJA • MARkUS STOCkhAUSEN • MIChAEL NYMAN • JAZZ Y FLAMENCO MALIA • VIJAY IYER TRIO • ATOMIC • ChICk COREA • MIChEL CAMILO & TOMATITO • EL CIGALA • MARÍA TOLEDO • DORANTES • CAÑIZARES • MANUEL LOMBO • ARCÁNGEL • M ARINA hEREDIA • CONJUNTOS INTERNACIONALES AL AYRE ESPAÑOL • LES ARTS FLORISSANTS • IL GIARDINO ARMONICO • EUROPA GALANTE • hESPÈRION XXI • LES TALENS LYRIqUES • IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO • FREIBURGER BAROCkORChESTER • ThE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC • CUARTETOS BRODSkY • kRONOS • JERUSALéN • LEIPZIG • TOkIO... AUDITORIO NACIONAL DE MÚSICA LOCALIDADES TEATRO DE LA ZARZUELA PÚBLICO GENERAL DESDE 7 € ENTRADAS ÚLTIMO MINUTO MUSEO REINA SOFÍA (MENORES DE 26 AÑOS) DESDE 2,80 € www.cndm.mcu.es Venta desde el 06/09 en las taquillas del Auditorio Nacional de Música, taquillas de los teatros del INAEM y en www.cndm.mcu.es Pantone 186c cmyk 100/81/0/4 pantone: 258C | cmyk 42/84/5/1 Gen2Sch.indd -

SIR ANDREW DAVIS Music Director and Principal Conductor, Lyric Opera of Chicago

SIR ANDREW DAVIS Music Director and Principal Conductor, Lyric Opera of Chicago Biography (Full Version) Sir Andrew Davis has served as music director and principal conductor of Lyric Opera of Chicago since 2000. His contract with Lyric Opera was recently extended through the 2020-2021 season. In January 2013 Sir Andrew began his tenure as chief conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. He is also conductor laureate of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (having previously served as principal conductor), conductor laureate of the BBC Symphony Orchestra (his tenure as that ensemble’s chief conductor was the longest since that of its founder Sir Adrian Boult) and former music director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera. The English conductor begins his 2014-2015 season at Lyric Opera for the company’s new production of Don Giovanni , as well as Strauss’s Capriccio. Following Lyric Opera’s 60th Anniversary Diamond Gala, Sir Andrew heads to the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra for a series of concerts, and then to the Metropolitan Opera to conduct Hansel und Gretel and a new production of The Merry Widow directed by Susan Stroman. In the New Year, Sir Andrew returns to Lyric Opera to conduct the monumental Tannhauser, and Lyric’s presentation of David Pountney’s production of Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s The Passenger. The rest of the 2014-2015 season includes returns to Melbourne for the continuation of Sir Andrew’s exploration of all the Mahler Symphonies with the MSO as well as performances of Britten’s War Requiem, and engagements with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the BBC Philharmonic, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, The Toronto Symphony (Verdi’s Requiem), and performances with the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Three Choirs Festival.