M O N T E V E R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rádio, Ditadura E Rock Radio, Dictatorship and Rock

Rádio, ditadura e rock 2 Sergio Ricardo Quiroga 2 6 Como citar este artigo: QUIROGA, Sergio Ricardo. Radio, Dictatorship and rock. Revista Rádio-Leituras, Mariana-MG, v. 07, n. 01, pp. 226-241, jan./jun. 2016. Radio, Dictatorship and rock Sergio Ricardo Quiroga1 Recebido em: 02 de fevereiro de 2016. Aprovado em: 11 de junho de 2016. Resumo Este artigo descreve o desempenho de dois programas de rádio na Rádio LV 15 Rádio Villa Mercedes, San Luís, Argentina, em 1982-1983, os dois últimos anos de um período triste da história da Argentina chamado "Processo de Reorganização Nacional" entre 1976 e 1983. Os programas "Pessoas jovens" e “LV Amizade”, emitidos pela LV 15 Rádio Villa Mercedes (S.L.), aos sábados, durante 1982 e 1983 e foram dedicados à juventude. Após a Guerra das Malvinas e a proibição de radiodifusão argentina na música estrangeira, os clássicos esquecidos do rock argentino começaram a formar o ingrediente principal do programa. Anteriormente, a ditadura militar reprimiu toda a atividade política, instalando as "listas de artistas proibidos" que não podiam ser divulgados através da mídia. Palavras-chave: rádio; rock; ditadura 1 Cátedra Libre Pensamiento Comunicacional Latinoamericano - ICAES. Integrante colaborador Proyecto Cambios y Tensiones en la Universidad Argentina en el marco del centenario de la Reforma de 1918. Vol 7, Num 01 Edição Janeiro – Junho 2016 ISSN: 2179-6033 http://www.periodicos.ufop.br/pp/index.php/radio-leituras Abstract This paper describes the performance of two radio programs on Radio LV 15 Radio Villa Mercedes, San Luis, Argentina, in 1982-1983, the last two years of a sad period in Argentina's history called "National Reorganization Process" between 1976 and 1983. -

Del 26-2 Al 4-3.Qxp

Del 26 de febrero al 4 de marzo de 2009 VERANO 09 En el último fin de semana de “Aires CUATRO GRANDES Buenos Aires. Cultura para Respirar”, la Ciudad propone para este sábado cuatro grandes recitales gratuitos: La MOMENTOS Portuaria en Costanera Sur, Jairo cantando a Horacio Ferrer en Mataderos; Café de los Maestros, en el Planetario, y el enorme cantaor Enrique Morente en Avenida de Mayo y Perú. PÁGINAS 4, 5, 6 Y 7. sumario. Fin de fiesta [pág. 3] El cantaor granadino [pág.4] Jairo canta a Ferrer CulturaBA está AÑO 6 disponible en [pág. 5] Veinte años no es poco [pág. 6] Música, maestros / Cómo arruinar su vida y/o www.buenosaires.gov.ar, Nº 346 clickeando en “Cultura”. Revista de distribución gratuita la de los demás - El humor de Santiago Varela [pág. 7] El humor de Rep / ¿Cómo llego? del Gobierno de la Ciudad Desde allí también de Buenos Aires [pág. 8] Además: agenda de actividades, del 26 de febrero al 4 de marzo de 2009. puede imprimirse. LA ÚLTIMA MILONGA AL AIRE LIBRE Orquesta Académica del Teatro Colón. Audiciones para cubrir vacan- Música sin límites. La Dirección General de Música del Ministerio de tes en sus filas para el curso de Práctica Orquestal 2009. Director Titu- Cultura de la Ciudad organiza las siguientes actividades. lar maestro Carlos calleja. Las pruebas se realizarán hasta mañana. Una CINE Y MÚSICA EN LAS VENAS. Estudio Urbano invita a disfrutar películas vez finalizada la inscripción, la Orquesta Académica del Teatro Colón donde el ingrediente musical es el principal protagonista y que tienen, además, enviará información del horario y lugar de cada prueba por correo elec- la virtud de ser cinematográficamente bellas. -

Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: the Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976

“Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 Valeria Manzano The Americas, Volume 70, Number 3, January 2014, pp. 393-427 (Article) Published by The Academy of American Franciscan History DOI: 10.1353/tam.2014.0030 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tam/summary/v070/70.3.manzano.html Access provided by Chicago Library (10 Feb 2014 08:01 GMT) T HE A MERICAS 70:3/January 2014/393–427 COPYRIGHT BY THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTORY “ROCK NACIONAL” AND REVOLUTIONARY POLITICS: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 n March 30, 1973, three weeks after Héctor Cámpora won the first presidential elections in which candidates on a Peronist ticket could Orun since 1955, rock producer Jorge Álvarez, himself a sympathizer of left-wing Peronism, carried out a peculiar celebration. Convinced that Cám- pora’s triumph had been propelled by young people’s zeal—as expressed in their increasing affiliation with the Juventud Peronista (Peronist Youth, or JP), an organization linked to the Montoneros—he convened a rock festival, at which the most prominent bands and singers of what journalists had begun to dub rock nacional went onstage. Among them were La Pesada del Rock- ’n’Roll, the duo Sui Géneris, and Luis Alberto Spinetta with Pescado Rabioso. In spite of the rain, 20,000 people attended the “Festival of Liberation,” mostly “muchachos from every working- and middle-class corner of Buenos Aires,” as one journalist depicted them, also noting that while the JP tried to raise chants from the audience, the “boys” acted as if they were “untouched by the political overtones of the festival.”1 Rather atypical, this event was nonetheless significant. -

Announcement of the Winners of the Fedora Prizes

Press release ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE June 2018 WINNERS OF THE FEDORA PRIZES June 7th, 2018 - Award Ceremony The Award Ceremony of the 4th edition of the FEDORA Prizes took place on June 7th, 2018 at the Bayerisches Staatsballett in Munich. FEDORA is a non-profit organization, which supports every year opera and ballet co-productions of excellence that involve emerging artists of different nationalities and backgrounds. Seven Stones, a new opera co-production led by the Aix-en-Provence Festival, won the FEDORA – GENERALI Prize for Opera 2018 (€150,000) and A Quiet Evening of Dance, a new ballet co-production of Sadler’s Wells in London won the FEDORA - VAN CLEEF & ARPELS Prize for Ballet 2018 (€100,000). For the first time, also two symbolic Prizes were awarded: ToThe True Story of King Kong, an interdisciplinary opera co-production lead by Theater Magdeburg, for obtaining the highest number of public votes on the new FEDORA Platform and to A Quiet Evening of Dance for managing the most successful crowdfunding campaign. Seven Stones A Quiet Evening of DancE Festival d’Aix-en-Provence Sadler’s Wells Composer: Ondřej Adámek Choreographer: William Forsythe Librettist: Sigurjón B Sigurðsson Dancers: Rauf Yasit, Brigel Gjoka, Jill Johnson, Christopher Stage Director & Choreographer: Eric Oberdorff Roman, Riley Watts, Parvaneh Scharafali, Ander Zabala © Rights reserved © Sadler’s Wells Seven Stones is a highly creative, non-traditional and A new production by ground-breaking choreographer William accessible opera from young Czech composer Ondřej Forsythe, A Quiet Evening of Dance features a range of Adámek and Icelandic poet Sjón (also lyricist for the singer choreography, from the sparse and analytic to baroque- Björk). -

Extracts of Orfeu Da Conceição (Translated by David Treece)

Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) The poems and songs here translated are from the play Orfeu da Conceição, by Vinicius de Moraes and Antonio Carlos Jobim. This selection was part of the libretto for “Playing with Orpheus”, performed by the King’s Brazil Ensemble in October 2016, as part of the Festival of Arts and Humanities at King’s College London. Orpheus Eurydice… Eurydice… Eurydice … The name that bids one to speak Of love: name of my love, which the wind Learned so as to pluck the flower’s petals Name of the nameless star… Eurydice… Coryphaeus The perils of this life are too many For those who feel passion, above all When a moon suddenly appears And hangs there in the sky, as if forgotten. And if the moonlight in its wild frenzy Is joined by some melody Then you must watch out For a woman must be there about. A woman must be there about, made Of music, moonlight and feeling And life won’t let her be, so perfect is she. A woman who is like the very Moon: So lovely that she leaves a trail of suffering So filled with innocence that she stands naked there. Orpheus Eurydice… Eurydice… Eurydice… The name that asks to speak Of love: name of my love, which the wind - 597 - RASILIANA: Journal for Brazilian Studies. ISSN 2245-4373. Vol. 9 No. 1 (2020). Extracts of Orfeu da Conceição (translated by David Treece) Learned so as to pluck the flower’s petals Name of the nameless star… Eurydice… A Woman’s name A woman’s name Just a name, no more… And a self-respecting man Breaks down and weeps And acts against his will And is deprived of peace. -

Nobel Week Stockholm 2018 – Detailed Information for the Media

Nobel Week Stockholm • 2018 Detailed information for the media December 5, 2018 Content The 2018 Nobel Laureates 3 The 2018 Nobel Week 6 Press Conferences 6 Nobel Lectures 8 Nobel Prize Concert 9 Nobel Day at the Nobel Museum 9 Nobel Week Dialogue – Water Matters 10 The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm 12 Presentation Speeches 12 Musical Interludes 13 This Year’s Floral Decorations, Concert Hall 13 The Nobel Banquet in Stockholm 14 Divertissement 16 This Year’s Floral Decorations, City Hall 20 Speeches of Thanks 20 End of the Evening 20 Nobel Diplomas and Medals 21 Previous Nobel Laureates 21 The Nobel Week Concludes 22 Follow the Nobel Prize 24 The Nobel Prize Digital Channels 24 Nobelprize org 24 Broadcasts on SVT 25 International Distribution of the Programmes 25 The Nobel Museum and the Nobel Center 25 Historical Background 27 Preliminary Timetable for the 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 30 Seating Plan on the Stage, 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 32 Preliminary Time Schedule for the 2018 Nobel Banquet 34 Seating Plan for the 2018 Nobel Banquet, City Hall 35 Contact Details 36 the nobel prize 2 press MeMo 2018 The 2018 Nobel Laureates The 2018 Laureates are 12 in number, including Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad, who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded 590 times to 935 Laureates Because some have been awarded the prize twice, a total of 904 individuals and 24 organisations have received a Nobel Prize or the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel -

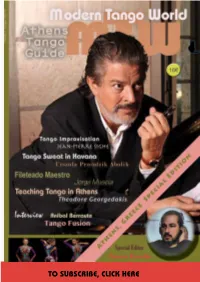

To Subscribe, Click Here — 2 —

— 1 — TO SUBSCRIBE, CLICK HERE — 2 — TO SUBSCRIBE, CLICK HERE Modern18 Tango World Athens Special Edition Editor Thanos Kasadis Table of Contents Greece Special Features Tango Acropilis Elena Gossi & Mestre Luis ............................................................ 03 An Argentine in Athens Fabian Ballejosi ......................................................... 06 Teaching Tango in Athens Theodore Georgedakis ....................................... 08 Guide to Tango in Greece ..................................................................................... 10 Maestro Fileteador Jorge Muscia ........................................................................... 18 Interview with Anibal Berraute (Tango Fusion) Marco Buso ..................... 22 Tango Sweat in Havana Urszula Przezdzik Abolik ............................................. 25 Tango Improvisation Jean-Pierre Sighe .............................................................................29 Un Tango Mas of German Kral Alexandru Eugen Cristea ............................. 32 The Tango Poetry & Literature of Rome Mario Abbatia ................................. 34 Our Advertisers ................................................................................................................. 37 New Tango Music Arndt Büssing ............................................................................... 38 Tango Moves: Parada (Sop) Raymond Lauzzana ................................................. 44 Letters to the Editor ...................................................................................................... -

Performeando Orfeu Negro

Performeando Orfeu Negro Leslie O’Toole The University of Arizona a película Orfeu Negro es una coproducción entre Brasil y Francia, con un direc- tor francés. Fue estrenada en 1959 con mucha aclamación crítica fuera de Brasil. Ganó una cantidad de premios, incluyendo el Palm d’Or en 1959 en Cannes, Llos premios Golden Globe y Academy Award para en 1960 Mejor Película Extranjera y el premio BAFTA en 1961. Antes del premio BAFTA fue considerada una película francesa, pero con este premio recibió la atribución de ser una coproducción. Aunque la película era muy popular en todo el mundo, los brasileños tenían algunas frustra- ciones con la imagen extranjera de Brasil que muestra. Orfeu Negro tiene un director, empresa de producción y equipo de rodaje francés, por eso los brasileños sentían que la película representaba la vida de las favelas de Rio de Janeiro en una luz demasiadamente romántica y estilizada. En 2001, Carlos Diegues produjo y dirigió una nueva versión, llamada Orfeu, que tiene lugar en las modernas favelas de Rio de Janeiro. Esta película, que muestra la banda sonora de Caetano Veloso, un famoso músico brasileño y uno de los fundadores del estilo tropicalismo, fue bien recibida por el publico brasileño pero no recibió mucha aclamación o atención fuera de Brasil. ¿Cómo podía embelesar una película como Orfeu Negro su audiencia mundial y por qué continúa de cautivar su atención? Creo que Orfeu Negro, con la metaforicalización de un mito, ha tocado tantas personas porque muestra nuestros deseos y humanidad. Propongo investigar cómo la película cumple esta visualización a través del uso de dife- rentes teóricos, filósofos y antropólogos, más predominantemente, Mikhail Bakhtin, Victor Turner y Joseph Roach. -

La Operita María De Buenos Aires

Sonia Alejandra López La operita María de Buenos Aires Texto: Horacio Ferrer - Música: Astor Piazzolla Informe preliminar1 La operita María de Buenos Aires es la primera obra conjunta de Horacio Ferrer y Astor Piazzolla, dos creadores importantísimos, uno de la literatura, el otro de la música de tango. ConMaría de Buenos Aires comienza una “sociedad de trabajo creativo” que en los siguientes años daría numerosas obras literario-musicales de relevante importancia. Una unión artística que, como diría Ferrer, “[...] ha sido una bella fatalidad” (Diana Piazzolla 1987: 193). De esta “bella fatalidad” nace María de Buenos Aires. La obra fue ya en el momento de su estreno y es retrospectivamente una expresión de la cultura musical y literaria porteña de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Piazzolla era consciente de ello y orgulloso comentaba: “[...] yo creo que ‘María de Buenos Aires’ es el documento más importante de lo que se ha hecho hasta ahora en el tango; nunca se hizo algo de este tipo [...]” (Speratti 1969: 126). Para sus autores significó esta obra una experiencia artística muy valiosa. Para ambos hay un “antes y un después” de la operita. De su experiencia durante la composición comenta Piazzolla: “Nació ahí [con María de Buenos Aires] un Piazzolla más cerebral, junto a un Piazzolla irremediablemente sentimental [...] Llegué al punto más alto adonde podía llegar en esa etapa de mi vida musical ...” (Diana Piazzolla 1987: 197). El presente escrito presenta fragmentariamente una primera colección de obser vaciones desarrolladas más detalladamente en un trabajo en preparación. 62 Sonia Alejandra López Por su parte cataloga Ferrer a la operita en 1996, casi veinte años después de la creación, como la obra “preferida” de entre todas las que realizó con el músico.2 La amistad Ferrer-Piazzolla comienza en 1954 (Ferrer 1977: 220). -

“MARÍA DE BUENOS AIRES” Di Astor Piazzolla, Nel Centenario Della Nascita

Giovedì 17 giugno, ore 11 Teatro Goldoni Presentazione della produzione lirica “MARÍA DE BUENOS AIRES” di Astor Piazzolla, nel centenario della nascita CONFERENZA STAMPA STAGIONE ESTIVA “USCIAMO A RIVEDER LE STELLE” Teatro Goldoni Livorno Venerdì 25, Sabato 26 e Domenica 27 giugno – ore 21.30 Stagione Lirica 2021 - Nel centenario della nascita di Astor Piazzolla MARÍA DE BUENOS AIRES Operita Tango musica Astor Piazzolla testi Horacio Ferrer - Sovratitoli a cura della Fondazione Teatro Goldoni Personaggi e interpreti María / Ombra di María Arianna Manganello El Duende/Lo Spirito Gianluca Ferrato Payador/Porteno/Ladron antiguo mayor/Analista primero/Vos de Ese Domingo Giacomo Medici Orchestra del Teatro Goldoni di Livorno direttore Igor Zobin regia Alessio Pizzech scene e costumi Flavia Ruggeri luci Michele Rombolini assistenti alla regia Stefania Paparella, Francesco Bonati, Noemi Piccorossi Stagisti della Verona Accademia per l’Opera Italiana Nuovo allestimento del Teatro Goldoni di Livorno in coproduzione con Associazione culturale Piccolo Opera Festival Biglietti: Intero € 15 – ridotto € 10 (under 25). I biglietti sono in vendita tutti i giorni dal martedì al sabato con orario 10-13 presso il botteghino del Teatro Goldoni (tel. 0586 204290) e nei giorni di spettacolo due ore prima dell’inizio della rappresentazione. Tutte le informazioni sulla produzione su www.goldoniteatro.it In occasione delle rappresentazioni di MARÍA DE BUENOS AIRES venerdì 25, sabato 26 e domenica 27 dalle ore 20 alle 21 al bar ristorante IL PALCOSCENICO AperiTango Musica, tango e aperitivo per tutti i possessori del biglietto dell’opera al prezzo speciale di € 4 Con l’intervento di Scuola di tango: Tango Barbaro Prima coppia di tangueros Gabriele Sassetti e Barbara Taccini Tutti i possessori di biglietto per una delle rappresentazioni dell’opera in programma al Teatro Goldoni il 25, 26 e 27 giugno, potranno avere uno speciale aperitivo presso il Bar-ristorante “Il Palcoscenico” al costo di € 4 dalle ore 20 alle ore 21 nei giorni di rappresentazione. -

Las Mil Y Una Vidas De Las Canciones

Las mil y una vidas de las canciones Abel Gilbert y Martín Liut (compiladores) Gilbert, Abel / Liut, Martín Las mil y una vidas de las canciones / Abel Gilbert ; Martín Liut. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Gourmet Musical Ediciones, 2019. 264 p. ; 23 x 15 cm. ISBN 978-987-3823-33-6 1. Música. 2. Historia Argentina. I. Liut, Martín II. Título CDD 780.982 Edición: Leandro Donozo Asistente editorial: Marcela Abad Corrección: Oscar Finkelstein Diseño de portada: Santi Pozzi Diseño de interiores y armado: Tomás Caramella © Martín Liut / Abel Gilbert, 2019 © Gourmet Musical Ediciones, 2019 Reservados todos los derechos de esta edición 1ra edición: marzo de 2019 ISBN 978-987-3823-33-6 Este libro fue posible en parte gracias al apoyo del Instituto Nacional de la Música. Esta edición de 2000 ejemplares se terminó de imprimir en Al Sur Producciones Gráficas srl (Wenceslao Villafañe 468, Bs. As.) en marzo de 2019. Hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723. Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra sin permiso escrito del editor. Gourmet Musical Ediciones Buenos Aires, Argentina [email protected] facebook.com/gourmetmusicalediciones - www.gourmetmusicalediciones.com Índices temáticos Índice de nombres 2 Minutos 197 Amar Azul 207, 212, 213 Anacrusa 42 A André y su Conjunto 71 ABBA 210 Apanovitch, Irene 180, 183 Abuelo, Miguel 169 Apicella, Mauro 100, 101, 103 Academia Bach de Stuttgart 177 Aprile, Andrew 160, 183 Academia de Educación 49 Arabarco, Osvaldo 151 Academia Italia 35 Arbolito 214 Accattoli, Cristian -

1718Studyguidemaria.Pdf

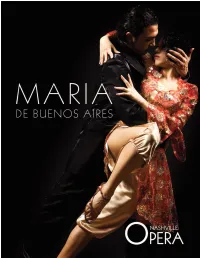

MARIA DE BUENOS AIRES A little tango opera in two parts for orchestra, narrator, and singers Texts by Horacio Ferrer | Music by Ástor Piazzolla Premiere May 8, 1968, Sala Planeta, Buenos Aires NOVEMBER 10, 11, 12, 2O17 The Noah Liff Opera Center Judy & Joe Barker | Jessica & Zach Liff Co-sponsors Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST Maria Cassandra Velesco* El Payador Luis Alejandro Orozco* El Duende Luis Ledesma* Tango Axis Mariela Barufaldi* Jeremías Massera* The Girl Zazou France Gray* Sofia Viglianco* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE JUDY & NOAH SUE & EARL LIFF FOUNDATION SWENSSON THE STORY Ástor Piazzolla’s tango opera, Maria de Buenos Aires, premiered on May 8, 1968, in Sala Planeta, Buenos Aires. The seductive quality of nuevo tango and the bandoneon play such an important role, they embody a central character in the story. Some say that the opera is a metaphor for tango and the city of Buenos Aires, with Maria herself being the personification of the tango. The surrealist plot is conveyed with the words of a narrator character and poet, El Payador, and his antithesis El Duende, an Argentinian goblin-spirit from South American mythology whose powers cause the loss of innocence. The opera, separated into two parts, first tells the story of the young Maria, her struggles on earth, and ultimate demise. The libretto states she “was born on the day God was drunk.” In the second part of the opera, we explore her existence as “Shadow Maria,” experiencing the dark underworld of Buenos Aires.