Airpower Through WWI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Service Newsletters 1918

PROPERTY OF 0.S.'100 ,.,'. ."~''';~ , t"',1.. :1.,•... ,"..A; A/' l .' Of'I:.J~EOF AIR FORCE HISTOR} r-:; .rfiL -:y.t / 1'rOll1 tho if£' .~ lfli"''';;.ewareDeJ;>artment nut:>.orizes the following: Irrespecti ve o f status in the draft, t>e ~Ur Service has been re- opened ro ..' i::lduc tion 0 f :,leC;:18.ni08and. of cand.idat es fo r comcu.ss i.one as " pi lots, bomber-a, observer s an d b8.11ool1ists, z,fter havi ng been. closed EW..oSptfor,a few isolated cLas se s for tile ;?c\st s1::: month s , The fast moving overseas of 2.11' s quad ...~ons, ~?lanes, motors and mate:;'1ial for Junerio8.n airclr<:nnes, fields, and asscl.lb1y :;;>151ts in :i<'rai'lce and E'l1g1and, together with the cOlW,?letion here of 29 flyu-€: :fields, 1200 de Ha'iilar.d 1::>lanes,6000 Mbe:dy motors, 't.l0 parts for ti"le first heavy l1igl:.t bombers, 6pOO trainii'lG planes and 12,500 tro.ini:1C e11c;i11oS,ha s led to the necessity of increasi:'Jg bOt}l tlle coranuas Loned 8:...10. tJJ8 enlis ted ~:~ersonne'l, in 0 rder to m~1nte.in full streng'th in ells count ry and continue t~le nec es sary flow . overseas. As e. r esu l t tl::,e Air Se::,'vice, alone, is now lia Lf as large agD,in as . the whole-,~i1e:dc8.ll )-l":';),y was at ti:e out'bre8Jc of 'Vlar. Ci viJ.iaYts have no t been gi ven an o))orttlni t'~T to ql.lalif;y as :9ilots since last L:ar'cl1. -

Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Civilian Involvement in the 1990-91 Gulf War Through the Civil Reserve Air Fleet Charles Imbriani Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE CIVILIAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE 1990-91 GULF WAR THROUGH THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By CHARLES IMBRIANI A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2012 Charles Imbriani defended this dissertation on October 4, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Peter Garretson Professor Directing Dissertation Jonathan Grant University Representative Dennis Moore Committee Member Irene Zanini-Cordi Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to Fred (Freddie) Bissert 1935-2012. I first met Freddie over forty years ago when I stared working for Pan American World Airways in New York. It was twenty-two year later, still with Pan Am, when I took a position as ramp operations trainer; and Freddie was assigned to teach me the tools of the trade. In 1989 while in Berlin for training, Freddie and I witnessed the abandoning of the guard towers along the Berlin Wall by the East Germans. We didn’t realize it then, but we were witnessing the beginning of the end of the Cold War. -

JP 3-09.3, Close Air Support, As a Basis for Conducting CAS

Joint Publication 3-09.3 Close Air Support 08 July 2009 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides joint doctrine for planning and executing close air support. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations and provides the doctrinal basis for interagency coordination and for US military involvement in multinational operations. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs) and prescribes joint doctrine for operations, education, and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing their appropriate plans. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of the overall objective. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders of combatant commands, subunified commands, joint task forces, and subordinate components of these commands, and the Services. b. The guidance in this publication is authoritative; as such, this doctrine will be followed except when, in the judgment of the commander, exceptional circumstances dictate otherwise. If conflicts arise between the contents of this publication and the contents of Service publications, this publication will take precedence unless the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, normally in coordination with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has provided more current and specific guidance. -

DUTCH COUNTRY AUCTIONS the Stamp Center Presents PUBLIC AUCTION #334 Now in Our 42Nd Year

DUTCH COUNTRY AUCTIONS The Stamp Center Presents PUBLIC AUCTION #334 Now In Our 42nd Year #1051 #1418 #503 #986 Tuesday, May 18, 2021 – 10 am ET Wednesday, May 19, 2021 – 10 am ET Thursday, May 20, 2021 – 10 am ET 302-478-8740 www.dutchcountryauctions.com 4115 Concord Pike • Wilmington, DE 19803 48009 Dutch Country Auctions.pdf1 CONDITIONS OF SALE Bidding 1. The placing of a bid will constitute acceptance of the conditions of sale. 2. All bids are per lot as numbered in the catalog. The right is reserved to withdraw any lot or lots and to group two or more lots. 3. Lots are sold to the highest bidder at one advance over the second highest bid. The auctioneer shall regulate the bidding and in the event of any dispute the auctioneer’s decision shall be final. 4. The auctioneer shall not be liable for errors and omissions in executing instructions to bid. 5. Unlimited bids and bids believed not to be made in good faith will be respectfully declined. 6. Minimum bid on any lot is $50.00. 7. All lots will be sold at the price for which they are knocked down by the auctioneer, plus a commission of 15%. Payment of Purchases 8. Successful bidders will be notified of lots purchased and must remit before lots are delivered. Persons who are known to us may, at our option, have purchases forwarded for immediate payment. 9. Terms are immediate payment in U.S. funds on receipt of the invoice. Payment by credit card will be subject to a 2% service charge. -

The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons History Undergraduate Theses History Winter 3-12-2020 The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. Duncan Hamlin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Hamlin, Duncan, "The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations." (2020). History Undergraduate Theses. 44. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses/44 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. The American Army Air Service During World War I's Hundred Days Offensive: Looking at Reconnaissance, Bombing and Pursuit Aviation in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Operations. A Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Undergraduate History Program of the University of Washington By Duncan Hamlin University of Washington Tacoma 2020 Advisor: Dr. Nicoletta Acknowledgments I would first like to thank Dr. Burghart and Dr. Nicoletta for guiding me along with this project. This has been quite the process for me, as I have never had to write a paper this long and they both provided a plethora of sources, suggestions and answers when I needed them. -

"The Spirit Of" Due Process As Advocated by Charles Lindbergh

CLARK_57-1_POST CLARK PAGES (DO NOT DELETE) 3/25/2020 10:56 AM “The Spirit of” Due Process as Advocated by Charles Lindbergh: Revisiting Pacific Air Transport v. United States, 98 Ct. Cl. 649 (1942) THOMAS C. CLARK, II* * © 2020 Thomas C. Clark, II. Judge, 22nd Circuit Court, St. Louis, Missouri. This author acknowledges the several individuals who offered invaluable assistance and provided unconditional support with this endeavor. With gratitude, the author acknowledges the guidance of his master’s thesis committee members and skilled scholars, Chair Shawn Marsh, Ph.D., Richard Bjur, Ph.D., and Matthew Leone, Ph.D. The author appreciates his great friend, an academic intellect and a devoted cleric, Rev. Richard Quirk, Ph.D., for providing both the needed historical context and the prevailing political considerations of this time period; recognizes lawyer and friend Michael Silbey for sharing his unparalleled skill and thoughtful counsel when assisting with this undertaking; acknowledges great friends of prodigious legal talent, Catherine A. Schroeder, Yvonne Yarnell, John Wilbers, Jill Hunt, and Hon. Elizabeth Hogan for their encouragement, friendship, and uncompromising loyalty; thanks influential legal mentors Shirley Rodgers and the Hon. John Riley for shaping both legal and judicial careers; thanks the most thoughtful jurists presiding throughout the country—especially the talented judge from Arkansas—who attended classes at the University of Nevada-Reno with the author, and inspired his efforts to both pursue the judicial studies degree and draft this writing; appreciates his revered sister and illustrious brother-in-law, Catherine and D.J. Lutz, for their support and refreshing humor as well as thanks the loving and highly charismatic Carl and Jane Bolte. -

B-25 Mitchell

Airpower Classics Artwork by Zaur Eylanbekov B-25 Mitchell On April 18, 1942, Army Air Forces Lt. Col. James “Pappy” Gunn’s fabled 75 mm cannon. The Mitchell H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, leading a force of 16 B-25B was never the fastest, most maneuverable, or medium bombers and crews, took off from the best-looking medium bomber. However, it grew to aircraft carrier USS Hornet and bombed Tokyo be the most heavily armed and was more versatile and other targets. It was the first time US aircraft than any—even the German Junkers Ju 88. had struck at Japan, and the raid immortalized both Doolittle and the B-25 Mitchell. The North Noted for its excellent handling characteristics, the American Aviation bomber went on to become a B-25 performed remarkably well in many roles, workhorse in every theater of World War II. including medium- and low-altitude bomber, close air support, photo reconnaissance, anti- North American proposed the new Model NA-62, submarine warfare, patrol, and—when occasion derived from a series of earlier prototypes, in a demanded—tactical fighter. Later it was used as 1939 competition. The Army bought it right off a pilot and navigator trainer, and became much the drawing board, ordering 184 of the airplanes. beloved in that role. In peacetime, it served as an The clean, lean lines of the B-25 delivered good executive transport, firefighter, camera airplane, performance and facilitated both mass produc- test vehicle, and crop duster. The last B-25 train- tion and maintenance. Built in 10 major models, ers remained in service at Reese AFB, Tex., until with numerous variants, the B-25 was particularly finally retiring in January 1959—nearly 17 years adaptable to field modifications. -

The Aeronautical Division, US Signal Corps By

The First Air Force: The Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps By: Hannah Chan, FAA history intern The United States first used aviation warfare during the Civil War with the Union Army Balloon Corps (see Civil War Ballooning: The First U.S. War Fought on Land, at Sea, and in the Air). The lighter-than-air balloons helped to gather intelligence and accurately aim artillery. The Army dissolved the Balloon Corps in 1863, but it established a balloon section within the U.S. Signal Corps, the Army’s communication branch, during the Spanish-American War in 1892. This section contained only one balloon, but it successfully made several flights and even went to Cuba. However, the Army dissolved the section after the war in 1898, allowing the possibility of military aeronautics advancement to fade into the background. The Wright brothers' successful 1903 flight at Kitty Hawk was a catalyst for aviation innovation. Aviation pioneers, such as the Wright Brothers and Glenn Curtiss, began to build heavier-than-air aircraft. Aviation accomplishments with the dirigible and planes, as well as communication innovations, caused U.S. Army Brigadier General James Allen, Chief Signal Officer of the Army, to create an Aeronautical Division on August 1, 1907. The A Signal Corps Balloon at the Aeronautics Division division was to “have charge of all matters Balloon Shed at Fort Myer, VA Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum pertaining to military ballooning, air machines, and all kindred subjects.” At its creation, the division consisted of three people: Captain (Capt.) Charles deForest Chandler, head of the division, Corporal (Cpl.) Edward Ward, and First-class Private (Pfc.) Joseph E. -

Vantage Points Perspectives on Airpower and the Profession of Arms

00-Frontmatter 3x5 book.indd 4 8/9/07 2:39:03 PM Vantage Points Perspectives on Airpower and the Profession of Arms Compiled by CHARLES M. WESTENHOFF Colonel, USAF, Retired MICHAEL D. DAVIS, PHD Colonel, USAF DANIEL MORTENSEN, PHD JOHN L. CONWAY III Colonel, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2007 00-Frontmatter 3x5 book.indd 1 8/9/07 2:39:02 PM Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Cataloging Data Vantage points : perspectives on airpower and the profes- sion of arms / compiled by Charles M. Westenhoff . [et al.] p. ; cm. ISBN 978-1-58566-165-7 1. Air power—Quotations, maxims, etc. 2. Air warfare— Quotations, maxims, etc. 3. Military art and science— Quotations, maxims, etc. I. Westenhoff, Charles M. 355.4—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or im- plied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. All photographs are courtesy of the US government. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-5962 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii 00-Frontmatter 3x5 book.indd 2 8/9/07 2:39:03 PM Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v THEORY OF WAR . 1 Patriotism . 8 AIR, Space, AND CYBER POWER . 10 DOCTRINE . 21 Education, TRAINING, AND LESSONS LEARNED . 24 Preparedness, SECURITY, AND FORCE PROTECTION . 27 PLANNING . 30 LEADERSHIP AND PROFESSIONALISM . 32 CHARACTER AND LEADERSHIP TRAITS . 35 TECHNOLOGY . -

Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War

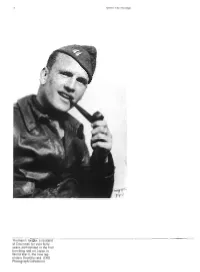

Queen City Heritage Thomas C. Griffin, a resident of Cincinnati for over forty years, participated in the first bombing raid on Japan in World War II, the now leg- endary Doolittle raid. (CHS Photograph Collection) Winter 1992 Navigating from Shangri-La Navigating from Shangri- La: Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War Kevin C. McHugh served as Cincinnati's oral historian for "one of America's biggest gambles"5 of World War II, the now legendary Doolittle Raid on Japan. A soft-spoken man, Mr. Griffin Over a half century ago on April 18, 1942, characteristically downplays his part in the first bombing the Cincinnati Enquirer reported: "Washington, April 18 raid on Japan: "[It] just caught the fancy of the American — (AP) — The War and Navy Departments had no confir- people. A lot of people had a lot worse assignments."6 mation immediately on the Japanese announcement of the Nevertheless, he has shared his wartime experiences with bombing of Tokyo."1 Questions had been raised when Cincinnati and the country, both in speaking engagements Tokyo radio, monitored by UPI in San Francisco, had sud- and in print. In 1962 to celebrate the twentieth anniversary denly gone off the air and then had interrupted program- of the historic mission, the Cincinnati Enquirer highlight- ming for a news "flash": ed Mr. Griffin's recollections in an article that began, Enemy bombers appeared over Tokyo for the "Bomber Strike from Carrier Recalled."7 For the fiftieth first time since the outbreak of the current war of Greater anniversary in 1992, the Cincinnati Post shared his adven- East Asia. -

HELP from ABOVE Air Force Close Air

HELP FROM ABOVE Air Force Close Air Support of the Army 1946–1973 John Schlight AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM Washington, D. C. 2003 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schlight, John. Help from above : Air Force close air support of the Army 1946-1973 / John Schlight. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Close air support--History--20th century. 2. United States. Air Force--History--20th century. 3. United States. Army--Aviation--History--20th century. I. Title. UG703.S35 2003 358.4'142--dc22 2003020365 ii Foreword The issue of close air support by the United States Air Force in sup- port of, primarily, the United States Army has been fractious for years. Air commanders have clashed continually with ground leaders over the proper use of aircraft in the support of ground operations. This is perhaps not surprising given the very different outlooks of the two services on what constitutes prop- er air support. Often this has turned into a competition between the two serv- ices for resources to execute and control close air support operations. Although such differences extend well back to the initial use of the airplane as a military weapon, in this book the author looks at the period 1946- 1973, a period in which technological advances in the form of jet aircraft, weapons, communications, and other electronic equipment played significant roles. Doctrine, too, evolved and this very important subject is discussed in detail. Close air support remains a critical mission today and the lessons of yesterday should not be ignored. This book makes a notable contribution in seeing that it is not ignored. -

10, George C. Marshall

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #10 “George C. Marshall: Global Commander” Forrest C. Pogue, 1968 It is a privilege to be invited to give the tenth lecture in a series which has become widely-known among teachers and students of military history. I am, of course, delighted to talk with you about Gen. George C. Marshall with whose career I have spent most of my waking hours since1956. Douglas Freeman, biographer of two great Americans, liked to say that he had spent twenty years in the company of Gen. Lee. After devoting nearly twelve years to collecting the papers of General Marshall and to interviewing him and more than 300 of his contemporaries, I can fully appreciate his point. In fact, my wife complains that nearly any subject from food to favorite books reminds me of a story about General Marshall. If someone serves seafood, I am likely to recall that General Marshall was allergic to shrimp. When I saw here in the audience Jim Cate, professor at the University of Chicago and one of the authors of the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, I recalled his fondness for the works of G.A. Henty and at once there came back to me that Marshall once said that his main knowledge of Hannibal came from Henty's The Young Carthaginian. If someone asks about the General and Winston Churchill, I am likely to say, "Did you know that they first met in London in 1919 when Marshall served as Churchill's aide one afternoon when the latter reviewed an American regiment in Hyde Park?" Thus, when I mentioned to a friend that I was coming to the Air Force Academy to speak about Marshall, he asked if there was much to say about the General's connection with the Air Force.