NECROMANCY</ET>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Magic & White Supremacy

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-23-2021 Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power Nicholas Charles Peters Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Peters, Nicholas Charles, "Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 962. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power By Nicholas Charles Peters An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in English and University Honors Thesis Adviser Dr. Michael Clark Portland State University 2021 1 “Being burned at the stake was an empowering experience. There are secrets in the flames, and I came back with more than a few” (Head 19’15”). Burning at the stake is one of the first things that comes to mind when thinking of witchcraft. Fire often symbolizes destruction or cleansing, expelling evil or unnatural things from creation. “Fire purges and purifies... scatters our enemies to the wind. -

Constructing the Witch in Contemporary American Popular Culture

"SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES": CONSTRUCTING THE WITCH IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Catherine Armetta Shufelt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor Dr. Andrew M. Schocket Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Esther Clinton © 2007 Catherine A. Shufelt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor What is a Witch? Traditional mainstream media images of Witches tell us they are evil “devil worshipping baby killers,” green-skinned hags who fly on brooms, or flaky tree huggers who dance naked in the woods. A variety of mainstream media has worked to support these notions as well as develop new ones. Contemporary American popular culture shows us images of Witches on television shows and in films vanquishing demons, traveling back and forth in time and from one reality to another, speaking with dead relatives, and attending private schools, among other things. None of these mainstream images acknowledge the very real beliefs and traditions of modern Witches and Pagans, or speak to the depth and variety of social, cultural, political, and environmental work being undertaken by Pagan and Wiccan groups and individuals around the world. Utilizing social construction theory, this study examines the “historical process” of the construction of stereotypes surrounding Witches in mainstream American society as well as how groups and individuals who call themselves Pagan and/or Wiccan have utilized the only media technology available to them, the internet, to resist and re- construct these images in order to present more positive images of themselves as well as build community between and among Pagans and nonPagans. -

Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K

Volume 39 Number 2 Article 2 4-23-2021 Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle Oleksandra Filonenko Petro Mohyla Black Sea National University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Recommended Citation Filonenko, Oleksandra (2021) "Magic, Witchcraft, and Faërie: Evolution of Magical Ideas in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea Cycle," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 39 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract In my article, I discuss a peculiar connection between the persisting ideas about magic in the Western world and Ursula Le Guin's magical world in the Earthsea universe and its evolution over the decades. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

Divination, According to the Routledge Encyclopaedia

INTRODUCTION1 n Divination, according to the Routledge Encyclopaedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology, comprises ‘culturally sanctioned methods of arriving at a judge- ment of the unknown through a consideration of incomplete evidence’ (Willis 2012: 201). In Chinese, it is often referred to as ‘calculating fate’ (suanming 算命). In this ethnography, divination mainly refers to the multiple forms of Chinese divination using traditional techniques without involving communication with gods and other beings. Its text-based knowledge with a coherent system of symbols and a naturalist ontology are a result of centuries of development. Two reactions were common during my fieldwork on divination. Often, people would laugh when they heard the topic of my research; several people would gather around, and the whole circle would burst into laughter. However, when it was a private chat with two or three people, their response was, ‘Ha-ha! You study fate calculation?!’ But they usually showed great interest after their initial chuckle and would ask me, ‘Do you think it is accurate?’ Another commonplace event was that whenever I met a diviner for the first time, he or she always talked eloquently for hours to convey the positive meaning of their vocation, such as the grand role divination has played in Chinese culture, and the accuracy of their predictions. Anthropologists studying Chinese popular religion often have to deal with ‘people’s insouciant attitude toward explicit interpretation’ (Weller 1994: 7); my informants, on the contrary, had a strong motivation to offer me the meaning of their practice and did it eloquently with an ‘interpretative noise’ through their constant bragging and legitimation efforts. -

Family Oi 15 Is Homeless? Fill' Settle %R Four Rooms Town Bows to Demand/ on Sewers

Coverage S4WNSHIR Complete News> Pictures A Newspapesv Devoted Presented Fairly, Clearly To the Community Interest And Impartially Each VOL. XIII—NO, 33 FORDS, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY 26, 1951 PRICE FIVE CENTS New Bolls Arrive Family oi 15 Is Homeless?Town Bows fill' Settle %r Four Rooms To Demand/ "—This tune-The .Inde- in Perth Amboy. pendent-Leader' lias Undertaken "We do not want to separate a , difficult task—but perhaps our family," Mrs." Jordan said, On Sewers some pJace in this, Township "because no good will come of it. A family should stay together if By CHARLES E. GREGORY May be Reintroduced there is someone who can help 4PS Snd a home for a family of 15. the members are to be happy. $2,500,000 Installation Later Including Quota " * S 2 : Maybe somebody can provide us Seen Unavoidable; May Just as soon as I wash out Of Licenses Permitted Yesterday, the family of Mr. with a home, even if it is only a few things today, I am go and Mrs. Alfred' Jordan, Frame four rooms. Even though we are Include Incinerator > ing to light out to see what I RARITAN TOWNSHIP — The, 1 Street, wa| dispossessed. The a big family, we take care of limited distribution liquor; li- JondSord has been trying- to gret things and are not destructive." WOODBRIDGE—Immediate ac- • can find out about building csnss ordinance which was due for the apartment for his own use :!: S :;: tion will be taken by the Town schools. pablic hearing last night was with- for over a year," and finally the Both local and county welfare Committee to create a Sewer Au- * * * di awn by Commissioner Julius courts decided that he had been boards have attempted to find thority as a result of a directive Engel, who introduced it originally, patient, indeed. -

The Cultural Evolution of Epistemic Practices: the Case of Divination Author: Ze Hong A1, Joseph Henricha

Title: The cultural evolution of epistemic practices: the case of divination Author: Ze Hong a1, Joseph Henricha Author Affiliations: a Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, 02138, Cambridge, MA, United States Keywords: cultural Evolution; divination; information transmission; Bayesian reasoning 1 To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT While a substantial literature in anthropology and comparative religion explores divination across diverse societies and back into history, little research has integrated the older ethnographic and historical work with recent insights on human learning, cultural transmission and cognitive science. Here we present evidence showing that divination practices are often best viewed as an epistemic technology, and formally model the scenarios under which individuals may over-estimate the efficacy of divination that contribute to its cultural omnipresence and historical persistence. We found that strong prior belief, under-reporting of negative evidence, and mis-inferring belief from behavior can all contribute to biased and inaccurate beliefs about the effectiveness of epistemic technologies. We finally suggest how scientific epistemology, as it emerged in the Western societies over the last few centuries, has influenced the importance and cultural centrality of divination practices. 2 1. INTRODUCTION The ethnographic and historical record suggests that most, and potentially all, human societies have developed techniques, processes or technologies that reveal otherwise hidden or obscure information, often about unknown causes or future events. In historical and contemporary small-scale societies around the globe, divination—"the foretelling of future events or discovery of what is hidden or obscure by supernatural or magical means” –has been extremely common, possibly even universal (Flad 2008; Boyer 2020). -

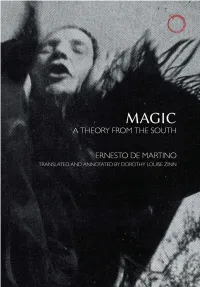

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

The Evolution of Variability in Magic, Divination and Religion

THE EVOLUTION OF VARIABILITY IN MAGIC, DIVINATION AND RELIGION: A MULTI-LEVEL SELECTION ANALYSIS A Dissertation by CATHARINA LAPORTE Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Michael S. Alvard Committee Members, Jeffrey Winking D. Bruce Dickson Jane Sell Head of Department, Cynthia A. Werner December 2013 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2013 Catharina Laporte ABSTRACT Religious behavior varies greatly both with-in cultures and cross-culturally. Throughout history, scientific scholars of religion have debated the definition, function, or lack of function for religious behavior. The question remains: why doesn’t one set of beliefs suit everybody and every culture? Using mixed methods, the theoretical logic of Multi-Level Selection hypothesis (MLS) which has foundations in neo-evolutionary theory, and data collected during nearly two years of field work in Macaé Brazil, this study asserts that religious variability exists because of the historic and dynamic relationship between the individual, the family, the (religious) group and other groups. By re-representing a nuanced version of Elman Service’s sociopolitical typologies together with theorized categories of religion proposed by J.G. Frazer, Anthony C. Wallace and Max Weber, in a multi-level nested hierarchy, I argue that variability in religious behavior sustains because it provides adaptive advantages and solutions to group living on multiple levels. These adaptive strategies may be more important or less important depending on the time, place, individual or group. MLS potentially serves to unify the various functional theories of religion and can be used to analyze why some religions, at different points in history, may attract and retain more adherents by reacting to the environment and providing a dynamic balance between what the individual needs and what the group needs. -

Magic & Witchcraft in Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kohnert, Dirk Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa World Development Suggested Citation: Kohnert, Dirk (1996) : Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa, World Development, ISSN 0305-750X, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 24, Iss. 8, pp. 1347-1355, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00045-9 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118614 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Authors version – published in: World Development, vol. 24, No. 8, 1996, pp. 1347-1355 Magic and Witchcraft Implications for Democratization and Poverty-Alleviating Aid in Africa Dirk Kohnert 1) Abstract The belief in occult forces is still deeply rooted in many African societies, regardless of education, religion, and social class of the people concerned. -

And Corpse-Divination in the Paris Magical Papyri (Pgm Iv 1928-2144)

necromancy goes underground 255 NECROMANCY GOES UNDERGROUND: THE DISGUISE OF SKULL- AND CORPSE-DIVINATION IN THE PARIS MAGICAL PAPYRI (PGM IV 1928-2144) Christopher A. Faraone The practice of consulting the dead for divinatory purposes is widely practiced cross-culturally and firmly attested in the Greek world.1 Poets, for example, speak of the underworld journeys of heroes, like Odys- seus and Aeneas, to learn crucial information about the past, present or future, and elsewhere we hear about rituals of psychagogia designed to lead souls or ghosts up from the underworld for similar purposes. These are usually performed at the tomb of the dead person, as in the famous scene in Aeschylus’ Persians, or at other places where the Greeks believed there was an entrance to the underworld. Herodotus tells us, for instance, that the Corinthian tyrant Periander visited an “oracle of the dead” (nekromanteion) in Ephyra to consult his dead wife (5.92) and that Croesus, when he performed his famous comparative testing of Greek oracles, sent questions to the tombs of Amphiaraus at Oropus and Trophonius at Lebedeia (1.46.2-3). Since Herodotus is heavily dependent on Delphic informants for most of Croesus’ story, modern readers are apt to forget that there were, in fact, two oracles that correctly answered the Lydian king’s riddle: the oracle of Apollo at Delphi and that of the dead hero Amphiaraus. The popularity of such oracular hero-shrines increased steadily in Hel- lenistic and Roman times, although divination by dreams gradually seems to take center stage.2 It is clear, however, that the more personal and private forms of necromancy—especially consultations at the grave—fell into disfavor, especially with the Romans, whose poets repeatedly depict horrible 1 For a general overview of the Greek practices and discussions of the specific sites mentioned in this paragraph, see A. -

Continuing Conjure: African-Based Spiritual Traditions in Colson Whitehead’S the Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’S Sing, Unburied, Sing

religions Article Continuing Conjure: African-Based Spiritual Traditions in Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing James Mellis Guttman Community College, 50 West 40th St., New York, NY 10018, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 April 2019; Accepted: 23 June 2019; Published: 26 June 2019 Abstract: In 2016 and 2017, Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing both won the National Book Award for fiction, the first time that two African-American writers have won the award in consecutive years. This article argues that both novels invoke African-based spirituality in order to create literary sites of resistance both within the narrative of the respective novels, but also within American culture at large. By drawing on a tradition of authors using African-based spiritual practices, particularly Voodoo, hoodoo, conjure and rootwork, Whitehead and Ward enter and engage in a tradition of African American protest literature based on African spiritual traditions, and use these traditions variously, both as a tie to an originary African identity, but also as protection and a locus of resistance to an oppressive society. That the characters within the novels engage in African spiritual traditions as a means of locating a sense of “home” within an oppressive white world, despite the novels being set centuries apart, shows that these traditions provide a possibility for empowerment and protest and can act as a means for contemporary readers to address their own political and social concerns. Keywords: voodoo; conjure; African-American literature; protest literature; African American culture; Whitehead; Ward; American literature; popular culture And we are walking together, cause we love one another There are ghosts at our table, they are feasting tonight.