Black Magic & White Supremacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Inimitable Sarah Paulson Is the Future Of

he won an Emmy, SAG Award and Golden Globe for her bravura performance as Marcia Clark in last year’s FX miniseries, The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story, but it took Sarah Paulson almost another year to confirm what the TV industry really thinks about her acting chops. Earlier this year, her longtime collaborator and O.J. executive producer Ryan Murphy offered the actress the lead in Ratched, an origin story he is executive producing that focuses on Nurse Ratched, the Siconic, sadistic nurse from the 1975 film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Murphy shopped the project around to networks, offering a package for the first time that included his frequent muse Paulson attached as star and producer. “That was very exciting and also very scary, because I thought, oh God, what if they take this out, and people are like, ‘No thanks, we’re good. We don’t need a Sarah Paulson show,’” says Paulson. “Thankfully, it all worked out very well.” In the wake of last year’s most acclaimed TV performance, everyone—TV networks and movie studios alike—wants to be in business with Paulson. Ratched sparked a high-stakes bidding war, with Netflix ultimately fending off suitors like Hulu and Apple (which is developing an original TV series strategy) for the project last month, giving the drama a hefty Why the inimitable two-season commitment. And that is only one of three high- profile TV series that Paulson will film over the next year. In Sarah Paulson is the 2018, she’ll begin production on Katrina, the third installment in Murphy’s American Crime Story anthology series for FX, and continue on the other Murphy FX anthology hit that future of TV. -

The Perpetuation of Historical Myths in New Orleans Tourism

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-31-2021 Don’t Be Myth-taken: The Perpetuation of Historical Myths in New Orleans Tourism Madeleine R. Roach University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Roach, Madeleine R., "Don’t Be Myth-taken: The Perpetuation of Historical Myths in New Orleans Tourism" (2021). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2902. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2902 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Don’t Be Myth-taken: The Perpetuation of Historical Myths in New Orleans Tourism A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the in the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History By Madeleine Roach B.A. -

AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 9 Pasfox

AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 - 9 | Pasfox AMERICAN HORROR STORY TEMP 9 CAP 8 - 9 | Pasfox 1 / 3 2 / 3 Jun 29, 2020 — American Horror Story - 1984 (Temporada 9) capitulo 8 parte 19. 704 views704 views. Premiered Jun 29, 2020. Critics Consensus: A near-perfect blend of slasher tropes and American Horror Story's trademark twists, 1984 is a bloody good time. 2019, FX, 9 episodes, ... Oct 31, 2019 — Cast members from seasons past return to haunt the current AHS season. ... 10/01/19American Horror Story: 1984 | Season 9 Ep. 3: Slashdance .... Nov 14, 2019 — 'American Horror Story: 1984' will feature a killer soundtrack with a bunch of '80s classics during the season. ... Episode 9: Final Girl.. Oct 22, 2013 — Banda sonora de la serie American Horror Story: Coven*Intento actualizarla ... 8. House of the Rising Sun. Lauren O'Connell. 3:05. 9. Pie IX.. 29, 2021 American Horror Stories. iCarly 1×09. HD. Episodio 9. T1 E9 / Jul. ... Rápidos y Furiosos 9 (2021). 2021. Cielo rojo sangre (2021). 0. Destacado ... Sep 18, 2019 — American Horror Story Temporada 9 Trailer Oficial Subtitulado ... American Horror Story 6: Roanoke capítulo 8 y 9 | Review con spoilers.. La familia ingalls -Temporada 9 Cap 17 (5-5). 00:08:28 11.63 MB Series ... Battlestar Galactica de los 80 Episodio 2 cap 8 . 00:04:58 6.82 MB .... ... Freddy Krueger Jason Bracelet American Horror Story Classic Horror Movies ... Baggy Soft Slouchy Beanie Hat Stretch Infinity Scarf Head Wrap Cap, 8 Pack .... Dónde ver American Horror Story - Temporada 2? ¡Prueba a ver si Netflix, iTunes, Amazon o cualquier otro servicio te deja reproducirlo en streaming, .. -

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

The Mythology of Marie Laveau in and out of the Archive (2019) Directed by Dr

CARTER, MORGAN E., M.A. Looking For Laveau: The Mythology of Marie Laveau In and Out of the Archive (2019) Directed by Dr. Tara T. Green. 97 pp. The purpose of this work is to engage with the proliferation of the myth of Marie Laveau, the nineteenth-century Voodoo figure of New Orleans, Louisiana and its multiple potentialities as both a tool of investment in whiteness as a form of intellectual property as well as a subject for myth as uplift, refusal, and resistance in terms of southern black womanhood and the critically imaginary. In this work, I create a trajectory of work that has endeavored to “recover” Laveau within institutionalized forms of knowing, specifically taking to task projects of recovery that attempt to present Laveau as a figure of strong leadership for women through institutionalized spaces and forms of knowledge, such as the archive while simultaneously dismissing other, “nonacademic” proliferations of the Laveau myth. This thesis serves to decenter the research, reading, and writing of the Laveau mythology as within the academy, which ostensibly serves white and normative generated and centered ways of knowing, identifying, and articulating, in favor of a methodology that accounts for cultural forms of mythologies that center memory, lineage, and communal identification. Through this critical work, I hope to supply a critical imaginary of what a Creole/Cajun southern feminism would look like, and how it is deeply intertwined with gendered and racialized nuances that are specific to region and community. LOOKING FOR LAVEAU: THE MYTHOLOGY OF MARIE LAVEAU IN AND OUT OF THE ARCHIVE by Morgan E. -

A Critical Analysis of American Horror Story: Coven

Volume 5 ׀ Render: The Carleton Graduate Journal of Art and Culture Witches, Bitches, and White Feminism: A Critical Analysis of American Horror Story: Coven By Meg Lonergan, PhD Student, Law and Legal Studies, Carleton University American Horror Story: Coven (2013) is the third season an attempt to tell a better story—one that pushes us to imag- analysis thus varies from standard content analysis as it allows of the popular horror anthology on FX1. Set in post-Hurricane ine a better future. for a deeper engagement and understanding of the text, the Katrina New Orleans, Louisiana, the plot centers on Miss Ro- symbols and meaning within the text, and theoretical relation- This paper combines ethnographic content analysis bichaux’s Academy and its new class of female students— ships with other texts and socio-political realities. This method and intersectional feminist analysis to engage with the televi- witches descended from the survivors of the witch trials in Sa- is particularly useful for allowing the researcher deep involve- sion show American Horror Story: Coven (2013) to conduct a lem, Massachusetts in 16922. The all-girls school is supposed ment with the text to develop a descriptive account of the com- close textual reading of the show and unpack how the repre- to be a haven for witches to learn about their heritage and plexities of the narrative (Ferrell et al. 2008, 189). In closely sentations of a diversity of witches can be read and under- powers while fostering a community which protects them from examining the text (Coven) to explore the themes and relation- stood as representing a diversity of types of feminism. -

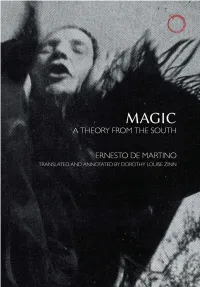

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

DAVID KLOTZ Music Editor TELEVISION CREDITS

DAVID KLOTZ Music Editor David Klotz has devoted his career to the music side of the film and tv industry, primarily as a music editor, but also as a composer, songwriter and music supervisor. He has won six Emmy awards for his work on Stranger Things, Game of Thrones, and American Horror Story. He got his start music supervising Christopher Nolan’s critically acclaimed film, Memento. Soon after, he moved into music editing, working on the shows Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly, and Blade, the TV Series, to name a few. In 2005, he formed Galaxy Beat Media, his music editorial and production company, working on TV shows including Entourage, Prison Break, Glee, and the Marvel feature film, Iron Man. David co-wrote and performed the theme song to the 2001 Robert Rodriguez blockbuster, Spy Kids. He most recently produced and arranged a cover of the 1984 classic “Never Ending Story” for Stranger Things Season 3, available on the show’s soundtrack album. David’s band Dream System 8 has created music for dozens of TV shows including 9-1-1, American Horror Story, Scream Queens, and Pose. TELEVISION CREDITS Perry Mason (TV Series) I Am Not Okay with This (TV Series) Executive Producers: Robert Downey Jr., Susan Downey, Executive Producers: Josh S. Barry, Dan Cohen, Jonathan Ron Fitzgerald, Rolin Jones, Timothy Van Patten, Entwistle, Christy Hall, Dan Levine & Shawn Levy Matthew Rhys, Amanda Burrell & Joseph Horacek 21 Laps Entertainment/Netflix HBO American Horror Story (TV Series – Seasons 1- Ratched (TV Series) 10) Executive Producers: -

Magic & Witchcraft in Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kohnert, Dirk Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa World Development Suggested Citation: Kohnert, Dirk (1996) : Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa, World Development, ISSN 0305-750X, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 24, Iss. 8, pp. 1347-1355, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00045-9 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118614 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Authors version – published in: World Development, vol. 24, No. 8, 1996, pp. 1347-1355 Magic and Witchcraft Implications for Democratization and Poverty-Alleviating Aid in Africa Dirk Kohnert 1) Abstract The belief in occult forces is still deeply rooted in many African societies, regardless of education, religion, and social class of the people concerned. -

The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE

Christendom v. Clericus: The Punishment of Clerical Necromancers During the Period 1100-1500 CE A Thesis Presented to the Academic Faculty by Kayla Marie McManus-Viana In Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in History, Technology, and Society with the Research Option Georgia Institute of Technology December 2020 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Abstract Section 2: Introduction Section 3: Literature Review Section 4: Historical Background Magic in the Middle Ages What is Necromancy? Clerics as Sorcerers The Catholic Church in the Middle Ages The Law and Magic Section 5: Case Studies Prologue: Magic and Rhetoric The Cases Section 6: Conclusion Section 7: Bibliography 3 Abstract “The power of Christ compels you!” is probably the most infamous line from the 1973 film The Exorcist. The movie, as the title suggests, follows the journey of a priest as he attempts to excise a demon from within the body of a young girl. These types of sensational pop culture depictions are what inform the majority of people’s conceptions of demons and demonic magic nowadays. Historically, however, human conceptions of demons and magic were more nuanced than those depicted in The Exorcist and similar works. Demons were not only beings to be feared but sources of power to be exploited. Necromancy, a form of demonic magic, was one avenue in which individuals could attempt to gain control over a demon. During the period this thesis explores, 1100-1500 CE, only highly educated men, like clerics, could complete the complicated rituals associated with necromancy. Thus, this study examines the rise of the learned art of clerical necromancy in conjunction with the re-emergence of higher learning in western Europe that developed during the period from 1100-1500 CE. -

Ryan Murphy Final

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘AMERICAN HORROR STORY’ & ‘GLEE’ CO-CREATOR & EXECUTIVE PRODUCER RYAN MURPHY JOINS SPEAKERS LINEUP FOR PROMAXBDA CONFERENCE IN LOS ANGELES JUNE 12-14, 2012 LOS ANGELES, CA – May 30, 2012 - PromaxBDA, the leading global association for promotion, marketing and design professionals in the entertainment industry, today announced that Emmy and Golden Globe Award-winning director Ryan Murphy of FX’S ‘American Horror Story’ & FOX Broadcasting Company’s “Glee” will join the speaker roster for The Conference 2012, June 12-14 in Los Angeles. “Few who have had such a seismic, global impact on television, film and storytelling are as dedicated and involved in marketing and promotion as Ryan Murphy,” said Jonathan Block-Verk, president and CEO of PromaxBDA International. “We are delighted that he will share some of his most valued experiences and insights with the 2012 PromaxBDA audience.” Ryan Murphy is currently the co-creator, executive producer, writer and director on the acclaimed FX series “American Horror Story” as well as the Fox smash hit “Glee.” As an Emmy Award-winning director for “Glee,” Murphy has also received five Emmy Award nominations. He is the Golden Globe Award-winning creator, writer and director of FX’s original drama series “Nip/Tuck” and the Screen Actors Guild, Emmy and Golden Globe Award-winning Fox series, “Glee.” In his session, he will talk about what inspires him and drives a show’s success, and provide insight on his experience and involvement with marketing and promotion on all of his productions. Murphy’s FX hit series “American Horror Story,” premiered in 2011 to the highest-ever ratings for an FX freshman series. -

Charms, Charmers and Charming Российский Государственный Гуманитарный Университет Российско-Французский Центр Исторической Антропологии Им

Charms, Charmers and Charming Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Российско-французский центр исторической антропологии им. Марка Блока Институт языкознания РАН Институт славяноведения РАН Заговорные тексты в структурном и сравнительном освещении Материалы конференции Комиссии по вербальной магии Международного общества по изучению фольклорных нарративов 27–29 октября 2011 года Москва Москва 2011 Russian State University for the Humanities Marc Bloch Russian-French Center for Historical Anthropology Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Slavic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences Oral Charms in Structural and Comparative Light Proceedings of the Conference of the International Society for Folk Narrative Research’s (ISFNR) Committee on Charms, Charmers and Charming 27–29th October 2011 Moscow Moscow 2011 УДК 398 ББК 82.3(0) О 68 Publication was supported by The Russian Foundation for Basic Research (№ 11-06-06095г) Oral Charms in Structural and Comparative Light. Proceedings of the Con- ference of the International Society for Folk Narrative Research’s (ISFNR) Committee on Charms, Charmers and Charming. 27–29th October 2011, Mos- cow / Editors: Tatyana A. Mikhailova, Jonathan Roper, Andrey L. Toporkov, Dmitry S. Nikolayev. – Moscow: PROBEL-2000, 2011. – 222 p. (Charms, Charmers and Charming.) ISBN 978-5-98604-276-3 The Conference is supported by the Program of Fundamental Research of the De- partment of History and Philology of the Russian Academy of Sciences ‘Text in Inter- action with Social-Cultural Environment: Levels of Historic-Literary and Linguistic Interpretation’. Заговорные тексты в структурном и сравнительном освещении. Мате- риалы конференции Комиссии по вербальной магии Международного об- щества по изучению фольклорных нарративов. 27–29 октября 2011 года, Москва / Редколлегия: Т.А.