USHMM Finding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ost- U. Westpreußen Resources (Including Danzig) at the IGS Library

Ost- u. WestPreußen Resources (including Danzig) at the IGS Library Introduction to East & West Prussia and Danzig The Map Guide to German Parish Registers series has five volumes devoted to this region, #44 through #48. The first two cover West Prussia, with #44 devoted to the Regierungsbezirk Danzig and #45 the RB Marienwerder. The last three are for East Prussia, and deal with RB Allenstein, RB Königsberg and RB Gumbinnen, respectively. A note from Mark F. Rabideau on OW-Preussen-L for 1 June 2015: As for the broader situation regarding Pommern records, I would guess there is a about a 80-90% record loss due to WW2 It is truly bleak. Westpreussen fared somewhat better; the record loss there is more on the order of ~40% across that former region. The bottom line is that the LDS records are most likely your best record source (currently). It may be that archion will eventually provide (in the future) some currently unavailable records (but that is hard to know for certain). See: http://wiki-de.genealogy.net/Archion Region-wide Resources Online Research in former (pre-1945) German lands — http://www.heimat-der-vorfahren.de [O/W] Prussian Antiquarian Society (German) — http://www.prussia-gesellschaft.de Society: Verein für Familienforschung in O/WPr. — http://www.vffow.de/default.htm [To enter the online databases, Login Name = “Gast” & Passwort = “vffow”.] (former) East German Gen. Assoc. (German) — http://www.agoff.de German-Baltic Gen. Soc. (German) — http://www.dbgg.de/index.htm Researching Germans in today’s Poland — http://www.unsere-ahnen.de Forum on former areas — http://forum.ahnenforschung.net/archive/index.php/f-43.html Forum topics organized by Kreis — http://www.deutscheahnen.de/forum/ Placename listings — http://www.schuka.net/FamFo/HG/orte_a.htm http://www.schuka.net/FamFo/HG/Aemter-OWP.htm Placenames, translations from German to present-day Polish — https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_deutscher_Bezeichnungen_polnischer_Orte Family names — http://forum.naanoo.com/freeboard/board/index.php?userid=21893 Scots in E. -

Protection of Minorities in Upper Silesia

[Distributed to the Council.] Official No. : C-422. I 932 - I- Geneva, May 30th, 1932. LEAGUE OF NATIONS PROTECTION OF MINORITIES IN UPPER SILESIA PETITION FROM THE “ASSOCIATION OF POLES IN GERMANY”, SECTION I, OF OPPELN, CONCERNING THE SITUATION OF THE POLISH MINORITY IN GERMAN UPPER SILESIA Note by the Secretary-General. In accordance with the procedure established for petitions addressed to the Council of the League of Nations under Article 147 of the Germano-Polish Convention of May 15th, 1922, concerning Upper Silesia, the Secretary-General forwarded this petition with twenty appendices, on December 21st, 1931, to the German Government for its observations. A fter having obtained from the Acting-President of the Council an extension of the time limit fixed for the presentation of its observations, the German Government forwarded them in a letter dated March 30th, 1932, accompanied by twenty-nine appendices. The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate, for the consideration of the Council, the petition and the observations of the German Government with their respective appendices. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page I Petition from the “Association of Poles in Germany”, Section I, of Oppeln, con cerning the Situation of the Polish Minority in German Upper Silesia . 5 A ppendices to th e P e t i t i o n ................................................................................................................... 20 II. O bservations of th e G erm an G o v e r n m e n t.................................................................................... 9^ A ppendices to th e O b s e r v a t i o n s ...............................................................................................................I03 S. A N. 400 (F.) 230 (A.) 5/32. -

Village German

Village Polish, Lithuanian, Village German (Village today), Powiat today, Woiwodschaft today, Country North East Russian County German Province German Abelischken/Ilmenhorst (Belkino), Pravdinsk, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 542529 213708 Белкино Gerdauen Ostpreussen Ablenken (Oplankys), , Taurage, German Empire (Lithuania) 551020 220842 Oplankys Tilsit Ostpreussen Abschermeningken/Almental (Obszarniki), Goldap, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 542004 220741 Obszarniki Darkehmen Ostpreussen Abschwangen (Tishino), Bagrationovsk, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 543000 204520 Тишино Preussisch Eylau Ostpreussen Absteinen (Opstainys), Pagegiai, Taurage, German Empire (Lithuania) 550448 220748 Opstainys Tilsit Ostpreussen Absteinen (W of Chernyshevskoye), Nesterov, Kaliningrad, German Empire (Russia) 543800 224200 Stallupoenen Ostpreussen Achodden/Neuvoelklingen (Ochodno), Szczytno, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 533653 210255 Ochódno Ortelsburg Ostpreussen Achthuben (Pieszkowo), Bartoszyce , Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German Empire (Poland) 541237 203008 Pieszkowo Mohrungen Ostpreussen Adamsdorf (Adamowo), Brodnica, Kujawsko‐Pomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 532554 190921 Adamowo Strasburg I. Westpr. Westpreussen Adamsdorf (Maly Rudnik), Grudziadz, Kujawsko‐Pomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 532440 184251 Mały Rudnik Graudenz Westpreussen Adamsdorf (Sulimierz), Mysliborz, Zachodniopomorskie, German Empire (Poland) 525754 150057 Sulimierz Soldin Brandenburg Adamsgut (Jadaminy), Olsztyn, Warminsko‐Mazurskie, German -

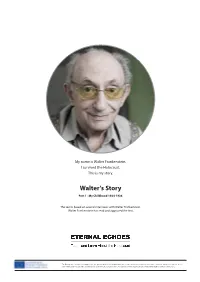

Walter's Story

Walter’s Story My name is Walter Frankenstein. I survived the Holocaust. This is my story. Walter’s Story Part 1 · My Childhood 1924-1936 The text is based on several interviews with Walter Frankenstein. Walter Frankenstein has read and approved the text. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. 1 Walter’s Story My Childhood 1924-1936 My Family I come from a small town called Flatow. When I grew up, the town was located in northeastern Germany in what was then known as West Prussia. The entire province became a part of Poland after the Second World War. My father was called Max Frankenstein. His step-parents managed a general store and a tavern in Flatow, and father and his wife later took over the business. They had a son, Manfred, in 1910. A couple of years later, in 1914, they had twins. One of the children died but Martin survived. A while later their mother died from blood poisoning after opening a tin and cutting herself on the lid. My father met my own mother, Martha, in 1923. At the time, she was living with her parents in Braunsberg. She moved to Flatow when they married, and I was born one year later on 30 June 1924. When I was four years old, my father died of pneumonia and heart failure. -

Verdrängen Und Wiederentdecken

STUDIEN zur Ostmitteleuropaforschung 36 Katarzyna Woniak Verdrängen und Wiederentdecken Die Erinnerungskulturen in den west- und nord- polnischen Kleinstädten Labes und Flatow seit 1945. Eine vergleichende Studie Katarzyna Woniak, Verdrängen und Wiederentdecken. Die Erinnerungskulturen in den west- und nordpolnischen Kleinstädten Labes und Flatow seit 1945. Eine vergleichende Studie STUDIEN ZUR OSTMITTELEUROPAFORSCHUNG Herausgegeben vom Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft 36 Katarzyna Woniak Verdrängen und Wiederentdecken Die Erinnerungskulturen in den west- und nord- polnischen Kleinstädten Labes und Flatow seit 1945. Eine vergleichende Studie VERLAG HERDER-INSTITUT · MARBURG · 2016 Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar Diese Publikation wurde einem anonymisierten Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. This publication has undergone the process of anonymous, international peer review. Deutsch-polnische Disputation am 23.11.2012 an der Adam-Mickiewicz-Universität Posen. © 2016 by Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft, 35037 Marburg, Gisonenweg 5-7 Printed in Germany Alle Rechte vorbehalten Satz: Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft, 35037 Marburg Druck: KN Digital Printforce -

Culture and Exchange: the Jews of Königsberg, 1700-1820

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2010 Culture and Exchange: The ewJ s of Königsberg, 1700-1820 Jill Storm Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Storm, Jill, "Culture and Exchange: The eJ ws of Königsberg, 1700-1820" (2010). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 335. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/335 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of History Dissertation Examination Committee: Hillel Kieval, Chair Matthew Erlin Martin Jacobs Christine Johnson Corinna Treitel CULTURE AND EXCHANGE: THE JEWS OF KÖNIGSBERG, 1700-1820 by Jill Anita Storm A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 Saint Louis, Missouri Contents Acknowledgments ii Introduction 1 Part One: Politics and Economics 1 The Founding of the Community 18 2 “A Watchful Eye”: Synagogue Surveillance 45 3 “Corner Synagogues” and State Control 81 4 Jewish Commercial Life 115 5 Cross-Cultural Exchange 145 Part Two: Culture 6 “A Learned Siberia”: Königsberg’s Place in Historiography 186 7 Ha-Measef and the Königsberg Haskalah 209 8 Maskil vs. Rabbi: Jewish Education and Communal Conflict 232 9 The Edict of 1812 272 Conclusion 293 Bibliography 302 Acknowledgments Many people and organizations have supported me during this dissertation. -

Zapiski Historyczne

TOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE W TORUNIU WYDZIAŁ NAUK HISTORYCZNYCH BIBLIOTEKA UNIWERSYTECKA W TORUNIU ZAPISKI HISTORYCZNE POŚWIĘCONE HISTORII POMORZA I KRAJÓW BAŁTYCKICH TOM LXXIV – ROK 2009 SUPLEMENT BIBLIOGRAFIA HISTORII POMORZA WSCHODNIEGO I ZACHODNIEGO ORAZ KRAJÓW REGIONU BAŁTYKU ZA ROK 2007 Toruń 2009 BIBLIOGRAFIA HISTORII POMORZA WSCHODNIEGO I ZACHODNIEGO oraz KRAJÓW REGIONU BAŁTYKU ZA ROK 2007 wraz z uzupełnieniami z lat poprzednich Opracowali URSZULA ZABORSKA i ADAM BIEDRZYCKI współpraca Gabriele Kempf i Norbert Kersken (Marburg) RADA REDAKCYJNA ZAPISEK HISTORYCZNYCH Przewodniczący: Marian Biskup Członkowie: Stefan Cackowski, Karola Ciesielska, Antoni Czacharowski, Jacek Staszewski, Kazimierz Wajda KOMITET REDAKCYJNY ZAPISEK HISTORYCZNYCH Redaktor: Bogusław Dybaś Członkowie: Roman Czaja, Jerzy Dygdała, Magdalena Niedzielska, Mieczysław Wojciechowski Sekretarze Redakcji: Paweł A. Jeziorski, Katarzyna Minczykowska Skład i łamanie: WENA Włodzimierz Dąbrowski Adres Redakcji Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu 87100 Toruń, ul. Wysoka 16 www.tnt.torun.pl/zapiski email: [email protected] Instrukcja dla autorów znajduje się na stronie internetowej oraz w każdym zeszycie pierwszym czasopisma Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in „Historical Abstracts” Wydanie publikacji dofi nansowane przez Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego ISSN 00441791 TOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE W TORUNIU Wydanie I. Ark. wyd. 24,7 Ark. druk. 19 Wąbrzeskie Zakłady Grafi czne Wąbrzeźno, ul. Mickiewicza 15 SPIS TREŚCI A. Ogólne I. Bibliografi e ..............................................................................................................................7 -

Genealogy of William Remus

The Remus Family of West Prussia: Volume II Part I The period around 1700 was not a good time for West Prussia. The Great Northern Wars taking place then led to warfare and destruction resulting in perhaps the loss of a third of the population. To repopulate their land (and generate profits), the Polish nobility sold the right to manage villages (called schultz privilege) and the right to mill grain to Germans. Thus, my ancestors entered West Prussia following the demobilization of the Saxon Army circa 1717. It is important to note that the Remus family of Kamenz were burgers (see the earlier section on Kamenz) and thus had some assets with which to acquire schultz privileges. This was the top tier of peasants although definitely superseded by the nobility. The first reference to the schultzes and millers in Remus family in West Prussia was in August Blanke's "Aus Vergangenen Tagen des Kreises Schlochau" (1936) where Johan Remus was said to be a miller in Rogonitza, the mill for Bergelau, and to a lesser extent Pollnitz, Kreis Schlochau around 1700. The article goes on to explain that Johan Remus sold the mill to Andreas Rogosznicki around 1720. Otto Goerke's "Der Kreis Flatow" reports that Johan Remus purchased the schultz privilege and the schultzengut in Lanken, Kreis Flatow in 1714 (that is, the right to administer a village and a manorial farm for the villagers to work on). The Johan Remus family also had the schultz privileg for Aspenau (Ossowo) in Kreis Flatow. An article by Walter Tesmer states that the Remus family was an old established family in the Kreis Flatow area by 1706. -

Warsaw. the Jewish Metropolis

Warsaw. The Jewish Metropolis Frontispiece Bernardo Belotto, known as Canaletto, Bridgettine Church and the Arsenal, 1775. Detail presenting Jews standing in front of a small manor house on the corner of Długa and Bielańska streets, Royal Castle in Warsaw ( fot. Andrzej Ring). IJS STUDIES IN JUDAICA Conference Proceedings of the Institute of Jewish Studies, University College London Series Editors Mark Geller François Guesnet Ada Rapoport-Albert VOLUME 15 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ijs Warsaw. The Jewish Metropolis Essays in Honor of the 75th Birthday of Professor Antony Polonsky Edited by Glenn Dynner and François Guesnet LEIDEN | BOSTON Warsaw. the Jewish metropolis : essays in honor of the 75th birthday of professor Antony Polonsky / edited by Glenn Dynner and François Guesnet. pages cm. — (IJS studies in Judaica ; volume 15) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-29180-5 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-29181-2 (e-book) 1. Jews—Poland— Warsaw—History. 2. Jews—Poland—Warsaw—Social conditions—History. 3. Jews—Poland— Warsaw—Economic conditions—History 4. Jews—Poland—Warsaw—Intellectual life. 5. Warsaw (Poland)—Ethnic relations. I. Dynner, Glenn, 1969- editor. II. Guesnet, François, editor. III. Polonsky, Antony, honoree. IV. Title: Jewish metropolis. DS134.64.W36 2015 305.892’4043841—dc23 2015005127 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1570-1581 isbn 978-90-04-29180-5 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-29181-2 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Annotationen. Neuerscheinungen Aus Ostmitteleuropa

Annotationen. Neuerscheinungen aus Ostmitteleuropa Vorbemerkung Die folgenden bibliographischen Anzeigen beziehen sich auf in den Staaten Ostmit- tel-, Nordost- und Südosteuropas erschienene Literatur (Monographien, Sammel- bände, Zeitschriften und Reihen, Editionen) aus den Wissenschaftsbereichen Ge- schichte, Kunstgeschichte, Volkskunde / Europäische Ethnologie und Germanistik. Berücksichtigt sind Titel, die die Kultur und Geschichte der ehemaligen deutschen Ostgebiete sowie der Siedlungsgebiete der Deutschen im östlichen Europa (mit-) betreffen. Um den interdisziplinären Charakter der Rubrik zu betonen, sind die „Annotationen“ wie in den Vorjahren nicht nach Fachgebieten, sondern nach den folgenden – zum Teil historischen – Regionen angeordnet, wobei gelegentliche Pro- bleme bei der regionalen Zuordnung und Abgrenzung unvermeidlich sind: 1. Regional übergreifende Werke, 2. Baltikum, 3. Ostpreußen, Westpreußen, Danzig, 4. Pommern, Neumark, 5. Schlesien, 6. Großpolen, Zentralpolen, Kleinpolen, 7. Böhmen, Mähren, 8. Slowakei, 9. Ungarn, Rumänien, 10. Slowenien, Kroatien, Serbien, 11. Russland, Ukraine. Bei Sammel- oder Zeitschriftenbänden werden, von Ausnahmen abgesehen, ledig- lich die Beiträge zu den einschlägigen Themenbereichen ,Deutsche im östlichen Eu- ropa‘ und ,deutsch-ostmitteleuropäische Beziehungen‘ angeführt. Übersetzungen von bereits in deutscher Sprache publizierten Titeln wurden in der Regel nur dann aufgenommen, wenn sie gegenüber der Originalfassung eine inhaltliche Erweite- rung, etwa durch ein wissenschaftliches Nachwort, -

Piła (Schneidemuhl) Czy Frankfurt Nad Odrą? Spór O Nową Stolicę

uniwersytet zielonogórski studia zachodnie 16 • zie lo na góra 2014 Olgierd Kiec Zielona Góra PiłA (SChneiDemÜhl) Czy FrankFurt naD ODRą? SPÓR O nową stolicę niemieCkieJ MarChii WSChoDnieJ (Ostmark) W lataCH 1919-1939 „W przestrzeni czas czytamy” – tym zdaniem Friedricha Ratzela zatytułował Karl Schlögel zbiór swoich esejów poświęconych przemianom, jakim podlega postrzeganie, przedstawianie i objaśnianie przestrzeni1 . Nie było zapewne przypadkiem, że problem ten podjął niemiecki historyk Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej, gdyż przedstawiciele tej specjalności znakomicie rozumieją dyskusje na temat nacjonalizmu niemieckiego oraz przebiegu granicy Niemiec; jak trafnie zauważył Dirk van Laak, przestrzenie – ale także historie – najlepiej rekonstruuje się, zaczynając od peryferii2 . Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland? (Gdzież jest ojczyzna Niemca?) pytał w 1813 roku Ernst Moritz Arndt, a pytanie to bynajmniej nie straciło aktualności po zjednoczeniu Niemiec w 1871 roku (choćby z powodu pozostawienia poza granicami Rzeszy Wiednia i Niemców austriackich) . Jak wskazywał wspomniany van Laak, niepewność co do tego, gdzie leżą Niemcy i jak się powinno ów kraj definiować, nurtowała jego mieszkańców przez cały okres ich narodowych dziejów, osiągając szczególnie zapalny i konfliktogenny wymiar tam, gdzie trzeba było wytyczyć nie tylko granice geograficzne i polityczne, ale także językowe i kulturowe3 . Takim konfliktogennym obszarem były niewątpliwie wschodnie prowincje Prus, które od 1871 roku tworzyły również wschodnią rubież Rzeszy Niemieckiej . To w tych prowincjach proces kształtowania się narodu niemieckiego zachodził w szczególnych warunkach – nie tylko z powodu granicy politycznej z Rosją, ale także z racji codziennej konfrontacji z polskimi poddanymi pruskiego króla i niemieckiego cesarza . Sąsiedztwo wschodniosłowiańskiego mocarstwa Romanowów z jego polską buntowniczą mniejszo- ścią i jednocześnie obecność liczącej ponad 3 miliony polskiej mniejszości w granicach monarchii Hohenzollernów określiły szczególną pozycję wschodnich prowincji Prus 1 K . -

Political and Transitional Justice in Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930S to the 1950S

Political and Transitional Justice in Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the 1950s Political and Transitional Justice in Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union from the 1930s to the 1950s Edited by Magnus Brechtken, Władysław Bułhak and Jürgen Zarusky We dedicate this volume to the memory of Arseni Borisovich Roginsky (1946-2017), the co-founder and long-time chairman of the board of Memorial, and to the memory of Jürgen Zarusky (1958-2019), who dedicated his academic life to the research on historical and political justice and inspired this volume. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Der Band wird im Open Access unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 auf dem Dokumentenserver »Zeitgeschichte Open« des Instituts für Zeitgeschichte München-Berlin bereitgestellt (https://doi.org/10.15463/ifz-2019-1). Die Veröffentlichung wurde durch den Open-Access-Publikationsfonds für Monografien der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft gefördert. © Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2019 www.wallstein-verlag.de Vom Verlag gesetzt aus der Adobe Garamond Umschlaggestaltung: Susanne Gerhards, Düsseldorf unter Verwendung zeitgenös- sischer Illustrationen. Von oben nach unten: Standbild aus der Aufnahme des Dritten Moskauer Schauprozess 1938, https://vimeo.com/147767191; Volksgerichtshof, Prozeß nach dem 20. Juli 1944, © Bundesarchiv, Bild 151-39-23 / CC-BY-SA 3.0; Prozess gegen Priester in Krakau (Proces księży Kurii Krakowskiej), Zygmunt Wdowiński 1953 © CAF, Polska Agencja Prasowa S.A. ISBN (Print) 978-3-8353-3561-5 Contents Magnus Brechtken, Władysław Bułhak and Jürgen Zarusky (†) Introduction .