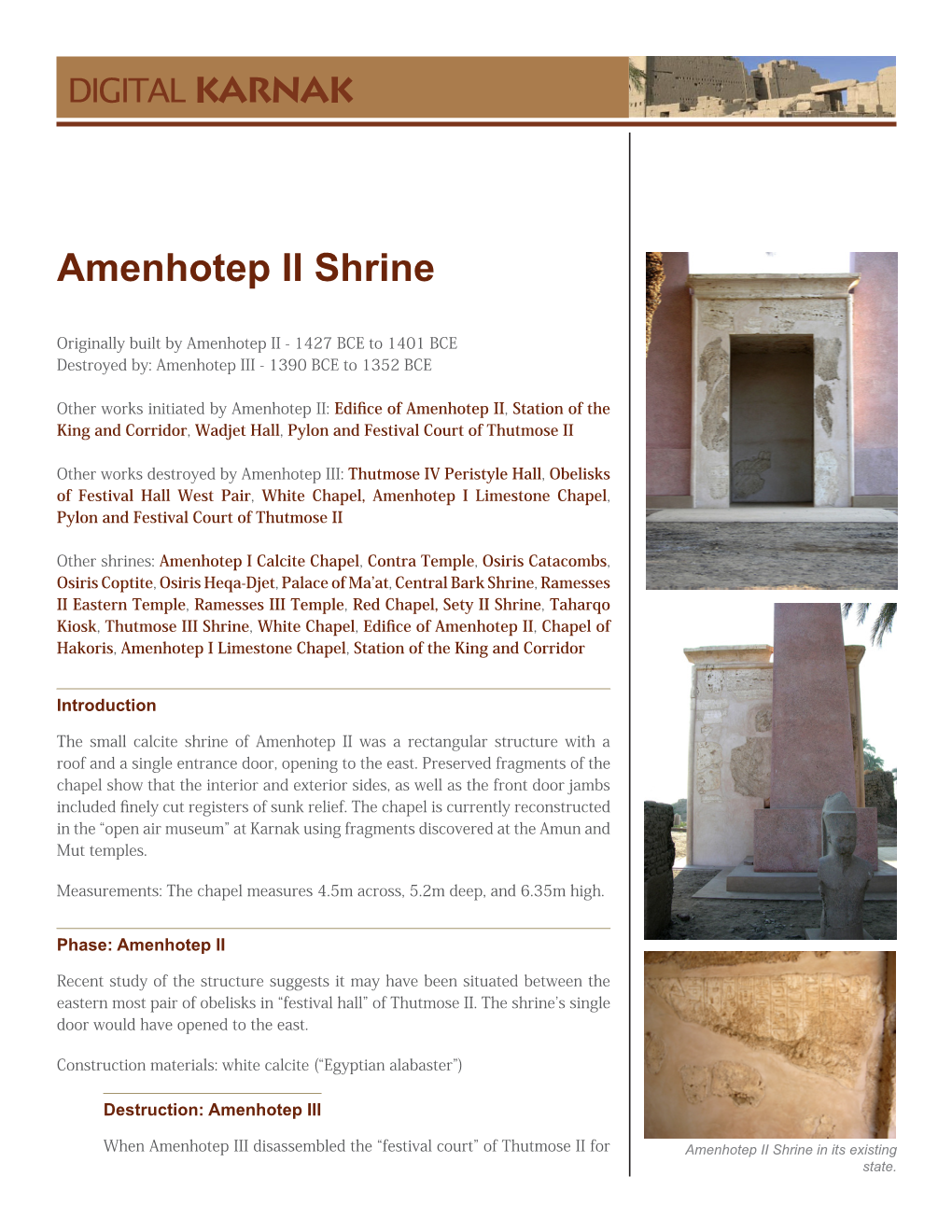

Amenhotep II Shrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canaan Or Gaza?

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza? Michael G. Hasel Institute of Archaeology, Southern Adventist University A&564%'6 e identification of the geographical name “Canaan” continues to be widely debated in the scholarly literature. Cuneiform sources om Mari, Amarna, Ugarit, Aššur, and Hattusha have been discussed, as have Egyptian sources. Renewed excavations in North Sinai along the “Ways of Horus” have, along with recent scholarly reconstructions, refocused attention on the toponyms leading toward and culminating in the arrival to Canaan. is has led to two interpretations of the Egyptian name Pa-Canaan: it is either identified as the territory of Canaan or the city of Gaza. is article offers a renewed analysis of the terms Canaan, Pa-Canaan, and Canaanite in key documents of the New Kingdom, with limited attention to parallels of other geographical names, including Kharu, Retenu, and Djahy. It is suggested that the name Pa-Canaan in Egyptian New Kingdom sources consistently refers to the larger geographical territory occupied by the Egyptians in Asia. y the 1960s, a general consensus had emerged regarding of Canaan varied: that it was a territory in Asia, that its bound - the extent of the land of Canaan, its boundaries and aries were fluid, and that it also referred to Gaza itself. 11 He Bgeographical area. 1 The primary sources for the recon - concludes, “No wonder that Lemche’s review of the evidence struction of this area include: (1) the Mari letters, (2) the uncovered so many difficulties and finally led him to conclude Amarna letters, (3) Ugaritic texts, (4) texts from Aššur and that Canaan was a vague term.” 12 Hattusha, and (5) Egyptian texts and reliefs. -

ROYAL STATUES Including Sphinxes

ROYAL STATUES Including sphinxes EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD Dynasties I-II Including later commemorative statues Ninutjer 800-150-900 Statuette of Ninuter seated wearing heb-sed cloak, calcite(?), formerly in G. Michaelidis colln., then in J. L. Boele van Hensbroek colln. in 1962. Simpson, W. K. in JEA 42 (1956), 45-9 figs. 1, 2 pl. iv. Send 800-160-900 Statuette of Send kneeling with vases, bronze, probably made during Dyn. XXVI, formerly in G. Posno colln. and in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, in 1883, now in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 8433. Abubakr, Abd el Monem J. Untersuchungen über die ägyptischen Kronen (1937), 27 Taf. 7; Roeder, Äg. Bronzefiguren 292 [355, e] Abb. 373 Taf. 44 [f]; Wildung, Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt i, 51 [Dok. xiii. 60] Abb. iv [1]. Name, Gauthier, Livre des Rois i, 22 [vi]. See Antiquités égyptiennes ... Collection de M. Gustave Posno (1874), No. 53; Hôtel Drouot Sale Cat. May 22-6, 1883, No. 53; Stern in Zeitschrift für die gebildete Welt 3 (1883), 287; Ausf. Verz. 303; von Bissing in 2 Mitteilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung xxxviii (1913), 259 n. 2 (suggests from Memphis). Not identified by texts 800-195-000 Head of royal statue, perhaps early Dyn. I, in London, Petrie Museum, 15989. Petrie in Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland xxxvi (1906), 200 pl. xix; id. Arts and Crafts 31 figs. 19, 20; id. The Revolutions of Civilisation 15 fig. 7; id. in Anc. Eg. (1915), 168 view 4; id. in Hammerton, J. A. -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

The Image of the 'Warrior Pharaoh'

The image of the ‘warrior pharaoh’ The mighty ‘warrior pharaoh’ is one of the most enduring images of ancient Egypt and dates to the beginnings of Egyptian civilisation around 3000 BC . It was both a political and a religious statement and emphasised the king’s role as the divine upholder of maat, the Egyptian concept of order. The king is shown triumphing over the forces of chaos, represented by foreign enemies and bound captives. In earlier times, the king, a distant and mysterious being, was held in godlike awe by his subjects. However, by New Kingdom times he was a more earthly, vulnerable figure who fought alongside his troops in battle. The militarism of the New Kingdom gave birth to a new heroic age. To the traditional elements of the warrior pharaoh image was added the chariot, one of the most important innovations of this period. The essential features of the New Kingdom ‘warrior pharaoh’ image include the pharaoh: • leading his soldiers into battle and returning in victory • attacking the enemy while riding in his chariot • wearing war regalia, for example, the blue war crown or other pharaonic headdress • depicted larger than life-size, holding one or more of the enemy with one hand, while he clubs their brains out with a mace (also known as ‘smiting the enemy’) • in the guise of a sphinx, trampling his enemies underfoot • offering the spoils of war to the god Amun, the inspiration for his victory. FIGURE 21 Thutmose III smiting the enemy Another aspect of the warrior pharaoh image that developed over time was the pharaoh as elite athlete and sportsman, a perfect physical specimen. -

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the Death of Thutmose IV End of 17Th Dynasty, Egyptians Were Confined to Upper

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the death of Thutmose IV End of 17th dynasty, Egyptians were confined to Upper Egypt, surrounded by Nubia and Hyksos → by the end of the 18th dynasty they had extended deep along the Mediterranean coast, gaining significant economic, political and military strength 1. Internal Developments ● Impact of the Hyksos Context - Egypt had developed an isolated culture, exposing it to attack - Group originating from Syria or Palestine the ‘Hyksos’ took over - Ruled Egypt for 100 years → est capital in Avaris - Claimed a brutal invasion (Manetho) but more likely a gradual occupation - Evidence says Hyksos treated Egyptians kindly, assuming their gods/customs - Statues of combined godes and cultures suggest assimilation - STILL, pharaohs resented not having power - Portrayed Hyksos as foot stools/tiptoe as unworthy of Egyptian soil - Also realised were in danger of being completely overrun - Kings had established a tribune state but had Nubians from South and Hyksos from North = circled IMMEDIATE & LASTING IMPACT OF HYKSOS Political Economic Technological - Administration - Some production - Composite bow itself was not was increased due - Horse drawn oppressive new technologies chariot - Egyptians were - Zebu cattle suited - Bronze weapons climate better - Bronze armour included in the - Traded with Syria, - Fortification administration Crete, Nubia - Olive/pomegranat - Modelled religion e trees on Egyptians - Use of bronze - Limited instead of copper = disturbance to more effective culture/religion/d -

WHO WAS WHO AMONG the ROYAL MUMMIES by Edward F

THE oi.uchicago.edu ORIENTAL INSTITUTE NEWS & NOTES NO. 144 WINTER 1995 ©THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO WHO WAS WHO AMONG THE ROYAL MUMMIES By Edward F. Wente, Professor, The Oriental Institute and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations The University of Chicago had an early association with the mummies. With the exception of the mummy of Thutmose IV, royal mummies, albeit an indirect one. On the Midway in the which a certain Dr. Khayat x-rayed in 1903, and the mummy area in front of where Rockefeller Chapel now stands there of Amenhotep I, x-rayed by Dr. Douglas Derry in the 1930s, was an exhibit of the 1893 World Columbian Exposition known none of the other royal mummies had ever been radiographed as "A Street in Cairo." To lure visitors into the pavilion a plac until Dr. James E. Harris, Chairman of the Department of Orth ard placed at the entrance displayed an over life-sized odontics at the University of Michigan, and his team from the photograph of the "Mummy of Rameses II, the Oppressor of University of Michigan and Alexandria University began x the Israelites." Elsewhere on the exterior of the building were raying the royal mummies in the Cairo Museum in 1967. The the words "Royal Mummies Found Lately in Egypt," giving inadequacy of Smith's approach in determining age at death the impression that the visitor had already been hinted at by would be seeing the genuine Smith in his catalogue, where mummies, which only twelve he indicated that the x-ray of years earlier had been re Thutmose IV suggested that moved by Egyptologists from a this king's age at death might cache in the desert escarpment have been older than his pre of Deir el-Bahri in western vious visual examination of the Thebes. -

A Contemporary of King Amenhotep II at Karnak

CENTRE FRANCO-ÉGYPTIEN D’ÉTUDE DES TEMPLES DE KARNAK LOUQSOR (ÉGYPTE) USR 3172 du Cnrs Extrait des Cahiers de Karnak 5, 1975. Avec l’aimable autorisation de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (Ifao). Courtesy of Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (Ifao). A CONTEMPORAR y OF KING AMENHOTEP II AT KARNAK B.V. BOTHMER When an ancient Egyptian head is found at Karnak, the event seems to be as little newsworthy as when another Old Kingdom mastaba is uncovered at Saqqara. But when the newly discovered head is nearly intact and of unusual quality, it deserves to be promptly made known. The present note, in anticipation of a longer study, is intended merely to introduce the head to those interested in the art of ancient Egypt (1). The head was found in 1972 in the doorway of the north gate of the First Court at Karnak, about 1.20 m. below ground level (pl. XXXIX-XL, A-C). The sculpture, in crystal-speckled gray granite, represents a man with a wide, striated wig and a fairly long plain beard which is preserved intact for its entire length, inc1uding the fini shed underside. The face is idealizing, ageless, and with its c1ear and open features represents the best of which is c1assical in Egyptian art. The face is carved in three planes, a central portion consisting of nose and mouth and part of the eyes, and two sides encompassing most of the cheeks, the outer parts of the eyes and the summarily modeled ears. One is not much aware of this angular arrangement of the features until one studies the eye and realizes that it is really carved in two planes, with the result that the profile view reveals an unusually large portion of the eyeball. -

Ancient Egyptian Life Map for the Valley of the Kings

Ancient Egyptian Life Map for the Valley of the Kings The Valley of the Kings is where all the great pharaohs are buried. There is also the lesser known KV1 Valley of the Queens, where the wives, princes and princesses are buried, as well as some noble people. The Valley of the Kings is near the city of Thebes, now called Luxor. One of Napoleon Bonaparte’s expeditions came across the valley in 1799. Pharaoh Ramesses VII Since then, 63 different tombs have been found there. Some of them go down into the earth 650 feet. Most are richly adorned with paintings and carvings of life in Egypt and Egyptian beliefs of afterlife with the gods. The most famous tomb discovered was that of King Tutenkhamun. Compared to other tombs his was tiny, KV7 and it was undisturbed by grave robbers. Around the 18th dynasty Egyptians left Pharaoh Ramesses II behind building pyramids to carving tombs into the cliffsides of the valley. It is not known why the use of pyramids as burial tradition stopped. KV62 Some Egyptologists think that the valley was started by Queen Hatshepsut. Tutankhamun What do you think? What factors could affect a decision to abandon burying leaders and statesmen in pyramids, or, what might be the appeal of using the cliffs, if any? KV35 Amenhotep II was a succesful military leader during Egypt’s 18th dynasty. Pharaoh Amenhotep II King Tut ascended the throne still a child; his reign returned the country to polytheistic religion and away from his father’s institution of the one sun god. -

The New Kingdom and Its Aftermath

A Short History of Egypt Part III: The New Kingdom and its Aftermath Shawn C. Knight Spring 2009 (This document last revised February 3, 2009) 1 The Early Eighteenth Dynasty The expulsion of the Hyksos was completed by Ahmose, thought by most Egyptologists to be the son of Seqenenre Ta'o II and the younger brother of Kamose. Ahmose brought order and unity to Egypt once more and drove the ruling Hyksos Fifteenth and Sixteenth Dynasties out of the land. He also gave great honors to the women of his family: his mother Queen Tetisheri, and his wife Queen Ahmose-Nefertari were regarded highly for generations to come. His son Amenhotep I, together with Ahmose-Nefertari, was actually worshipped as a god centuries later, as the protector of the royal cemeteries near Thebes. Amenhotep was succeeded by Thutmose I, who abandoned the Seventeenth Dynasty cemetery at Dra Abu el Naga in favor of a nearby valley. Thutmose's architect Ineni recorded that \I supervised the excavation of the cliff tomb of His Majesty alone, no one seeing, no one hearing."1 The valley became the burial site of choice for the rest of the New Kingdom pharaohs, as well as those courtiers (and even pets) whom they particularly favored, and is known to us today as the Valley of the Kings. Thutmose was succeeded by his son, Thutmose II. When Thutmose II died, he was succeeded by his second wife, Hatshepsut, the stepmother of the young heir, Thutmose III. Hatshepsut is perhaps the best-known of all the female pharaohs, with the possible exception of Cleopatra VII. -

Kawai Transcript.Pdf

Introduction: Welcome to the American Research Center in Egypt’s podcast. Each month, we will bring you the latest findings in Egyptological research and host engaging discussions about fascinating topics in Egyptian cultural heritage. Each of our guests are world renowned scholars in the fields of Egyptology, Islamic, Coptic, and modern Egyptian history, archaeology and much more. To suggest a topic for this program, please email us at [email protected]. We are also available on Apple, Spotify, Google or wherever you may listen to podcasts. If you enjoy this podcast, you can find out more about our other programs and activities, including virtual lectures and tours by visiting our website at arce.org. That's a r c e.org. You can also support our work by joining our mailing list, becoming a member or donating to support this podcast. This month's podcast focuses on King Tutankhamun’s court featuring Dr. Fatma Ismail, ARCE’s US Director of Outreach and Programs in conversation with our guest, Professor Nozomu Kawai of Kanazawa University in Japan. Thank you so much for joining us today and I hope you enjoy the episode. Fatma Ismail: Our guest on today's episode on King Tutankhamun is Professor Nozomu Kawai. He's professor of Egyptology at Kanazawa University, Japan, and the director of the North Saqqara project. His research focuses on the history, art and archaeology of the New Kingdom, Egypt, with a particular emphasis on the period from the late 18th dynasty to the 19th dynasty. He obtained his PhD on the reign of Tutankhamun in 2006 and he's currently working for the revision of his original dissertation for publication. -

Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut

iii OccasiOnal prOceedings Of the theban wOrkshOp creativity and innovation in the reign of hatshepsut edited by José M. Galán, Betsy M. Bryan, and Peter F. Dorman Papers from the Theban Workshop 2010 The OrienTal insTiTuTe OF The universiTy OF ChiCaGO iv The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 2014 by The university of Chicago. all rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the united states of america. series editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban with the assistance of Rebecca Cain Series Editors’ Acknowledgment Brian Keenan assisted in the production of this volume. Cover Illustration The god amun in bed with Queen ahmes, conceiving the future hatshepsut. Traced by Pía rodríguez Frade (based on Édouard naville, The Temple of Deir el Bahari Printed by through Four Colour Imports, by Lifetouch, Loves Park, Illinois USA The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of american national standard for information services — Permanence of Paper v table of contents Preface. José M. Galán, Spanish National Research Council, Madrid ........................................... vii list of abbreviations .............................................................................. xiii Bibliography..................................................................................... xv papers frOm the theban wOrkshOp, 2010 1. innovation at the Dawn of the new Kingdom. Peter F. Dorman, American University of Beirut...................................................... 1 2. The Paradigms of innovation and Their application -

1. INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS Reign of Amenhotep III Background • Son of Thutmose IV and Mutemwia • Thutmose Died When He Was 12

1. INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS Reign of Amenhotep III Background • Son of Thutmose IV and Mutemwia • Thutmose died when he was 12 and Amenhotep was advised by his mother in the early years of his reign • Inherited a reign of great peace and prosperity from his father; had to maintain rather than expand or improve • Married to his Great Royal Wife Tiye by the second year of his reign • Promoted his eldest daughter, Sitamun, to Great Royal Wife • Entered into numerous of marriages with foreign princesses to ensure stable diplomatic relations These scarabs were issues throughout the Empire and boast about his hunting prowess. They promote the stereotypical image of the pharaoh as a great hunter, emphasising his strength and virility. Not always based in fact, but rather an artistic convention which symbolised the king’s fitness to rule and his triumph over the forces of L: Wild bull-hunt commemorative scarab chaos. R: Lion hunt commemorative scarab Building programs • Unprecedented, massive and ostentatious • Overseer or All the King’s Works, Amenhotep, son of Hapu, is behind most of it • Honoured the gods with building projects, but the nature and size of his projects may indicate that he was using the country’s resources to glorify himself Large and impressive. Contains relief showing Amun’s role in the divine birth and coronation of Amenhotep III. Temple of Amun at Luxor Pylons at Karnak Built a new pylon after demolishing the shrines and monuments of earlier pharaohs and using that rubble to fill his pylon. Lengthy inscription praises himself and Amen, and lists the gifts he had given to the temple.