Papua, a Multi-Facetted History Pieter Drooglever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoires 1961

Memoires 1961 Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Memoires 1961. In den Toren, Baarn 1989 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003memo05_01/colofon.php © Stichting Willem Oltmans / dbnl 6 Voor de heer en mevrouw J. van Dijk, directeur Nieuw Baarnse School Willem Oltmans, Memoires 1961 7 Inleiding Door een technische fout ontbraken in het vorige deel (1959-1961) drie dagboekaantekeningen: 18 januari 1961 (dagboek) Penn-Sheraton Hotel, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Tot mijn onsterfelijke ergernis heb ik ongeveer 25 pagina's van mijn dagboek in de Greyhoundbus verloren. Alles is weg, ook de knipsels. Ik was in Chicago geweest en had een lezing in Omaha, Nebraska gegeven. Lunchte met leden van de ‘Ad-Sell Club’ in de Kamer van Koophandel aldaar. Had ook een televisie-interview in Omaha gegeven en een slaapwagen van de Burlington Railroad terug naar Chicago genomen. Gaf vervolgens een lezing in Evaston, Illinois en arriveerde hier met een Greyhoundbus vanuit Chicago. 19 januari 1961 Patrice Lumumba is nu in handen van Moise Tshombe in Katanga, wat me absoluut razend maakt. Zweedse UNO-troepen kwamen niet tussenbeide, toen soldaten van Tshombe de voormalige premier in elkaar sloegen. Hij werd in een jeep gesmeten, nà nog verdere mishandeling. Vier soldaten van Tshombe gingen boven op Lumumba en twee van zijn medestanders zitten. Hij is nu opgesloten in de gevangenis van Jadotville, in het hartje van het koperrijke gebied van Katanga. Ik vrees het ergste. Om 18:30 sprak ik voor de ‘Dutch Treat Club’ in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. 20 januari 1961 Mijn broer Theo schrijft onder meer uit Kaapstad: ‘This country is completely entangled in the most hopeless human relations. -

ASC Working Paper 122 / 2015

Historical overview of development policies and institutions in the Netherlands, in the context of private sector development and (productive) employment creation Agnieszka Kazimierczuk ASC Working Paper 122 / 2015 Agnieszka Kazimierczuk African Studies Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 Fax +31-71-5273344 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.ascleiden.nl Agnieszka Kazimierczuk, 2015 2 Historical overview of development policies and institutions in the Netherlands, in the context of private sector development and (productive) employment creation Agnieszka Kazimierczuk Abstract This paper reviews the Dutch development cooperation policies for the years 1949-2015 with particular attention for private sector development (PSD). Over the years, poverty alleviation, private sector development and security have been dominant focus areas of Dutch development cooperation, with PSD taking a central role as it was assumed that poverty could only be alleviated when a country’s economy is stimulated. Therefore, the Dutch government has been strongly supporting policies and initiatives stimulating PSD in the Netherlands and in developing countries. The long history of Dutch development cooperation shows continuity in its approach towards development policy as a way of promoting Dutch businesses and export in developing countries. Introduction This paper reviews Dutch development cooperation policies for the years 1949-2015 with particular attention for private sector development (PSD). Moreover, this appraisal examines a potential role for Dutch development policies in creating an enabling environment for the ‘home’ (Dutch) and ‘host’ (recipient) private sector to generate (productive) employment. Since the end of the Second World War, the Netherlands has been an active supporter of international development aid. -

Rondom De Nacht Van Schmelzer Parlementaire Geschiedenis Van Nederland Na 1945

Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945 Deel 1, Het kabinet-Schermerhorn-Drees 24 juni 1945 – 3 juli 1946 door F.J.F.M. Duynstee en J. Bosmans Deel 2, De periode van het kabinet-Beel 3 juli 1946 – 7 augustus 1948 door M.D. Bogaarts Deel 3, Het kabinet-Drees-Van Schaik 7 augustus 1948 – 15 maart 1951 onder redactie van P.F. Maas en J.M.M.J. Clerx Deel 4, Het kabinet-Drees II 1951 – 1952 onder redactie van J.J.M. Ramakers Deel 5, Het kabinet-Drees III 1952 – 1956 onder redactie van Carla van Baalen en Jan Ramakers Deel 6, Het kabinet-Drees IV en het kabinet-Beel II 1956 – 1959 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Peter van der Heiden Deel 7,Hetkabinet-DeQuay 1959 – 1963 onder redactie van Jan Willem Brouwer en Jan Ramakers Deel 8, De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963 – 1967 onder redactie van Peter van der Heiden en Alexander van Kessel Stichting Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Den Haag Stichting Katholieke Universiteit, Nijmegen Parlementaire geschiedenis van Nederland na 1945, Deel 8 Rondom de Nacht van Schmelzer De kabinetten-Marijnen, -Cals en -Zijlstra 1963-1967 PETER VAN DER HEIDEN EN ALEXANDER VAN KESSEL (RED.) Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis Auteurs: Anne Bos Charlotte Brand Jan Willem Brouwer Peter van Griensven PetervanderHeiden Alexander van Kessel Marij Leenders Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Hilde Reiding Met medewerking van: Mirjam Adriaanse Miel Jacobs Teun Verberne Jonn van Zuthem Boom – Amsterdam Afbeelding omslag: Cals verlaat de Tweede Kamer na de val van zijn kabinet in de nacht van 13 op 14 oktober 1966.[anp] Omslagontwerp: Mesika Design, Hilversum Zetwerk: Velotekst (B.L. -

Het Hof Van Brussel of Hoe Europa Nederland Overneemt

Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt Arendo Joustra bron Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt. Ooievaar, Amsterdam 2000 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jous008hofv01_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl / Arendo Joustra 5 Voor mijn vader Sj. Joustra (1921-1996) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 6 ‘Het hele recht, het hele idee van een eenwordend Europa, wordt gedragen door een leger mensen dat op zoek is naar een volgende bestemming, die het blijkbaar niet in zichzelf heeft kunnen vinden, of in de liefde. Het leger offert zich moedwillig op aan dit traagkruipende monster zonder zich af te vragen waar het vandaan komt, en nog wezenlijker, of het wel bestaat.’ Oscar van den Boogaard, Fremdkörper (1991) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 9 Inleiding - Aan het hof van Brussel Het verhaal over de Europese Unie begint in Brussel. Want de hoofdstad van België is tevens de zetel van de voornaamste Europese instellingen. Feitelijk is Brussel de ongekroonde hoofdstad van de Europese superstaat. Hier komt de wetgeving vandaan waaraan in de vijftien lidstaten van de Europese Unie niets meer kan worden veranderd. Dat is wennen voor de nationale hoofdsteden en regeringscentra als het Binnenhof in Den Haag. Het spel om de macht speelt zich immers niet langer uitsluitend af in de vertrouwde omgeving van de Ridderzaal. Het is verschoven naar Brussel. Vrijwel ongemerkt hebben diplomaten en Europese functionarissen de macht op het Binnenhof veroverd en besturen zij in alle stilte, ongezien en ongecontroleerd, vanuit Brussel de ‘deelstaat’ Nederland. -

Beyond the 'Trauma of Decolonisation': Dutch Cultural Diplomacy During

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Beyond the ‘Trauma of Decolonisation' Dutch Cultural Diplomacy during the West New Guinea Question (1950–62) Kuitenbrouwer, V. DOI 10.1080/03086534.2016.1175736 Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kuitenbrouwer, V. (2016). Beyond the ‘Trauma of Decolonisation': Dutch Cultural Diplomacy during the West New Guinea Question (1950–62). Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 44(2), 306-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2016.1175736 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

From lesson-learning to accountability? Dutch development aid evaluation in transnational perspective, 1964-1977 ABSTRACT The effectiveness and efficiency of modern development aid has been criticized since its post-war inception. Commentators note the lack of feedback and accountability; the sector does not learn from its past mistakes, and no one takes responsibility in case of clear failures. Evaluation, then, is an instrument that enhances both feedback and accountability. Aid evaluation in one form or another takes place on a massive scale nowadays. How and why did it come into being? This thesis traces the roots of aid evaluation in the Netherlands in the 1960s and 1970s. It shows that, in the context of growing academic knowledge and international consultation, discussions on the purpose and the locus of evaluation led to the establishment of a dual system of aid evaluation at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Civil servants shaped these debates without significant and direct influence of parliament. Paul Schilder (3978478) Supervisor: dr. L. van de Grift Second reader: prof. dr. B.A. de Graaf Research MA Modern History (1500-2000) Utrecht University 30 835 words 15 August 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It would have taken even more time and effort to finish this thesis without the help and presence of a number of people. One of the professors convincing me to dig deeper and think more critically was Oscar Gelderblom. My debt of gratitude to him is incredibly big, not just for inspiring me intellectually but also for keeping faith in my abilities, for hiring me as his research assistant and for not kicking me off the research master’s programme. -

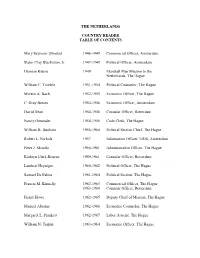

The Netherlands Country Reader Table of Contents

THE NETHERLANDS COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Mary Seymour Olmsted 1946-1949 Commercial Officer, Amsterdam Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 194 -1949 Political Officer, Amsterdam Herman Kleine 1949 Marshall Plan Mission to the Netherlands, The Hague (illiam C. Trimble 1951-1954 Political Counselor, The Hague Morton A. Bach 1952-1955 ,conomic Officer, The Hague C. -ray Bream 1954-1956 ,conomic Officer, Amsterdam .avid .ean 1954-1956 Consular Officer, 0otterdam Nancy Ostrander 1954-1956 Code Clerk, The Hague (illiam B. .unham 1956-1961 Political Section Chief, The Hague 0obert 2. Nichols 195 Information Officer, 4SIS, Amsterdam Peter J. Skoufis 1958-1961 Administrative Officer, The Hague Kathryn Clark-Bourne 1959-1961 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 2ambert Heyniger 1961-1962 Political Officer, The Hague Samuel .e Palma 1961-1964 Political Section, The Hague 6rancis M. Kinnelly 1962-1963 Commercial Officer, The Hague 1963-1964 Consular Officer, 0otterdam 6isher Ho8e 1962-1965 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Manuel Abrams 1962-1966 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Margaret 2. Plunkett 1962-196 2abor Attach:, The Hague (illiam N. Turpin 1963-1964 ,conomic Officer, The Hague .onald 0. Norland 1964-1969 Political Officer, The Hague ,mmerson M. Bro8n 1966-19 1 ,conomic Counselor, The Hague Thomas J. .unnigan 1969-19 2 Political Counselor, The Hague J. (illiam Middendorf, II 1969-19 3 Ambassador, Netherlands ,lden B. ,rickson 19 1-19 4 Consul -eneral, 0otterdam ,ugene M. Braderman 19 1-19 4 Political Officer, Amsterdam 0ay ,. Jones 19 1-19 2 Secretary, The Hague (ayne 2eininger 19 4-19 6 Consular / Administrative Officer, 0otterdam Martin Van Heuven 1932-194 Childhood, 4trecht 19 5-19 8 Political Counselor, The Hague ,lizabeth Ann Bro8n 19 5-19 9 .eputy Chief of Mission, The Hague Victor 2. -

PDF Van Tekst

Memoires 1981-1982 Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, Memoires 1981-1982. Papieren Tijger, [Breda] 2013 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003memo32_01/colofon.php © 2015 dbnl / erven Willem Oltmans 7 Inleiding Voor Willem was seks altijd een soort hobby of een speelding totdat hij de 21-jarige, blonde Nederlander Eduard Voorbach ontmoette. Willems wereld stond in een klap op zijn kop. Helaas bracht deze relatie hem vreugde, noch rust. Willem was 56 en Eduard 21. En geheel volgens zijn karakter probeerde Willem Eduard meteen te bezitten. Daar ging het dan ook fout. Op 24 november 1981 noteert Willem: ‘Het heeft natuurlijk fundamenteel te maken met een diep, diep verlangen om een persoon voor mezelf te hebben, inclusief het complete seksuele beleven. Ga er maar aan staan. Eigenlijk, al ben ik 56 jaar, heb ik me nog nooit echt helemaal, ook seksueel, bij iemand laten gaan, ook niet bij Peter en zelfs niet bij Eduard. Wat ik nu met Eduard beleef is van een vitaal en cruciaal belang, ook met het oog op de jaren die nog komen. Het wordt tijd een vaste relatie aan te gaan. Ik ben klaar om iedereen en alles te laten vallen - behalve Peter en met deze jongen totaal in zee te gaan.’ Willem geeft hier zijn gevoelens duidelijk weer, en helder is hoezeer hij leed aan zijn eenzaamheid, aan zichzelf. In mijn persoonlijk archief uit die tijd vind ik in brieven aan mij hartverscheurende fragmenten, bijvoorbeeld in een brief die hij schreef uit het YMCA in Boston op 7 december: ‘I don't eat, sleep little en am totally miserable. -

How to Balance Open Science with Security Sunday 15 – Wednesday 18 September 2013 | WP1260

Programme Dual-use biology: how to balance open science with security Sunday 15 – Wednesday 18 September 2013 | WP1260 This meeting, which will include government and law enforcement officials, practising scientists, NGOs and academics, will conduct a thoughtful, evidence based appraisal of security concerns surrounding real world examples of past dual-use research of concern as well as hypothetical experiments, and will explore options for managing concerns at all stages, from conception of an experimental question to publication of results. Historical case studies such as H5N1 and mousepox will be used to develop options for coordinated and consensual action, which will then be applied in scenario-building exercises. Questions of outreach to, and engagement with, scientific communities will also be covered. In association with Federal Foreign Office, Berlin; The National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, The Hague; Ministry of Defence, London; National Institutes of Health, Washington DC; Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque Sunday 15 September 1500 Participants arrive 1615-1700 Tea and coffee served 1700-1715 Welcome and introduction Mark Smith Programme Director, Wilton Park, Steyning 1715-1845 1. Introduction to conference: balancing open science and responsible security If the right balance is to be struck, then policy makers and the public must have access to sound, fact-based analysis of potential security concerns and a range of appropriate tools and approaches to manage them. What are the main security concerns, -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

University of Groningen Jelle Zal Wel Zien Harmsma, Jonne

University of Groningen Jelle zal wel zien Harmsma, Jonne DOI: 10.33612/diss.67125602 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Harmsma, J. (2018). Jelle zal wel zien: Jelle Zijlstra, een eigenzinnig leven tussen politiek en economie. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. https://doi.org/10.33612/diss.67125602 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 26-09-2021 Jelle zal wel zien Jelle zal wel zien_150x230_proefschrift.indd 1 31-10-18 17:41 Jelle zal wel zien_150x230_proefschrift.indd 2 31-10-18 17:41 Jelle zal wel zien Jelle Zijlstra, een eigenzinnig leven tussen politiek en economie Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnif cus prof. -

First Worldwide Cybersecurity Summit

FIRST WORLDWIDE CYBERSECURITY SUMMIT Broadening the Dialogue in a Single Location Protecting the Digital Economy Dallas, Texas May 3-5, 2010 Khaled Abdelghany, Assistant Professor, Southern Methodist University Ahmad Sa'ad Abubakar, PSO, International Cooperation, Directorate of Cybersecurity, Office of the National Security Adviser, Three Arms Zone, Abuja, Nigeria Carl Adamse, Security Strategist of the Chief Information Officer, Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, The Netherlands Emina Ajvazoska, EastWest Institute Michael Alagna, Director Homeland Security Strategic Initiatives and Policy, Motorola Juma Aldhaheri, IT Security Manager, Ministry of Interior, United Arab Emirates Greg Alexander, CISO, HP Enterprise Services, US Public Sector Stan Alexander, Assistant Vice President, Technology Services, BNSF Railway Dmitri Alperovitch, Vice President, Threat Research, McAfee Peter Altabef, President, Dell Services Datuk Mohd N. Amin, Chairman, Management Board, International Multilateral Partnership Against Cyber Threats (IMPACT), Malaysia Edward G. Amoroso, Senior Vice President and Chief Security Officer, AT&T Services Inc. Darcy Anderson, Vice President, Perot Systems Jose Araujo, Security Research Department Head, Alcatel-Lucent - Bell-Labs Aurélien Ardillier, Personal Assistant to the Secretary General for National Defence (SGND), France Patrick Arnold, Chief Technical Officer, Trustworthy Computing, Microsoft Corporation Raj Asava, Dell Services JC Asenjo, Global Product Manager, Thales e-Security Leslie-Ann Asmus, Lecturer,