Punjab – Balmiki – Inter-Caste Marriage – BJP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

English Version

_ ~iD(1a Series, Vol. VIIN~_ 5! Tuesd.,. Ma, 29. 1tN Jyaistlla 8, I'll (~) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Seceod SellLoD (NID" Lok S.bba) (~ol. VII CO.'alru No .. 51 to 5S) LOI SABRA SEeR.TAII 'I' NIW DELHI "rlC. I RI. ~.0tJ (~I _ ........ I~ 111 81101..1tM v• .,. ... OIatGDI'L IIDIDI .....1 .. JtrfQJ.UpID De tIJtak "...,.. WILL • _.., AI AU ......,.. MID .,.. ... ,...,...,..,. n ....t CONTENTS [Ninth Series, Vol. VII, Second Session, 199011912 (Saka)J No. 51, Tuesday, May 29. 1990/Jyaistha 8, 1912 (Saka) CoLUMNS Papers laid on the Table 1-9 Messages from Rajya Sabha 9-10 legislative Council Bill 10--50 As passed by Rajya Sabha-Laid leave of Absence from the sittings of the House 50--51 Pettion Re. Closure of Refractory and Ceramic Units of Raniganj No.2 52 Works and Durgapur Works of Burn Standard Co. Ltd. West Bengal-Presented Statement by Minister 52-59 Licensing policy on steel Shri Dinesh Goswami Matters Under Rule 377 59-64 (i) Need to set up an Atomic Power Plant in district Puri of 59-60 Orissa at the place proposed by Site Selection Committee for Eastern Region Shri Gop; Nath Gajapathi (ii) Need to include 'Gaund', 'Manjhi' and 'Panika' tribes of 60 Uttar Pradesh in the tist of Scheduled Tribes Shri Mohanlal Jhikram (ii) CoLUMNS (iii) Need to include the project of extension of metre gauge 61 line upto Agartala, Tripura, in the 8th Plan Shri Sontosh Mohan Dev (iv) Need to instal high power T. V. transmitter at Doordarshan 62 Catre, Saharsa in Bihar Shri Surya Narayan Yadav (v) Need to open a Central Research University In Uttrakhand 62 in Uttar Pradesh Shri M.S. -

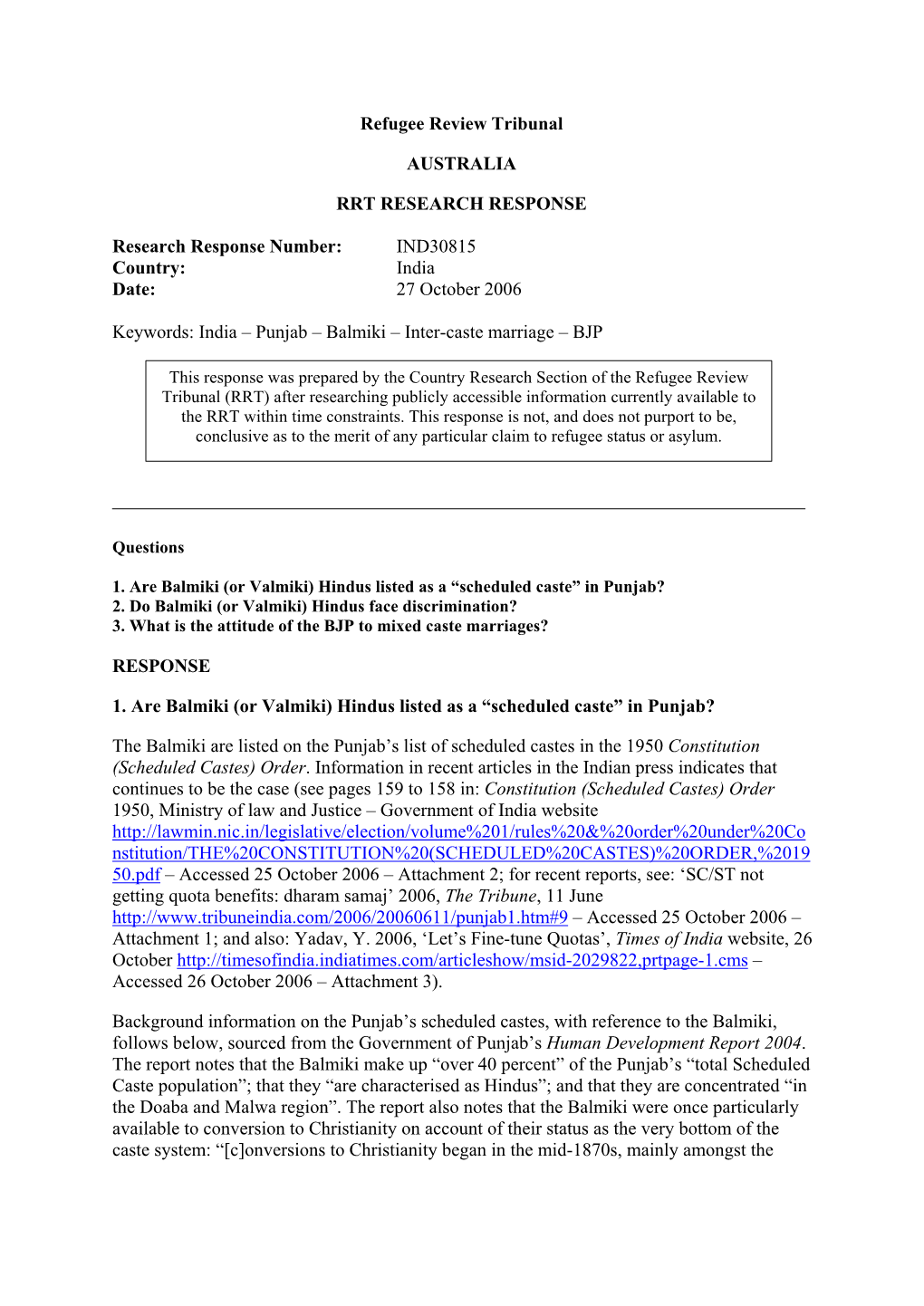

WITHHELD CASES of DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr

Page 1 of 10 fwierYktr is`iKAw BrqI fwierYktoryt pMjwb[ nyVy gurUduAwrw swcw DMn swihb, (mweIkrosw&t ibilifMg) Pyz 3 bI-1, AYs.ey.AYs.ngr (mohwlI) ipMn 160055 imqI 16.03.2020 nUM mwnXog s`kqr skUl is`iKAw pMjwb jI dI pRDwngI hyT giTq kmytI v`loN 873 fI.pI.eI.mwstr/imstRYs kwfr Aqy 74 lYkcrwr srIrk is`iKAw dy hyT ilKy aumIdvwrW dy nwm dy swhmxy drswey kQn Anuswr PYslw ilAw igAw hY:- WITHHELD CASES OF DPE 873 POSTS Regist Sr. Category_ Decision By Education ration Name DOB Remarks STATUS No. Name Recruitment Directorate Id CANDIDATE HAS DONE GRADUATION 60610 25-Aug- GRADUATION ON 25.06.2005 1 SAURABH General IMPROVEMENT ELIGIBLE 352 1983 WITH 47.88%, SO CANDIDATE AFTER CUT OFF IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST DATE 1. CANDIDATE HAS 60613 SUBMITTED NOC FROM HIS 1. APPLY IN 2016 433 VIKRAM 23-Mar- DEPARTMENTT REGARDING 2 General 2. NOC NOT ELIGIBLE 40410 JIT GUPTA 1978 DOING BP.ED ATTACHED 679 2. SO THE CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST. PUNJAB CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED 60621 GURPREE 14-Sep- RESIDENCE PUNJAB RESIDENCE 3 SC (R&O) ELIGIBLE 500 T KAUR 1989 CERTIFICATE NOT CERTIFICATE SO CANDIDATE ATTACHED IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST CANDIDATE HAS SUBMITTED ALL DMC'S OF B.A. ALL THE DMC'S AND BA 60625 MALKEET 12-Apr- 4 SC (M&B) AND DEGREE NOT DEGREE ELIGIBLE 504 SINGH 1986 ATTACHED SO CANDIDATE IS ELIGIBLE FOR THE POST 1. CANDIDATE DOES NOT SHOWN ORIGINAL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDATURE OF THE TASHWIN 60615 15-Jun- QUALIFICATION CANDIDATE IS REJECTED AS 5 DER BC REJECTED 125 1978 DURING SCRUTINY CANDIDATE HAS NOT SHOWN SINGH 2. -

![JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5744/judgment-per-ranjit-more-j-575744.webp)

JUDGMENT [Per Ranjit More, J.]

1 Marata(J) final.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ...Petitioner ]..Petitioner. Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. the Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ]..Respondents. WITH CIVIL APPLICATION NO. 6 OF 2019 IN PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION NO. 175 OF 2018 Gawande Sachin Sominath. ] Age 32 years, Occ : Social Activist, ] R/o Plot No. 64, Lane No. 7, Gajanan Nagar ] Garkheda Parisar, Aurangabad. ]..Applicant. IN THE MATTER BETWEEN Dr. Jishri Laxmnarao Patil, ] Member the Indian Constitutionalist ] Council, Age 39 years, Occu : Advocate, ] Having oce at C/o 109/18, ] Esplanade Mansion, M. G. Road, ] Mumbai 400023. ]..Petitioner. patil-sachin. ::: Uploaded on - 08/07/2019 ::: Downloaded on - 15/07/2019 20:18:51 ::: 2 Marata(J) final.doc Versus 1. The Chief Minister ] of State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 2. The Chief Secretary, ] State of Maharashtra, Mantralaya, ] Mumbai – 400 032. ] ] 3. Anandrao S. Kate, ] Address at Shoop no. 12 ] Building no. 26, A, ] Lullbhai Compound, ] mumbai-400043 ] ] 4. Akhil Bhartiya Maratha ] Mahasangh, ] Reg. No. 669/A, ] Though. Dilip B Jagatap ] ts Oce at.5, Navalkar ] Lane Prarthana Samaj ] Girgaon, Mumbai-04 ] ] 5. Vilas A. Sudrik, ] 265, “Shri Ganesh Chalwal, ] Juie Aunty Compound ] Santosh Nagar, Gaorgaon (E) ] Mumbai-64 ] ] 6. Ashok Patil ] A/G/001, Mehdoot Co-op Society, ] Mahada Vasahat Thane, 4000606 ] ] 7. -

ORDER Since a Corona Positive Case Has Been Reported from VRDL

ORDER Since a Corona positive case has been reported from VRDL, Department of Microbiology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Science, Rohtak in Bazigar Mohalla Tohana, Tehsil Tohana District Fatehabad, therefore, the geographical area falling under Bazigar Mohalla from the house of Sh. Baba Ram S/o Sh. Jamal Ram near Jaimal Dairy Bazigar Mohalla to Sh. Vijay S/o Sh. Ramparsad Killa Mohalla Tohana and Bazigar Mohalla from H/o Darbara Saini Halwai and Sultan Bazigar Sant Baba Jandapuri Mandir to H/o Sh. Mahender Singh S/o Sh. Gurmel Singh and H/o Sh. Prithvi S/o Sh. Narata Killa Mohalla Tohana of Tehsil Tohana District Fateahbad is declared as Containment Zone and rest of the area of Bazigar Mohalla, Balmiki Mohalla, Killa Mohalla, Harpal Chowk and Naya Bazar are delclared as Buffer Zone for all the purposes and objective as prescribed in the protocol of nCOVID-19 District Containment Plan (Health Department) to prevent its spread in the adjoining areas. For combating the situation at hand, the following action plan is prescribed to carry out screening of the suspects, testing of all suspected cases, quarantine, isolation, social distancing and other public health measures in the Containment Zone as well as Buffer Zone effectively: 1. 10 Teams comprising of Anganwadi Workers, Asha Workers, MPHW (Male) and ANMs for conducting door to door screening/thermal scanning of each and every person of the entire households falling in the Containment Zone shall be deployed by the Civil Surgeon, Fatehabad and each team would be allocated 25 households. Two Anganwari Supervisors and one WCDPO would be deployed to supervise the work to be carried out by the Asha Workers, Anganwadi workers, MPHW (Male) and ANMs. -

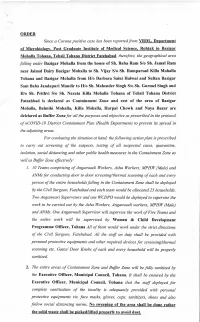

Castes and Subcastes List in Haryana

Castes and Subcastes List in Haryana: State Id State Name Castecode Caste Subcaste 7 HARYANA 7001 ACHARYA PRAJAPATI 7 HARYANA 7002 AHIR YADAV 7 HARYANA 7003 ARORA CHHABRA 7 HARYANA 7004 ARORA CHOPRA 7 HARYANA 7005 ARORA CHUGH 7 HARYANA 7006 ARORA GULATI 7 HARYANA 7007 ARORA KAPOOR 7 HARYANA 7008 ARORA KATHURIYA 7 HARYANA 7009 ARORA KHATRI 7 HARYANA 7010 ARORA MINOCHA 7 HARYANA 7011 ARORA NAGPAL 7 HARYANA 7012 ARORA PANGHA L 7 HARYANA 7013 ARORA RAI 7 HARYANA 7014 ARORA THAKRAL 7 HARYANA 7015 BADAI HARIJAN 7 HARYANA 7016 BADAI JANGADA 7 HARYANA 7017 BADAI 7 HARYANA 7018 BAIRAGI GILL 7 HARYANA 7019 BAIRAGI POWAR 7 HARYANA 7020 BAIRAGI SWAMI 7 HARYANA 7021 BAIRAGI 7 HARYANA 7022 BALMIKI BHANGI 7 HARYANA 7023 BALMIKI 7 HARYANA 7024 BANIYA AGARWAL 7 HARYANA 7025 BANIYA ARORA 7 HARYANA 7026 BANIYA BANSAL 7 HARYANA 7027 BANIYA GARG 7 HARYANA 7028 BANIYA GOYAL 7 HARYANA 7029 BANIYA GUPTA https://www.matchfinder.in/matrimonial/haryana-matrimony This list is provided for free by the courtesy of Matchfinder Matrimony 7 HARYANA 7030 BANIYA JAIN 7 HARYANA 7031 BANIYA JINDAL 7 HARYANA 7032 BANIYA KANSAL 7 HARYANA 7033 BANIYA MAHAJAN 7 HARYANA 7034 BANIYA RANA 7 HARYANA 7035 BANIYA SHAHU 7 HARYANA 7036 BANIYA SINGLA 7 HARYANA 7037 BANIYA 7 HARYANA 7038 BANNSA GARG 7 HARYANA 7039 BAORI 7 HARYANA 7040 BARHAI DHIMAN 7 HARYANA 7041 BARHAI GARG 7 HARYANA 7042 BARHAI KHATI 7 HARYANA 7043 BARHAI SHARMA 7 HARYANA 7044 BARHAI VISHWAKARMA 7 HARYANA 7045 BAWARIA DABLA 7 HARYANA 7046 BAZIGAR BADHAI 7 HARYANA 7047 BHAT ACHARYA 7 HARYANA 7048 BHAT SHARMA 7 HARYANA -

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads

Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity South Asian Nomads - A Literature Review Anita Sharma CREATE PATHWAYS TO ACCESS Research Monograph No. 58 January 2011 University of Sussex Centre for International Education The Consortium for Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) is a Research Programme Consortium supported by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Its purpose is to undertake research designed to improve access to basic education in developing countries. It seeks to achieve this through generating new knowledge and encouraging its application through effective communication and dissemination to national and international development agencies, national governments, education and development professionals, non-government organisations and other interested stakeholders. Access to basic education lies at the heart of development. Lack of educational access, and securely acquired knowledge and skill, is both a part of the definition of poverty, and a means for its diminution. Sustained access to meaningful learning that has value is critical to long term improvements in productivity, the reduction of inter- generational cycles of poverty, demographic transition, preventive health care, the empowerment of women, and reductions in inequality. The CREATE partners CREATE is developing its research collaboratively with partners in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The lead partner of CREATE is the Centre for International Education at the University of Sussex. The partners are: -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

Performance of Scheduled Caste Members of Different Political

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION SUBMISSION OF MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT (FINAL REPORT) IN THE SUBJECT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE PROJECT PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY BY DR. BAL ANANT KAMBLE PRINCIPAL AND HEAD DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE RAYAT SHIKSHAN SANSTHA’S DADA PATIL MAHAVIDYALAYA, KARJAT -414402 DIST – AHMEDNAGAR ( MAHARASHTRA STATE ) Ref. : UGC file No. 5-243/2012(HRP) UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION SUBMISSION OF MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT (FINAL REPORT) IN THE SUBJECT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE PROJECT PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY BY DR. BAL ANANT KAMBLE PRINCIPAL AND HEAD DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE RAYAT SHIKSHAN SANSTHA’S DADA PATIL MAHAVIDYALAYA, KARJAT -414402 DIST – AHMEDNAGAR ( MAHARASHTRA STATE ) MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT Title : PERFORMANCE OF SCHEDULED CASTE MEMBERS OF DIFFERENT POLITICAL PARTIES IN MAHARASHTRA VIDHAN SABHA ELECTED FROM RESERVED CONSTITUENCIES (1962-2009) : AN ANALYTICAL STUDY CONTENTS Chapter No. Contents Page No. i. Introduction I 01 ii. Method of Study and Research Methodology Reserved Constituencies for Scheduled Caste in India and II 07 Delimitation of Constituencies III Scheduled Caste and the Politics of Maharashtra 19 Theoretical Debates About the Scheduled Caste MLAs IV 47 Performance Politics of Scheduled Castes in the Election of V 64 Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Performance Analysis of Scheduled Castes MLAs of VI 86 Different Political Parties of Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha VII Conclusions 146 References 160 List of Interviewed SC MLAs of Maharashtra Vidhan Annexure –I 165 Sabha. Annexure – II Questionnaire 170 Chapter I I – Introduction II – Method of Study and Research Methodology I – Introduction Chapter I is divided in to two parts: Part A and Part B. -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

(SHRI BALWANT SINGH RAMOOWALIA) : (A) in Pursuance of the SINGH RAMOOWALIA) : (A) Yes, Sir

THE MINISTER OF WELFARE (SHRI BALWANT THE MINISTER OF WELFARE (SHRI BALWANT SINGH RAMOOWALIA) : (a) In pursuance of the SINGH RAMOOWALIA) : (a) Yes, Sir. instructions issued by the Deptt. of Personnel and Training (b) As per the enclosed Statement. and the provisions of Section 33 of the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and (c) As soon as the Commission is recenstituted, the Full Participation) Act, 1995, only handicapped Persons are pending requests for castes/sub-castes/communities shall required to be appointed against the posts identified for be examined for inclusion in the Central List of Backward the same. Classes for each State/UT. (b) 1100 jobs in Group C and D posts in Central (d) Individuals/Associations organisations from the Government Offices and Public Sector Undertakings have State of Kerala approached the Commission for inclusion been identified against which handicapped persons are of muslim community in the Central List of Backward appointed. Classes for that State. However, the Commission arrived at the decision not to include 5 social groups, namely, (c) Ministry of Welfare has been insisting for half- Bohra, Cutch Menen Nayat, Turukkan. Dakhni muslims of yearly report on implementation of reservation orders for the muslim community on the basis of findings of an the employment of the handicapped persons in Group C independent study conducted by Anantha Krishna Lyer, and D posts from the Ministries/Departments and Public International Centre for Anthropoligical Studies, Palghat Sector Undertakings indicating the number of posts and other available sources of information with the reserved for handicapped persons and also number of commission. -

Name of Panch Constituencies Pyt. No. Name of Pyt. Halqa Block-Wise

Block-wise/Panchayat wise /Panch Ward wise including area in respect of Block Baggan District Kathua District Name of the Block Name of Pyt. No. Name of Name of Panch Constituencies Area included in the District No. the Block Pyt. Halqa Panch Constituencies Kathua 1 Baggan P.H 1Baggan Lower P.C I Chungian Chungian P.C II Siaru Siaru P.CIII Badola Badola P.C IV Rodal Rodal, Sather Lower P.C V Sather Sather, Sather Upper P.C VI Badhol Badhol, Upper Thamnal P.C VII Dhakki Dhakki, Dhari P.C VIII Thamnal Thamnal, Lower Thamnal P.C IX Kalgote Dulara, Majru, Kharedi P.H 2Baggan Upper P.C I Baggan "B " Baggan, Chuana, Lohri P.C II Riad Riad, Siyari P.CIII Madela Madela, Tallu P.C IV Dhola Pani Dhola Pani, Chibli P.C V Dhar Dhar P.C VI Baggan "A " Baggan, Rozgar, Balla Moh. Junan Tal Moh. P.C VII Kanta Kanta, Rakhwal Page 1 of 136 District Name of the Block Name of Pyt. No. Name of Name of Panch Constituencies Area included in the District No. the Block Pyt. Halqa Panch Constituencies P.H 3Baggan Upper A P.C I Delew "A " i.Delew, Jajal, Selew P.C II Kandew ii.Kandew, Tassar, Deolian, Chenudian P.CIII Delew "B " v.Delew, Sayer, Khil P.C IV Bhatti Bhatti Makounda, Lalotu Makounda P.C V Faroli iii.Faroli, Chick, Thantu P.C VI Panena vi.Panena, Dhadota P.C VII Katli vii.Katli, Pathwad P.H 4 Dehota P.C I Thigan Thigan P.C II Jakhnu Jakhnu P.CIII Dehota-A Dehota-A P.C IV Dehota-B Dehota-B P.C V Sallan Sallan P.C VI Bakali Bakali P.C VII Band Band, Suseter, Mulbary Page 2 of 136 District Name of the Block Name of Pyt.