The Values of Historic Resources for Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts SPORT SPECTACLE, ATHLETIC ACTIVISM, AND THE RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF MEDIATED SPORT A Dissertation in English by Kyle R. King 2017 Kyle R. King Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 The dissertation of Kyle R. King was reviewed and approved* by the following: Debra Hawhee Director of Graduate Studies, Department of English McCourtney Professor of Civic Deliberation Professor of English and of Communication Arts and Sciences Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Cheryl Glenn Distinguished Professor of English and Women’s Studies Director, Program in Writing and Rhetoric Rosa Eberly Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Associate Professor of English Kirt H. Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Jaime Schultz Associate Professor of Kinesiology * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Sports is widely regarded as a “spectacle,” an attention-grabbing consumerist distraction from more important elements of social life. Yet this definition underestimates the rhetorical potency of spectacle, as a context in which athletes may participate in projects of social transformation and institutional reform. Sport Spectacle, Athletic Activism, and the Rhetorical Analysis of Mediated Sport engages a set of case studies that assess the rhetorical conditions that empower or sideline athletes in projects of social change. The introduction builds a -

Copy of KPCC-KVLA-KUOR Quarterly Report APR-JUN 2013

KPCC / KVLA / KUOR Quarterly Programming Report APR MAY JUN 2013 Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Does execution mean justice for the victims of Aurora? If you’re opposed to the death penalty on principal, does the egregiousness of this crime change your view? How Michael Muskal, would you want to see this trial resolved? Karen 4/1/13 LAW Steinhauser, 14:00 How should PCC students, faculty, and administrators handle these problems? Is it Rocha’s responsibility to maintain a yearly schedule? Will the decision to cancel the winter intersession continue to have serious repercussions? Mark Rocha, 4/1/13 EDU Simon Fraser, 19:00 New York City is set to pass legislation requiring thousands of companies to provide paid sick leave to their employees. Some California cities have passed similar legislation, but many more initiatives here have failed. Why? Jill Cucullu, 4/1/13 SPOR Anthony Orona, 14:00 New York City is set to pass legislation requiring thousands of companies to provide paid sick leave to their employees. Some California cities have passed similar Ken Margolies, legislation, but many more initiatives here have failed. Why? John Kabateck, 4/1/13 HEAL Sharon Terman, 22:00 After a week of saber-rattling, North Korea has stepped up its bellicose rhetoric against South Korea and the United States. This weekend, the country announced that it is in a “state of war” with South Korea, and North Korea’s parliament voted to beef up its nuclear weapons arsenal. 4/1/13 FOR David Kang, 10:00 How has big data transformed the way we approach and evaluate information? What will its impact be in years to come? Can this kind of analysis be dangerous, or have significant drawbacks? Kenneth Cukier joins Larry to speak about the revolution of big 4/1/13 LIT data and how it will affect our lives. -

Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2tk5h9h1 Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 11(2) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Rosner, Scott R. Publication Date 2004 DOI 10.5070/LR8112027059 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation Scott R. Rosner* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 194 II. BUSINESS JUSTIFICATION FOR CONSOLIDATION IN THE SPORTS AGENCY INDUSTRY .............................. 196 III. HISTORY OF CONSOLIDATION IN THE SPORTS AGENCY INDUSTRY ................................................ 200 A. SFX Entertainment................................... 200 B . Octagon .............................................. 203 C . A ssante .............................................. 204 D. InternationalManagement Group (IMG) ............ 206 IV. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST CREATED BY CONSOLIDATION IN SPORTS AGENCY ...................................... 207 A. Agencies and Teams Owned by Same Parent Com- pany: The SFX Story ................................. 207 B. Agencies Representing Multiple Players in the Same L eague ............................................... 210 C. Agencies Representing Multiple Players on the Same Team ................................................. 211 D. Agencies Representing Players and Coaches! Managem ent ........................................ -

Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation

Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation Scott R. Rosner* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 194 II. BUSINESS JUSTIFICATION FOR CONSOLIDATION IN THE SPORTS AGENCY INDUSTRY .............................. 196 III. HISTORY OF CONSOLIDATION IN THE SPORTS AGENCY INDUSTRY ................................................ 200 A. SFX Entertainment................................... 200 B . Octagon .............................................. 203 C . A ssante .............................................. 204 D. InternationalManagement Group (IMG) ............ 206 IV. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST CREATED BY CONSOLIDATION IN SPORTS AGENCY ...................................... 207 A. Agencies and Teams Owned by Same Parent Com- pany: The SFX Story ................................. 207 B. Agencies Representing Multiple Players in the Same L eague ............................................... 210 C. Agencies Representing Multiple Players on the Same Team ................................................. 211 D. Agencies Representing Players and Coaches! Managem ent ......................................... 214 E. Agencies Representing Events and Athletes ........... 216 V. CONFLICT OF INTEREST LAWS IMPLICATED .............. 217 A. Model Rules of ProfessionalResponsibility .......... 218 1. R ule 1.7 ......................................... 218 B. Ethics 2000 and the New Rule 1.7 .................... 225 * Lecturer, Legal Studies Department, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. -

As Viewed Through the Pages of the New York Times in 2010 & 2011

THE KOREAN THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGHWAVE THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2010 & 2011 THE KOREAN WAVE AS As Viewed Through the Pages of The New York Times in 2010 & 2011 THE KOREAN THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGH THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2010 & 2011 THE KOREAN WTHE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGHWAVE THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2010 & 2011 THE KOREAN WAVE AS As Viewed Through the Pages of The New York Times in 2010 & 2011 This booklet is a collection of 43 articles selected by Korean Cultural Service New York from articles on Korean culture by The New York Times in 2010 & 2011. THE KOREAN THE KOREAN WAVE AS VIEWED THROUGHWAVE THE PAGES OF THE NEW YORK TIMES IN 2010 & 2011 THE KOREAN WAVE AS As Viewed Through the Pages of The New York Times in 2010 & 2011 First edition, November 2012 Edited & Published by Korean Cultural Service New York 460 Park Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212 759 9550 Fax: 212 688 8640 Website: http://www.koreanculture.org E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2012 by Korean Cultural Service New York All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recovering, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. From The New York Times 2012 © 2012 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. -

James Brown’S Keyboard Composition by Taking Multiple Photographs His Well-Lighted Path?

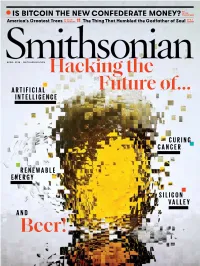

BY CLIVE IS BITCOIN THE NEW CONFEDERATE MONEY? THOMPSON BY ZACH BY RJ America’s Greatest Trees ST. GEORGE The Thing That Humbled the Godfather of Soul SMITH APRIL 2018 • SMITHSONIAN.COM Hacking the ARTIFICIAL Future of... INTELLIGENCE CURING CANCER RENEWABLE ENERGY SILICON VALLEY AND Beer! ADVERTISEMENT Join us for the 2nd annual at March 30 – April 1, 2018 Walter E. Washington Convention Center • Washington, DC Where Science Meets Science Fiction special guests include: Stan Lee, CREATOR, SPIDER-MAN Stephen Amell, Arrow • Dave Bautista, Guardians of the Galaxy • John Boyega, STAR WARS: The Last Jedi Rich DeVaul, Director of Mad Science at X, the moonshot factory • Chris Carberry, CEO, Explore Mars, Inc. Jared Espley, NASA • Terry Hurford, NASA • Erin Macdonald, Dr. Erin Explains the Universe Michael Rooker, Guardians of the Galaxy • Michael Rosenbaum, Smallville • Joan Salute, NASA Tom Welling, Smallville • Cress Williams, Black Lightning • special guest from LOST IN SPACE For more information and to purchase tickets Smithsonian.com/futurecon # futurecon sponsored by Vol. 49 | No. 01 April 2018 features 32 44 Where the Saving Miss Future Is Born Vanessa Fifty years ago, Stanley A new therapy that Kubrick foresaw the uses the body’s own world we live in today immune system to in his pioneering sci-fi fi ght cancer is off ering thriller 2001: A Space hope to patients with Odyssey. Now a new advanced disease generation of innova- by Robin Marantz Henig tors is forging the next revolutions by T. A. Frail 56 Tomorrow Land Silicon Valley’s 34 -

2016–17 Media Guide 6 Championship Drive, Auburn Hills, Mi, 48326 (248) 377-0100 | Fax (248) 377-3260

2016–17 MEDIA GUIDE 6 CHAMPIONSHIP DRIVE, AUBURN HILLS, MI, 48326 (248) 377-0100 | FAX (248) 377-3260 The Detroit Pistons 2016-17 Media Guide was written and edited by Cletus Lewis, Michael Horan and Michelle Fikany. Editorial assistance provided by Kevin Grigg. Design, page layout and production by Mike Jones. Photography by Allen Einstein, David Roberts Photography and NBA Photos. Statistical information provided by Elias Sports Bureau and Chris Thorn. Printing Services by ArborOakland Group. © 2016 Detroit Pistons All NBA and team insignia depicted in this publication are the property of NBA Properties, Inc. and the respective teams and may not be reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior written consent of NBA Properties, Inc. The information contained in this publication was compiled by the Detroit Pistons and is provided as a courtesy to our fans and the media and may be used only for personal or editorial purposes. Any commercial use of this information is prohibited without the prior written consent of the Detroit Pistons. TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA GUIDELINES & INFORMATION Credits............................................1 HISTORY . 119 CREDENTIALS: PRE- AND POST-GAME INTERVIEWS: Table of Contents................................. 2 All-Time Coaching Records . 120-122 Requests for game-by-game credentials should be submitted In accordance with NBA policy, both the Pistons and Media Guidelines & Information . 3 All-Time Roster ..............................123-167 in writing – on company letterhead – to the Pistons’ Public visiting locker rooms will be open to accredited media LEADERSHIP Staff Directory.................................. 4-6 All-Time Numerical Roster .................... 168-171 Relations Department AT LEAST 30 HOURS PRIOR to the members for a 30-minute period prior to each game (6:15 Transactions . -

Analysis of Current Laws and Professional Sports Leagues' Policies Toward Gay Athletes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St. John's University School of Law Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 28 Issue 4 Volume 28, Summer 2016, Issue 4 Article 4 June 2016 Elimination of the Locker Room Closet: Analysis of Current Laws and Professional Sports Leagues' Policies Toward Gay Athletes Sayed Masoud Mortazavi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Recommended Citation Sayed Masoud Mortazavi (2016) "Elimination of the Locker Room Closet: Analysis of Current Laws and Professional Sports Leagues' Policies Toward Gay Athletes," Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development: Vol. 28 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred/vol28/iss4/4 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORTAZAVI MACRO-1 - SMM EDITS (DO NOT DELETE) 6/23/2016 1:19 PM ELIMINATION OF THE LOCKER ROOM CLOSET: ANALYSIS OF CURRENT LAWS AND PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LEAGUES’ POLICIES TOWARD GAY ATHLETES SAYED MASOUD MORTAZAVI1 “When coaches tell you you’re a faggot when you play poorly, you can’t really share who you are with people.”2 INTRODUCTION “I’m gay.”3 On February 9, 2014, Michael Sam, a college football standout who was expected to be a top National Football League (“NFL”) draft-pick in 2014, made this groundbreaking public announcement.4 At 6’2” and 260 pounds, the All-American defensive lineman was a formidable presence on the field during his four years at the University of Missouri.5 Sam was named the top defensive player in the Southeastern Conference,6 which is widely considered to be the best conference in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (“NCAA”). -

2018–19 Media Guide 6 Championship Drive, Auburn Hills, Mi, 48326 (248) 377-0100 | Fax (248) 377-3260

2018–19 MEDIA GUIDE 6 CHAMPIONSHIP DRIVE, AUBURN HILLS, MI, 48326 (248) 377-0100 | FAX (248) 377-3260 The Detroit Pistons 2018-19 Media Guide was written and edited by Cletus Lewis and Josh Schur. Editorial assistance provided by Kevin Grigg. Art direction, page layout and design by Mike Jones. Photography by Chris Schwegler, David Roberts Photography and NBA Photos. Statistical information provided by Elias Sports Bureau and Chris Thorn. Printing services by Graphics East. © 2018 Detroit Pistons All NBA and team insignia depicted in this publication are the property of NBA Properties, Inc. and the respective teams and may not be reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior written consent of NBA Properties, Inc. The information contained in this publication was compiled by the Detroit Pistons and is provided as a courtesy to our fans and the media and may be used only for personal or editorial purposes. Any commercial use of this information is prohibited without the prior written consent of the Detroit Pistons. TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA GUIDELINES & INFORMATION Credits............................................1 HISTORY . 131 CREDENTIALS: following the conclusion of each game. Players and coaches Table of Contents................................. 2 All-Time Coaching Records . .132–134 Requests for game-by-game credentials should be submitted are available for interviews at those times, although it is Media Guidelines & Information . 3 All-Time Roster ..............................135–181 in writing – on company letterhead – to the Pistons’ Public recommended that any interview lasting longer than five LEADERSHIP Staff Directory.................................. 4-5 All-Time Numerical Roster ....................182–185 Relations Department AT LEAST 30 HOURS PRIOR to the minutes in duration be arranged in advance through the Transactions . -

NASSS 2016 Abstracts October 28

Thursday, Nov. 3rd NASSS 2016 8 – 9:30 am ABSTRACTS Thursday Sessions Session 1 8:00 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. Session 1A PALMA CEIA 1 Post-Feminism & New Female Subjectivities Organizers: Jessica Francombe-Webb, University of Bath; Kim Toffoletti, Deakin University & Holly Thorpe, University of Waikato Presider: Kim Toffoletti, Deakin University 1A Jennifer McClearen, University of Washington “Branding the Rebellion Against Postfeminist Body Discipline” This paper interrogates the growing cultural discontent with representations of thin and underfed white feminine bodies in postfeminist media culture. More specifically, I examine the trending emphasis in girls and women’s strength, fitness, and athleticism in contemporary brand cultures such as sports organizations and fitness apparel. Sarah Banet-Weiser argued in the 2015 NASSS keynote that the nouveau ‘strong is the new skinny’ advertising mantra is indicative of ‘popular feminism’—a discourse that includes the investment in increasing the self-confidence of girls and women through the consumption of sports and fitness brands. In this paper, I further argue that the contemporary branding of women’s physical culture positions the audience as savvy consumers who can recognize the assumed contradictions between white femininity and physical power. These brands imagine themselves as rebelling against protracted postfeminist notions of white femininity as physically weak and fragile and instead celebrating self-discipline and individual empowerment through the strong female body. However, as image after image of physically attractive white women demonstrate, this brand of empowerment is limited to bodies that maintain hegemonic femininity. The ‘empowered’ white feminine body becomes a vehicle for supporting neoliberalism, ignoring structural and symbolic inequalities, and maintaining white supremacy. -

Hoarding, Hermitage, and the Law: Why We Love the Collyer Brothers

ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY Hoarding, Hermitage, and the Law: Why We Love the Collyer Brothers Kenneth J. Weiss, MD Interest in hoarding behavior has intensified, as it works its way through DSM-V deliberations and treatment models. Meanwhile, both documentarians and fiction writers have embraced accounts of individuals with disposo- phobia and romanticized versions of the Collyer brothers, the Hermits of Harlem. In this article, I examine the range of media and professional attention given to hoarders and their problems and then focus on a potential role for forensic mental health professionals. The psycholegal problems of hoarders include health and zoning code violations that evolve into criminal charges, civil commitment, questions of animal cruelty, landlord-tenant disputes, divorce and custody evaluations, testamentary capacity, and child-neglect charges. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 38:251–7, 2010 As a child in mid-century New York, I heard my interest after Homer’s body was found and a search mother and my friends’ mothers admonish, “Clean for Langley4 revealed that he was buried 10 feet from up your room or you’ll end up like the Collyer broth- where Homer had died.5 Not cleaning one’s room in ers!” Okay, I guessed, I would not want to be like the 1950s, then, was to be headed down the slippery them, whoever they were. As it turned out, the Her- slope toward a Collyeresque outcome. mits of Harlem1 had captured the imaginations of The brothers were sons of an eccentric gynecolo- New Yorkers as iconic hermits and hoarders holed up gist, Herman Collyer, who canoed to work from in a Fifth Avenue home.