Conflicts of Interest and the Shifting Paradigm of Athlete Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Awards National Football Foundation Post-Season & Conference Honors

NATIONAL AWARDS National Football Foundation Coach of the Year Selections wo Stanford coaches have Tbeen named Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association. Clark Shaughnessy, who guid- ed Stanford through a perfect 10- 0 season, including a 21-13 win over Nebraska in the Rose Bowl, received the honor in 1940. Chuck Taylor, who directed Stanford to the Pacific Coast Championship and a meeting with Illinois in the Rose Bowl, was selected in 1951. Jeff Siemon was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2006. Hall of Fame Selections Clark Shaughnessy Chuck Taylor The following 16 players and seven coaches from Stanford University have been selected to the National Football Foundation/College Football Hall of Fame. Post-Season & Conference Honors Player At Stanford Enshrined Heisman Trophy Pacific-10 Conference Honors Ernie Nevers, FB 1923-25 1951 Bobby Grayson, FB 1933-35 1955 Presented to the Most Outstanding Pac-10 Player of the Year Frank Albert, QB 1939-41 1956 Player in Collegiate Football 1977 Guy Benjamin, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill Corbus, G 1931-33 1957 1970 Jim Plunkett, QB Warren Moon, QB, Washington) Bob Reynolds, T 1933-35 1961 Biletnikoff Award 1980 John Elway, QB Bones Hamilton, HB 1933-35 1972 1982 John Elway, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill McColl, E 1949-51 1973 Presented to the Most Outstanding Hugh Gallarneau, FB 1938-41 1982 Receiver in Collegiate Football Tom Ramsey, QB, UCLA 1986 Brad Muster, FB (Offensive Player of the Year) Chuck Taylor, G 1940-42 1984 1999 Troy Walters, -

For Student Success

TRANSFORMING School Environments OUR VISION For Student Success Weaving SKILLS ROPES Relationships 2018 Annual Report Practices to Help All Students Our Vision for Student Success City Year has always been about nurturing and developing young people, from the talented students we serve to our dedicated AmeriCorps members. We put this commitment to work through service in schools across the country. Every day, our AmeriCorps members help students to develop the skills and mindsets needed to thrive in school and in life, while they themselves acquire valuable professional experience that prepares them to be leaders in their careers and communities. We believe that all students can succeed. Supporting the success of our students goes far beyond just making sure they know how to add fractions or write a persuasive essay—students also need to know how to work in teams, how to problem solve and how to work toward a goal. City Year AmeriCorps members model these behaviors and mindsets for students while partnering with teachers and schools to create supportive learning environments where students feel a sense of belonging and agency as they develop the social, emotional and academic skills that will help them succeed in and out of school. When our children succeed, we all benefit. From Our Leadership Table of Contents At City Year, we are committed to partnering Our 2018 Annual Report tells the story of how 2 What We Do 25 Campaign Feature: with teachers, parents, schools and school City Year AmeriCorps members help students 4 How Students Learn Jeannie & Jonathan Lavine districts, and communities to ensure that all build a wide range of academic and social- 26 National Corporate Partners children have access to a quality education that emotional skills to help them succeed in school 6 Alumni Profile: Andrea Encarnacao Martin 28 enables them to reach their potential, develop and beyond. -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

Illegal Procedure

Wendel: Illegal Procedure Published by SURFACE, 1990 1 Syracuse University Magazine, Vol. 6, Iss. 3 [1990], Art. 6 https://surface.syr.edu/sumagazine/vol6/iss3/6 2 Wendel: Illegal Procedure "Payton's perfect for Busch's 'Know When to former Iowa running back Ronnie Harmon (now Say When' campaign," Ki les says, taking a quick with the Buffalo Bills) and Paul Palmer, the 1986 glance at his side mirror and then cutting for day Heisman Trophy runner-up from Temple. light. "He doesn't drink himself and he's already Among those who testified at the Walters-Bloom out there making appearances on the race circuit." trial was Michael Franzese, a captain in the With a B.A. (1975) and law degree (1978) Colombo crime family, who said he invested from Syracuse University, Kiles is one of a half $50,000 in the agents' business and gave Walters dozen SU alumni who are deal-makers in the permission to use his name to enforce contracts world of sports. Kiles, once the agent for Orange wi th players. men football stars Bill Hurley and Art Monk, has Even though some, most notably NCAA a practice with two offices on M Street in Wash executive director Dick Schultz, said the convic ington. He represents several members of the tion sent a clear message to players and agents National Football League Redskins, and works alike, others maintain the court case merely with companies that want to serve as corporate scratched the surface of the sleazy deals cur sponsors for the 1992 Olympics and 1994 soccer From the public's rently going down in sports. -

2016‐17 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals

2016‐17 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals 2015 Flawless Extra Cards not included (unknown print runs, players highlighted in yellow) Add'l Card Counts (Not print runs) for 2015 Extras: Khris Middleton x1, Pau Gasol x1, Kenny Smith x5, Draymond Green x40, Goran Dragic x28, Dennis Schroder x11, Nicolas Batum x14, Marcin Gortat x11, Nikola Vucevic x10, Rudy Gay x10, Tony Parker x10 266 Players with Cards 7 of those players have 6 cards or under, 11 Players only have Diamond Cards (Nash and Dennis Johnson only have 6) Auto Auto TOTAL Auto Diamond Relic Auto Relic Logo Logoman Champ Patch Team Auto Logo‐ Champ Cards Total Only Total Total Patch Patch Man Diamond Tag Diamond Man Tag Aaron Gordon 369 369 112 257 Al Horford 122 122 119 1 2 Al Jefferson 34 34 34 Alex English 57 57 57 Allen Crabbe 98 98 57 41 Allen Iverson 359 309 49 1 229 80 1 Alonzo Mourning 184 178 6 178 Amar'e Stoudemire 41 41 41 Andre Drummond 155 153 2 115 38 2 Andre Iguodala 43 43 41 2 Andre Roberson 1 1 1 Andrei Kirilenko 97 97 97 Andrew Bogut 41 41 41 Andrew Wiggins 311 138 43 130 138 122 2 1 5 Anfernee Hardaway 112 112 112 Anthony Davis 324 274 43 7 212 62 1 1 5 Artis Gilmore 261 232 29 232 29 Austin Rivers 82 82 82 Ben Simmons 43 43 Ben Wallace 186 180 6 174 6 Bernard King 113 113 113 Bill Russell 215 172 43 172 Blake Griffin 290 117 43 130 117 122 2 1 5 Bobby Portis 16 16 16 Bojan Bogdanovic 113 113 56 57 Bradley Beal 43 43 Brandon Ingram 376 255 43 78 60 194 1 74 2 2 Brandon Jennings 41 41 41 Brandon Knight 39 39 39 Brook Lopez 82 82 82 Buddy Hield 413 253 43 117 58 194 1 115 2 C.J. -

{PDF EPUB} Hard Courts by John Feinstein Tennis.Quickfound.Net

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Hard Courts by John Feinstein tennis.quickfound.net. Mary was three days old when the family moved from Brooklyn to Douglaston, Queens. Mary got her first tennis racquet when she was nine--won it in a fishing contest at the Douglaston Pier. She picked the racquet, and old Alex Olmedo model, as her prize because she thought it would be ideal to use for crabbing off the docks. A year later, when she came down with swimmer's ear, she decided to give the prize a try as a tennis racquet, at the Douglaston Club. Once she got through picking the seaweed out of it, she found out she could play pretty well. She began spending hours around the club, looking for people to play with. Most people used the club to swim or to bowl, but there were three clay and two hard tennis courts. She finally found a little runt two years younger than she was who was willing to play with her all day long. His name was John McEnroe. They were both lefties and they both loved Rod Laver. "We played, like, fourteen sets a day, every day," Mary remembers. When Mary was twelve and John was ten, he began to grow a little and catch up to her on the tennis court. One day he beat her 6-0, 6-0, hitting all these weird, wristy touch shots Mary had never seen anyone else hit. After they were done, Mary looked at John and said, "You know something, someday you're going to be the best tennis player in the world." "Shut up," John McEnroe said. -

Newton Wrestling

NEWTON WRESTLING 10 REASONS WHY FOOTBALL PLAYERS SHOULD WRESTLE 1. Agility--The ability of one to change the position of his body efficiently and easily. 2. Quickness--The ability to make a series of movements in a very short period of time. 3. Balance--The maintenance of body equilibrium through muscular control. 4. Flexibility--The ability to make a wide range of muscular movements. 5. Coordination--The ability to put together a combination of movements in a flowing rhythm. 6. Endurance--The development of muscular and cardiovascular-respiratory stamina. 7. Muscular Power (explosiveness)--The ability to use strength and speed simultaneously. 8. Aggressiveness--The willingness to keep on trying or pushing your adversary at all times. 9. Discipline--The desire to make the sacrifices necessary to become a better athlete and person. 10. A Winning Attitude--The inner knowledge that you will do your best - win or lose. NFL FOOTBALL PLAYERS WHO HAVE WRESTLED "I would have all my offensive linemen wrestle if I could." -John Madden - Hall of Fame NFL Coach I'm a huge wrestling fan. Wrestlers have so many great qualities that athletes need to have." - Bob Stoops - Oklahoma Sooners Head Football Coach Ray Lewis*, Baltimore Ravens – 2x FL State Champ - Bo Jackson*, RB, Oakland Raiders - Tedy Bruschi*, ILB, New England Patriots - Willie Roaf*, OT, New Orleans Saints - Warren Sapp*, DT Tampa Bay Buccaneers – FL State Champ Roger Craig*, RB, San Francisco 49’ers - Larry Czonka**, RB, Miami Dolphins - Tony Siragusa*, DT, Baltimore Ravens NJ State Champ - Ricky Williams*, RB, Miami Dolphins -Dahanie Jones, LB, New York Giants - Ronnie Lott**, DB, San Francisco 49’ers - Jim Nance, FB, New England Patriots NCAA Champ - Dan Dierdorff**, OT, St. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE? BJORN NITTMO? Kicker Bjorn Nittmo Chased His NFL Dream for More Than a Decade, Including a Stop in Training Camp with the Buffalo Bills

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE? BJORN NITTMO? Kicker Bjorn Nittmo chased his NFL dream for more than a decade, including a stop in training camp with the Buffalo Bills. He became a recurring character on 'Late Night with David Letterman.' A head injury left Nittmo so shattered that he walked out on his wife and four children. Years later, he continues to drop in, unannounced and unkempt, before taking off again. His estranged family wants him to get help before it's too late. By Tim Graham / News Sports Reporter Illustration by Daniel Zakroczemski / Buffalo News Published Sept. 1, 2016 Bjorn Nittmo is somewhere out there, presumably in the Arizona mountains, maybe installing home-satellite systems but almost certainly running from himself. Eleven years ago he stopped coming home to his wife and four children. The youngest was 6 months old. He had lost part of his memory and still complains about the constant howling in his head from a concussive whomp. He has filed for bankruptcy and faced at least six civil judgments or liens. At some point he began using a different name. There might be a sinister reason to take on an alias, or perhaps he simply grew tired of people asking if he was that Bjorn Nittmo. Yes, he’s the same guy David Letterman introduced in 1989 as “the only Bjorn Nittmo in the New Jersey phonebook.” In actuality he’s the only Bjorn Nittmo in the world, though he is more peculiar than even that. Nittmo was the left-footed, southern-drawled, Swedish placekicker the media treated like a geegaw from a Cracker Barrel store. -

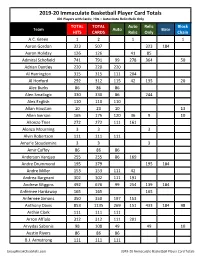

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals 401 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 1 2 1 1 Aaron Gordon 323 507 323 184 Aaron Holiday 126 126 41 85 Admiral Schofield 741 791 99 278 364 50 Adrian Dantley 220 220 220 Al Harrington 315 315 111 204 Al Horford 292 312 115 42 135 20 Alec Burks 86 86 86 Alen Smailagic 330 330 86 244 Alex English 110 110 110 Allan Houston 10 23 10 13 Allen Iverson 165 175 120 36 9 10 Allonzo Trier 272 272 111 161 Alonzo Mourning 3 3 3 Alvin Robertson 111 111 111 Amar'e Stoudemire 3 3 3 Amir Coffey 86 86 86 Anderson Varejao 255 255 86 169 Andre Drummond 195 379 195 184 Andre Miller 153 153 111 42 Andrea Bargnani 302 302 111 191 Andrew Wiggins 492 676 99 254 139 184 Anfernee Hardaway 165 165 165 Anfernee Simons 350 350 197 153 Anthony Davis 853 1135 269 151 433 184 98 Archie Clark 111 111 111 Arron Afflalo 312 312 111 201 Arvydas Sabonis 98 108 49 49 10 Austin Rivers 86 86 86 B.J. Armstrong 111 111 111 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Immaculate Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto Base HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bam Adebayo 163 347 163 184 Baron Davis 98 118 98 20 Ben Simmons 206 390 5 201 184 Bernard King 230 233 230 3 Bill Laimbeer 4 4 4 Bill Russell 104 117 104 13 Bill Walton 35 48 35 13 Blake Griffin 318 502 5 313 184 Bob McAdoo 49 59 49 10 Boban Marjanovic 264 264 111 153 Bogdan Bogdanovic 184 190 141 42 1 6 Bojan Bogdanovic 247 431 247 184 Bol Bol 719 768 99 287 333 -

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues by Robert P.E. Sroka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sport Management) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Judith Grant Long, Chair Professor Sherman Clark Professor Richard Norton Professor Stefan Szymanski Robert P.E. Sroka [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6310-4016 © Robert P.E. Sroka 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, John Sroka and Marie Sroka, as well as George, Lucy, and Ricky. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my parents, John and Marie Sroka, for their love and support. Thank you to my advisor, Judith Grant Long, and my committee members (Sherman Clark, Richard Norton, and Stefan Szymanski) for their guidance, support, and service. This dissertation was funded in part by the Government of Canada through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship, by the Institute for Human Studies PhD Fellowship, and by the Charles Koch Foundation Dissertation Grant. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGURES vii ABSTRACT viii CHAPTER 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature and Theory Review 20 3. Venue TIF Use Inventory 100 4. A Survey and Discussion of TIF Statutes and Major League Venues 181 5. TIF, But-for, and Developer Capture in the Dallas Arena District 234 6. Does the Arena Matter? Comparing Redevelopment Outcomes in 274 Central Dallas TIF Districts 7. Louisville’s KFC Yum! Center, Sales Tax Increment Financing, and 305 Megaproject Underperformance 8. A Hot-N-Ready Disappointment: Little Caesars Arena and 339 The District Detroit 9. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A.