The Combined Effects of SST and the North Atlantic Subtropical High-Pressure System on the Atlantic Basin Tropical Cyclone Interannual Variability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subtropical Storms in the South Atlantic Basin and Their Correlation with Australian East-Coast Cyclones

2B.5 SUBTROPICAL STORMS IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC BASIN AND THEIR CORRELATION WITH AUSTRALIAN EAST-COAST CYCLONES Aviva J. Braun* The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 1. INTRODUCTION With the exception of warmer SST in the Tasman Sea region (0°−60°S, 25°E−170°W), the climate associated with South Atlantic ST In March 2004, a subtropical storm formed off is very similar to that associated with the coast of Brazil leading to the formation of Australian east-coast cyclones (ECC). A Hurricane Catarina. This was the first coastal mountain range lies along the east documented hurricane to ever occur in the coast of each continent: the Great Dividing South Atlantic basin. It is also the storm that Range in Australia (Fig. 1) and the Serra da has made us reconsider why tropical storms Mantiqueira in the Brazilian Highlands (Fig. 2). (TS) have never been observed in this basin The East Australia Current transports warm, although they regularly form in every other tropical water poleward in the Tasman Sea tropical ocean basin. In fact, every other basin predominantly through transient warm eddies in the world regularly sees tropical storms (Holland et al. 1987), providing a zonal except the South Atlantic. So why is the South temperature gradient important to creating a Atlantic so different? The latitudes in which TS baroclinic environment essential for ST would normally form is subject to 850-200 hPa formation. climatological shears that are far too strong for pure tropical storms (Pezza and Simmonds 2. METHODOLOGY 2006). However, subtropical storms (ST), as defined by Guishard (2006), can form in such a. -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons

Meteorology Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects 2018 The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses Part of the Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Messier, Hannah, "The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons" (2018). Meteorology Senior Theses. 40. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses/40 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Meteorology Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Alex Gonzalez — Mentor Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames Iowa Joshua J. Alland — Mentor Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York ABSTRACT The summertime behavior of the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH), African Easterly Jet (AEJ), and the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) can provide clues about key physical aspects of a particular hurricane season. More accurate tropical weather forecasts are imperative to those living in coastal areas around the United States to prevent loss of life and property. -

Lecture 15 Hurricane Structure

MET 200 Lecture 15 Hurricanes Last Lecture: Atmospheric Optics Structure and Climatology The amazing variety of optical phenomena observed in the atmosphere can be explained by four physical mechanisms. • What is the structure or anatomy of a hurricane? • How to build a hurricane? - hurricane energy • Hurricane climatology - when and where Hurricane Katrina • Scattering • Reflection • Refraction • Diffraction 1 2 Colorado Flood Damage Hurricanes: Useful Websites http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/ http://www.nrlmry.navy.mil/tc_pages/tc_home.html http://tropic.ssec.wisc.edu http://www.nhc.noaa.gov Hurricane Alberto Hurricanes are much broader than they are tall. 3 4 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 5 6 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 7 8 Hurricane Raymond: wind shear Typhoon Francisco 9 10 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 11 12 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 13 14 Typhoon Lekima Typhoon Lekima 15 16 Typhoon Lekima Hurricane Priscilla 17 18 Hurricane Priscilla Hurricanes are Tropical Cyclones Hurricanes are a member of a family of cyclones called Tropical Cyclones. West of the dateline these storms are called Typhoons. In India and Australia they are called simply Cyclones. 19 20 Hurricane Isaac: August 2012 Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones • Low pressure systems that don’t have fronts • Cyclonic winds (counter clockwise in Northern Hemisphere) • Anticyclonic outflow (clockwise in NH) at upper levels • Warm at their center or core • Wind speeds decrease with height • Symmetric structure about clear "eye" • Latent heat from condensation in clouds primary energy source • Form over warm tropical and subtropical oceans NASA VIIRS Day-Night Band 21 22 • Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: – energy source (latent heat vs temperature gradients) - Winter storms have cold and warm fronts (asymmetric). -

HS Science Distance Learning Activities

HS Science (Earth Science/Physics) Distance Learning Activities TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Dear families, These learning packets are filled with grade level activities to keep students engaged in learning at home. We are following the learning routines with language of instruction that students would be engaged in within the classroom setting. We have an amazing diverse language community with over 65 different languages represented across our students and families. If you need assistance in understanding the learning activities or instructions, we recommend using these phone and computer apps listed below. Google Translate • Free language translation app for Android and iPhone • Supports text translations in 103 languages and speech translation (or conversation translations) in 32 languages • Capable of doing camera translation in 38 languages and photo/image translations in 50 languages • Performs translations across apps Microsoft Translator • Free language translation app for iPhone and Android • Supports text translations in 64 languages and speech translation in 21 languages • Supports camera and image translation • Allows translation sharing between apps 3027 SOUTH NEW HAVEN AVENUE | TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74114 918.746.6800 | www.tulsaschools.org TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Queridas familias: Estos paquetes de aprendizaje tienen actividades a nivel de grado para mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos con la educación en casa. Estamos siguiendo las rutinas de aprendizaje con las palabras que se utilizan en el salón de clases. Tenemos una increíble -

Extratropical Cyclones and Anticyclones

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Courtesy of Jeff Schmaltz, the MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC/NASA Extratropical Cyclones 10 and Anticyclones CHAPTER OUTLINE INTRODUCTION A TIME AND PLACE OF TRAGEDY A LiFE CYCLE OF GROWTH AND DEATH DAY 1: BIRTH OF AN EXTRATROPICAL CYCLONE ■■ Typical Extratropical Cyclone Paths DaY 2: WiTH THE FI TZ ■■ Portrait of the Cyclone as a Young Adult ■■ Cyclones and Fronts: On the Ground ■■ Cyclones and Fronts: In the Sky ■■ Back with the Fitz: A Fateful Course Correction ■■ Cyclones and Jet Streams 298 9781284027372_CH10_0298.indd 298 8/10/13 5:00 PM © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Introduction 299 DaY 3: THE MaTURE CYCLONE ■■ Bittersweet Badge of Adulthood: The Occlusion Process ■■ Hurricane West Wind ■■ One of the Worst . ■■ “Nosedive” DaY 4 (AND BEYOND): DEATH ■■ The Cyclone ■■ The Fitzgerald ■■ The Sailors THE EXTRATROPICAL ANTICYCLONE HIGH PRESSURE, HiGH HEAT: THE DEADLY EUROPEAN HEAT WaVE OF 2003 PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER ■■ Summary ■■ Key Terms ■■ Review Questions ■■ Observation Activities AFTER COMPLETING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO: • Describe the different life-cycle stages in the Norwegian model of the extratropical cyclone, identifying the stages when the cyclone possesses cold, warm, and occluded fronts and life-threatening conditions • Explain the relationship between a surface cyclone and winds at the jet-stream level and how the two interact to intensify the cyclone • Differentiate between extratropical cyclones and anticyclones in terms of their birthplaces, life cycles, relationships to air masses and jet-stream winds, threats to life and property, and their appearance on satellite images INTRODUCTION What do you see in the diagram to the right: a vase or two faces? This classic psychology experiment exploits our amazing ability to recognize visual patterns. -

ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005

MARCH 2008 ANNUAL SUMMARY 1109 ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005 JOHN L. BEVEN II, LIXION A. AVILA,ERIC S. BLAKE,DANIEL P. BROWN,JAMES L. FRANKLIN, RICHARD D. KNABB,RICHARD J. PASCH,JAMIE R. RHOME, AND STACY R. STEWART Tropical Prediction Center, NOAA/NWS/National Hurricane Center, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 2 November 2006, in final form 30 April 2007) ABSTRACT The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active of record. Twenty-eight storms occurred, includ- ing 27 tropical storms and one subtropical storm. Fifteen of the storms became hurricanes, and seven of these became major hurricanes. Additionally, there were two tropical depressions and one subtropical depression. Numerous records for single-season activity were set, including most storms, most hurricanes, and highest accumulated cyclone energy index. Five hurricanes and two tropical storms made landfall in the United States, including four major hurricanes. Eight other cyclones made landfall elsewhere in the basin, and five systems that did not make landfall nonetheless impacted land areas. The 2005 storms directly caused nearly 1700 deaths. This includes approximately 1500 in the United States from Hurricane Katrina— the deadliest U.S. hurricane since 1928. The storms also caused well over $100 billion in damages in the United States alone, making 2005 the costliest hurricane season of record. 1. Introduction intervals for all tropical and subtropical cyclones with intensities of 34 kt or greater; Bell et al. 2000), the 2005 By almost all standards of measure, the 2005 Atlantic season had a record value of about 256% of the long- hurricane season was the most active of record. -

The Interactions Between a Midlatitude Blocking Anticyclone and Synoptic-Scale Cyclones That Occurred During the Summer Season

502 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 126 NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE The Interactions between a Midlatitude Blocking Anticyclone and Synoptic-Scale Cyclones That Occurred during the Summer Season ANTHONY R. LUPO AND PHILLIP J. SMITH Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana 20 September 1996 and 2 May 1997 ABSTRACT Using the Goddard Laboratory for Atmospheres Goddard Earth Observing System 5-yr analyses and the Zwack±Okossi equation as the diagnostic tool, the horizontal distribution of the dynamic and thermodynamic forcing processes contributing to the maintenance of a Northern Hemisphere midlatitude blocking anticyclone that occurred during the summer season were examined. During the development of this blocking anticyclone, vorticity advection, supported by temperature advection, forced 500-hPa height rises at the block center. Vorticity advection and vorticity tilting were also consistent contributors to height rises during the entire life cycle. Boundary layer friction, vertical advection of vorticity, and ageostrophic vorticity tendencies (during decay) consistently opposed block development. Additionally, an analysis of this blocking event also showed that upstream precursor surface cyclones were not only important in block development but in block maintenance as well. In partitioning the basic data ®elds into their planetary-scale (P) and synoptic-scale (S) components, 500-hPa height tendencies forced by processes on each scale, as well as by interactions (I) between each scale, were also calculated. Over the lifetime of this blocking event, the S and P processes were most prominent in the blocked region. During the formation of this block, the I component was the largest and most consistent contributor to height rises at the center point. -

Hurricane & Tornado Risks in June

June 4, 2021 Hurricane & Tornado Risks in June · Several changes in the weather typically occur in June across the Lower 48. Tropical Development · Atlantic hurricane season officially starts June 1, although it has started early the last seven years, including this year. · On average in the Atlantic Basic, one named storm forms every one to two years in June and a hurricane develops about once every five years. · Early in the season, tropical systems tend to form close to the U.S. and often affect the Southeastern U.S., the western Caribbean and parts of Central America. Rainfall, rather than wind, is usually the biggest concern with June tropical cyclones. Tornado Risks · June is typically an active month for tornadoes. · Tornadoes can happen just about anywhere in the Lower 48 in June, given the widespread warmth and humidity. · Low pressure systems can create the ingredients for severe weather in the Plains and Midwest, in particular. The area at greatest risk of tornadoes in June stretches from central Oklahoma into southwestern Minnesota. · Brief, usually weaker tornadoes often occur near the Gulf Coast during the summer. These are usually caused by sea-breeze thunderstorms and sea breeze collisions closer to the coast. Scattered thunderstorms can also create brief tornadoes across much of the South. · Tropical systems can also bring tornadoes, although they are usually weak and short-lived. · Peak hail activity also occurs in June, according to some studies. The Central and Southern Plains see an increase in hail during the early summer due to the combination of the jet stream, moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and daytime heating. -

A Preliminary Investigation of Derecho-Producing Mcss In

P 3.1 TROPICAL CYCLONE TORNADO RECORDS FOR THE MODERNIZED NWS ERA Roger Edwards1 Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 1. INTRODUCTION and BACKGROUND since 1954 was attributable to the weakest (F0) bin of damage rating (Fig. 1). This is the very class of Tornadoes from tropical cyclones (hereafter TCs) tornado that is most common in TC records, and most pose a specialized forecast challenge at time scales difficult to detect in the damage above that from the ranging from days for outlooks to minutes for concurrent or subsequent passage of similarly warnings (Spratt et al. 1997, Edwards 1998, destructive, ambient TC winds. As such, it is possible Schneider and Sharp 2007, Edwards 2008). The (but not quantifiable) that many TC tornadoes have fundamental conceptual and physical tenets of gone unrecorded even in the modern NWS era, due midlatitude supercell prediction, in an ingredients- to their generally ephemeral nature, logistical based framework (e.g., Doswell 1987, Johns and difficulties of visual confirmation, presence of swaths Doswell 1992), fully apply to TC supercells; however, of sparsely populated near-coastal areas (i.e., systematic differences in the relative magnitudes of marshes, swamps and dense forests), and the moisture, instability, lift and shear in TCs (e.g., presence of damage inducers of potentially equal or McCaul 1991) contribute strongly to that challenge. greater impact within the TC envelope. Further, there is a growing realization that some TC tornadoes are not necessarily supercellular in origin (Edwards et al. 2010, this volume). Several major TC tornado climatologies have been published since the 1960s (e.g., Pearson and Sadowski 1965, Hill et al. -

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

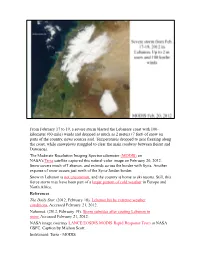

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream. -

Synoptic Meteorology

Lecture Notes on Synoptic Meteorology For Integrated Meteorological Training Course By Dr. Prakash Khare Scientist E India Meteorological Department Meteorological Training Institute Pashan,Pune-8 186 IMTC SYLLABUS OF SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY (FOR DIRECT RECRUITED S.A’S OF IMD) Theory (25 Periods) ❖ Scales of weather systems; Network of Observatories; Surface, upper air; special observations (satellite, radar, aircraft etc.); analysis of fields of meteorological elements on synoptic charts; Vertical time / cross sections and their analysis. ❖ Wind and pressure analysis: Isobars on level surface and contours on constant pressure surface. Isotherms, thickness field; examples of geostrophic, gradient and thermal winds: slope of pressure system, streamline and Isotachs analysis. ❖ Western disturbance and its structure and associated weather, Waves in mid-latitude westerlies. ❖ Thunderstorm and severe local storm, synoptic conditions favourable for thunderstorm, concepts of triggering mechanism, conditional instability; Norwesters, dust storm, hail storm. Squall, tornado, microburst/cloudburst, landslide. ❖ Indian summer monsoon; S.W. Monsoon onset: semi permanent systems, Active and break monsoon, Monsoon depressions: MTC; Offshore troughs/vortices. Influence of extra tropical troughs and typhoons in northwest Pacific; withdrawal of S.W. Monsoon, Northeast monsoon, ❖ Tropical Cyclone: Life cycle, vertical and horizontal structure of TC, Its movement and intensification. Weather associated with TC. Easterly wave and its structure and associated weather. ❖ Jet Streams – WMO definition of Jet stream, different jet streams around the globe, Jet streams and weather ❖ Meso-scale meteorology, sea and land breezes, mountain/valley winds, mountain wave. ❖ Short range weather forecasting (Elementary ideas only); persistence, climatology and steering methods, movement and development of synoptic scale systems; Analogue techniques- prediction of individual weather elements, visibility, surface and upper level winds, convective phenomena.