Tropical Cyclones Over the Mediterranean Sea in Climate Change Simulations M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subtropical Storms in the South Atlantic Basin and Their Correlation with Australian East-Coast Cyclones

2B.5 SUBTROPICAL STORMS IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC BASIN AND THEIR CORRELATION WITH AUSTRALIAN EAST-COAST CYCLONES Aviva J. Braun* The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 1. INTRODUCTION With the exception of warmer SST in the Tasman Sea region (0°−60°S, 25°E−170°W), the climate associated with South Atlantic ST In March 2004, a subtropical storm formed off is very similar to that associated with the coast of Brazil leading to the formation of Australian east-coast cyclones (ECC). A Hurricane Catarina. This was the first coastal mountain range lies along the east documented hurricane to ever occur in the coast of each continent: the Great Dividing South Atlantic basin. It is also the storm that Range in Australia (Fig. 1) and the Serra da has made us reconsider why tropical storms Mantiqueira in the Brazilian Highlands (Fig. 2). (TS) have never been observed in this basin The East Australia Current transports warm, although they regularly form in every other tropical water poleward in the Tasman Sea tropical ocean basin. In fact, every other basin predominantly through transient warm eddies in the world regularly sees tropical storms (Holland et al. 1987), providing a zonal except the South Atlantic. So why is the South temperature gradient important to creating a Atlantic so different? The latitudes in which TS baroclinic environment essential for ST would normally form is subject to 850-200 hPa formation. climatological shears that are far too strong for pure tropical storms (Pezza and Simmonds 2. METHODOLOGY 2006). However, subtropical storms (ST), as defined by Guishard (2006), can form in such a. -

The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons

Meteorology Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects 2018 The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses Part of the Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Messier, Hannah, "The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons" (2018). Meteorology Senior Theses. 40. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses/40 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Meteorology Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Alex Gonzalez — Mentor Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames Iowa Joshua J. Alland — Mentor Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York ABSTRACT The summertime behavior of the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH), African Easterly Jet (AEJ), and the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) can provide clues about key physical aspects of a particular hurricane season. More accurate tropical weather forecasts are imperative to those living in coastal areas around the United States to prevent loss of life and property. -

Lecture 15 Hurricane Structure

MET 200 Lecture 15 Hurricanes Last Lecture: Atmospheric Optics Structure and Climatology The amazing variety of optical phenomena observed in the atmosphere can be explained by four physical mechanisms. • What is the structure or anatomy of a hurricane? • How to build a hurricane? - hurricane energy • Hurricane climatology - when and where Hurricane Katrina • Scattering • Reflection • Refraction • Diffraction 1 2 Colorado Flood Damage Hurricanes: Useful Websites http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/ http://www.nrlmry.navy.mil/tc_pages/tc_home.html http://tropic.ssec.wisc.edu http://www.nhc.noaa.gov Hurricane Alberto Hurricanes are much broader than they are tall. 3 4 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 5 6 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 7 8 Hurricane Raymond: wind shear Typhoon Francisco 9 10 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 11 12 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 13 14 Typhoon Lekima Typhoon Lekima 15 16 Typhoon Lekima Hurricane Priscilla 17 18 Hurricane Priscilla Hurricanes are Tropical Cyclones Hurricanes are a member of a family of cyclones called Tropical Cyclones. West of the dateline these storms are called Typhoons. In India and Australia they are called simply Cyclones. 19 20 Hurricane Isaac: August 2012 Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones • Low pressure systems that don’t have fronts • Cyclonic winds (counter clockwise in Northern Hemisphere) • Anticyclonic outflow (clockwise in NH) at upper levels • Warm at their center or core • Wind speeds decrease with height • Symmetric structure about clear "eye" • Latent heat from condensation in clouds primary energy source • Form over warm tropical and subtropical oceans NASA VIIRS Day-Night Band 21 22 • Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: – energy source (latent heat vs temperature gradients) - Winter storms have cold and warm fronts (asymmetric). -

ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005

MARCH 2008 ANNUAL SUMMARY 1109 ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005 JOHN L. BEVEN II, LIXION A. AVILA,ERIC S. BLAKE,DANIEL P. BROWN,JAMES L. FRANKLIN, RICHARD D. KNABB,RICHARD J. PASCH,JAMIE R. RHOME, AND STACY R. STEWART Tropical Prediction Center, NOAA/NWS/National Hurricane Center, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 2 November 2006, in final form 30 April 2007) ABSTRACT The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active of record. Twenty-eight storms occurred, includ- ing 27 tropical storms and one subtropical storm. Fifteen of the storms became hurricanes, and seven of these became major hurricanes. Additionally, there were two tropical depressions and one subtropical depression. Numerous records for single-season activity were set, including most storms, most hurricanes, and highest accumulated cyclone energy index. Five hurricanes and two tropical storms made landfall in the United States, including four major hurricanes. Eight other cyclones made landfall elsewhere in the basin, and five systems that did not make landfall nonetheless impacted land areas. The 2005 storms directly caused nearly 1700 deaths. This includes approximately 1500 in the United States from Hurricane Katrina— the deadliest U.S. hurricane since 1928. The storms also caused well over $100 billion in damages in the United States alone, making 2005 the costliest hurricane season of record. 1. Introduction intervals for all tropical and subtropical cyclones with intensities of 34 kt or greater; Bell et al. 2000), the 2005 By almost all standards of measure, the 2005 Atlantic season had a record value of about 256% of the long- hurricane season was the most active of record. -

Hurricane & Tornado Risks in June

June 4, 2021 Hurricane & Tornado Risks in June · Several changes in the weather typically occur in June across the Lower 48. Tropical Development · Atlantic hurricane season officially starts June 1, although it has started early the last seven years, including this year. · On average in the Atlantic Basic, one named storm forms every one to two years in June and a hurricane develops about once every five years. · Early in the season, tropical systems tend to form close to the U.S. and often affect the Southeastern U.S., the western Caribbean and parts of Central America. Rainfall, rather than wind, is usually the biggest concern with June tropical cyclones. Tornado Risks · June is typically an active month for tornadoes. · Tornadoes can happen just about anywhere in the Lower 48 in June, given the widespread warmth and humidity. · Low pressure systems can create the ingredients for severe weather in the Plains and Midwest, in particular. The area at greatest risk of tornadoes in June stretches from central Oklahoma into southwestern Minnesota. · Brief, usually weaker tornadoes often occur near the Gulf Coast during the summer. These are usually caused by sea-breeze thunderstorms and sea breeze collisions closer to the coast. Scattered thunderstorms can also create brief tornadoes across much of the South. · Tropical systems can also bring tornadoes, although they are usually weak and short-lived. · Peak hail activity also occurs in June, according to some studies. The Central and Southern Plains see an increase in hail during the early summer due to the combination of the jet stream, moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and daytime heating. -

A Preliminary Investigation of Derecho-Producing Mcss In

P 3.1 TROPICAL CYCLONE TORNADO RECORDS FOR THE MODERNIZED NWS ERA Roger Edwards1 Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 1. INTRODUCTION and BACKGROUND since 1954 was attributable to the weakest (F0) bin of damage rating (Fig. 1). This is the very class of Tornadoes from tropical cyclones (hereafter TCs) tornado that is most common in TC records, and most pose a specialized forecast challenge at time scales difficult to detect in the damage above that from the ranging from days for outlooks to minutes for concurrent or subsequent passage of similarly warnings (Spratt et al. 1997, Edwards 1998, destructive, ambient TC winds. As such, it is possible Schneider and Sharp 2007, Edwards 2008). The (but not quantifiable) that many TC tornadoes have fundamental conceptual and physical tenets of gone unrecorded even in the modern NWS era, due midlatitude supercell prediction, in an ingredients- to their generally ephemeral nature, logistical based framework (e.g., Doswell 1987, Johns and difficulties of visual confirmation, presence of swaths Doswell 1992), fully apply to TC supercells; however, of sparsely populated near-coastal areas (i.e., systematic differences in the relative magnitudes of marshes, swamps and dense forests), and the moisture, instability, lift and shear in TCs (e.g., presence of damage inducers of potentially equal or McCaul 1991) contribute strongly to that challenge. greater impact within the TC envelope. Further, there is a growing realization that some TC tornadoes are not necessarily supercellular in origin (Edwards et al. 2010, this volume). Several major TC tornado climatologies have been published since the 1960s (e.g., Pearson and Sadowski 1965, Hill et al. -

Storms Are Thunderstorms That Produce Tornadoes, Large Hail Or Are Accompanied by High Winds

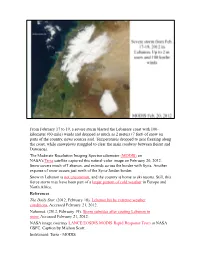

From February 17 to 19, a severe storm blasted the Lebanese coast with 100- kilometer (60-mile) winds and dropped as much as 2 meters (7 feet) of snow on parts of the country, news sources said. Temperatures dropped to near freezing along the coast, while snowplows struggled to clear the main roadway between Beirut and Damascus. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured this natural-color image on February 20, 2012. Snow covers much of Lebanon, and extends across the border with Syria. Another expanse of snow occurs just north of the Syria-Jordan border. Snow in Lebanon is not uncommon, and the country is home to ski resorts. Still, this fierce storm may have been part of a larger pattern of cold weather in Europe and North Africa. References The Daily Star. (2012, February 18). Lebanon hit by extreme weather conditions. Accessed February 21, 2012. Naharnet. (2012, February 19). Storm subsides after coating Lebanon in snow. Accessed February 21, 2012. NASA image courtesy LANCE/EOSDIS MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. Caption by Michon Scott. Instrument: Terra - MODIS Flooding is the most common of all natural hazards. Each year, more deaths are caused by flooding than any other thunderstorm related hazard. We think this is because people tend to underestimate the force and power of water. Six inches of fast-moving water can knock you off your feet. Water 24 inches deep can carry away most automobiles. Nearly half of all flash flood deaths occur in automobiles as they are swept downstream. -

Hurricanes: a Century of Scientific Progress

Hurricanes: A Century of Scientific Progress Kerry Emanuel Program in Atmospheres, Oceans, and Climate Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1. Introduction In the early 20th century, at the same time that the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics were being developed, there was essentially no basic understanding of the physics of hurricanes. The energy cycle that sustains such storms was not known, nor were the factors that controlled their movement. What was known about the structure and behavior of hurricanes was inferred largely from visual observations of clouds and damage patterns, and it was widely believed that the storm circulation extended upward only a few kilometers. By the end of the century, the structure and behavior of hurricanes had been thoroughly quantified, thanks to rapid technological progress that brought about such wonders as aircraft, radar and satellites, and the basic physics of the storms themselves as well as their intricate substructure had come to be well understood. This new understanding, coupled with the invention and rapid development of the computer, made it possible to forecast the motion of hurricanes with such accuracy that, given modern communications and transportation, loss of life from hurricanes has been virtually eliminated in the developed world. This chapter chronicles the extraordinary progress in the scientific understanding of hurricanes through the 20th century. We begin with a brief review of progress through World War II, which marked an important turning point in the science of meteorology, and continue with an account of the rapid progress made in the first two decades after the war. Section 4 discusses the very influential CISK theory that was developed in the 1960s. -

ESCI 107 – the Atmosphere Lesson 16 – Tropical Cyclones Reading

ESCI 107 – The Atmosphere Lesson 16 – Tropical Cyclones Reading: Meteorology Today, Chapter 15 TROPICAL CYCLONES l A tropical cyclone is a large, low-pressure system that forms over the tropical oceans. l Tropical cyclones are classified by sustained wind speed as o Tropical disturbance – wind less than 25 knots o Tropical Depression (TD) – wind 25 to 34 knots o Tropical storm (TS) – wind 35 to 64 knots o Hurricane (or Typhoon) – wind 65 knots or greater l Sustained winds means winds averaged over a 1-minute period (in U.S.). o It is the sustained wind that is used to classify tropical cyclones, not the gusts. l A typhoon and a hurricane are the exact same thing. They just have different names in different parts of the world. Global numbers ¡ About 80 tropical cyclones per year world-wide reach tropical storm strength ¡ About 50 – 55 each year world-wide reach hurricane/typhoon strength Safir-Simpson Intensity Scale (used in U.S.) Category Max Sustained Wind knots mph 1 64 - 82 74 - 95 2 83 - 95 96 - 110 3 96 - 113 111 - 130 4 114 - 134 131 - 155 5 135 + 156 + ¡ A major hurricane is a Category III or higher. FORMATION l The energy that drives hurricanes is the latent heat of condensation from the thunderstorms that comprise the hurricane. l Therefore, hurricanes can only form over very warm water, where there is plenty of evaporation to feed moisture to the thunderstorms. o Water temperatures must be at least 26.5°C (about 80°F). o The upper ‘mixed layer’ of the ocean must also be relatively deep (at least 45 meters) so that the waves do not mix away the warm water at the surface. -

Hurricanes and Tropical Storms Location and Extent of All • Severe Thunderstorms Natural Hazards That Can Affect the Jurisdiction

HAZARD I DENTIFICATION The United States and its communities are vulnerable to a wide array of natural hazards that threaten life and property. These hazards include, in no particular order: • Drought 44 CFR Requirement • Extreme Temperatures Part 201.6(c)(2)(i): The risk • Flood assessment shall include a description of the type, • Hurricanes and Tropical Storms location and extent of all • Severe Thunderstorms natural hazards that can affect the jurisdiction. The plan • Tornadoes shall include information on • Wildfire previous occurrences of hazard events and on the • Winter Storms probability of future hazard • Erosion events. • Earthquakes • Sinkholes • Landslides • Dam/Levee Failure Some of these hazards are interrelated (i.e., hurricanes can cause flooding and tornadoes), and some consist of hazardous elements that are not listed separately (i.e., severe thunderstorms can cause lightning; hurricanes can cause coastal erosion). It should also be noted that some hazards, such as severe winter storms, may impact a large area yet cause little damage, while other hazards, such as a tornado, may impact a small area yet cause extensive damage. This section of the Plan provides a general description for each of the hazards listed above along with their hazardous elements, written from a national perspective. Section 4: Page 2 H AZARD I DENTIFICATION N ORTHERN V IRGINIA R EGIONAL H AZARD M ITIGATION P LAN Drought Drought is a natural climatic condition caused by an extended period of limited rainfall beyond that which occurs naturally in a broad geographic area. High temperatures, high winds, and low humidity can worsen drought conditions, and can make areas more susceptible to wildfire. -

Observed Relationships Between Total Lightning Information and Doppler Radar Data During Two Recent Tropical Cyclone Tornado Events in Florida

OBSERVED RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TOTAL LIGHTNING INFORMATION AND DOPPLER RADAR DATA DURING TWO RECENT TROPICAL CYCLONE TORNADO EVENTS IN FLORIDA Scott M. Spratt, David W. Sharp, and Stephen J. Hodanish NOAA/NWS Melbourne, Florida 1. INTRODUCTION The presence of a unique (total) lightning detection network and a nearby WSR-88D radar within east central Florida has afforded many opportunities to investigate the structure and life cycle of convective cells in great detail. Until now, these studies have focused on two main areas: the apparent relationships between excessive lightning and subsequent severe weather during "warm season" pulse storms (e.g. Hodanish et al., 1998) and the more dynamic storms of the "cool season" (e.g. Williams et al., 1998), and the identification of signatures prior to cloud to ground lightning initiation and cessation (Forbes et al., 1996). This paper will delve into a new topic by providing an initial examination of observed relationships between total lightning signatures and Doppler radar data of tornadic cells within tropical cyclone (TC) outer rainbands. While research of cloud to ground (CG) lightning within tropical cyclones can be considered relatively unexplored (Samsury et al., 1997), examination of the total lightning signal within tropical cyclone rainbands has never been studied, until now. Previous TC CG lightning studies have shown that the amount of discharges to the surface vary considerably from TC to TC, but contain very little CG lightning overall relative to mid latitude mesoscale convective systems (Samsury and Orville, 1994). The literature also agrees that most observed CG lightning occurred within outer convective bands, rather than within inner bands and stratiform precipitation regions. -

Forecast for 2021

EXTENDED RANGE FORECAST OF ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE ACTIVITY AND LANDFALL STRIKE PROBABILITY FOR 2021 We have increased our forecast slightly and continue to forecast an above-average 2021 Atlantic basin hurricane season. Current neutral ENSO conditions are anticipated to persist for the next several months. Sea surface temperatures averaged across most of the tropical Atlantic are now near to slightly above normal, and most of the subtropical North Atlantic remains warmer than normal. Elsa’s development and intensification into a hurricane in the tropical Atlantic also typically portends an active season. We anticipate an above-normal probability for major hurricanes making landfall along the continental United States coastline and in the Caribbean. As is the case with all hurricane seasons, coastal residents are reminded that it only takes one hurricane making landfall to make it an active season for them. They should prepare the same for every season, regardless of how much activity is predicted. (as of 8 July 2021) By Philip J. Klotzbach1, Michael M. Bell2, and Jhordanne Jones3 4 In Memory of William M. Gray This discussion as well as past forecasts and verifications are available online at http://tropical.colostate.edu Jennifer Dimas, Colorado State University media representative, is coordinating media inquiries into this verification. She can be reached at 970-491-1543 or [email protected] Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 Project Sponsors: 1 Research Scientist 2 Associate