Convective Modes for Significant Severe Thunderstorms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast

Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast John T. Snow Regents’ Professor of Meteorology Dean Emeritus, College of Atmospheric and Geographic Sciences, The University of Oklahoma Major contributions from: Dr. Russel Schneider –NOAA Storm Prediction Center Dr. David Stensrud – NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Dr. Ming Xue –Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma Dr. Lou Wicker –NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazards Caucus Alliance Briefing Tornadoes: Understanding how they develop and providing early warning 10:30 am – 11:30 am, Wednesday, 21 July 2010 Senate Capitol Visitors Center 212 Each Year: ~1,500 tornadoes touch down in the United States, causing over 80 deaths, 100s of injuries, and an estimated $1.1 billion in damages Statistics from NOAA Storm Prediction Center Supercell –A long‐lived rotating thunderstorm the primary type of thunderstorm producing strong and violent tornadoes Present Warning System: Warn on Detection • A Warning is the culmination of information developed and distributed over the preceding days sequence of day‐by‐day forecasts identifies an area of high threat •On the day, storm spotters deployed; radars monitor formation, growth of thunderstorms • Appearance of distinct cloud or radar echo features tornado has formed or is about to do so Warning is generated, distributed Present Warning System: Warn on Detection Radar at 2100 CST Radar at 2130 CST with Warning Thunderstorms are monitored using radar A warning is issued based on the detected and -

NEWSLETTER National Weather Association No

NEWSLETTER National Weather Association No. 10 – 12 December 2010 Tracking the Storms the PLOWS Way Adverse road conditions as- sociated with winter storms are re- sponsible for a large portion of the nearly 7000 deaths, 600,000 inju- Inside This Edition ries and 1 4. million accidents that occur in the United States each Internet Based GIS year . Improving cool season quan- Remote Sensing and Storm titative precipitation forecasting Chasing . .2 depends largely on developing a greater understanding of the me- President’s Message . .3 soscale structure and dynamics of cyclonic weather systems . The Pro- This C-130 Hercules Aircraft flies PLOWS missions. New Learning Opportunities filing of Winter Storms (PLOWS) project is aimed at doing just that. During the 2008- from the EJOM . 4. 2009 and 2009-2010 winter seasons, the University of Illinois (UI), the University of Alabama at Huntsville (UAH) and the University of Missouri (UM) placed teams of Scholarship Fundraising . 4. researchers in the field to study winter cyclones across the Midwestern United States NWA on Twitter and Facebook . .5 as part of the PLOWS project . PLOWS was designed to be a comprehensive field campaign, with complementary National Academy of Sciences to numerical modeling studies, that will address outstanding scientific questions targeted Study NWS . .7 at improving our understanding of precipitation substructures in the northwest and warm frontal quadrants of continental extratropical cyclones. The field strategy Professional Development was designed to answer questions about the mesoscale structure of winter storms Opportunities . .7 including: • What are the predominant spatial patterns of organized precipitation NWA Mission and Vision substructures, such as bands and generating cells, in these quadrants and how Statements . -

14B.6 ESTIMATED CONVECTIVE WINDS: RELIABILITY and EFFECTS on SEVERE-STORM CLIMATOLOGY

14B.6 ESTIMATED CONVECTIVE WINDS: RELIABILITY and EFFECTS on SEVERE-STORM CLIMATOLOGY Roger Edwards1 NWS Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK Gregory W. Carbin NWS Weather Prediction Center, College Park, MD 1. BACKGROUND In 2006, NCDC (now NCEI) Storm Data, from By definition, convectively produced surface winds which the SPC database is directly derived, began to ≥50 kt (58 mph, 26m s–1) in the U.S. are classified as record whether gust reports were measured by an severe, whether measured or estimated. Other wind instrument or estimated. Formats before and after reports that can verify warnings and appear in the this change are exemplified in Fig. 1. Storm Data Storm Prediction Center (SPC) severe-weather contains default entries of “Thunderstorm Wind” database (Schaefer and Edwards 1999) include followed by values in parentheses with an acronym assorted forms of convective wind damage to specifying whether a gust was measured (MG) or structures and trees. Though the “wind” portion of the estimated (EG), along with the measured and SPC dataset includes both damage reports and estimated “sustained” convective wind categories (MS specific gust values, this study only encompasses the and ES respectively). MGs from standard ASOS and latter (whether or not damage was documented to AWOS observation sites are available independently accompany any given gust). For clarity, “convective prior to 2006 and have been analyzed in previous gusts” refer to all gusts in the database, regardless of studies [e.g., the Smith et al. (2013) climatology and whether thunder specifically was associated with any mapping]; however specific categorization of EGs and given report. -

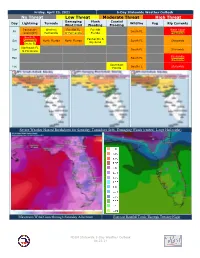

5-Day Weather Outlook 04.23.21

Friday, April 23, 2021 5-Day Statewide Weather Outlook No Threat Low Threat Moderate Threat High Threat Damaging Flash Coastal Day Lightning Tornado Wildfire Fog Rip Currents Wind/Hail Flooding Flooding Panhandle Western Far NW FL Far NW West Coast Fri South FL (overnight) Panhandle W Panhandle Florida Elsewhere North FL Panhandle & Sat Central FL North Florida North Florida South FL Statewide Big Bend South FL Northeast FL Sun South FL Statewide & Peninsula Panhandle Mon South FL Elsewhere Southeast Tue South FL Statewide Florida Severe Weather Hazard Breakdown for Saturday: Tornadoes (left), Damaging Winds (center), Large Hail (right) Maximum Wind Gusts through Saturday Afternoon Forecast Rainfall Totals Through Tuesday Night FDEM Statewide 5-Day Weather Outlook 04.23.21 …Potentially Significant Severe Weather Event for North Florida on Saturday…Two Rounds of Severe Weather Possible Across North Florida…Windy Outside of Storms in North Florida…Hot with Isolated Showers and Storms in the Peninsula this Weekend…Minor Coastal Flooding Possible in Southeast Florida Next Week… Friday - Saturday: A warm front over the Gulf of Mexico tonight will lift northward through the Panhandle and Big Bend Saturday morning. This brings the first round of thunderstorms into the Panhandle late tonight. The Storm Prediction Center has outlined the western Panhandle in a Marginal to Slight Risk of severe weather tonight (level 1-2 of 5). Damaging winds up to 60 mph and isolated tornadoes will be the main threat, mainly after 2 AM CT. On Saturday, the first complex of storms will be rolling across southern Alabama and southern Georgia in the morning and afternoon hours, clipping areas north of I-10 in Florida. -

Polarimetric Radar Characteristics of Tornadogenesis Failure in Supercell Thunderstorms

atmosphere Article Polarimetric Radar Characteristics of Tornadogenesis Failure in Supercell Thunderstorms Matthew Van Den Broeke Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Many nontornadic supercell storms have times when they appear to be moving toward tornadogenesis, including the development of a strong low-level vortex, but never end up producing a tornado. These tornadogenesis failure (TGF) episodes can be a substantial challenge to operational meteorologists. In this study, a sample of 32 pre-tornadic and 36 pre-TGF supercells is examined in the 30 min pre-tornadogenesis or pre-TGF period to explore the feasibility of using polarimetric radar metrics to highlight storms with larger tornadogenesis potential in the near-term. Overall the results indicate few strong distinguishers of pre-tornadic storms. Differential reflectivity (ZDR) arc size and intensity were the most promising metrics examined, with ZDR arc size potentially exhibiting large enough differences between the two storm subsets to be operationally useful. Change in the radar metrics leading up to tornadogenesis or TGF did not exhibit large differences, though most findings were consistent with hypotheses based on prior findings in the literature. Keywords: supercell; nowcasting; tornadogenesis failure; polarimetric radar Citation: Van Den Broeke, M. 1. Introduction Polarimetric Radar Characteristics of Supercell thunderstorms produce most strong tornadoes in North America, moti- Tornadogenesis Failure in Supercell vating study of their radar signatures for the benefit of the operational and research Thunderstorms. Atmosphere 2021, 12, communities. Since the polarimetric upgrade to the national radar network of the United 581. https://doi.org/ States (2011–2013), polarimetric radar signatures of these storms have become well-known, 10.3390/atmos12050581 e.g., [1–5], and many others. -

Subtropical Storms in the South Atlantic Basin and Their Correlation with Australian East-Coast Cyclones

2B.5 SUBTROPICAL STORMS IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC BASIN AND THEIR CORRELATION WITH AUSTRALIAN EAST-COAST CYCLONES Aviva J. Braun* The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 1. INTRODUCTION With the exception of warmer SST in the Tasman Sea region (0°−60°S, 25°E−170°W), the climate associated with South Atlantic ST In March 2004, a subtropical storm formed off is very similar to that associated with the coast of Brazil leading to the formation of Australian east-coast cyclones (ECC). A Hurricane Catarina. This was the first coastal mountain range lies along the east documented hurricane to ever occur in the coast of each continent: the Great Dividing South Atlantic basin. It is also the storm that Range in Australia (Fig. 1) and the Serra da has made us reconsider why tropical storms Mantiqueira in the Brazilian Highlands (Fig. 2). (TS) have never been observed in this basin The East Australia Current transports warm, although they regularly form in every other tropical water poleward in the Tasman Sea tropical ocean basin. In fact, every other basin predominantly through transient warm eddies in the world regularly sees tropical storms (Holland et al. 1987), providing a zonal except the South Atlantic. So why is the South temperature gradient important to creating a Atlantic so different? The latitudes in which TS baroclinic environment essential for ST would normally form is subject to 850-200 hPa formation. climatological shears that are far too strong for pure tropical storms (Pezza and Simmonds 2. METHODOLOGY 2006). However, subtropical storms (ST), as defined by Guishard (2006), can form in such a. -

The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons

Meteorology Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects 2018 The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses Part of the Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Messier, Hannah, "The nflueI nces of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons" (2018). Meteorology Senior Theses. 40. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/mteor_stheses/40 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses and Capstone Projects at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Meteorology Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Influences of the North Atlantic Subtropical High and the African Easterly Jet on Hurricane Tracks During Strong and Weak Seasons Hannah Messier Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa Alex Gonzalez — Mentor Department of Geological and Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University, Ames Iowa Joshua J. Alland — Mentor Department of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University at Albany, State University of New York, Albany, New York ABSTRACT The summertime behavior of the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH), African Easterly Jet (AEJ), and the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) can provide clues about key physical aspects of a particular hurricane season. More accurate tropical weather forecasts are imperative to those living in coastal areas around the United States to prevent loss of life and property. -

Lecture 15 Hurricane Structure

MET 200 Lecture 15 Hurricanes Last Lecture: Atmospheric Optics Structure and Climatology The amazing variety of optical phenomena observed in the atmosphere can be explained by four physical mechanisms. • What is the structure or anatomy of a hurricane? • How to build a hurricane? - hurricane energy • Hurricane climatology - when and where Hurricane Katrina • Scattering • Reflection • Refraction • Diffraction 1 2 Colorado Flood Damage Hurricanes: Useful Websites http://www.wunderground.com/hurricane/ http://www.nrlmry.navy.mil/tc_pages/tc_home.html http://tropic.ssec.wisc.edu http://www.nhc.noaa.gov Hurricane Alberto Hurricanes are much broader than they are tall. 3 4 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 5 6 Hurricane Raymond Hurricane Raymond 7 8 Hurricane Raymond: wind shear Typhoon Francisco 9 10 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 11 12 Typhoon Francisco Typhoon Francisco 13 14 Typhoon Lekima Typhoon Lekima 15 16 Typhoon Lekima Hurricane Priscilla 17 18 Hurricane Priscilla Hurricanes are Tropical Cyclones Hurricanes are a member of a family of cyclones called Tropical Cyclones. West of the dateline these storms are called Typhoons. In India and Australia they are called simply Cyclones. 19 20 Hurricane Isaac: August 2012 Characteristics of Tropical Cyclones • Low pressure systems that don’t have fronts • Cyclonic winds (counter clockwise in Northern Hemisphere) • Anticyclonic outflow (clockwise in NH) at upper levels • Warm at their center or core • Wind speeds decrease with height • Symmetric structure about clear "eye" • Latent heat from condensation in clouds primary energy source • Form over warm tropical and subtropical oceans NASA VIIRS Day-Night Band 21 22 • Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: Differences between hurricanes and midlatitude storms: – energy source (latent heat vs temperature gradients) - Winter storms have cold and warm fronts (asymmetric). -

NWS Storm Prediction Center SPC 24X7 Operations

3/6/2019 NWS Storm Prediction Center FACETs will enable ... • Robust quantification of the weather hazard risk Initial realizations of the FACETs Vision: Real- • Better individual and group decision making • Based on individual needs …through both NWS & the private sector time tools and information for severe weather • Consistent communication and DSS, commensurate to decision making risk • Rigorous quantification of potential impacts Dr. Russell S. Schneider Director, NOAA-NWS Storm Prediction Center 3 March 2019 National Tornado Summit – Public Sheltering Workshop NOAA NWS Storm Prediction Center www.spc.noaa.gov • Forecast tornadoes, thunderstorms, and wildfires nationwide • Forecast information from 8 days to a few minutes in advance • World class team engaged with the research community • Partner with over 120 local National Weather Service offices Current: Forecast & Warning Continuum SPC 24x7 Operations Information Void(s) Outlooks Watches Warnings Event Time Days Hours Minutes Space Regional State Local Uncertainty FACETs: Toward a true continuum optimal for the pace of emergency decision making 1 3/6/2019 Tornado Watch SPC Severe Weather Outlooks Alerting messages issued to the public through media partners SPC Forecaster collaborating on watch characteristics with local NWS offices to communicate the forecast tornado threat to the Public Issued since the early 1950’s SPC Lead Forecaster SPC Lead Forecaster National Experience Average National Experience: 10 years as Lead; almost 20 overall NWS Local Forecast Office Partners -

John Hart Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK

John Hart Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 7th European Conference on Severe Storms, Helsinki, Finland – Friday June 7th, 2013 SPC Overview: US Naonal Weather Service 122 Local Weather Forecast Offices Ususally about 12 meteoroloGists who work rotating shifts. Very busy with daily forecast tasks (public/aviation forecasts, etc). Limited severe weather experience, even if they work in an active office. Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group SPC Overview: US Storm Predic/on Center • Focus on severe storms. • Second set of eyes for the local offices. • Consistent overview of severe storm threat. • HIGH EXPERIENCE LEVELS Forecasts for entire US • Very competitive to join staff (except Alaska and Hawaii) • Stable staff • Few people leave before retirement • No competition with local offices • SPC does not issue warnings • Easy collaboration with local offices Our job is to help the local offices, not compete or overshadow. Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group SPC Overview: US Storm Predic/on Center • Usually four forecasters on shift • Lead Forecaster • 2 mesoscale forecasters • 1 outlook forecaster • Lead Forecaster • Shift supervisor • Makes final call on all products • Issues watches • Promoted from mesoscale/outlook forecaster ranks • Mesoscale Forecaster • Focuses on 0-6 hour forecasts • Writes mesoscale discussions • Outlook Forecaster • Focuses on longer ranges and larger scales • Days 1-8 • Write convective outlooks Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group My Background -

Article Usage of Color Scales on Radar Maps

Bryant, B., M. Holiner, R. Kroot, K. Sherman-Morris, W. B. Smylie, L. Stryjewski, M. Thomas, and C. I. Williams, 2014: Usage of color scales on radar maps. J. Operational Meteor., 2 (14), 169179, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15191/nwajom.2014.0214. Journal of Operational Meteorology Article Usage of Color Scales on Radar Maps BRITTNEY BRYANT, MATTHEW HOLINER, RACHAEL KROOT, KATHLEEN SHERMAN-MORRIS, WILLIAM B. SMYLIE, LISA STRYJEWSKI, MEAGHAN THOMAS, and CHRISTOPHER I. WILLIAMS Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi (Manuscript received 3 October 2013; review completed 14 April 2014) ABSTRACT The visualization of rainfall rates and amounts using colored weather maps has become very common and is crucial for communicating weather information to the public. Little research has been done to investigate which color scales lead to the best understanding of a weather map; however, research has been performed on the general use of color and the theory behind it. Applying color theory specifically to weather maps, we designed this project to see if there was a statistically significant difference in an individual’s interpretation of weather data presented in two different color scales. We used a radar map and a storm-total precipitation map, each presented in both a rainbow scale and a monochromatic green scale, for a total of four images. A survey based on these images was distributed online to students at Mississippi State University. After analyzing the results, we found that people who received the radar image with the green scale were more likely to answer questions associated with that image correctly. However, there was no significant difference in accuracy between the two color scales on the storm-total precipitation map. -

ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005

MARCH 2008 ANNUAL SUMMARY 1109 ANNUAL SUMMARY Atlantic Hurricane Season of 2005 JOHN L. BEVEN II, LIXION A. AVILA,ERIC S. BLAKE,DANIEL P. BROWN,JAMES L. FRANKLIN, RICHARD D. KNABB,RICHARD J. PASCH,JAMIE R. RHOME, AND STACY R. STEWART Tropical Prediction Center, NOAA/NWS/National Hurricane Center, Miami, Florida (Manuscript received 2 November 2006, in final form 30 April 2007) ABSTRACT The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active of record. Twenty-eight storms occurred, includ- ing 27 tropical storms and one subtropical storm. Fifteen of the storms became hurricanes, and seven of these became major hurricanes. Additionally, there were two tropical depressions and one subtropical depression. Numerous records for single-season activity were set, including most storms, most hurricanes, and highest accumulated cyclone energy index. Five hurricanes and two tropical storms made landfall in the United States, including four major hurricanes. Eight other cyclones made landfall elsewhere in the basin, and five systems that did not make landfall nonetheless impacted land areas. The 2005 storms directly caused nearly 1700 deaths. This includes approximately 1500 in the United States from Hurricane Katrina— the deadliest U.S. hurricane since 1928. The storms also caused well over $100 billion in damages in the United States alone, making 2005 the costliest hurricane season of record. 1. Introduction intervals for all tropical and subtropical cyclones with intensities of 34 kt or greater; Bell et al. 2000), the 2005 By almost all standards of measure, the 2005 Atlantic season had a record value of about 256% of the long- hurricane season was the most active of record.