Dayak Students' Attitude Toward Bilingualism in West Kalimantan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

KARLWacana ANDERBECK Vol. 14 No., The 2 Malayic-speaking(October 2012): 265–312Orang Laut 265 The Malayic-speaking Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research KARL ANDERBECK Abstract Southeast Asia is home to many distinct groups of sea nomads, some of which are known collectively as Orang (Suku) Laut. Those located between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula are all Malayic-speaking. Information about their speech is paltry and scattered; while starting points are provided in publications such as Skeat and Blagden (1906), Kähler (1946a, b, 1960), Sopher (1977: 178–180), Kadir et al. (1986), Stokhof (1987), and Collins (1988, 1995), a comprehensive account and description of Malayic Sea Tribe lects has not been provided to date. This study brings together disparate sources, including a bit of original research, to sketch a unified linguistic picture and point the way for further investigation. While much is still unknown, this paper demonstrates relationships within and between individual Sea Tribe varieties and neighbouring canonical Malay lects. It is proposed that Sea Tribe lects can be assigned to four groupings: Kedah, Riau Islands, Duano, and Sekak. Keywords Malay, Malayic, Orang Laut, Suku Laut, Sea Tribes, sea nomads, dialectology, historical linguistics, language vitality, endangerment, Skeat and Blagden, Holle. 1 Introduction Sometime in the tenth century AD, a pair of ships follows the monsoons to the southeast coast of Sumatra. Their desire: to trade for its famed aromatic resins and gold. Threading their way through the numerous straits, the ships’ path is a dangerous one, filled with rocky shoals and lurking raiders. Only one vessel reaches its destination. -

A Stigmatised Dialect

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT Zulfadli Bachelor of Education (Syiah Kuala University, Banda Aceh, Indonesia) Master of Arts in Applied Linguistics (University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia) Thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide December 2014 ii iii iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS A SOCIOLINGUISTIC INVESTIGATION OF ACEHNESE WITH A FOCUS ON WEST ACEHNESE: A STIGMATISED DIALECT i TABLE OF CONTENTS v LIST OF FIGURES xi LIST OF TABLES xv ABSTRACT xvii DECLARATION xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xxi CHAPTER 1 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Preliminary Remarks ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Acehnese society: Socioeconomic and cultural considerations .......................... 1 1.2.1 Acehnese society .................................................................................. 1 1.2.2 Population and socioeconomic life in Aceh ......................................... 6 1.2.3 Workforce and population in Aceh ...................................................... 7 1.2.4 Social stratification in Aceh ............................................................... 13 1.3 History of Aceh settlement ................................................................................ 16 1.4 Outside linguistic influences on the Acehnese ................................................. 19 1.4.1 The Arabic language.......................................................................... -

Language Use and Attitudes Among the Jambi Malays of Sumatra

Language Use and Attitudes Among the Jambi Malays of Sumatra Kristen Leigh Anderbeck SIL International® 2010 SIL e-Books 21 ©2010 SIL International® ISBN: 978-155671-260-9 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL Electronic Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or educational purposes free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Editor-in-Chief George Huttar Volume Editors Grace Tan Rhonda Hartel Jones Compositor Margaret González Acknowledgements A number of people have contributed towards the completion of this study. First of all, I wish to express sincere appreciation for the assistance of Prof. Dr. James T. Collins, my academic supervisor. His guidance, valuable comments, and vast store of reference knowledge were helpful beyond measure. Many thanks also go to several individuals in ATMA (Institute of Malay World and Civilization), particularly Prof. Dato’ Dr. Shamsul Amri Baruddin, Prof. Dr. Nor Hashimah Jalaluddin, and the office staff for their general resourcefulness and support. Additionally, I would like to extend my gratitude to LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Sciences) and Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa (Indonesian Center for Language Development) for sponsoring my fieldwork in Sumatra. To Diana Rozelin, for her eager assistance in obtaining library information and developing the research instruments; and to the other research assistants, Sri Wachyunni, Titin, Sari, Eka, and Erni, who helped in gathering the data, I give my heartfelt appreciation. -

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

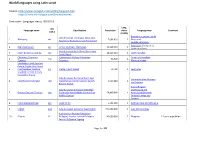

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

Malay Dialects of the Batanghari River Basin (Jambi, Sumatra)

Malay Dialects of the Batanghari River Basin (Jambi, Sumatra) Malay title: DIALEK MELAYU DI LEMBAH SUNGAI BATANGHARI (JAMBI, SUMATRA) Karl Ronald Anderbeck SIL International SIL e-Books 6 ©2008 SIL International Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2007-942663 ISBN-13: 978-155671-189-3 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor Mary Ruth Wise Volume Editors Doris Bartholomew Alanna Boutin Compositor Margaret González ii Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................................................. vi List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. viii List of Maps................................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................... x Abstrak ......................................................................................................................................................... -

On the Perception of Prosodic Prominences and Boundaries in Papuan Malay

Chapter 13 On the perception of prosodic prominences and boundaries in Papuan Malay Sonja Riesberg Universität zu Köln & Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University Janina Kalbertodt Universität zu Köln Stefan Baumann Universität zu Köln Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Universität zu Köln This paper reports the results of two perception experiments on the prosody ofPapuan Malay. We investigated how native Papuan Malay listeners perceive prosodic prominences on the one hand, and boundaries on the other, following the Rapid Prosody Transcription method as sketched in Cole & Shattuck-Hufnagel (2016). Inter-rater agreement between the participants was shown to be much lower for prosodic prominences than for boundaries. Importantly, however, the acoustic cues for prominences and boundaries largely overlap. Hence, one could claim that inasmuch as prominence is perceived at all in Papuan Malay, it is perceived at boundaries, making it doubtful whether prosodic prominence can be usefully distinguished from boundary marking in this language. Our results thus essentially confirm the results found for Standard Indonesian by Goedemans & van Zanten (2007) and vari- ous claims regarding the production of other local varieties of Malay; namely, that Malayic varieties appear to lack stress (i.e. lexical stress as well as post-lexical pitch accents). Sonja Riesberg, Janina Kalbertodt, Stefan Baumann & Nikolaus P. Himmelmann. 2018. On the perception of prosodic prominences and boundaries in Papuan Malay. In Sonja Riesberg, Asako Shiohara & Atsuko Utsumi (eds.), Perspectives on informa- tion structure in Austronesian languages, 389–414. Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1402559 S. Riesberg, J. Kalbertodt, S. Baumann & N. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Gabriella Hermon

CURRICULUM VITAE Gabriella Hermon Department of Linguistics and Cognitive Science 125 East Main Street Newark, DE 19716 Phone: 302-831-1642 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. in Linguistics, Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois, 1981. Dissertation title: Non-Nominative Subject Constructions in the Government and Binding Framework M.A. in Linguistics, Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois, 1977. B.A. in English and American Literature, and General Linguistics, Tel-Aviv University, 1973. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2006- Professor, Department of Linguistics and Cognitive Science, Graduate Director 2005 -2006 Acting Chair, Department of Linguistics, University of Delaware 1992-2005 Associate Professor of Linguistics; Associate Professor of Education, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 1992-2002 Graduate Coordinator of the ESL/Bilingual MA program, School of Education, University of Delaware 1999-2000 Visiting Scientist, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany. 1992-1993 Visiting Fellow, Department of English Language and Literature, National University of Singapore, Singapore. 1988-1992 Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the ESL/Bilingual Specialization, Educational Studies, University of Delaware 1987-1988 Visiting Assistant Professor of Linguistics, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. 1985-1986 Teaching Associate, Department of Linguistics, and Postdoctoral Research Associate, Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 1984-1985 Visiting Associate Professor, Graduate School of Western Languages and Literatures, Tamkang University, Taiwan, ROC. 1982-1984 Teaching Associate, Department of Linguistics, and Postdoctoral Research Associate, Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois. 1981-1982 Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, San Diego State University, San Diego, California. PUBLICATIONS Books, Monographs and Large Databases 2013 A Reference Grammar of Traditional Jambi Malay (Yanti, Peter Cole, Gabriella Hermon and Uri Tadmor), a ca. -

Tamadun of Jambi Melay Region As the Strengthening of National Character Education

TAMADUN OF JAMBI MELAY REGION AS THE STRENGTHENING OF NATIONAL CHARACTER EDUCATION Rustam Faculty of Teacher Training and Education of Jambi University E-mails: [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract.: Malay is a race which inhabits Indonesia or Malay islands in Southeast Asia including Jambi Malay region. Historically, the tamadun of Jambi Malay has been established by Islam and Malay customs have become an important structure of Malay and sovereignty in Jambi. Jambi Malay region that was observed from ethnic grouping, namely social groups that were closely related to Jambi Sultan have twelve groups including Jebus, Pemayung, MaroSebo, Awin, Petajin, Suku Tujuh Koto, Mentong, Panagan, Serdadu, Kebalen, Aur Hitam and central Pinokowan. Jambi Malay area is defined as the area (which practices proper behavior, speaks Malay and they are Muslim). Jambi Malay Community has a character with a philosophy of life, based on: Holding on the Islamic faith as a principle of viewpoint; respecting the leader; greatly guarding traditional customs including prohibited abstinence and customs; giving priority to the elderly; prioritizing family ties and friendship relations; a person who does not return the respect given will be looked down upon; manners; urbane; deliberation/consensus; and work together. Malay society generally has a way of life or custom that is characterized by high civilization values. These characteristics of high civilization are the main foundation for the Jambi Malay community to continue their existence as a society that continues to perpetuate their identity until now. Keywords: Tamadun Of Melay, Jambi Region, National Character Malay race lived in Southeast Asia and around. -

Rescaling Conflictive Access and Property Relations in the Context of REDD+ in Jambi, Indonesia

Rescaling conflictive access and property relations in the context of REDD+ in Jambi, Indonesia Dissertation zur Erlangung des mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades "Doctor rerum naturalium" der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen im Promotionsprogramm Geowissenschaften / Geographie der Georg-August University School of Science (GAUSS) vorgelegt von Dipl. Geogr. Jonas Ibrahim Hein Geboren in Berlin Göttingen 2016 Betreuungsausschuss: Prof. Dr. Heiko Faust Abteilung Humangeographie, Geographisches Institut, Fakultät für Geowissenschaften und Geographie, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Dr. Fariborz Zelli (Associate Professor) Department of Political Science, Environmental Politics Research Group, Lund University (Sweden) Prof. Dr. Christoph Dittrich Abteilung Humangeographie, Geographisches Institut, Fakultät für Geowissenschaften und Geographie, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission Referent: Prof. Dr. Heiko Faust, Abteilung Humangeographie, Geographisches Institut, Fakultät für Geowissenschaften und Geographie, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Korreferent: Dr. Fariborz Zelli (Associate Professor), Department of Political Science, Environmental Politics Research Group, Lund University (Sweden) 2. Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Christoph Dittrich, Abteilung Humangeographie, Geographisches Institut, Fakultät für Geowissenschaften und Geographie, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Weitere Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Michael Flitner, Artec, Forschungszentrum Nachhaltigkeit, Universität -

What Is Riau Indonesian?

What Is Riau Indonesian? David Gil Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig 1 ABSTRACT This paper addresses the question: What is Riau Indonesian? Previous studies of Riau Indonesian have attracted a variety of criticisms suggesting that, in some sense or another, it is not a "real" or "proper" language. This paper takes up and dismisses 12 specific claims regarding the nature of Riau Indonesian, including, among others, that it is a corrupt, broken, imperfect language variety, a language variety without native speakers, an artefact of code switching, or a creole. Examination of Riau Indonesian in sociolinguistic space, in relationship to its substrate and superstrate languages, and in geographical space, in relationship to neighboring varieties of colloquial Indonesian, suggests that there is nothing particularly exceptional about it, and that it is a run-of-the- mill language just like numerous others. In conclusion, it is suggested that other major world languages may also possess a range of language varieties, similar in their broad sociolinguistic profiles to Riau Indonesian, but which in some cases may not yet have been adequately recognized or described. 2 1. IN SEARCH OF A NAME, IN SEARCH OF AN IDENTITY Languages and dialects do not present themselves to us with ready-made names, well- established identities, and their own individual profiles plus three-letter codes in the latest edition of Ethnologue. Often, several distinct languages or dialects share a single name; conversely, a single language or dialect may be known by several different names, or, alternatively, may not have any name of its own. Linguists try to clear up the mess, by engaging in careful descriptions, both of linguistic structure (lexicon, phonology, morphology, syntax, and so forth) and of the sociological and geographical landscape in which such structure is embedded.