The Threatened Plants Database (TPDB) and Its Implications to the BSBI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

Condition of Designated Sites

Scottish Natural Heritage Condition of Designated Sites Contents Chapter Page Summary ii Condition of Designated Sites (Progress to March 2010) Site Condition Monitoring 1 Purpose of SCM 1 Sites covered by SCM 1 How is SCM implemented? 2 Assessment of condition 2 Activities and management measures in place 3 Summary results of the first cycle of SCM 3 Action taken following a finding of unfavourable status in the assessment 3 Natural features in Unfavourable condition – Scottish Government Targets 4 The 2010 Condition Target Achievement 4 Amphibians and Reptiles 6 Birds 10 Freshwater Fauna 18 Invertebrates 24 Mammals 30 Non-vascular Plants 36 Vascular Plants 42 Marine Habitats 48 Coastal 54 Machair 60 Fen, Marsh and Swamp 66 Lowland Grassland 72 Lowland Heath 78 Lowland Raised Bog 82 Standing Waters 86 Rivers and Streams 92 Woodlands 96 Upland Bogs 102 Upland Fen, Marsh and Swamp 106 Upland Grassland 112 Upland Heathland 118 Upland Inland Rock 124 Montane Habitats 128 Earth Science 134 www.snh.gov.uk i Scottish Natural Heritage Summary Background Scotland has a rich and important diversity of biological and geological features. Many of these species populations, habitats or earth science features are nationally and/ or internationally important and there is a series of nature conservation designations at national (Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)), European (Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA)) and international (Ramsar) levels which seek to protect the best examples. There are a total of 1881 designated sites in Scotland, although their boundaries sometimes overlap, which host a total of 5437 designated natural features. -

Notes on Identification Works and Difficult and Under-Recorded Taxa

Notes on identification works and difficult and under-recorded taxa P.A. Stroh, D.A. Pearman, F.J. Rumsey & K.J. Walker Contents Introduction 2 Identification works 3 Recording species, subspecies and hybrids for Atlas 2020 6 Notes on individual taxa 7 List of taxa 7 Widespread but under-recorded hybrids 31 Summary of recent name changes 33 Definition of Aggregates 39 1 Introduction The first edition of this guide (Preston, 1997) was based around the then newly published second edition of Stace (1997). Since then, a third edition (Stace, 2010) has been issued containing numerous taxonomic and nomenclatural changes as well as additions and exclusions to taxa listed in the second edition. Consequently, although the objective of this revised guide hast altered and much of the original text has been retained with only minor amendments, many new taxa have been included and there have been substantial alterations to the references listed. We are grateful to A.O. Chater and C.D. Preston for their comments on an earlier draft of these notes, and to the Biological Records Centre at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology for organising and funding the printing of this booklet. PAS, DAP, FJR, KJW June 2015 Suggested citation: Stroh, P.A., Pearman, D.P., Rumsey, F.J & Walker, K.J. 2015. Notes on identification works and some difficult and under-recorded taxa. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Bristol. Front cover: Euphrasia pseudokerneri © F.J. Rumsey. 2 Identification works The standard flora for the Atlas 2020 project is edition 3 of C.A. Stace's New Flora of the British Isles (Cambridge University Press, 2010), from now on simply referred to in this guide as Stae; all recorders are urged to obtain a copy of this, although we suspect that many will already have a well-thumbed volume. -

Biodiverse Master

Montane, Heath and Bog Habitats MONTANE, HEATH AND BOG HABITATS CONTENTS Montane, heath and bog introduction . 66 Opportunities for action in the Cairngorms . 66 The main montane, heath and bog biodiversity issues . 68 Main threats to UK montane, heath and bog Priority species in the Cairngorms . 72 UK Priority species and Locally important species accounts . 73 Cairngorms montane, heath and bog habitat accounts: • Montane . 84 • Upland heath . 87 • Blanket bog . 97 • Raised bog . 99 ‘Key’ Cairngorms montane, heath and bog species . 100 65 The Cairngorms Local Biodiversity Action Plan MONTANE, HEATH AND BOG INTRODUCTION Around one third of the Cairngorms Partnership area is over 600-650m above sea level (above the natural woodland line, although this is variable from place to place.). This comprises the largest and highest area of montane habitat in Britain, much of which is in a relatively pristine condition. It contains the main summits and plateaux with their associated corries, rocky cliffs, crags, boulder fields, scree slopes and the higher parts of some glens and passes. The vegeta- tion is influenced by factors such as exposure, snow cover and soil type. The main zone is considered to be one of the most spectacular mountain areas in Britain and is recognised nationally and internationally for the quality of its geology, geomorphology and topographic features, and associated soils and biodiversity. c14.5% of the Cairngorms Partnership area (75,000ha) is land above 600m asl. Upland heathland is the most extensive habitat type in the Cairngorms Partnership area, covering c41% of the area, frequently in mosaics with blanket bog. -

List of UK BAP Priority Vascular Plant Species (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Vascular Plant Species (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Vascular Plant Species A list of UK BAP priority vascular plant species, created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report, published in 2007, is provided in the table below. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Scientific name Common Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK name Ireland BAP species? Aceras Man Orchid vascular Y N N N anthropophorum plant Adonis annua Pheasant's- vascular Y U N N eye plant Ajuga chamaepitys Ground-pine vascular Y N N N plant Ajuga pyramidalis Pyramidal vascular Y Y N Y Bugle plant Alchemilla acutiloba a Lady's- vascular Y Y N N mantle plant Alchemilla micans vascular Y Y N N plant Alchemilla minima Alchemilla vascular Y N N N Yes – SAP plant Alchemilla monticola vascular Y N N N plant Alchemilla vascular Y N N N subcrenata plant Alisma gramineum Ribbon- vascular Y N N N Yes – SAP leaved Water- plant plantain Apium repens Creeping vascular Y N N N Yes – SAP Marshwort plant Arabis glabra Tower vascular Y N N N Yes – SAP Mustard plant Arenaria norvegica Arctic vascular N Y N N subsp. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Fall 2013 NARGS

Rock Garden uar terly � Fall 2013 NARGS to ADVERtISE IN thE QuARtERly CoNtACt [email protected] Let me know what yo think A recent issue of a chapter newsletter had an item entitled “News from NARGS”. There were comments on various issues related to the new NARGS website, not all complimentary, and then it turned to the Quarterly online and raised some points about which I would be very pleased to have your views. “The good news is that all the Quarterlies are online and can easily be dowloaded. The older issues are easy to read except for some rather pale type but this may be the result of scanning. There is amazing information in these older issues. The last three years of the Quarterly are also online but you must be a member to read them. These last issues are on Allen Press’s BrightCopy and I find them harder to read than a pdf file. Also the last issue of the Quarterly has 60 extra pages only available online. Personally I find this objectionable as I prefer all my content in a printed bulletin.” This raises two points: Readability of BrightCopy issues versus PDF issues Do you find the BrightCopy issues as good as the PDF issues? Inclusion of extra material in online editions only. Do you object to having extra material in the online edition which can not be included in the printed edition? Please take a moment to email me with your views Malcolm McGregor <[email protected]> CONTRIBUTORS All illustrations are by the authors of articles unless otherwise stated. -

Review of Coverage of the National Vegetation Classification

JNCC Report No. 302 Review of coverage of the National Vegetation Classification JS Rodwell, JC Dring, ABG Averis, MCF Proctor, AJC Malloch, JHJ Schaminée, & TCD Dargie July 2000 This report should be cited as: Rodwell, JS, Dring, JC, Averis, ABG, Proctor, MCF, Malloch, AJC, Schaminée, JNJ, & Dargie TCD, 2000 Review of coverage of the National Vegetation Classification JNCC Report, No. 302 © JNCC, Peterborough 2000 For further information please contact: Habitats Advice Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road, Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ISSN 0963-8091 1 2 Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Coverage of the original NVC project......................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Generation of NVC-related data by the community of users ...................................................................... 5 2 Methodology............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Reviewing the wider European scene......................................................................................................... -

Plant Rank List.Xlsx

FAMILY SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME S RANK Aceraceae Acer ginnala Amur Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer negundo Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. interius Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. negundo Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer negundo var. violaceum Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer pensylvanicum Striped Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer rubrum Red Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer spicatum Mountain Maple S5 Acoraceae Acorus americanus Sweet Flag S5 Acoraceae Acorus calamus Sweet‐flag SNA Adoxaceae Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel S1 Alismataceae Alisma gramineum Narrow‐leaved Water‐plantain S1 Alismataceae Alisma subcordatum Common Water‐plantain SNA Alismataceae Alisma triviale Common Water‐plantain S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria cuneata Arum‐leaved Arrowhead S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria latifolia Broad‐leaved Arrowhead S4S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria rigida Sessile‐fruited Arrowhead S2 Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus Tumble Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus blitoides Prostrate Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus hybridus Smooth Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus retroflexus Redroot Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus spinosus Thorny Amaranth SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus tuberculatus Rough‐fruited water‐hemp SU Anacardiaceae Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac S4 Anacardiaceae Toxicodendron rydbergii Poison‐ivy S5 Apiaceae Aegopodium podagraria Goutweed SNA Apiaceae Anethum graveolens Dill SNA Apiaceae Carum carvi Caraway SNA Apiaceae Cicuta bulbifera Bulb‐bearing Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta maculata Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta virosa Mackenzie's -

Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Post-2020: a Statement of Intent

Scottish Biodiversity Strategy Post-2020: A Statement of Intent December 2020 INTRODUCTION have to change how we interact with and care for nature. The world faces the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. Globally, The twin global crises of biodiversity loss nationally and locally an enormous effort and climate change require us to work is needed to tackle these closely linked with nature to secure a healthier planet. issues. As we move from the United Our Climate Change Plan update outlines Nations Decade on Biodiversity to the new, boosted and accelerated policies, beginning of the United Nations Decade putting us on a pathway to our ambitious of Ecosystem Restoration, with climate change targets and to deliver a preparations being made for the range of co-benefits including for Convention on Biological Diversity’s biodiversity. The way we use land and Conference of the Parties 15 to be held in sea has to simultaneously enable the 2021, this is an appropriate time to reflect transition to net zero as part of a green and set out our broad intentions on how economic recovery, adapt to a changing we will approach the development of a climate and improve the state of nature. new post-2020 Scottish Biodiversity This is an unprecedented tripartite Strategy. challenge. The new UN Decade signals the massive The devastating impact of COVID-19 has effort needed and it is highlighted our need to be far more resilient to pandemics and other ‘shocks’ “…a rallying call for the protection which may arise from degraded nature. and revival of ecosystems around Our Programme for Government and the world, for the benefit of people Climate Change Plan update set out and nature… Only with healthy steps we will take to support a green ecosystems can we enhance recovery. -

NSA Special Qualities

Extract from: Scottish Natural Heritage (2010). The special qualities of the National Scenic Areas . SNH Commissioned Report No.374. The Special Qualities of the North Arran National Scenic Area • A mountain presence that dominates the Firth of Clyde • The contrast between the wild highland interior and the populated coastal strip • The historical landscape in miniature • A dramatic, compact mountain area • A distinctive coastline with a rich variety of forms • One of the most important geological areas in Britain • An exceptional area for outdoor recreation • The experience of highland and island wildlife at close hand Special Quality Further information • A mountain presence that dominates the Firth of Clyde Soaring above the sea, the Arran Arran has been described as ‘the sleeping giant’, its head mountains with their distinctive profile and body comprising the mountains and moors of the island. hold the eye and dominate the Firth of Clyde and its surrounds. Sometimes they The peaks of the NSA can be seen from along the North are clear and distinct, reflected in a Ayrshire coast and from many places inland. It likewise mirror-calm sea, at other times they are dominates the views from the east coast of the Kintyre capped in cloud or wreathed in mist. peninsula, and there are further imposing views from Bute. Gemmell (1998) states that, because the presence of the island is so dominating, the Firth of Clyde cannot be imagined without the presence of Arran and its mountains. • The contrast between the wild highland interior and the populated coastal strip The contrast between the upland and The highland interior of North Arran is comparable with lowland landscapes is striking. -

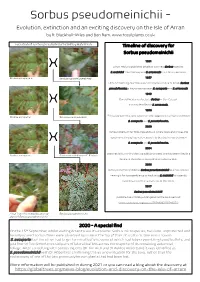

Sorbus Pseudomeinichii - Evolution, Extinction and an Exciting Discovery on the Isle of Arran

Sorbus pseudomeinichii - Evolution, extinction and an exciting discovery on the Isle of Arran by R. Blackhall-Miles and Ben Ram, www.fossilplants.co.uk Evolution of Sorbus pseudomeinichii Ashley Robertson Timeline of discovery for x Sorbus pseudomeinichii 1901 Johan Hedlund publishes details of two new Sorbus species: S. meinichii from Norway and S. arranensis from Arran, Scotland. Sorbus aucuparia L. Sorbus rupicola (Syme) Hedl. 1957 Edmund Warburg describes a second species unique to Arran, Sorbus x pseudofennica; a backcross between S. aucuparia and S. arranensis 1949 Donald McVean collected a Sorbus in Glen Catacol, it is misidentified as S. arranensis. 1996 Phil Lusby saw McVean’s specimen and suggests it is a hybrid between Sorbus aucuparia Sorbus arranensis Hedl. S. aucuparia and S. pseudofennica. x 2000 Ashley Robertson re-finds tree and two others like it and proves the specimens, through genetic research, to be a back cross between S. aucuparia and S. pseudofennica. 2004 Searches fail to re-find the two additional trees; one had been killed in a Sorbus aucuparia Sorbus pseudofennica E. F. Warb flood and the other presumed to be eaten by deer. 2006 Ashley Robertson publishes Sorbus pseudomeinichii as a new species naming it for its resemblance to Hedlund’s S. meinichii it instantly becomes one of the rarest trees in the world. 2017 Sorbus pseudomeinichii published as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (www.iucnredlist.orgspecies/79749367/79749371) A leaf from the newly discovered Sorbus pseudomeinichii plant of Sorbus pseudomeinichii 2020 - A special find On the 15th September, whilst visiting Arran to see it’s endemic Sorbus microspecies, two lone, unprotected and heavily grazed Sorbus trees were observed by us near the top of the Catacol burn.