Thompson in Helmand: Comparing Theory to Practice in British Counter- Insurgency Operations in Afghanistan James Pritcharda; M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

Common Afghans‟, a Useful Construct for Achieving Results in Afghanistan

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 6; June2011 „Common Afghans‟, A useful construct for achieving results in Afghanistan Fahim Youssofzai Associate Professor (Strategic Management) Department of Business Administration, RMC/CMR P.O. Box: 17000, Stn. Forces Kingston, Ontario, K7K 7B4, Canada E-mail: [email protected], Phone: (613) 541 6000 Abstract Considering the seemingly perpetual problems in Afghanistan, this paper defines a new construct – the Common Afghans – and argues why it should be considered in strategic reflections and actions related to stability of this country. It tries to show that part of ill-performance in comes from the fact that the contributions of an important stakeholder “the Common Afghans” are ignored in the processes undertaken by international stakeholders in this country since 2002. It argues why considering the notion “Common Afghans” is helpful for achieving concrete results related to different initiatives undertaken in Afghanistan, by different stakeholders. Key words: Afghanistan, Common Afghans, Accurate unit of analysis, Policies, Strategies 1. Introduction Afghanistan looks to be in perpetual turmoil. In a recent desperate reflection, Robert Blackwill, a former official in the Bush administration and former US ambassador to India suggests partition of Afghanistan since the US cannot win war in this county (POLITICO, 2010). On same mood, Jack Wheeler defines Afghanistan as “...a problem, not a real country…”. According to Wheeler, “…the solution to the problem is not a futile effort of “nation-building” – that effort is doomed to fail – it is nation-building‟s opposite: get rid of the problem by getting rid of the country…” (Wheeler, 2010). -

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs March 1, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30588 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary During 2009, the Obama Administration addressed a deteriorating security environment in Afghanistan. Despite an increase in U.S. forces there during 2006-2008, insurgents were expanding their area and intensity of operations, resulting in higher levels of overall violence. There was substantial Afghan and international disillusionment with corruption in the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, and militants enjoyed a safe haven in parts of Pakistan. Building on assessments completed in the latter days of the Bush Administration, the Obama Administration conducted two “strategy reviews,” the results of which were announced on March 27, 2009, and on December 1, 2009, respectively. Each review included a decision to add combat troops, with the intent of creating the conditions to expand Afghan governance and economic development, rather than on hunting and defeating insurgents in successive operations. The new strategy has been propounded by Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who was appointed top U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan in May 2009. In his August 30, 2009, initial assessment of the situation, Gen. McChrystal recommended a fully resourced, comprehensive counter-insurgency strategy that could require about 40,000 additional forces (beyond 21,000 additional U.S. forces authorized in February 2009). On December 1, 2009, following the second high level policy review, President Obama announced the following: • The provision of 30,000 additional U.S. -

Suicide Attacks in Afghanistan: Why Now?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship Political Science, Department of Spring 5-2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Mujaddidi, Ghulam Farooq, "SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW?" (2013). Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? by Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Political Science Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice C. McMahon Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Patrice C. McMahon Why, contrary to their predecessors, did the Taliban resort to use of suicide attacks in the 2000s in Afghanistan? By drawing from terrorist innovation literature and Michael Horowitz’s adoption capacity theory—a theory of diffusion of military innovation—the author argues that suicide attacks in Afghanistan is better understood as an innovation or emulation of a new technique to retaliate in asymmetric warfare when insurgents face arms embargo, military pressure, and have direct links to external terrorist groups. -

THE VAN DOOS HEAD for AFGHANISTAN Introduction

THE VAN DOOS HEAD FOR AFGHANISTAN Introduction Focus The War Debate Winter of Discontent In the summer of Sergeant Steve Dufour was making his The mission in Afghanistan was a source 2007, Quebec’s way into Molson Stadium in Montreal of debate for much of 2007. The casualty Royal 22nd to see a CFL pre-season game between count of summer 2006, which drove the Regiment— the Alouettes and their arch rivals, the death total to almost 50, left Canadians nicknamed the Van Toronto Argonauts. The game was part feeling numb. So when the pollsters Doos—took over of a publicity campaign designed to started calling shortly after Christmas, it frontline duties in Afghanistan. This drum up public support for the Canadian was no surprise that, at times, the majority News in Review Forces (CF), with 1 700 troops invited of Canadians voiced their opposition to story examines the to the game. With the deployment of the mission in some shape or form. renewed debate the famed Van Doos—the francophone Couple the public opinion issue with a over the Afghan Royal 22nd Regiment—just months series of newspaper articles that suggested mission as the away, efforts were underway to that Canadian forces in Afghanistan deployment of galvanize public support in Quebec were handing prisoners over to Afghan the Van Doos puts the war effort behind the Afghan mission. Dufour, authorities even though they suspected to the top of the a veteran CF soldier who served in that the prisoners were going to be tortured, political agenda Bosnia, was approaching the stadium and it soon became clear that the news in the province of when he noticed the protesters. -

Impeachment Hearing Unprecedented

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's OLUME 41: ISSUE 99 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 7, 2007 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Impeachment hearing unprecedented Jenkins Tonight's ethics case first in Senate history; Morrissey senator questions punishment announces student body vice president Bill By EILEEN DUFFY Andrichik. "In fact, I'm pretty sure it NDForum Assistant News Editor was unanimous." Dworjan's case, however - which will come before the Senate again Immigration will be While Morrissey senator Greg tonight - has required a bit more Dworjan's impeachment is not the first thinking on student government's part. focus offall event decision of its kind for the Student The senator was found guilty of vio Constitution of the Undergraduate Senate, impeachment due to ethical lating two articles in the Constitution of Student Body infractions - such as the two Dworjan the Undergraduate Student Body. First, Alti"'C'LL> xzv JtEMJVALS,.IK'AI.U: A.1irQl •c~ fi«:eoat ~_,_R-.MII By MADDIE HANNA committed - is unprecedented in the he used the LaFortune student govern t. ft.,...__,.'-fbllhl!f~tliJII.IJIIIIIftiR"*"-t8cldf~'M,.._. News Writer group's 38-year history.. ment office's copy machine to make fly l!llfldy~..._._ .. JWIP'Midftlb"('-'ilQo~iltdMI~a-i! ~-a-oer.-. ... ,.._...,..a-li~tllf"-.-'•01'· Last year, when Stanford senator ers urging voters to abstain in the run ~"'-"- ... __...•dft ~~-~-b~'lll-S... David Thaxton went abroad, the off election - but the Constitution pro ••Bil" .......... ~..,.... 1AMfli............. fttt. .............-.)«'lllltlr.NIIIIc~llllll_.. This fall's Notre Dame Senate was forced to officially impeach hibits campaigning anywhere in .....,_.lllfM,_..__........,.....,...,...._.._....,...cw......_,.of.., Forum - the third install and remove him from office in his LaFortune outside of the basement and ~u-t.---fll•~-"'~......,.._ ............ -

Canada in Afghanistan: 2001-2010 a Military Chronology

Canada in Afghanistan: 2001-2010 A Military Chronology Nancy Teeple Royal Military College of Canada DRDC CORA CR 2010-282 December 2010 Defence R&D Canada Centre for Operational Research & Analysis Strategic Analysis Section Canada in Afghanistan: 2001 to 2010 A Military Chronology Prepared By: Nancy Teeple Royal Military College of Canada P.O. Box 17000 Stn Forces Kingston Ontario K7K 7B4 Royal Military College of Canada Contract Project Manager: Mr. Neil Chuka, (613) 998-2332 PWGSC Contract Number: Service-Level Agreement with RMC CSA: Mr. Neil Chuka, Defence Scientist, (613) 998-2332 The scientific or technical validity of this Contract Report is entirely the responsibility of the Contractor and the contents do not necessarily have the approval or endorsement of Defence R&D Canada. Defence R&D Canada – CORA Contract Report DRDC CORA CR 2010-282 December 2010 Principal Author Original signed by Nancy Teeple Nancy Teeple Approved by Original signed by Stephane Lefebvre Stephane Lefebvre Section Head Strategic Analysis Approved for release by Original signed by Paul Comeau Paul Comeau Chief Scientist This work was conducted as part of Applied Research Project 12qr "Influence Activities Capability Assessment". Defence R&D Canada – Centre for Operational Research and Analysis (CORA) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2010 Abstract …….. The following is a chronology of political and military events relating to Canada’s military involvement in Afghanistan between September 2001 and March 2010. -

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs July 20, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30588 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary Upon taking office, the Obama Administration faced a deteriorating security environment in Afghanistan, including an expanding militant presence in some areas, increasing numbers of civilian and military deaths, Afghan and international disillusionment with corruption in the government of Afghan President Hamid Karzai, and the infiltration of Taliban militants from safe havens in Pakistan. The Obama Administration conducted a “strategic review,” the results of which were announced on March 27, 2009, in advance of an April 3-4, 2009, NATO summit. This review built upon assessments completed in the latter days of the Bush Administration, which produced decisions to plan a build-up of U.S. forces in Afghanistan. In part because of the many different causes of instability in Afghanistan, there reportedly were differences within the Obama Administration on a new strategy. The review apparently leaned toward those in the Administration who believe that adding combat troops is less crucial than building governance, although 21,000 U.S. troops are being added during May - September 2009. The new strategy emphasizes non-military steps such as increasing the resources devoted to economic development, building Afghan governance primarily at the local level, reforming the Afghan government, expanding and reforming the Afghan security forces, and trying to improve Pakistan’s efforts to curb militant activity on its soil. -

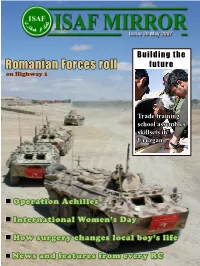

Romanian Forces Roll Future on Highway 1

Building the Romanian Forces roll future on Highway 1 Trade training school assembles skillsets in Uruzgan n Operation Achilles n International Women’s Day n How surgery changes local boy’s life n News and features from every RC In this month’s Mirror May 2007 Romanian armored per- 4 News sonnel carriers enter n Update on Operation Achilles Highway 1 in Zabul. Cover Photo by Catalin Ovreiu n COMISAF Media Roundtable Carpathian 5 NATO & HQ ISAF Hawks secure n News at press time Zabul ........... 6 RC-Captial turn to page 8. n Erdem takes command Celebrating Women’s 7 RC-South Day in Qalat (RC-S) n Achilles spurs development Homeward-bound Royal Marines make last charge 8 Romanian Forces n Feature on security role in Qalat and Kandahar 10 Passing on skills n Trade training gives Afghans knowledge to build future 12 Down south n ISAF troops pass out more than candy to local children n Qalat holds Women’s Day 13 Nursing students n Zabul graduates nursing aids/students Women in Qalat, Zabul province, celebrate International Women’s Day with song March n Canines remain top asset in 8. Photo by Captain Kevin G. Tuttle force protection For more on the festivities ........... turn to page 12. 2 May 2007 ISAF MIRROR Contents 14 ANAP training n ISAF troops provide instruction in Uruzgan The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where n Australian reconstruction team possible, have been kept in their origi- nal form. Opinions expressed are those completes tour of the writers and do not necessarily reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan: a Last Ditch Effort to Turn Around a Failing War

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan: A Last Ditch Effort to Turn Around a Failing War Benjamin P. McCullough Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation McCullough, Benjamin P., "Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan: A Last Ditch Effort to Turn Around a Failing War" (2014). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1423. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1423 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COUNTERINSURGENCY IN AFGHANISTAN: A LAST DITCH EFFORT TO TURN AROUND A FAILING WAR A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By BENJAMIN PATRICK MCCULLOUGH B.A., Wittenberg University, 2009 2014 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL 06/27/2014 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Benjamin Patrick McCullough ENTITLED Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan: A Last Ditch Effort to Turn Around a Failing War BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ______________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. Thesis Director ______________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. Department of Political Science ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. -

Lindsay Cross Resurrection River 1

Lindsay Cross Resurrection River 1 Lindsay Cross Resurrection River 2 INTRODUCTION Praise for the Men of Mercy Series “Lindsay Cross delivers high-powered action, alpha heroes and an exciting conclusion!” - ELLE JAMES New York Times and USA Today bestselling author "This is one of those books that the phrase sit down, shut up and hang on would be used because it’s a wild ride from page one to the end.” - 5 Star Goodreads Review, Redemption River "This book was wall to wall action. Once the danger hit, it never slowed down. I was late leaving my house because there was no way I could stop reading." - 5 Star NetGalley Review, Redemption River Lindsay Cross Resurrection River 3 DOSSIER TASK FORCE SCORPION (TF-S) A branch of Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) Ft. Grenada, MS MACK GREY: Detachment Commander, Captain ♣ Recruited from the 75th Ranger Regiment, Ft. Benning, GA ♣ Specialized Skills: direct action, unconventional warfare, special reconnaissance, interrogations specialist, psychological warfare ♣ First in Command. Responsible for ensuring and maintaining operational readiness. ♣ Height: 6’ ♣ Weight: 195lbs ♣ Combat Experience: Operation Gothic Serpent, Somalia. Operation Desert Storm, OIF, Operation Crescent Wind, Operation Rhino, Operation Anaconda, Operation Jacana, Operation Mountain Viper, Operation Eagle Fury, Operation Condor, Operation Summit, Operation Volcano, Operation Achilles Lindsay Cross Resurrection River 4 HUNTER JAMES: Warrant Officer, Detachment Commander ♣ Recruited from the 75th Ranger Regiment, Ft. Benning, GA ♣ Specialized Skills: direct action, unconventional warfare, special reconnaissance, psychological warfare ♣ Responsible for overseeing all Team ops. Commands in absence of detachment commander. ♣ Height: 6’3” ♣ Weight: 230lbs ♣ Combat Experience: Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Crescent Wind, Operation Anaconda, Operation Jacana, Operation Mountain Viper RANGER JAMES: Team Daddy/Team Sergeant, Master Sgt. -

War in Afghanistan (2001‒Present)

War in Afghanistan (2001–present) 1 War in Afghanistan (2001–present) The War in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001,[1] as the armed forces of the United States and the United Kingdom, and the Afghan United Front (Northern Alliance), launched Operation Enduring Freedom in response to the September 11 attacks on the United States, with the stated goal of dismantling the Al-Qaeda terrorist organization and ending its use of Afghanistan as a base. The United States also said that it would remove the Taliban regime from power and create a viable democratic state. The preludes to the war were the assassination of anti-Taliban leader Ahmad Shah Massoud on September 9, 2001, and the September 11 attacks on the United States, in which nearly 3000 civilians lost their lives in New York City, Washington D.C. and Pennsylvania, The United States identified members of al-Qaeda, an organization based in, operating out of and allied with the Taliban's Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, as the perpetrators of the attacks. In the first phase of Operation Enduring Freedom, ground forces of the Afghan United Front working with U.S. and British Special Forces and with massive U.S. air support, ousted the Taliban regime from power in Kabul and most of Afghanistan in a matter of weeks. Most of the senior Taliban leadership fled to neighboring Pakistan. The democratic Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was established and an interim government under Hamid Karzai was created which was also democratically elected by the Afghan people in the 2004 general elections. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council at the end of December 2001 to secure Kabul and the surrounding areas.