The World's Best Poetry, Volume IX: of Tragedy: of Humour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pirate Utopias: Moorish Corsairs & European Renegadoes Author: Wilson, Peter Lamborn

1111111 Ullllilim mil 1IIII 111/ 1111 Sander, Steven TN: 117172 Lending Library: CLU Title: Pirate utopias: Moorish corsairs & European Renegadoes Author: Wilson, Peter Lamborn. Due Date: 05/06/11 Pieces: 1 PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE TIDS LABEL ILL Office Hours: Monday-Friday, 8am to 4:30pm Phone: 909-607-4591 h«p:llclaremontmiad.oclc.org/iDiadllogon.bbnl PII\ATE UTOPIAS MOORISH CORSAIRS & EUROPEAN I\ENEGADOES PETER LAMBOl\N WILSON AUTONOMEDIA PT o( W5,5 LiaoS ACK.NOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the New York Public Library, which at some time somehow acquired a huge pirate-lit col lection; the Libertarian Book Club's Anarchist Forums, and T A8LE OF CONTENTS the New York Open Center. where early versions were audi ence-tested; the late Larry Law, for his little pamphlet on Captain Mission; Miss Twomey of the Cork Historical I PIl\ATE AND MEl\MAlD 7 Sociel;y Library. for Irish material; Jim Koehnline for art. as n A CHl\ISTIAN TUl\N'D TUl\K 11 always; Jim Fleming. ditto; Megan Raddant and Ben 27 Meyers. for their limitless capacity for toil; and the Wuson ill DEMOCI\.ACY BY ASSASSINATION Family Trust, thanks to which I am "independently poor" and ... IV A COMPANY OF l\OGUES 39 free to pursue such fancies. V AN ALABASTEl\ PALACE IN TUNISIA 51 DEDlCATION: VI THE MOOI\.ISH l\EPU8LlC OF SALE 71 For Bob Quinn & Gordon Campbell, Irish Atlanteans VII MUI\.AD l\EIS AND THE SACK OF BALTIMOl\E 93 ISBN 1-57027-158-5 VIII THE COI\.SAIl\'S CALENDAl\ 143 ¢ Anti-copyright 1995, 2003. -

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and His Children: a Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonz

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his Children: A Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonzalez, Ph.D. Chairperson: Stephen Prickett, Ph.D. The children of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hartley, Derwent, and Sara, have received limited scholarly attention, though all were important nineteenth century figures. Lack of scholarly attention on them can be blamed on their father, who has so overshadowed his children that their value has been relegated to what they can reveal about him, the literary genius. Scholars who have studied the children for these purposes all assume familial ties justify their basic premise, that Coleridge can be understood by examining the children he raised. But in this case, the assumption is false; Coleridge had little interaction with his children overall, and the task of raising them was left to their mother, Sara, her sister Edith, and Edith’s husband, Robert Southey. While studies of S. T. C.’s children that seek to provide information about him are fruitless, more productive scholarly work can be done examining the lives and contributions of Hartley, Derwent, and Sara to their age. This dissertation is a starting point for reinvestigating Coleridge’s children and analyzes their life and work. Taken out from under the shadow of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, we find that Hartley was not doomed to be a “child of romanticism” as a result of his father’s experimental approach to his education; rather, he chose this persona for himself. Conversely, Derwent is the black sheep of the family and consciously chooses not to undertake the family profession, writing poetry. -

Di Tod Browning. Freaks: Da Cut Movie a Cult Movie

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Storia delle arti e conservazione dei beni artistici. Tesi di Laurea La pellicola “maudit” di Tod Browning. Freaks: da cut movie a cult movie. Relatore Prof. Fabrizio Borin Correlatore Prof. Carmelo Alberti Laureando Giulia Brondin Matricola 815604 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Ringrazio il Prof. Fabrizio Borin Thomas mamma, papà, Martina Indice Introduzione........................................................................................................ pag. 3 1. Mostri 1.Mostri e Portenti........................................................................................... » 8 2. Freak Show.................................................................................................. » 30 2. La pellicola “maudit” 1. Il cinema dei mostri.................................................................................... » 42 2. Freaks: Tod Browning................................................................................ » 52 2.1. Brevi considerazioni................................................................................ » 117 3. Un rifiuto durato trent’anni......................................................................... » 123 4. Il piccolo contro il grande............................................................................ » 134 5. La pellicola ambulante: morte e rinascita................................................... » 135 3. Da cut movie a cult movie 1. Freak out!..................................................................................................... -

Edward George Earle Bulwer

EDWARD GEORGE EARLE “IT WAS A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT” BULWER-LYTTON, 1ST BARON LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Edward Bulwer-Lytton HDT WHAT? INDEX EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON 1803 May 25, Wednesday: Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton, 1st baron Lytton was born in London to General William Earle Bulwer of Heydon Hall and Wood Dalling, Norfolk and Elizabeth Barbara Lytton, daughter of Richard Warburton Lytton of Knebworth, Hertfordshire. (His name as assigned at birth was Edward George Earle Bulwer.) The Reverend William Emerson, pastor of the 1st Church of Boston, attended the Election Day sermon of another reverend and then dined with the governor of Massachusetts. When he returned to his parsonage he was informed of the women’s business of that day: his wife Ruth Haskins Emerson had been giving birth in Boston and the apparently healthy infant had been a manchild. The baby would be christened Ralph, after a remote uncle, and Waldo, after a family into which the Emerson family had married in the 17th century.1 (That family had been so named because it had originated with some Waldensians who had become London merchants — but in the current religious preoccupations of the Emerson family there was no trace remaining of the tradition of that Waldensianism.) WALDENSES WALDO EMERSON WALDO’S RELATIVES NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT 1. Great-Great-Grandmother Rebecca Waldo of Chelmsford (born in 1662, married Edward Emerson of Newbury, died 1752); Great-Great-Great Grandfather Deacon Cornelius Waldo (born circa 1624, died January 3?, 1700 in Chelmsford) HDT WHAT? INDEX EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON 1807 Edward George Earle Bulwer’s father died while he was four years of age, and the family relocated to London. -

The Abhorred Name of Turk”: Muslims and the Politics of Identity in Seventeenth- Century English Broadside Ballads

“The Abhorred Name of Turk”: Muslims and the Politics of Identity in Seventeenth- Century English Broadside Ballads A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Katie Sue Sisneros IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Nabil Matar, adviser November 2016 Copyright 2016 by Katie Sue Sisneros Acknowledgments Dissertation writing would be an overwhelmingly isolating process without a veritable army of support (at least, I felt like I needed an army). I’d like to acknowledge a few very important people, without whom I’d probably be crying in a corner, having only typed “My Dissertation” in bold in a word document and spending the subsequent six years fiddling with margins and font size. I’ve had an amazing committee behind me: John Watkins and Katherine Scheil braved countless emails and conversations, in varying levels of panic, and offered such kind, thoughtful, and eye-opening commentary on my work that I often wonder what I ever did to deserve their time and attention. And Giancarlo Casale’s expertise in Ottoman history has proven to be equal parts inspiring and intimidating. Also, a big thank you to Julia Schleck, under whom I worked during my Masters degree, whose work was the inspiration for my entry into Anglo-Muslim studies. The bulk of my dissertation work would have been impossible (this is not an exaggeration) without access to one of the most astounding digital archives I’ve ever seen. The English Broadside Ballad Archive, maintained by the Early Modern Center in the English Department at the University of California, Santa Barbara, has changed markedly over the course of the eight or so years I’ve been using it, and the tireless work of its director Patricia Fumerton and the whole EBBA team has made it as comprehensive and intuitive a collection as any scholar could ask for. -

A Chronological History Oe Seattle from 1850 to 1897

A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OE SEATTLE FROM 1850 TO 1897 PREPARED IN 1900 AND 1901 BT THOMAS W. PROSCH * * * tlBLS OF COIfJI'tS mm FAOE M*E PASS Prior to 1350 1 1875 225 1850 17 1874 251 1351 22 1875 254 1852 27 1S76 259 1855 58 1877 245 1854 47 1878 251 1SSS 65 1879 256 1356 77 1830 262 1357 87 1831 270 1358 95 1882 278 1859 105 1383 295 1360 112 1884 508 1861 121 1385 520 1862 i52 1886 5S5 1865 153 1887 542 1364 147 1888 551 1365 153 1883 562 1366 168 1390 577 1867 178 1391 595 1368 186 1892 407 1369 192 1805 424 1370 193 1894 441 1871 207 1895 457 1872 214 1896 474 Apostolus Valerianus, a Greek navigator in tho service of the Viceroy of Mexico, is supposed in 1592, to have discov ered and sailed through the Strait of Fuca, Gulf of Georgia, and into the Pacific Ocean north of Vancouver1 s Island. He was known by the name of Juan de Fuca, and the name was subsequently given to a portion of the waters he discovered. As far as known he made no official report of his discoveries, but he told navi gators, and from these men has descended to us the knowledge thereof. Richard Hakluyt, in 1600, gave some account of Fuca and his voyages and discoveries. Michael Locke, in 1625, pub lished the following statement in England. "I met in Venice in 1596 an old Greek mariner called Juan de Fuca, but whose real name was Apostolus Valerianus, who detailed that in 1592 he sailed in a small caravel from Mexico in the service of Spain along the coast of Mexico and California, until he came to the latitude of 47 degrees, and there finding the land trended north and northeast, and also east and south east, with a broad inlet of seas between 47 and 48 degrees of latitude, he entered therein, sailing more than twenty days, and at the entrance of said strait there is on the northwest coast thereto a great headland or island, with an exceeding high pinacle or spiral rock, like a pillar thereon." Fuca also reported find ing various inlets and divers islands; describes the natives as dressed in skins, and as being so hostile that he was glad to get away. -

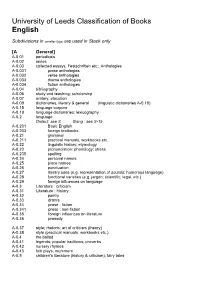

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

The Stolen Village: Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE STOLEN VILLAGE: BALTIMORE AND THE BARBARY PIRATES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Des Ekin | 488 pages | 31 Dec 2008 | O'Brien Press Ltd | 9781847171047 | English | Dublin, Ireland The Stolen Village: Baltimore and the Barbary Pirates PDF Book Did anyone assist the pirates? More than 20, captives were said to be imprisoned in Algiers alone. Download as PDF Printable version. No trivia or quizzes yet. In a Royal Navy squadron led by Sir John Narborough negotiated a lasting peace with Tunis and, after bombarding the city to induce compliance, with Tripoli. The slaves typically had to stand from eight in the morning until two in the afternoon while buyers viewed them. Escape the Present with These 24 Historical Romances. That's what you get from too much fiction, I guess. Published on. The adventures of the few who escaped; the punishments inflicted At night the slaves were put into prisons called ' bagnios ' derived from the Italian word "bagno" for public bath , inspired by the Turks' use of Roman baths at Constantinople as prisons , [31] which were often hot and overcrowded. Namespaces Article Talk. And makes his choice of words to describe the raid even more regrettable. Irish and English national and local histories of the period are reviewed too. The author was able to tell a great story, from facts and his very intense original source research. This beautiful book visits twenty-eight richly atmospheric sites and tells the mythological stories associated with them. Retrieved 27 March The Sack of Baltimore was the most devastating invasion ever mounted by Islamist forces on Ireland or England. -

Guide to Archaeological and Architectural Heritage Sources in Cork City & County

A Guide to Archaeological and Architectural Heritage Sources in Cork City & County COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL Introduction his bibliography has been prepared as an aid to those engaged in Tresearch on the archaeological and architectural heritage of Cork City and County. It is particularly aimed at assisting research, undertaken as part of planning proposals, which have the potential to impact upon the architectural and archaeological heritage. It will also serve as a useful data source for those engaged in developing strategic development policies for the city and county. While this list of sources is not exhaustive, it should serve as a useful starting point for those engaged in research for both the City and County. The sources outlined in this bibliography relate specifically to Cork City and County or contain substantial sections which are of relevance to same. The first section of this document identifies the main repositories of information and lists their most important collections of relevance. Key primary and secondary references follow, including maps and photographic archives, books, historical journals, academic papers and other research pertaining to the city and county. Settlement-specific references have been provided for the main towns within the county area. The preparation of this bibliography was funded by the Heritage Council, Cork County Council and Cork City Council as an action of the County and City Heritage Plans. The bibliography was compiled by John Cronin and Associates and edited by the project steering committee. For more information contact Cork City Council at [email protected] and Cork County Council at [email protected] Sources for the Archaeological and Architectural Heritage of Cork City & County page 1 of 1 Additional Information Repositories of Information Cork City and County Archives Solicitors' and Landed Estate Papers Seamus Murphy Building, • Colthursts of Blarney Estate (1677) (1800-1943). -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, Number 3

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 51 Number 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 51, Article 1 Number 3 1972 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, Number 3 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1972) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, Number 3," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 51 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol51/iss3/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, Number 3 Published by STARS, 1972 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51 [1972], No. 3, Art. 1 COVER Cedar Key, at the time this lithograph was made in 1884, was in the midst of an economic boom. Settled in 1842 by Judge Augustus Steele, the Cedar Keys were at first a summer resort. In 1855 Eberhard Farber acquired land in nearby Gulf Hammock and set up a sawmill at Cedar Key to saw logs for his pencil factories in Germany and New Jersey. In 1860 Cedar Key became the terminus for the Florida Railroad. After the Civil War the community expanded and broadened its economic base. Turtles, sponges, and fish were being exported in large quantities by the 1880s, as well as pine and cedar logs and lumber. The U. S. Customs House was moved to Cedar Key from St. -

Lost Silent Feature Films

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 11/16/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) Ableminded Lady, -

Literature and Americana

Catalogue 28 Literature and Americana Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada Catalogue Twenty-Eight Literature and Americana from Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada All items subject to prior sale. Shipping is extra and will billed at or near cost. Payment may be made with a check, PayPal, Visa, Mastercard, Discover. We will cheerfully work with institu- tions to accommodate accounting policies/constraints. Any item found to be disappointing may be returned within a week of receipt; please notify us if this is happening or if you need more time. Direct enquiries to: Mark Stirling, Up-Country Letters. PO Box 596, Gardnerville, NV 89410 530 318-4787 (cell); 775 392-1122 (land line) [email protected] www.upcole.com Christie Macdonald Jefferson Star of the musical stage in the early 1900’s, she married William W. Jefferson, son of the actor Joseph Jefferson, in 1901. “I am strong and self-reliant enough to make myself what I wish to be.” See Item 78 The cover: Map of the State of Nevada, 1866. Department of the Interi- or, General Land Office. See Item 51. Dedication copy, see Item 43 Hampshire) Library on the free endpaper of each volume, no other library markings. Light rub- 1. Arnold, Matthew. Carte de Visite Photograph. Imprint of Elliott and Fry. Bust portrait. bing, a little spotting and wrinkling, but a Fine, fresh copy. $100 Contemporary ownership initials dated May, 1868. The National Portrait Gallery lists this pose as 1870's. A Fine copy. $100 8. [California, Emigrant Trail] Smith, C.W. (Charles). Journal of a Trip to California.