J Surveys 1820-32 IX Eng. Ref.Legislation.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

24 Mar 2020 Page 1 Root AAA #2468, B. ___1600,1,2,3,4,5,6,7

24 Mar 2020 Page 1 Root AAA #2468, b. __ ___ 1600,1,2,3,4,5,6,7. This is a place holder name for general information. - See the sources for this name for citation examples. - Use the 'Occupation' tag for the general source for a person. Put a '.' in the field to ensure the source is printed in reports. The word 'occupation' is translated to 'general source' in the indented book report. I. Alcock AAA #2387. A.James Alcock #16, d. 22 May 1887.8 . He married Mary Ann French #17 (daughter of Joseph French #402 and Welsh bride ... #576). Mary: Mother Welsh. 1. James Alcock #14, b. 16 Jan 1856 in Harbour Grace,8 d. 25 Jun 1895,9 buried in Ch.of England, Harbour Grace. Listed as a fisherman living on Water Street West, St. John's at time of dau. Marion's baptism.10 He married Annie Liza Pike #15, b. 17 Mar 1859 in Mosquito Cove (Bristol's Hope) (daughter of Moses Pike #18 and Patience Cake #19), d. 25 Oct 1932, buried in Ch. of England, Harbour Grace. a. John Alcock #49, b. 28 Jul 1884 in Harbour Grace, buried in Ch of England, Harbour Grace, d. 27 Oct 1905. Never Married. b. Marion (May) Alcock #117, b. 25 Feb 1887 in Harbour Grace,11 baptized 29 Apr 1887,11 d. 25 Mar 1965,12 buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery, St. John's,12 occupation .13 . [CR] Marion and Harold lived on Water Street, Harbour Grace. [MGF] Postcard from Hubert Garland to Marion (May) in 1914 was addressed to Ships Head. -

The World's Best Poetry, Volume IX: of Tragedy: of Humour

Title: The World's Best Poetry, Volume IX: Of Tragedy: of Humour Author: Various Contributor: Francis Barton Gummere Editor: Bliss Carman Release Date: July 15, 2013 [EBook #43223] Language: English _THE WORLD'S_ _BEST POETRY_ _I Home: Friendship_ _VI Fancy: Sentiment_ _II Love_ _VII Descriptive: Narrative_ _III Sorrow and Consolation_ _VIII National Spirit_ _IV The Higher Life_ _IX Tragedy: Humor_ _V Nature_ _X Poetical Quotations_ _THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY_ _IN TEN VOLUMES, ILLUSTRATED_ _Editor-in-Chief BLISS CARMAN_ _Associate Editors_ _John Vance Cheney Charles G. D. Roberts_ _Charles F. Richardson Francis H. Stoddard_ _Managing Editor: John R. Howard_ [Illustration] _JOHN D. MORRIS AND COMPANY PHILADELPHIA_ COPYRIGHT, 1904, BY JOHN D. MORRIS & COMPANY [Illustration: JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE. _Photogravure after portrait by Stieler._] _The World's Best Poetry_ _Vol. IX_ _Of TRAGEDY:_ _of HUMOR_ _THE OLD CASE OF_ _POETRY_ _IN A NEW COURT_ _By_ _FRANCIS A. GUMMERE_ [Illustration] _JOHN D. MORRIS AND COMPANY_ _PHILADELPHIA_ COPYRIGHT, 1904, BY John D. Morris & Company NOTICE OF COPYRIGHTS. I. American poems in this volume within the legal protection of copyright are used by the courteous permission of the owners,--either the publishers named in the following list or the authors or their representatives in the subsequent one,--who reserve all their rights. So far as practicable, permission has been secured, also for poems out of copyright. PUBLISHERS OF THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY. 1904. The BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY, Indianapolis.--F. L. STANTON: "Plantation Ditty." The CENTURY CO., New York.--_I. Russell_: "De Fust Banjo," "Nebuchadnezzar." Messrs. HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.--_W. A. -

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and His Children: a Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonz

ABSTRACT Genius, Heredity, and Family Dynamics. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his Children: A Literary Biography Yolanda J. Gonzalez, Ph.D. Chairperson: Stephen Prickett, Ph.D. The children of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hartley, Derwent, and Sara, have received limited scholarly attention, though all were important nineteenth century figures. Lack of scholarly attention on them can be blamed on their father, who has so overshadowed his children that their value has been relegated to what they can reveal about him, the literary genius. Scholars who have studied the children for these purposes all assume familial ties justify their basic premise, that Coleridge can be understood by examining the children he raised. But in this case, the assumption is false; Coleridge had little interaction with his children overall, and the task of raising them was left to their mother, Sara, her sister Edith, and Edith’s husband, Robert Southey. While studies of S. T. C.’s children that seek to provide information about him are fruitless, more productive scholarly work can be done examining the lives and contributions of Hartley, Derwent, and Sara to their age. This dissertation is a starting point for reinvestigating Coleridge’s children and analyzes their life and work. Taken out from under the shadow of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, we find that Hartley was not doomed to be a “child of romanticism” as a result of his father’s experimental approach to his education; rather, he chose this persona for himself. Conversely, Derwent is the black sheep of the family and consciously chooses not to undertake the family profession, writing poetry. -

Edward George Earle Bulwer

EDWARD GEORGE EARLE “IT WAS A DARK AND STORMY NIGHT” BULWER-LYTTON, 1ST BARON LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Edward Bulwer-Lytton HDT WHAT? INDEX EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON 1803 May 25, Wednesday: Edward George Earle Bulwer-Lytton, 1st baron Lytton was born in London to General William Earle Bulwer of Heydon Hall and Wood Dalling, Norfolk and Elizabeth Barbara Lytton, daughter of Richard Warburton Lytton of Knebworth, Hertfordshire. (His name as assigned at birth was Edward George Earle Bulwer.) The Reverend William Emerson, pastor of the 1st Church of Boston, attended the Election Day sermon of another reverend and then dined with the governor of Massachusetts. When he returned to his parsonage he was informed of the women’s business of that day: his wife Ruth Haskins Emerson had been giving birth in Boston and the apparently healthy infant had been a manchild. The baby would be christened Ralph, after a remote uncle, and Waldo, after a family into which the Emerson family had married in the 17th century.1 (That family had been so named because it had originated with some Waldensians who had become London merchants — but in the current religious preoccupations of the Emerson family there was no trace remaining of the tradition of that Waldensianism.) WALDENSES WALDO EMERSON WALDO’S RELATIVES NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT 1. Great-Great-Grandmother Rebecca Waldo of Chelmsford (born in 1662, married Edward Emerson of Newbury, died 1752); Great-Great-Great Grandfather Deacon Cornelius Waldo (born circa 1624, died January 3?, 1700 in Chelmsford) HDT WHAT? INDEX EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON 1807 Edward George Earle Bulwer’s father died while he was four years of age, and the family relocated to London. -

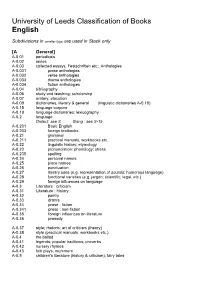

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

Literature and Americana

Catalogue 28 Literature and Americana Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada Catalogue Twenty-Eight Literature and Americana from Up-Country Letters Gardnerville, Nevada All items subject to prior sale. Shipping is extra and will billed at or near cost. Payment may be made with a check, PayPal, Visa, Mastercard, Discover. We will cheerfully work with institu- tions to accommodate accounting policies/constraints. Any item found to be disappointing may be returned within a week of receipt; please notify us if this is happening or if you need more time. Direct enquiries to: Mark Stirling, Up-Country Letters. PO Box 596, Gardnerville, NV 89410 530 318-4787 (cell); 775 392-1122 (land line) [email protected] www.upcole.com Christie Macdonald Jefferson Star of the musical stage in the early 1900’s, she married William W. Jefferson, son of the actor Joseph Jefferson, in 1901. “I am strong and self-reliant enough to make myself what I wish to be.” See Item 78 The cover: Map of the State of Nevada, 1866. Department of the Interi- or, General Land Office. See Item 51. Dedication copy, see Item 43 Hampshire) Library on the free endpaper of each volume, no other library markings. Light rub- 1. Arnold, Matthew. Carte de Visite Photograph. Imprint of Elliott and Fry. Bust portrait. bing, a little spotting and wrinkling, but a Fine, fresh copy. $100 Contemporary ownership initials dated May, 1868. The National Portrait Gallery lists this pose as 1870's. A Fine copy. $100 8. [California, Emigrant Trail] Smith, C.W. (Charles). Journal of a Trip to California. -

Garland #33 B. __ ___ 1640, Ref .,1 M

14 Feb 1999 Page 1 Joseph (John?) Garland #33 b. __ ___ 1640, ref .,1 m. Sarah ... #34. Joseph died __ ___ 1732,2 . 3 Farmer of East Lulworth, Dorset, England. Letter dated August 27, 1996, from Gordon Hancock, who researched the Garland-Lester line, felt that Joseph should be John but could not recall why. I. John Garland #1216 ref . 1 II. Joseph Garland #35 ref . 4 [MMPD] Substantial yeoman farmer, East Chaldon. A. John Garland #153 b. __ ___ 1746, d. __ ___ 1781.2 B. Sarah Garland #150 m. R. Robinson #905, ref . 1 Sarah died __ ___ 1797.2 1. Joseph Robinson #908 ref . 1 2. George Richard Robinson #909 ref . 1 Nfld. Merchant. C. Mary Garland #155 b. __ ___ 1748,1 m. Marmaduke Hart #914, ref . 1 Mary died __ ___ 1840.1 D. Joseph Garland #149 b. __ ___ 1750, ref .,1 d. __ ___ 1839.2 Nfld. Merchant. [MMPD] Came to Nfld. with brother George to set up corn trade. 1. Joseph Garland #906 ref . 1 2. John Garland #907 ref . 1 E. George Garland #151 b. __ ___ 1753, East Lulworth, England,5 m. __ ___ 1799,5 Amy Lester #152, b. __ ___ 1759, (daughter of Benjamin Lester #660 and Susannah Tavener #661) d. __ ___ 1819. George died __ ___ 1825, Wimborne, England.5 [RIGGS] Inherited from his father-in-law, Benjamin Lester, one of the largest and most prosperous mercantile establishments involved in the Nfld. fish trade. Company was based in Poole, with Nfld HQ in Trinity. [ref CUFF] George established business on his own account in 1805. -

Mark Pack Submitted for the Degree of Dphil York University History Department June1995 Appendix 1: Borough Classifications

Aspects of the English electoral system 1800-50, with special reference to Yorkshire. Volume 2 of 2 Mark Pack submitted for the degree of DPhil York University History Department June1995 Appendix 1: Borough classifications ' There are several existing classifications of boroughs by franchise type. I have preferred to construct my own as there are clear problems with the existing classifications, such as inconsistencies and some errors (e.g. see Malton below). In this context, it is more satisfying to delve into the issue, rather than simply pick one of the existing classifications off the shelf. This is particularly so given the existence of a much under-used source of evidence: post-1832 electoral registers (or sources that contain information about them). Under certain conditions pre-1832 franchises were allowed to continue after 1832. As electoral registers listed what qualifications people had registered under, post-1832 registers can reveal the pre-1832 franchise. That at least is the theory; there are some complicating factors. First, the description in an electoral register may be less than a complete description of the pre-1832 franchise. For example, if a register says "freemen" one does not know if there had been additional requirements, such as having to be resident. Second, not all pre-1832 constituencies survived, and so there are no electoral registers for these. Third, compilers of electoral registers may have got the pre-1832 franchise wrong. This is unlikely as when the first registers were being drawn up in the 1830s there was a wealth of local and verbal knowledge to consult. -

Ellis Wasson the British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2

Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Ellis Wasson The British and Irish Ruling Class 1660-1945 Volume 2 Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński ISBN 978-3-11-056238-5 e-ISBN 978-3-11-056239-2 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2017 Ellis Wasson Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Michalak Associate Editor: Łukasz Połczyński www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Thinkstock/bwzenith Contents The Entries VII Abbreviations IX List of Parliamentary Families 1 Bibliography 619 Appendices Appendix I. Families not Included in the Main List 627 Appendix II. List of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 648 Indexes Index I. Index of Titles and Family Names 711 Index II. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by Country 769 Index III. Seats of Parliamentary Families Organized by County 839 The Entries “ORIGINS”: Where reliable information is available about the first entry of the family into the gentry, the date of the purchase of land or holding of office is provided. When possible, the source of the wealth that enabled the family’s election to Parliament for the first time is identified. Inheritance of property that supported participation in Parliament is delineated. -

Verse in New Monthly Magazine

Curran Index - Table of Contents Listing New Monthly Magazine For a general introduction to and attribution listing of prose for The New Monthly Magazine see the Wellesley Index, Volume III, pages 161-302. The Curran Index includes additions and corrections to that listing, as well as a listing of poetry published between 1821 and 1854. EDITORS: Writing of Francis Foster Barham, both the DNB and the new Oxford DNB incorrectly claim that Barham and John Abraham Heraud edited NMM. In fact, neither man was at any time or in any way connected with NMM. The error apparently can be traced to A Memorial of Francis Barham, ed. Isaac Pitman, published in London in 1873, two years after Barham’s death, and it can be explained by a study of capitalization: what Barham and Heraud edited was a new series of the Monthly Magazine, not the New Monthly (the DNB has it right in its biography of Heraud). The third and final series of the Monthly, with a minimal change in its sub-title, started in 1839, with Barham and Heraud as its editors; Barham stayed only a year as editor, Heraud three years. See Kenneth Curry, ‘The Monthly Magazine,’ in British Literary Magazines. The Romantic Age, 1789-1836, ed. Alvin Sullivan, 314-319. In applications for RLF aid (case 1167), Heraud repeatedly claimed editorship of and frequent contributions to the Monthly but never mentioned the New Monthly. [This note clarifies and supersedes that in VPR 28 (1995), 291.] [12/07] Editorship. Wellesley 3:169 gives dates of Cyrus Redding’s sub-editorship as February 1821 - September 1830; those of S. -

RESPONSES to BYRON in the WORKS of THREE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVELISTS: Carol Anne White a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with Th

RESPONSES TO BYRON IN THE WORKS OF THREE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVELISTS: Carol Anne White A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosphy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto @copyright by Carol White, 1997 National tibrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abetract Responsee to Byron in the Works of Three Nineteenth-Century Novelists: Edward Bulwer, Charles Dickens and Charlotte Brontë Ph-D., 1997 Carol Anne White Graduate Department of English, University of Toronto Andrew Elfenbein's Byron and the Victorians(l995) is a full-length account of Victorian response to Byron and Byronism. This thesis builds upon his work by examining how three nineteenth-century novelists, Edward Bulwer, Charles Dickens and Charlotte Brontë, responded to Byron in their fiction. -

The Poets and Poetry of the Nineteenth Century

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES The Poets and the Poetry of the Nineteenth Century £0}C (poets ant t$i (poettg of f$e QXtnefeenf^ Century (HUMOUR) K - George Crabbe to Edmund B. V. Christian Edited by ALFRED H. MILES LONDON GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS, LTD. New York: E. P. DUTTON & CO. In the prefatory note of the first edition of this work (1S91) the Editor invited criticism with a view to the improvement of future editions. Several critics responded to this appeal, and their valuable sugges- tions have been considered in pre- paring this re-issue. In some cases the text has been revised and the selection in varied ; others, addi- tions have been made to complete the representation. The biographi- cal and bibliographical matter ha= been brought up to date. —A.H.M. PREFATORY. This volume is devoted to the Humorous poetry of the century. With a view to the thorough representation of the humorous element in the poetic literature of the period, selections are included from the works of the general poets whose humorous verse bears sufficient proportion to the general body of their poetry, or is sufficiently characteristic to demand separate representation, as well as from the works of those exclusively humorous writers whose verse is the raison d'etre of the volume. The Editor's thanks are due to Messrs. William Blackwood & Son for permission to include two of " " the Legal Lyrics of the late George Outram, and a selection from "The Bon Gaultier Ballads" of late E. Sir Theodore Martin and the W.