Verse in New Monthly Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF EPUB} Rejected Addresses: and Other Poems by James Smith

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rejected addresses: and other poems by James Smith Jun 25, 2010 · Rejected addresses, and other poems Paperback – June 25, 2010 by Epes Sargent (Author), Horace Smith (Author), James Smith (Author) › Visit Amazon's James Smith Page. Find all the books, read about the author, and more. See search results for this author. Are you an author?Author: Epes Sargent, Horace Smith, James SmithFormat: PaperbackRejected Addresses, and other poems. ... With portraits ...https://www.amazon.com/Rejected-Addresses...Rejected Addresses, and other poems. ... With portraits and a biographical sketch. Edited by E. Sargent. [Smith, James, Sargent, Epes, Smith, Horatio] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Rejected Addresses, and other poems. ... With portraits and a biographical sketch. Edited by E. Sargent. Jun 22, 2008 · Rejected Addresses: And Other Poems by James Smith, Horace Smith. Publication date 1871 Publisher G. P. Putnam & sons Collection americana Digitizing sponsor Google Book from the collections of University of Michigan Language English.Pages: 441Rejected Addresses, and other poems. ... With portraits ...https://books.apple.com/us/book/rejected-addresses...The POETRY & DRAMA collection includes books from the British Library digitised by Microsoft. The books reflect the complex and changing role of literature in society, ranging from Bardic poetry to Victorian verse. Containing many classic works from important dramatists and poets, this collectio… Rejected addresses, and other poems Item Preview remove-circle Share or Embed This Item. EMBED. EMBED (for wordpress.com hosted blogs and archive.org item <description> tags) Want more? Advanced embedding details, examples, and help! ...Pages: 460Rejected addresses, and other poems. -

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

L-G-0013245003-0036967409.Pdf

A History of Romantic Literature BLACKWELL HISTORIES OF LITERATURE General editor: Peter Brown, University of Kent, Canterbury The books in this series renew and redefine a familiar form by recognizing that to write literary history involves more than placing texts in chronological sequence. Thus the emphasis within each volume falls both on plotting the significant literary developments of a given period, and on the wider cultural contexts within which they occurred. ‘Cultural history’ is construed in broad terms and authors address such issues as politics, society, the arts, ideologies, varieties of literary production and consumption, and dominant genres and modes. The effect of each volume is to give the reader a sense of possessing a crucial sector of literary terrain, of understanding the forces that give a period its distinctive cast, and of seeing how writing of a given period impacts on, and is shaped by, its cultural circumstances. Published to date Seventeenth‐Century English Literature Thomas N. Corns Victorian Literature James Eli Adams Old English Literature, Second Edition R. D. Fulk and Christopher M. Cain Modernist Literature Andrzej Gąsiorek Eighteenth‐Century British Literature John Richetti Romantic Literature Frederick Burwick A HISTORY OF ROMANTIC LITERATURE Frederick Burwick This edition first published 2019 © 2019 John Wiley & Sons Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

Horace Smith - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace Smith - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace Smith(31 December 1779 - 12 July 1849) Horace (born Horatio) Smith was an English poet and novelist, perhaps best known for his participation in a sonnet-writing competition with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/percy-bysshe-shelley/">Percy Bysshe Shelley</a>. It was of him that Shelley said: "Is it not odd that the only truly generous person I ever knew who had money enough to be generous with should be a stockbroker? He writes poetry and pastoral dramas and yet knows how to make money, and does make it, and is still generous." <b>Biography</b> Smith was born in London, the son of a London solicitor, and the fifth of eight children. He was educated at Chigwell School with his elder brother James Smith, also a writer. Horace first came to public attention in 1812 when he and his brother James (four years older than he) produced a popular literary parody connected to the rebuilding of the Drury Lane Theatre, after a fire in which it had been burnt down. The managers offered a prize of £50 for an address to be recited at the Theatre's reopening in October. The Smith brothers hit on the idea of pretending that the most popular poets of the day had entered the competition and writing a book of addresses rejected from the competition in parody of their various styles. James wrote the parodies of Wordsworth, Southey, Coleridge and Crabbe, and Horace took on Byron, Moore, Scott and Bowles. -

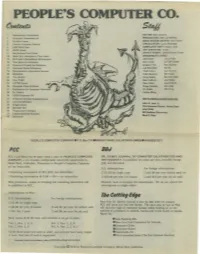

People's Computer Co

PEOPLE'S COMPUTER CO. ~~ Stall 1 Subscription Information EDITOR: Bob Albrecht 2 Computer Awareness lab PRODUCTION: Mary Jo McPhee 3 Comfort House BOOK REVIEW EDITOR: Dan Rosset , Trenton Computer Festival CIRCULATION: Laura Reininger , FORTRAN Man COMPLAINT DEPT: Happy Lady 6 BASIC Music ART DIRECTOR: Dover 9 San Andreas Fault Caper STRAIT FRONT: LeRoy Phillip Finkel 10 World As a Holcq<lm in Your Heart DRAGONS-AT·LARGE Bill fuller's Biofeedback Bibliography John Snell Larry Press l' YOlX Brain is a Hologram Oon Inman LO ·OP Center 16l' Electronic Projects for Musicians Gregory Yob Mac Oglesby 17 Computer Music References Lee Schneider NeTM 18 Minicalculator Information Sources Todd Voros Kurt Inman 20 S!NNERS Peter Sessions Bill Fuller 22 Tiny BASIC Doug Seeley Sprocket Man 23 Tiny TREK Marc LeBrun Joel Miller 2' LO·OP Center Dean Kahn Joyce Hatch 26 Computer Clubs & Stores Roger Hen5tey Sol Libes 27 Publications 101" Computer Dr.Oobb MS. Frog 29 Dr.Oobb's Lichen Wang 30 16 Bit Computer Kit 31 A Musical Number Guessing Game RETAINING SUBSCRIBERS: 32 Los Cost Software John R. Lees, Jr. 33 Dragonsmoke Th. Computer Corner, Harriet Shair 34 Sprocket Man John Ribl. 36 Programmer's Toolbox Bill Godbout ElectroniCl 37 Leters and Other Numbers ""rk S. Elgin 43 BookstOl"e PEOPLE'S COMPUTER COMPANY. P.O. Box 310.MENlO PARK, CALIFORNIA 94025.(415)323-3111 PCC /)/)J PeC is published six Of more times a year by PEOPLE'S COMPUTER DR. DOBS'S JOURNAL OF COMPUTER CALlSTHENT1CS AND COMPANY, a tax exampt, independent non-profit corporation in ORTHODONTIA is published ten times per year, monthly except Menlo Park~ California. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Introduction

Introduction The Ladies, I should tell you, have been dealing largely and profitably at the shop of the Muses. And the Hon. Mrs. Norton ... has been proving that she has some of the true ink in her veins, and has taken down several big boys in Mr. Colburn's Great Burlington School. Mrs. Hemans, too, has been kindly noticed by Mr. Murray, and has accomplished the difficult feat of a second edition. Apollo is beginning to discharge his retinue of sprawling men-servants, and to have handmaids about his immortal person, to dust his rays and polish his bow and fire-irons. If the great He- Creatures intend to get into place again, they must take Mrs. Bramble's advice, and "have an eye to the maids." -John Hamilton Reynolds (1832) Although their influence and even their existence has been largely unac knowledged by literary scholars and critics throughout most of the twentieth century, women poets were, as their contemporary John Hamilton Reynolds nervously acknowledged, a force to be reckoned with in early-nineteenth century Britain.1 Not only Felicia Hemans and Caroline Norton but Letitia Elizabeth Landon and Mary Howitt were major players and serious competi tors in the literary marketplace of Reynolds's time. Their poetry was reviewed in the most prestigious journals, respected by discerning readers, reprinted, imitated, anthologized, sung, memorized for recitation, copied into com monplace books, and bought by the public. Before their time, prominent writers such as Joanna Baillie, Anna Letitia Barbauld, Hannah More, Mary Robinson, Anna Seward, Charlotte Smith, Mary Tighe, and others helped to change the landscape of British poetry both in style and in subject matter. -

The Poets and Poetry of Scotland

THE POETS AND POETRY OF SCOTLAND. PERIOD 1777 TO 1876. THOMAS CAMPBELL Born 1777 — Died 1844. THOMAS CAMPBELL, so justly and himself of the instructions of the celebrated poetically called the "Bard of Hope," was Heyne, and attained such proficiency in Greek bom in High Street, Glasgow, July 27, 1777, and the classics generally that he was re- and was the youngest of a family of eleven garded as one of the best classical scholars of children. His father was connected with good his day. In speaking of his college career, families in Argyleshire, and had carried on a which was extended to five sessions, it is prosperous trade as a Virginian merchant, but worthy of notice that Professor Young, in met with heavy losses at the outbreak of the awarding to Campbell a prize for the best American war. The poet was particularly translation of the Clouds of Aristophanes, pro- fortunate in the. intellectual character of his nounced it to be the best exercise which had parents, his father being the intimate friend of ever been given in by any student belonging the celebrated Dr. Thomas Reid, author of the to the university. In original poetry he Inquiry into the. Human Mind, after whom he was also distinguished above all his class- received his Christian name, while his mother mates, so that in 1793 his "Poem on Descrip- was distinguished by her love of general litera- tion" obtained the prize in the logic class. ture, combined with sound understanding and Amongst his college companions Campbell a refined taste. Campbell afforded early indi- soon became known as a poet and wit; and on cations of genius; as a child he was fond of one occasion, the students having in vain made ballad poetry, and at the age of ten composed repeated application for a holiday' in commem- verses exhibiting the delicate appreciation of oration of some public event, he sent in a peti- the graceful flow and music of language for tion in verse, with which the professor was so which his poetry was afterwards so highly dis- pleased that the holiday was granted in com- tinguished. -

POPES HORATIAN POEMS.Pdf (10.50Mb)

THOMAS E. MARESCA OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS $5.00 POEMS BY THOMAS E. MARESCA Recent critical studies of Alexander Pope have sought to define his poetic accom plishment in terms of a broadened aware ness of what the eighteenth century called wit. That Pope's achievement can be lo cated in wit is still generally agreed; but it now seems clear that the fullest signifi cance of his poetry can be found in the more serious meaning the Augustans at tached to that word: the ability to discern and articulate—to "invent," in the classical sense—the fundamental order of the world, of society, and of man, and to express that order fittingly in poetry. Mr. Maresca maintains that it is Pope's success in this sort of invention that is the manifest accomplishment of his Imitations of Horace. And Mr. Maresca finds that, for these purposes, the Renaissance vision of Horace served Pope well by providing a concordant mixture of rational knowledge and supernatural revelation, reason and faith in harmonious balance, and by offer ing as well all the advantages of applying ancient rules to modern actions. Within the expansive bounds of such traditions Pope succeeded in building the various yet one universe of great poetry. Thomas E. Maresca is assistant professor of English at the Ohio State University, POPE'S POEMS For his epistles, say they, are weighty and powerful; hut his bodily presence is weak, and his speech contemptible. H COR. io: 10 POPE'S HORATIAN POEMS BY THOMAS E. MARESCA OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1966 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 66-23259 MEIS DEBETUR Preface THIS BOOK is an attempt to read some eighteenth-century poems; it is much more a learning experiment on my part than any sort of finished criticism. -

The World's Best Poetry, Volume IX: of Tragedy: of Humour

Title: The World's Best Poetry, Volume IX: Of Tragedy: of Humour Author: Various Contributor: Francis Barton Gummere Editor: Bliss Carman Release Date: July 15, 2013 [EBook #43223] Language: English _THE WORLD'S_ _BEST POETRY_ _I Home: Friendship_ _VI Fancy: Sentiment_ _II Love_ _VII Descriptive: Narrative_ _III Sorrow and Consolation_ _VIII National Spirit_ _IV The Higher Life_ _IX Tragedy: Humor_ _V Nature_ _X Poetical Quotations_ _THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY_ _IN TEN VOLUMES, ILLUSTRATED_ _Editor-in-Chief BLISS CARMAN_ _Associate Editors_ _John Vance Cheney Charles G. D. Roberts_ _Charles F. Richardson Francis H. Stoddard_ _Managing Editor: John R. Howard_ [Illustration] _JOHN D. MORRIS AND COMPANY PHILADELPHIA_ COPYRIGHT, 1904, BY JOHN D. MORRIS & COMPANY [Illustration: JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE. _Photogravure after portrait by Stieler._] _The World's Best Poetry_ _Vol. IX_ _Of TRAGEDY:_ _of HUMOR_ _THE OLD CASE OF_ _POETRY_ _IN A NEW COURT_ _By_ _FRANCIS A. GUMMERE_ [Illustration] _JOHN D. MORRIS AND COMPANY_ _PHILADELPHIA_ COPYRIGHT, 1904, BY John D. Morris & Company NOTICE OF COPYRIGHTS. I. American poems in this volume within the legal protection of copyright are used by the courteous permission of the owners,--either the publishers named in the following list or the authors or their representatives in the subsequent one,--who reserve all their rights. So far as practicable, permission has been secured, also for poems out of copyright. PUBLISHERS OF THE WORLD'S BEST POETRY. 1904. The BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY, Indianapolis.--F. L. STANTON: "Plantation Ditty." The CENTURY CO., New York.--_I. Russell_: "De Fust Banjo," "Nebuchadnezzar." Messrs. HARPER & BROTHERS, New York.--_W. A. -

Miesque's Approval

Miesque’s Approval (USA) bay, 1999 • height 16.0hh Native Dancer - Polynesian Raise A Native Mr Prospector Raise You - Case ace RACE RECORD 1970 Nashua - Nasrullah Gold Digger In USA, 12 wins, 1600-1800m and $2.6 million Sequence - Count Fleet Timeform 130 - Gr1 Breeders Cup Mile Turf Miesque’s Son Champion Turf Horse in USA in 2006 (USA) 1992 NORTHERN DANCER - Nearctic at 2 WON Pilgrim S.-(L) (1800m) Nureyev 2nd Gr2 Summer S. (1600m) Miesque Special - Forli 2nd Gr3 Generous S. (1600m) 1984 Prove Out - Graustark at 3 WON Gr3 Kent S. (1800m) Pasadoble WON Turf Cup Hcp-(L) (1800m) Santa Quilla - Sanctus 2nd Gr3 Hill Prince S. (1800m) Fortino - Grey Sovereign 2nd Gr3 Calder ||Derby (1800m) Caro 3rd Pete Axhelm S.-(L) (1500m) With Approval Chambord - Chamossaire at 4 2nd Gr2 Mile S. (1600m) 1986 Buckpasser - Tom Fool 2nd Gr3 Canadian Turf Hcp (1700m) Passing Mood 2nd Sea O’Erin Mile Hcp (L) (1600m) Win Approval Cool Mood - NORTHERN DANCER at 6 WON Old Ironside S. (L) (1600m) (USA) 1992 Tom Rolfe - Ribot 3rd Carterista Hcp (L) (1700m) Hoist The Flag at 7 WON Gr1 Breeder’s Cup Mile (1600m) Negotiator Wavy Navy - War Admiral WON Gr2 Mile S. (1600m) 1974 Gulf-Weed - Gulf Stream WON Gr2 Firecracker Hcp (1600m) Geneva WON Gr3 Red Bank S. (1600m) Anglofila - Madrigal WON Turf S. (L) (1800m) 2nd Gr1 Canadian Turf Hcp (1700m) STAMINA highest distance of individual winners, 3yo & up FEMALE LINE SIRE LINE 800/1399m 14/1600m 16/1999m 20/2399m 2400m+ 1st dam 39% 39% 12% 6% 4% Win Approval (92f, With Approval): 2 wins in USA; dam of MIESQUE’S SON – multiple Gr1 placed Gr3 winner MIESQUE’S APPROVAL (99c, Miesque’s Son): - in France (TFR 117). -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave".