PDF Download Ancient Roman Technology Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legionary Philip Matyszak

LEGIONARY PHILIP MATYSZAK LEGIONARY The Roman Soldier’s (Unofficial) Manual With 92 illustrations To John Radford, Gunther Maser and the others from 5 Group, Mrewa. Contents Philip Matyszak has a doctorate in Roman history from St John’s College, I Joining the Roman Army 6 Oxford, and is the author of Chronicle of the Roman Republic, The Enemies of Rome, The Sons of Caesar, Ancient Rome on Five Denarii a Day and Ancient Athens on Five Drachmas a Day. He teaches an e-learning course in Ancient II The Prospective Recruit’s History for the Institute of Continuing Education at Cambridge University. Good Legion Guide 16 III Alternative Military Careers 33 HALF-TITLE Legionary’s dagger and sheath. Daggers are used for repairing tent cords, sorting out boot hobnails and general legionary maintenance, and consequently see much more use than a sword. IV Legionary Kit and Equipment 52 TITLE PAGE Trajan addresses troops after battle. A Roman general tries to be near the front lines in a fight so that he can personally comment afterwards on feats of heroism (or shirking). V Training, Discipline and Ranks 78 VI People Who Will Want to Kill You 94 First published in the United Kingdom in 2009 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181a High Holborn, London wc1v 7qx VII Life in Camp 115 First paperback edition published in 2018 Legionary © 2009 and 2018 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London VIII On Campaign 128 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording IX How to Storm a City 149 or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 103 (1994) 223–228

MICHAEL F. PAVKOVIČ SINGULARES LEGATI LEGIONIS: GUARDS OF A LEGIONARY LEGATE OR A PROVINCIAL GOVERNOR? aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 103 (1994) 223–228 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 223 SINGULARES LEGATI LEGIONIS: GUARDS OF A LEGIONARY LEGATE OR A PROVINCIAL GOVERNOR? In a recent article Dr. N.B.Rankov discusses the famous inscription of Ti.Claudius Maximus from the village of Grammeni near Philippi in Macedonia. Rankov pays particular attention to the rank of singularis legati legionis, interpreted by Prof. M.P.Speidel in his commentary as a guardsman of the legionary commander. Rankov is likewise concerned with the implications that can be drawn from the existence of such guards for the legionary legates.1 The substance of Rankov's argument is that mention of singulares legati legionis does not mean that Claudius Maximus was a bodyguard of the legate in his capacity as legionary commander but rather that the legate was at the time serving as a temporary governor for the province of Moesia.2 Rankov's hypothesis rests on two basic assumptions. The first is that there were extraordinary circumstances which caused the legate to be raised temporarily to the rank of governor. He places this unusual situation in the year A.D. 85 when the Dacians invaded the province and killed the consular governor, Oppius Sabinus.3 Rankov then argues that the governor's death meant heavy casualties amongst his guards, the singulares, which in turn necessitated the formation of a new guard unit for the acting governor. Claudius Maximus was chosen for service in the new guard, but the legionary legate was only an ad hoc governor, retaining his rank, and hence Maximus is styled singularis legati legionis.4 This leads us to Rankov's second premise, which concerns those officers with the right to singulares. -

The Roman Army in the Third Century Ad Lukas De Blois My Issue In

INTEGRATION OR DISINTEGRATION? THE ROMAN ARMY IN THE THIRD CENTURY A.D. Lukas de Blois My issue in this paper is: what was the main trend within the Roman military forces in the third century ad? Integration, or disintegration into regional entities? This paper is not about cultural integration of ethnic groups in multicultural parts of the Roman Empire, such as the city of Rome, thriving commercial centres, and border regions to which the armies had brought people from various parts of the Empire, and where multicultural military personnel lived together with indigenous groups, craftsmen from different origins, and immigrants from commercially active regions, either in canabae adjacent to castra stativa, or in garrison towns, as in the Eastern parts of the Empire. In variatio upon an issue raised by Frederick Naerebout in another paper published in this volume, I might ask myself in what sense an army, which in the third century ad was progressively composed of ethnically and culturally different units, kept functioning as an integrated entity, or in actual practice disintegrated into rivalling, particularistic regional forces whose actual or potential competition for money and supplies con- stantly threatened peace and stability in the Empire, particularly in times of dangerous external wars, when the need for supplies increased. The discussion should start with Septimius Severus. After his victories over Pescennius Niger, some tribes in northern Mesopotamia, and Albinus in Gaul, Severus had to replenish the ranks of his armies, for example at the Danube frontiers, which had yielded many men to Severus’ field armies and his new praetorian guard. -

A Reconstruction of the Greek–Roman Repeating Catapult

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca - Università degli studi di Napoli Federico II Mechanism and Machine Theory 45 (2010) 36–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Mechanism and Machine Theory journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mechmt A reconstruction of the Greek–Roman repeating catapult Cesare Rossi *, Flavio Russo Department of Mechanical Engineering for Energetics (DIME), University of Naples ‘‘Federico II”, Via Claudio, 21, 80125 Naples, Italy article info abstract Article history: An ‘‘automatic” repeating weapon used by the Roman army is presented. Firstly a short Received 21 February 2009 description is shown of the working principle of the torsion motor that powered the Received in revised form 17 July 2009 Greek–Roman catapults. This is followed by the description of the reconstructions of these Accepted 29 July 2009 ancient weapons made by those scientists who studied repeating catapults. The authors Available online 4 September 2009 then propose their own reconstruction. The latter differs from the previous ones because it proposes a different working cycle that is almost automatic and much safer for the oper- Keywords: ators. The authors based their reconstruction of the weapon starting from the work of pre- History of Engineering vious scientists and on their own translation of the original text (in ancient Greek) by Ancient automatic weapons Mechanism reconstruction Philon of Byzantium. Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Among the designers of automata and automatic devices in ancient times Heron of Alexandria (10 B.C.–70 A.D.) was probably the best known. -

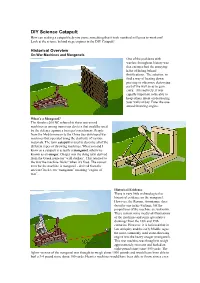

DIY Science Catapult

DIY Science Catapult How can making a catapult help you prove something that it took mankind millennia to work out? Look at the science behind siege engines in the DIY Catapult! Historical Overview On War Machines and Mangonels One of the problems with warfare throughout history was that enemies had the annoying habit of hiding behind fortifications. The solution: to find a way of beating down, piercing or otherwise destroying part of the wall so as to gain entry. Alternatively, it was equally important to be able to keep others intent on destroying your walls at bay. Enter the one- armed throwing engine. What’s a Mangonel? The Greeks c200 BC referred to these one-armed machines as among numerous devices that could be used by the defence against a besieger’s machinery. People from the Mediterranean to the China Sea developed war machines that operated using the elasticity of various materials. The term catapult is used to describe all of the different types of throwing machines. What you and I know as a catapult is actually a mangonel, otherwise known as an onager. Onager was the slang term derived from the Greek name for ‘wild donkey’. This referred to the way the machine ‘kicks’ when it’s fired. The correct term for the machine is mangonel - derived from the ancient Greek term “manganon” meaning “engine of war”. Historical Evidence There is very little archaeological or historical evidence on the mangonel. However, the Roman, Ammianus, does describe one in his writings, but the proportions of the machine are unknown. There remain some medieval illustrations of the machines and some speculative drawings from the 18th and 19th centuries. -

Ad Pirum (Hrušica) in Claustra Alpium Iuliarum

Vestnik XXVI AD PIRUM (HrušicA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Peter Kos Vestnik XXVI AD PIRUM (HrušicA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Peter Kos Ad Pirum (Hrušica) in Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 5 Izdajatelj – partner projekta Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Slovenije Peter Kos: AD PIRUM (HRUŠICA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Vsebina Za izdajatelja: Jelka Pirkovič Uvod 7 Urednica zbirke: Zgodovina raziskovanj 7 Biserka Ribnikar Vasle Urednik: Obrambni sistem Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 13 Peter Kos Redaktor: Umestitev zapornega sistema Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 14 Marko Stokin Recenzija: Arhitektura zapor 15 Janka Istenič Zaporni zidovi 20 Jezikovni pregled: Kamniti oporniki 21 Alenka Kobler Stolpi 22 Oblikovanje: Vratni stolpi 25 Nuit, d. o. o. V zaporne zidove vgrajene manjše trdnjave 26 Naslovnica: Tloris cisterne v sondah XX in XXII (Arhiv AONMS) Trdnjava na Lanišču 26 Trdnjava pod Brstom pri Martinj Hribu 27 Ljubljana, 2014 Kronološka vprašanja gradnje zapornega sistema 32 Funkcija zapornega sistema Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 35 Publikacija je sofinancirana v okviru Programa čezmejnega sodelovanja Slovenija-Italija 2007–2013 iz sred¬stev Evropskega sklada za regionalni razvoj in iz nacionalnih sredstev. Zgodovinski viri 37 Vsebina publikacije ne odraža nujno uradnega stališča Evropske unije. Hrušica 41 Za vsebino publikacije je odgovoren izključno avtor. Hrušica v antičnih virih 41 © ZVKDS in Peter Kos, 2014. Vse pravice pridržane. Trdnjava 42 Brez pisnega dovoljenja založnika in avtorja je prepovedano reproduciranje, distribuiranje, javna priobčitev, -

The Contribution of the Segovia Mint Factory to the History of Manufacturing As an Example of Mass Production in the 16Th Century

applied sciences Article The Contribution of the Segovia Mint Factory to the History of Manufacturing as an Example of Mass Production in the 16th Century Francisco García-Ahumada * and Cristina Gonzalez-Gaya * Department of Construction and Manufacturing Engineering, ETSII-Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), C/Juan del Rosal 12, 28040 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.G.-A.); [email protected] (C.G.-G.); Tel.: +34-629-67-27-37 (C.G.-G.) Received: 1 October 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019; Published: 7 December 2019 Abstract: A new means of minting currency was first used at the Hall Mint in Tyrol in 1567. This new minting process employed a roller instead of a hammer and used hydropower to fuel the laminating and coining mills, as well as ancillary equipment, such as the forge or the lathe. In 1577, Philip II of Spain expressed his interest in the new technology and, after a successful technology transfer negotiation with the County of Tyrol, Juan de Herrera was commissioned to design a factory to accommodate this new minting process. The resulting design seamlessly integrated this new technology. The architectural layout of the factory was derived from the integration of different trades related to the manufacturing workflow, and their effective distribution within a more effective workplace allowed for better use of the hydraulic resources available, and, thus, improvements in the productivity and reliability of the manufacturing process, as well as in the quality of the finished product. Juan de Herrera’s design led to the creation of a ground-breaking manufacturing process, unparalleled in the mint industry in Europe at the time. -

Ancient Technology Honors Seminar III, Inhabiting Other Lives, FIU Honors College (IDH 2003-U01) Fall Semester – 2018

Ancient Technology Honors Seminar III, Inhabiting Other Lives, FIU Honors College (IDH 2003-U01) Fall Semester – 2018 Instructor: Dr. Jill Baker Tuesdays and Thursdays, 11.00 a.m. to 12.15 p.m. Office location: DM 233, (305) 348-4100 Classroom: GC 286 Office hours: By Appointment or Borders Café GC, 10.15-10.45 a.m. Tu/Th email: [email protected] Purpose of the Course: The purpose of this class is to explore ancient technology and engineering. Thanks to archaeological excavation, monumental buildings, gates, city walls, roads, and ships have been discovered. These sometimes-gigantic structures were constructed without the benefit of bull dozers, cranes, lifts, drills, or any of the modern tools with which we are familiar and lived in relative luxury. So, how did the ancient people move materials and build these amazing cities with surprising amenities? This class seeks to elucidate the ingenuity of the ancient mind in order to understand their technology which in turn will help us to better understand our own and apply these, and new, ideas to the future. Questions that will be addressed include what the ancients knew, when and how did they know it; what machines and tools did they use and for what purposes; how does technology and engineering help society advance; how can we apply these principles to our world and to the future? Fall Semester: The big stuff - monumental constructions, residential dwellings, urban planning, etc. Spring Semester: The smaller things – machines, maritime transportation, terrestrial transportation, medicine, time-keeping, etc. This syllabus will be distributed on the first day of class in the spring semester. -

Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal • 2018 Spring

HUNGARIAN ARCHAEOLOGY E-JOURNAL • 2018 SPRING www.hungarianarchaeology.hu PLUMBATA, THE ROMAN-STYLE DARTS. A Late Antique Weapon from Annamatia TAMÁS KESZI1 It is possible to view an unusual object in the display showing Roman military equipment at the permanent exhibit of the Intecisa Museum, a special weapon of the army in Late Antiquity, the plumbata.2 The meaning of the Latin word is ‘leaden’, but if the construction and use of the implement is taken into account it could be called a dart in English. With this ca. 50 cm long, hand-thrown weapon the heavy infantry could have begun to disrupt the diployment of the enemy from a distance. WRITTEN SOURCES The name and description of the projectile weapon called a plumbata in Latin is known from numerous sources from Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. (VERMAAT 2015) (Fig. 1) Fig. 1: Depiction of a plumbata tribolata and mamillata. The lead weight is missing from the latter (Source: http:// rekostwargames.blogspot.hu/2016/11/roman-unit-menapii-seniores.html, date of download: 19 April 2018) According to Flavius Vegetius Renatus, who lived in the Late Imperial period, the expert soldiers of two legions in Illyricum used the plumbata, and so they were called Mattiobarbuli (I 17. II 15. 16. 23. III 14. IV 21. 44.). The emperors Diocletian (284–305) and Maximian (286–305) honored the two units with the title Jovian and Herculean for their prowess. From Vegetius’s description it seems that the two units used the plumbata prior to Diocletian coming to power, but it is perhaps only after this, in the last decades of the 3rd century, that its use spread to the other units of the empire as well. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

History in French Liberal Thought, 1814-1834: the Contribution of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer

CLASS, SLAVERY AND THE INDUSTRIALIST THEORY OF HISTORY IN FRENCH LIBERAL THOUGHT, 1814-1834: THE CONTRIBUTION OF CHARLES COMTE AND CHARLES DUNOYER DAVID MERCER HART KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE MAY 1990 DECLARATION OF LENGTH OF THE DISSERTATION I declare that the length of the dissertation "Class, Slavery and the Industrialist Theory of History in French Liberal Thought, 1814-1834: The Contribution of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer" does not exceed eighty thousand words, excluding footnotes and bibliography. David Mercer Hart Faculty of History King's College, Cambridge Signed: Date: DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration. Signed: Date: ii ABSTRACT The work of Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer spanning the years from 1814 to 1834 demonstrates that a reassessment of the nature of nineteenth century liberalism in general, and early nineteenth century French liberalism in particular, is required. The picture of nineteenth century liberalism which emerges from traditional accounts does not prepare one for the kind of liberalism advocated by Comte and Dunoyer, with their ideas of class analysis, exploitation, the relationship between the mode of production and political culture, and the historical evolution from one mode of production to another through definite stages of economic development. We have been told that liberals restricted themselves to purely political concerns, such as freedom of speech and constitutional government, or economic concerns, such as free trade and deregulation, and eschewed the so-called "social" issues of class and exploitation. I will argue in this thesis that there was a group of liberals in Restoration France which does not fit this traditional view. -

STEM Leads to Rome

All STEM Leads to Rome: Teaching Roman Technology to Middle School Students of Color STEM is all the rage now in pre-collegiate education - STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) has become a buzzword for innovation and career preparation. Schools have added STEM coordinator positions to their faculty, robotics programs to their curricula, and makerspaces to their libraries. Grant money from major industries has poured into schools for classes and after-school programs that teach kids about STEM. Most elementary schools in the US have STEM or STEAM programs built into their curricula or offer after-school programs. Classics can benefit in many ways from a closer alliance with STEM education. Lucky for the field of classics, the Romans (and Greeks) were STEM geniuses. In this paper, I’ll present two full-year, elective curricula of my creation in which middle school students explore the ancient classical world through the lens of STEM. The aim of these curricula is to broaden the scope of classics instruction and draw in students who learn more deeply by doing and making. Without the constructs, and constraints, of language instruction, students learn about the classical world in physical ways. In one course, called Roman Technology, students read ancient Roman texts (in translation) for STEM inspiration and then use experimental archaeology to reproduce the products and processes of the ancient Romans. Each class is a hands-on workshop using real tools, bringing ancient Roman technology to life. Topics covered include common Roman engineering marvels such as concrete, arches, hydraulics, and road construction, but also those which have less obvious STEM connections such as hair styling, writing, and mosaic design.