Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal • 2018 Spring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies at 1st Level: Alchemist Basic weapons, Natural, Crossbows, any other 1 Barbarian Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Bard Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Cavalier Basic weapons, Natural, Spears, any other 3 Cleric Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, any other 2(3 groups if not following a deity) Druid Basic weapons, Natural, druid weapons, any other 1 Fighter Basic weapons, Natural, any other 5 Gunslinger Basic weapons, Natural, firearms, any other 3 Monk Basic weapons, and all monk weapons Inquisitor Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, Bows or Crossbows, any other 3 (4 groups if not following a deity) Magus Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Oracle Basic weapons, Natural, any other 1 (+3 if taking Skill at Arms) Paladin/AntiPaladin Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Ranger Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Rogue Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Sorcerer Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Summoner Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Witch Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Wizard Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows This system doesn’t change Racial Weapon Familiarity. Weapon Group Name: Weapons In Group: Axes bardiche, battleaxe, dwarven waraxe, greataxe, handaxe, heavy pick, hooked axe, knuckle axe, light pick, mattock, orc double axe, pata, and throwing axe Basic club, dagger, quarterstaff, and sling Blades, Heavy bastard sword, chakram, double chicken saber, double -

A Reconstruction of the Greek–Roman Repeating Catapult

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca - Università degli studi di Napoli Federico II Mechanism and Machine Theory 45 (2010) 36–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Mechanism and Machine Theory journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mechmt A reconstruction of the Greek–Roman repeating catapult Cesare Rossi *, Flavio Russo Department of Mechanical Engineering for Energetics (DIME), University of Naples ‘‘Federico II”, Via Claudio, 21, 80125 Naples, Italy article info abstract Article history: An ‘‘automatic” repeating weapon used by the Roman army is presented. Firstly a short Received 21 February 2009 description is shown of the working principle of the torsion motor that powered the Received in revised form 17 July 2009 Greek–Roman catapults. This is followed by the description of the reconstructions of these Accepted 29 July 2009 ancient weapons made by those scientists who studied repeating catapults. The authors Available online 4 September 2009 then propose their own reconstruction. The latter differs from the previous ones because it proposes a different working cycle that is almost automatic and much safer for the oper- Keywords: ators. The authors based their reconstruction of the weapon starting from the work of pre- History of Engineering vious scientists and on their own translation of the original text (in ancient Greek) by Ancient automatic weapons Mechanism reconstruction Philon of Byzantium. Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Among the designers of automata and automatic devices in ancient times Heron of Alexandria (10 B.C.–70 A.D.) was probably the best known. -

DIY Science Catapult

DIY Science Catapult How can making a catapult help you prove something that it took mankind millennia to work out? Look at the science behind siege engines in the DIY Catapult! Historical Overview On War Machines and Mangonels One of the problems with warfare throughout history was that enemies had the annoying habit of hiding behind fortifications. The solution: to find a way of beating down, piercing or otherwise destroying part of the wall so as to gain entry. Alternatively, it was equally important to be able to keep others intent on destroying your walls at bay. Enter the one- armed throwing engine. What’s a Mangonel? The Greeks c200 BC referred to these one-armed machines as among numerous devices that could be used by the defence against a besieger’s machinery. People from the Mediterranean to the China Sea developed war machines that operated using the elasticity of various materials. The term catapult is used to describe all of the different types of throwing machines. What you and I know as a catapult is actually a mangonel, otherwise known as an onager. Onager was the slang term derived from the Greek name for ‘wild donkey’. This referred to the way the machine ‘kicks’ when it’s fired. The correct term for the machine is mangonel - derived from the ancient Greek term “manganon” meaning “engine of war”. Historical Evidence There is very little archaeological or historical evidence on the mangonel. However, the Roman, Ammianus, does describe one in his writings, but the proportions of the machine are unknown. There remain some medieval illustrations of the machines and some speculative drawings from the 18th and 19th centuries. -

Ad Pirum (Hrušica) in Claustra Alpium Iuliarum

Vestnik XXVI AD PIRUM (HrušicA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Peter Kos Vestnik XXVI AD PIRUM (HrušicA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Peter Kos Ad Pirum (Hrušica) in Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 5 Izdajatelj – partner projekta Zavod za varstvo kulturne dediščine Slovenije Peter Kos: AD PIRUM (HRUŠICA) IN CLAUSTRA ALPIUM IULIARUM Vsebina Za izdajatelja: Jelka Pirkovič Uvod 7 Urednica zbirke: Zgodovina raziskovanj 7 Biserka Ribnikar Vasle Urednik: Obrambni sistem Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 13 Peter Kos Redaktor: Umestitev zapornega sistema Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 14 Marko Stokin Recenzija: Arhitektura zapor 15 Janka Istenič Zaporni zidovi 20 Jezikovni pregled: Kamniti oporniki 21 Alenka Kobler Stolpi 22 Oblikovanje: Vratni stolpi 25 Nuit, d. o. o. V zaporne zidove vgrajene manjše trdnjave 26 Naslovnica: Tloris cisterne v sondah XX in XXII (Arhiv AONMS) Trdnjava na Lanišču 26 Trdnjava pod Brstom pri Martinj Hribu 27 Ljubljana, 2014 Kronološka vprašanja gradnje zapornega sistema 32 Funkcija zapornega sistema Claustra Alpium Iuliarum 35 Publikacija je sofinancirana v okviru Programa čezmejnega sodelovanja Slovenija-Italija 2007–2013 iz sred¬stev Evropskega sklada za regionalni razvoj in iz nacionalnih sredstev. Zgodovinski viri 37 Vsebina publikacije ne odraža nujno uradnega stališča Evropske unije. Hrušica 41 Za vsebino publikacije je odgovoren izključno avtor. Hrušica v antičnih virih 41 © ZVKDS in Peter Kos, 2014. Vse pravice pridržane. Trdnjava 42 Brez pisnega dovoljenja založnika in avtorja je prepovedano reproduciranje, distribuiranje, javna priobčitev, -

Inventor Center the Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE

Hands-On in the Inventor Center The Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Complex Spring Catapult, Leonardo daVinci from Leonardo’s Catapults , http://members.iinet.net.au/~rmine/Leonardo.html WHATWHAT’’’’SSSS INSIDE? • Essential Questions • Glossary • Making thethethe Most ofofof Your Visit • Resources • CorrelationCorrelationssss tototo Standards • Activities (Coming Soon) • Facilitation ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS During your facilitated hands-on experience in the Inventor Center: Catapult Forces Challenge , the facilitator will be posing essential questions to your students in two categories: The In- ventive Process and the Science of Catapults and Trebuchets. These questions may also be use- ful for you as a teacher to gain background information as well as for facilitating higher order thinking during class discussions. The Inventive Process Inventor Center encourages students to explore the thrilling process of invention. The Inventor Center includes a series of participatory stations: build, experiment, learn and share. Students will define the problem, build a prototype, experiment with the prototype, learn how well the prototype works (solves the problem), and share their ideas or inventions with others. Who is an inventor? An inventor is someone who uses technology in a new way to solve a problem. An invention is a unique or novel device, method, or process. Inventions are different than discoveries because a discovery is detecting something that already ex- ists. In the Inventor Center everyone is an inventor. What is the inventive process? There are many ways to invent. Most inventive processes consist of four main parts: learning, building, testing (or exper- imenting), and sharing. These four parts of the inventive process can happen in any order. -

Catapult to the Front of the Line

Name: Date: Catapult to the Front of the Line GOAL Create a catapult that will hurl a penny through a target from the furthest distance away. MATERIALS TIME TO CREATE r!,rP!vlDu4! Acr,turY Read the following, hightighting important information, and answer the questions. lmagine that you are in the midst of a snowball fight. ln addition to preparing for battle, you also need to think about protection. Hiding behind something is helpfu[, but what if your enemy is able to break down your barrier? Throughout history, finding a way to destroy the enemy's protection while maintaining a safe distance was cha[[enging-untilthe invention of the catapult, the one-armed throwing machine. Ancient Greeks referred to the catapult as a mangone[, meaning "engine of war." The mangonel, weighing approximately z tons, functioned by ftinging heavy objects over and through walls. Because of its powerful kicking motion, mangonels were also referred to as onagers, a name derived from onagros, meaning "wild donkey." A ballista was another type of catapult. lt was designed similarty to the crossbow. Ballistas relied on the work of torsion to release ammunition that looked like giant arrows. Over time, gravity catapults, such as the trebuchet, were invented. Trebuchets were designed to hur[ a heavy object into a high arc, which was quite useful for breaking down castle walls, especially if the ammunition involved fire. Catapults have been one of the most effective weapons for warfare. A sling is attached to the end of the catapult's arm. ln lowering the arm, the user stores energy in the ropes, and when the arm is released, the arm is flung forward. -

The Book of the Crossbow Free

FREE THE BOOK OF THE CROSSBOW PDF Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey | 400 pages | 26 Mar 2009 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486287201 | English | New York, United States Crossbow by Dayle Campbell Gaetz Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about The Book of the Crossbow problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Crossbow by Dayle Campbell Gaetz. Fourteen-year-old Matt has only one goal in life: to become a hermit. He has no use for school, but he loves the solitude of the forest. When he hikes up to the cabin he built for The Book of the Crossbow, he discovers a mysterious stranger named Forrest has moved in. At first Matt doesn't connect Forrest's appearance with the rash of local robberies. Forrest seems to be the perfect hermit Fourteen-year-old Matt has only one goal in life: to become a hermit. Forrest seems to be the perfect hermit, and he teaches Matt the skills he needs to achieve his goal, including how to hunt with a crossbow. But when Forrest tries to kill an endangered Roosevelt elk, Matt questions the ethics of his new friend. When Matt discovers a stolen rifle in his cabin, he finds himself trapped in a dangerous situation. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

The Xanten-Wardt and Carlisle Catapult Finds

The Xanten-Wardt Roman torsion catapult and catapult parts from Carlisle Alan Wilkins The Xanten-Wardt frame from a Roman torsion bolt-shooting catapult of the 1st century AD was discovered in 1999 in a gravel quarry in north west Germany at 51˚ 40ˈ N, 6˚ 27ˈ E. The site was once an arm of the Rhine, but is now the Südsee, a water-sport lake NNE of the Xanten Archaeological Park. The sumptuous official report on the find has now been published by Verlag Philipp von Zabern as Xanten Berichte Band 18: Die Frühkaiserzeitliche Manuballista Aus Xanten-Wardt. This exciting discovery has added far more to our understanding of these machines than previous finds of catapult frame parts from Ampurias, Caminreal and elsewhere. Not only has the metal plating survived, but for the first time the wood of the frame and the front end of the slider and stock have been preserved. The iron and bronze plating includes the battle shields for the spring-cord, organic material from which has been identified by electron microscope as sinew rope. The four bronze washers and washer-bars are there, with one complete washer pin and two broken ones. Fig. 1 The Xanten-Wardt frame after conservation (Maarten Dolmans) Most of the Xanten-Wardt report is rightly devoted to the details of the long and painstaking recovery of the machine from its coffin of solidified sand, grit and pebbles. X- rays and CT scans were used to locate the buried parts, in order to guide the delicate task of removing the concretion. -

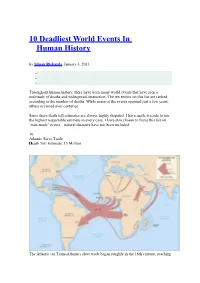

10 Deadliest World Events in Human History by Simon Rickards, January 3, 2013

10 Deadliest World Events In Human History by Simon Rickards, January 3, 2013 • • • Throughout human history, there have been many world events that have seen a multitude of deaths and widespread destruction. The ten entries on this list are ranked according to the number of deaths. While some of the events spanned just a few years, others occurred over centuries. Since these death toll estimates are always highly disputed, I have made it a rule to use the highest respectable estimate in every case. I have also chosen to focus this list on ‘man-made’ events – natural disasters have not been included. 10 Atlantic Slave Trade DeathD Toll Estimate: 15 Million The Atlantic (or Trans-Atlantic) slave trade began roughly in the 16th century, reaching its peak in the 17th century until finally being all but abolished in the 19th Century. The main driving force behind this trade was the need for European empires to establish themselves in the New World. European and American settlers therefore began to use mainly West African slaves to fill the vast labor needs on plantations. Estimates vary on the amount of slaves who died, but it is said that for every ten slaves taken on a ship, fourf would perish from causes related to mistreatment. 9 Late Yuan Warfare & Transition to Ming Dynasty DeathD Toll Estimate: 30 Million The Yuan dynasty was founded by Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, around 1260. Yuan literally translates as ‘Great is the Heavenly and Primal’, though there proved to be nothing either great or heavenly about it. -

Michael Foran (Order #10809442) Everyman Unchained: Fighters

Michael Foran (Order #10809442) Everyman Unchained: Fighters Authors: Alexander Augunas Cover Artist: Jacob Blackmon Cover Design: Alexander Augunas Interior Art: Jacob Blackmon Editor: Luis Loza DESIGNATION OF PRODUCT IDENTITY All company names, logos, and artwork, images, graphics, illustrations, trade dress, and graphic design elements and proper names are designated as Product Identity. Any rules, mechanics, illustrations, or other items previously designated as Open Game Content elsewhere or which are in the public domain are not included in this declaration DECLARATION OF OPEN GAME CONTENT All content not designated as Product Identity is declared Open Game Content as de- scribed in Section 1(d) of the Open Game License Version 1.0a. Compatibility with the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME requires the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME from Paizo Inc.. See http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG for more information on the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Paizo Inc. does not guarantee compatibility, and does not endorse this product. Pathfinder is a registered trademark of Paizo Inc., and the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME and the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility Logo are trademarks of Paizo Inc., and are used under the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility License. See http:// paizo.com/pathfinderRPG/compatibility for more information on the compatibility li- cense. Everyman Unchained: Fighters © 2016 by Everyman Gaming, LLC. ABOUT EVERYMAN GAMING, LLC Everyman Gaming began as the blog of Alexander Augunas in January 2014, where he wrote about Pathfinder Roleplaying Game tips, tricks, and techniques for both players and GMs. In May of 2014, Alex began talks with the Know Direction Network about bringing his blog to their site under the name Guidance. -

Roman Warfare and Fortification

Roman Warfare and Fortification Oxford Handbooks Online Roman Warfare and Fortification Gwyn Davies The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World Edited by John Peter Oleson Print Publication Date: Dec 2009 Subject: Classical Studies, Ancient Roman History, Material Culture Studies Online Publication Date: Sep 2012 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734856.013.0028 Abstract and Keywords This article concentrates on the role of technology in improving the operational capabilities of the Roman state. It reviews the organizational and weapon system developments that enabled Roman armies to engage their enemies with confidence in the field, alongside the evolution of fortification schemes that enabled economies of force, which were essential to imperial security. Roman weapons and equipment include the spear, sword, missiles, artillery, shields, helmets, and body armor. Although the Roman army was often on the attack and made use of complex siege technology, it was also highly skilled in the preparation of defensive fortifications. The Romans diligently applied themselves to the arts of war. Their successful mastery of battlefield techniques and their adoption, where appropriate, of equipment and technologies first introduced by their opponents allowed Roman armies to sustain the state over several hundreds of years of challenge and change. Keywords: Roman armies, Roman warfare, Roman fortification, spear, sword, missiles, artillery, shields, helmets, body armor Warfare and the Romans A message relayed to the Roman people by Romulus after his translation to the heavens, stands as an unambiguous endorsement of Roman military prowess. “Tell the Romans that it is the gods' will that my Rome shall be the capital of the world; therefore let them cultivate the arts of war and let them know and teach their children that no human force can resist Roman arms” (Livy 1.16.7). -

Barbarian Invasion

The Representation of the Roman Army c.363-425AD in Rome: Total War: Barbarian Invasion Daniel McDevitt Senior Sophister Trinity College Dublin Word Count: 11,539 McDevitt i Acknowledgments An enormous thank you to Dr. Hazel Dodge for all her help with this paper, for not laughing too much when I suggested the idea of analyzing a video game, and for her speedy and timely responses to my many frantic emails. A thank you to my mom and grandmom for encouraging me to pursue my education and supporting me in my moving to a foreign country for university. A thank you to my muse who inspires me to be a better person and has supported me in my many moments of selfdoubt. And finally a thank you to my father for always giving me the motivation to succeed. McDevitt ii Table of Contents Abbreviations………………………………………………………….pg iii Introduction…………………………………………………………….pg 1 Chapter 1: Military Unit Types and Titles …………………….…....pg 4 Chapter 2: Army Recruitment, Training, and Upkeep………….. pg 21 Chapter 3: Arms and Armor ……………………………………….pg 36 Conclusion………………………………………………………….. pg 49 Appendix ………………………………………………………….... pg 51 Bibliography……………………………………………………...…. pg 65 McDevitt iii Abbreviations Amm. Ammianus Marcellinus Barbarian Invasion Rome: Total War: Barbarian Invasion C.Th. C odex Theodosianus Not. Dig. N otitia Dignitatum Veg. Vegetius Zos. Zosimus McDevitt 1 Introduction The working objective of this dissertation is to examine the manner in which the video game R ome: Total War: Barbarian Invasion represents the realities of the Roman army between 363 and 425 AD. Before getting into format and layout, a few notes first on the relevance of the objective of this paper, the time period under study, and the video game itself.