The Mandaeans and the Question of Their Origin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semitic Languages

ARAMAIC 61 of the Dead Sea. Although the ninth-century B.C. Moabite inscriptions present the earliest "Hebrew" characters of the alphabetic script, their language cannot be regarded as an Hebrew dialect. f) Edomite 7.9. Edomite, attested by a few inscriptions and seals dated from the 9th through the 4th century B.C., was the Canaanite idiom of southern Transjordan and eastern Negev. Despite our very poor knowledge of the language, palaeography and morphology reveal some specifically Edomite features. B. Aramaic 7.10. Aramaic forms a widespread linguistic group that could be clas sified also as North or East Semitic. Its earliest written attestations go back to the 9th century B.C. and some of its dialects survive until the present day. Several historical stages and contemporaneous dialects have to be distinguished. a) Early Aramaic 7.11. Early Aramaic is represented by an increasing number of inscrip tions from Syria, Assyria, North Israel, and northern Transjordan dating from the 9th through the 7th century B.C. (Fig. 11). There are no impor tant differences in the script and the spelling of the various documents, except for the Tell Fekherye statue and the Tell Halaf pedestal inscrip tion. The morphological variations point instead to the existence of several dialects that represent different levels of the evolution of the language. While the Tell Fekherye inscription (ca. 850 B.C.) seems to testify to the use of internal or "broken" plurals, the two Samalian inscriptions from Zincirli (8th century B.C.) apparently retain the case endings in the plural and have no emphatic state. -

Kiraz 2019 a Functional Approach to Garshunography

Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 7 (2019) 264–277 brill.com/ihiw A Functional Approach to Garshunography A Case Study of Syro-X and X-Syriac Writing Systems George A. Kiraz Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton and Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute, Piscataway [email protected] Abstract It is argued here that functionalism lies at the heart of garshunographic writing systems (where one language is written in a script that is sociolinguistically associated with another language). Giving historical accounts of such systems that began as early as the eighth century, it will be demonstrated that garshunographic systems grew organ- ically because of necessity and that they offered a certain degree of simplicity rather than complexity.While the paper discusses mostly Syriac-based systems, its arguments can probably be expanded to other garshunographic systems. Keywords Garshuni – garshunography – allography – writing systems It has long been suggested that cultural identity may have been the cause for the emergence of Garshuni systems. (In the strictest sense of the term, ‘Garshuni’ refers to Arabic texts written in the Syriac script but the term’s semantics were drastically extended to other systems, sometimes ones that have little to do with Syriac—for which see below.) This paper argues for an alterna- tive origin, one that is rooted in functional theory. At its most fundamental level, Garshuni—as a system—is nothing but a tool and as such it ought to be understood with respect to the function it performs. To achieve this, one must take into consideration the social contexts—plural, as there are many—under which each Garshuni system appeared. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

(RSEP) Request October 16, 2017 Registry Operator INFIBEAM INCORPORATION LIMITED 9Th Floor

Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) Request October 16, 2017 Registry Operator INFIBEAM INCORPORATION LIMITED 9th Floor, A-Wing Gopal Palace, NehruNagar Ahmedabad, Gujarat 380015 Request Details Case Number: 00874461 This service request should be used to submit a Registry Services Evaluation Policy (RSEP) request. An RSEP is required to add, modify or remove Registry Services for a TLD. More information about the process is available at https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/rsep-2014- 02-19-en Complete the information requested below. All answers marked with a red asterisk are required. Click the Save button to save your work and click the Submit button to submit to ICANN. PROPOSED SERVICE 1. Name of Proposed Service Removal of IDN Languages for .OOO 2. Technical description of Proposed Service. If additional information needs to be considered, attach one PDF file Infibeam Incorporation Limited (“infibeam”) the Registry Operator for the .OOO TLD, intends to change its Registry Service Provider for the .OOO TLD to CentralNic Limited. Accordingly, Infibeam seeks to remove the following IDN languages from Exhibit A of the .OOO New gTLD Registry Agreement: - Armenian script - Avestan script - Azerbaijani language - Balinese script - Bamum script - Batak script - Belarusian language - Bengali script - Bopomofo script - Brahmi script - Buginese script - Buhid script - Bulgarian language - Canadian Aboriginal script - Carian script - Cham script - Cherokee script - Coptic script - Croatian language - Cuneiform script - Devanagari script -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Kitle İletişim Araçları Eğitim İlişkisi

Manden El Yazısının Kökeni 211 ARAMÎ DİLLERİN KADÎM İRAN BETİKLERİNE BAĞLI KÖKLERİ: MANDEN EL YAZISININ KÖKENİ Charles G. Häberl Çev.: Mehmet Sait TOPRAK ÖZET Günümüz Ortadoğu‟sunda bulunan herhangi bir başka el yazısına benzemeyen Irak ve İran‟daki Mandenlerce hâlâ kullanılan yegâne bitişik elyazısı, Mandenler‟in yazılı edebiyatının sırlı ve gizli kökenlerini aydınlatmada ve belir- gin bir şekilde farklı dinsel bir gelenek olarak ortaya çıkışlarına dair bir ipucu sağlayabilir. Mandenlerin bugün bulundukları bölgelerdeki antik elyazıları ile karşılaştırıldığında, Manden el yazısının, Partlılar döneminin son zamanlarının (ve son derece belirgin bir tarzda M.S. II. yüzyılın) bir ürünü olduğu, Anado- lu‟dan ve kuzeydeki Kafkasya‟ya, oradan güneydeki Mesene (Characene)‟ye ve Elam‟a yayılan bir grup el yazısıyla çok yakın benzerliklere sahip olduğu anlaşı- lır. Ki bu el yazılarının tamamının ya bunlardan türediği ya da büyük ölçüde Part devri resmi el yazısının tesirinde kaldığı görülür. Mandenler‟in son dönem Arsaklılar‟la bağlantısı, onların kendi söylenceleri ve metinsel gelenekleriyle teyid edilmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Aramca, Partça, Manden el yazısı, ABSTRACT Iranian Scripts for Aramaic Languages: The Origin of the Mandaic Script The unique cursive script still employed by the Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, which is unlike any other script found in the modern Middle East, may provide a clue to the obscure origins of their written literature and their emergence as a distinct religious tradition. Comparison with ancient scripts from the regions where the Mandaeans are found today indicates that the Mandaic script is a product of the late Parthian period (and more specifically the second century C.E.) and has its closest affinities with a group of scripts ranging from Anatolia and the Caucasus in the north to Characene and Elymais in the south, all of which appear to derive from or to be heavily influenced by the Parthian chancery script.The association of the Mandaeans with the later Arsacids is corroborated by their own legends and their textual tradition. -

331 Doc. Type: Input to ISO/IEC 10646:2003 Title

INCITS/L2/08- 331 Doc. Type: Input to ISO/IEC 10646:2003 Title: Proposed additions to ISO/IEC 10646:2003 Source: US National Body Project: JTC1 02.18 Status: For review by WG2 Date: 2008-08-15 Distribution: WG2 This document describes additions to ISO/IEC 10646:2003 that the US National body would like to see integrated in the standard. The items in this category are considered mature enough for inclusion in a future amendment. 1. Mandaic The U.S. requests the addition of the Mandaic script of 29 characters with glyphs and codepoint positions as proposed by document WG2 N3485 (L2/08-270R), including just one punctuation mark with new name 085E MANDAIC PUNCTUATION but without 085F KASHIDA and 085D MANDAIC SMALL PUNCTUATION. Mandaic will be located in a new Mandaic block from 0840-085F. 2. Malayalam The U.S. requests the addition of two Malayalam characters,0D29 MALAYALAM LETTER NNNA and U+0D3A MALAYALAM LETTER TTTA as documented in N3494. 3. Cyrillic Supplement The U.S. requests the addition of four Cyrillic characters: 0524 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER PE WITH DESCENDER, 0525 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE WITH DESCENDER as documented in N3435R and 0526 CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER SHHA WITH DESCENDER, and 0527 CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHHA WITH DESCENDER as documented in N3481. 4. Arabic Pedagogical Symbols The U.S. requests the addition of 16 Arabic characters as documented in N3460R: 0880 ARABIC SINGLE NUQTA ABOVE 0881 ARABIC SINGLE NUQTA BELOW 0882 ARABIC DOUBLE NUQTA ABOVE 0883 ARABIC DOUBLE NUQTA BELOW 0884 ARABIC TRIPLE NUQTA ABOVE 0885 ARABIC TRIPLE NUQTA BELOW 0886 ARABIC TRIPLE INVERTED NUQTA ABOVE 0887 ARABIC TRIPLE INVERTED NUQTA BELOW 0888 ARABIC QUADRUPLE NUQTA ABOVE 0889 ARABIC QUADRUPLE NUQTA BELOW 088B ARABIC DOUBLE DANDA BELOW 088C ARABIC DOUBLE NUQTA VERTICAL ABOVE 088D ARABIC DOUBLE NUQTA VERTICAL BELOW 0893 ARABIC SINGLE CIRCLE BELOW 0894 ARABIC TOTA ABOVE 0895 ARABIC TOTA BELOW 1 5. -

Amendment for .Mls

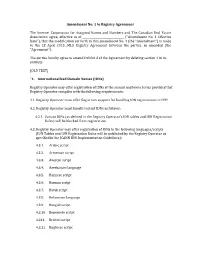

Amendment No. 1 to Registry Agreement The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and The Canadian Real Estate Association agree, effective as of _______________________________ (“Amendment No. 1 Effective Date”), that the modification set forth in this amendment No. 1 (the “Amendment”) is made to the 23 April 2015 .MLS Registry Agreement between the parties, as amended (the “Agreement”). The parties hereby agree to amend Exhibit A of the Agreement by deleting section 4 in its entirety: [OLD TEXT] “4. Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs) Registry Operator may offer registration of IDNs at the second and lower levels provided that Registry Operator complies with the following requirements: 4.1. Registry Operator must offer Registrars support for handling IDN registrations in EPP. 4.2. Registry Operator must handle variant IDNs as follows: 4.2.1. Variant IDNs (as defined in the Registry Operator’s IDN tables and IDN Registration Rules) will be blocked from registration. 4.3. Registry Operator may offer registration of IDNs in the following languages/scripts (IDN Tables and IDN Registration Rules will be published by the Registry Operator as specified in the ICANN IDN Implementation Guidelines): 4.3.1. Arabic script 4.3.2. Armenian script 4.3.3. Avestan script 4.3.4. Azerbaijani language 4.3.5. Balinese script 4.3.6. Bamum script 4.3.7. Batak script 4.3.8. Belarusian language 4.3.9. Bengali script 4.3.10. Bopomofo script 4.311. Brahmi script 4.3.12. Buginese script 4.3.13. Buhid script 4.3.14. Bulgarian language 4.3.15. -

Comparative Lexical Studies in Neo-Mandaic Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics

Comparative Lexical Studies in Neo-Mandaic Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics Editorial board Aaron D. Rubin and C.H.M. Versteegh VOLUME 73 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ssl Comparative Lexical Studies in Neo-Mandaic By Hezy Mutzafi LEIDEN • bOSTON 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mutzafi, Hezy. Comparative lexical studies in Neo-Mandaic / By Hezy Mutzafi. pages cm. — (Studies in semitic languages and linguistics ; Volume 73) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25704-7 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25705-4 (e-book) 1. Mandaean language—Grammar. 2. Mandaean language—Lexicology. I. Title. PJ5329.M88 2014 492’.3—dc23 2013048037 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 0081-8461 ISBN 978-90-04-25704-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25705-4 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Unicode Reference Lists: Other Script Sources

Other Script Sources File last updated October 2020 General ALA-LC Romanization Tables: Transliteration Schemes for Non-Roman Scripts, Approved by the Library of Congress and the American Library Association. Tables compiled and edited by Randall K. Barry. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1997. ISBN 0-8444-0940-5. Adlam Barry, Ibrahima Ishagha. 2006. Hè’lma wallifandè fin èkkitago’l bèbèrè Pular: Guide pra- tique pour apprendre l’alphabet Pulaar. Conakry, 2006. Ahom Barua, Bimala Kanta, and N.N. Deodhari Phukan. Ahom Lexicons, Based on Original Tai Manuscripts. Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, 1964. Hazarika, Nagen, ed. Lik Tai K hwam Tai (Tai letters and Tai words). Souvenir of the 8th Annual conference of Ban Ok Pup Lik Mioung Tai. Eastern Tai Literary Association, 1990. Kar, Babul. Tai Ahom Alphabet Book. Sepon, Assam: Tai Literature Associate, 2005. Alchemical Symbols Berthelot, Marcelin. Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs. 3 vols. Paris: G. Steinheil, 1888. Berthelot, Marcelin. La chimie au moyen âge. 3 vols. Osnabrück: O. Zeller, 1967. Lüdy-Tenger, Fritz. Alchemistische und chemische Zeichen. Würzburg: JAL-reprint, 1973. Schneider, Wolfgang. Lexikon alchemistisch-pharmazeutischer Symbole. Weinheim/Berg- str.: Verlag Chemie, 1962. Anatolian Hieroglyphs Hawkins, John David, and Halet Çambel. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Ber- lin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2000. ISBN 3-11-010864-X. Herbordt, Suzanne. Die Prinzen- und Beamtensiegel der hethitischen Grossreichszeit auf Tonbullen aus dem Ni!antepe-Archiv in Hattusa. Mit Kommentaren zu den Siegelin- schriften und Hieroglyphen von J. David Hawkins. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2005. ISBN: 3-8053-3311-0. -

Writing Vowels in Punic: from Morphography to Phonography

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Writing vowels in Punic: from morphography to phonography Robert Crellin University of Cambridge ABSTRACT This paper traces the employment of original Phoenician-Punic guttural graphemes, <ˀ>, <ˁ>, <h>, and <ḥ>, to represent vowel phonemes in later Punic. Three typologically distinct treatments are identified: 1) morphographic, where the grapheme <ˀ> indicates the etymological glottal stop /ˀ/ (its original function) as well as vowel morphemes without specifying their phonological character; 2) morpho-phonographic, where guttural graphemes continue to indicate etymological guttural consonants, but now both the presence of a vowel morpheme and (potentially) the vowel quality of that morpheme; and 3) phonographic, where the same set of guttural graphemes serve to denote vowel phonemes only, and do not any longer indicate guttural consonants. The threefold division is argued for on the basis of the Late Punic language written in Punic and Neopunic scripts. Despite the availability of dedicated vowel graphemes, these are not obligatorily written in any period of written Punic. It is suggested that a typologically significant path of development may be observed across these three uses of guttural graphemes, with 3) the endpoint of a development from morphography to phonography. Keywords: orthography; Phoenician-Punic; Neopunic; gutturals; script; morphography; phonography; abjad; alphabet 1. Introduction The Punic language was written for a large part of its history using a script descended from the West-Semitic scripts of the Near East of the late second and early first millennium BCE (Lehmann 2012: 14–16). It was adopted for writing both Semitic and non-Semitic languages, notably Greek. -

N3505 Date: 2008-10-15 Updated

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3505 Date: 2008-10-15 Updated Updated Agenda – Meeting # 53 Topic (Document No.) Proposed Outcome 1. Opening and roll call (N3451) Update WG2Distribution List 2. Approval of the agenda (N3505) Approved agenda 3. Approval of minutes of meeting 52 (N3453) Approved Minutes 4. Review action items from meeting 52 (N3453-AI) Updated Action Item List 5. JTC1 and ITTF matters: FYI 5.1. Amendment 4 Publication – 2008-07-01 5.2. Amendment 5 Status – FDAM – Deadline 2008-11-05 6. SC2 matters: FYI 6.1. SC2 Program of Work 6.2. Submittals to ITTF – FDAM Amendment 5 6.3. Ballot results – Amendment 6.2 (N3515) 6.4. SC2 Business Plan (SC2 N4035) 7. WG2 matters: 7.1. Roadmap (N3518) FYI 7.2. WD for next 10646 edition Review (N3508, N3509, N3510) 7.3. Multi-column charts (N3408) 7.4. Handling CJK compatibility characters with variation sequences (N3525) 8. IRG status and reports: 8.1. Include 5 unencoded HKSCS characters Review and progress (N3513, N3513-A) 8.2. Summary Report IRG30 (N3512) FYI 8.3. IRG 30 Resolutions (N3511) FYI 8.4. Fonts availability (N3524) 8.5. 9. Script Contributions related to current ballot (6.2): Review 9.1. Nushu (N3449, N3462, N3463, N3497). 9.2. Meetei Mayek 9.2.1. Proposed encoding for Meetei Mayek (N3473) 9.2.2. Proposed encoding for Meetei Mayek Extended Block (N3478) 9.3. Vedic – Proposal and background 9.3.1. Proposal to encode additional characters for Vedic (N3488) 9.3.2. Devanagari examples of Vedic tone Yajurvedic Mid–char Svarita (N3493) 9.4.