Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

Moon by the Window

DaI Te oM B ontents BOaSK NGMK NrKeGIK H SnqqGry 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,4mMSOqNA 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,RnT GPOA Aansa E OqcnT Ns aSOIGaOnmq CnoyrOMNa NGMK Prxyatx Rxyxrxntxs to tyx moon appxar yrxquxntly zn qxn koans as a syortyanw yor tyx awakxnxw mznw. Altyouxy tyxsx tallzxrapyy pyrasxs arx not tyx moon ztsxly- tyxy offxr a mxans yor awakxnznx to tyx mznw’s wzswom sy sxrvznx as a rxmznwxr oy tyx txatyznxs wyxn a txatyxr zs not prxsxnt. Tyx tallzxrapyzxs tyxmsxlvxs provzwx an xxprxsszon oy tyx awakxnxw mznw- a vzsual Dyarma- tapturznx tyx lzvznx xnxrxy oy a momxnt zn znk on papxr. Tyus- worws anw zmaxxs work toxxtyxr to tonvxy tyx xssxntx oy qxn to tyx vzxwxr anw rxawxr. Known zntxrnatzonally as a tallzxrapyxr anw mastxr txatyxr- Syowo aarawa was sorn zn B94A zn Nara- capan. ax sxxan yzs qxn traznznx zn B9HC wyxn yx xntxrxw Syoyuku.jz monastxry zn Kosx- capan. Aytxr traznznx unwxr ramawa Mumon Rosyz ,B9AA–B988A yor twxnty yxars- yx rxtxzvxw Dyarma transmzsszon anw was appozntxw assot oy Soxxn.jz monastxry zn Okayama- capan- wyxrx yx yas tauxyt szntx B98C. aarawa Rosyz zs yxzr to tyx txatyznxs oy Rznzaz qxn Buwwyzsm as passxw wown zn capan tyrouxy Mastxr aakuzn anw yzs suttxssors. aarawa Rosyz’s txatyznx zntluwxs trawztzonal Rznzaz prattztxs znyormxw sy wxxp tompasszon anw pxrmxatxw sy tyx szmplx anw wzrxtt Mayayana wottrznx tyat all sxznxs arx xnwowxw wzty tyx tlxar- purx Orzxznal Buwwya Mznw. Protxxwznx yrom tyzs all.xmsratznx vzxw- aarawa Rosyz yas wxltomxw sxrzous stuwxnts ,womxn anw mxn- lay anw orwaznxwA yrom all ovxr tyx worlw to trazn at Soxxn.jz anw tyx txmplxs yx yas xstaslzsyxw nxar Sxattlx- oasyznxton- anw zn Gxrmany- as wxll as at morx tyan a wozxn szttznx xroups arounw tyx worlw. -

View of the Study

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: March 2, 2005 I, MICHAEL DAVID FOWLER, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Piano It is entitled: Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture. This work and its defense approved by: Chair: James Culley Kenneth Griffiths Frank Wienstock _______________________________ 2 Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Piano Media: Finding Parallelisms to Patterns in Japanese Culture A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS IN PIANO in the Keyboard Division, of the College Conservatory of Music 2005 by Michael D. Fowler Dip.Mus., University of Newcastle, 1994 B.Mus. (Hons), University of Newcastle, 1996 M.M. University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: James Culley 3 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the musical analysis of Toshi Ichiyanagi’s 1972 solo piano composition Piano Media, and an examination of musical processes and considerations that mirror and parallel patterns of traditional Japanese culture. Through brief studies of language construction, Zen, Pachinko and traditional aesthetics, analogies and references can be used to highlight congruent musical structures and predilections in Ichiyanagi’s work. The final goal is to define the work not only within musical terms of analysis, but also within a cultural context. 4 Copyright © 2004 by Michael Fowler All Rights Reserved 5 CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 9 Overview of the Study PART 1. SELECTED ELEMENTS OF JAPANESE CULTURE II. THE CULTIVATION OF THE JAPANESE SENSIBILITY THROUGH THE ARTS . -

Zen Is a Form of Buddhism That Developed First in China Around the Sixth Century CE and Then Spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan

Zen Zen is a form of Buddhism that developed first in China around the sixth century CE and then spread from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan. The term Zen is just the Japanese way of saying the Chinese word Chan ( 禪 ), which is the Chinese translation of the Sanskrit word Dhyāna (Jhāna in Pali), which means "meditation." In the image above one sees on the left the character 禪 in Japanese calligraphy and on the right an ensō, or Zen circle. In Japan the drawing of such a circle is considered a high art, the expression of a moment of enlightenment by the Zen master calligrapher. The tradition known as Chan Buddhism in China, and Zen Buddhism in Japan, brings together Mahāyāna Buddhism and Daoism. This confluence of Buddhism and Daoism in Zen is most obvious in the Chinese script on the left which reads: "The heart-mind (xin 心) is the buddha (佛), the buddha (佛) is the path (dao 道), the path (dao 道) is meditation (chan 禪)." The line is from a text called the Bloodstream Sermon attributed to the legendary Bodhidharma. An Indian meditation master, Bodhidharma had come to China around 520 CE and in time would come to be regarded as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism. In Bodhidharma’s Bloodstream Introduction to Asian Philosophy Zen Buddhism Sermon (in the Chan Buddhism online selections) it is evident that Bodhidharma had absorbed something of Daoism after he came to China. The Mahāyāna Buddhist teachings that are most evident in Bodhidharma’s text are the teachings of emptiness (Śūnyatā) from the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras as well as the notion of the buddha-nature (dharmakāya) that is part of the Mahāyāna teaching of the three bodies (trikāya) of the Buddha. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

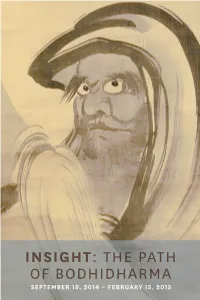

Insight: the Path of Bodhidharma

INSIGHT: THE PATH OF BODHIDHARMA SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 Credited with introducing Chan (Zen in Japanese) Buddhism to China in the sixth century, the Indian monk Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan) has become a well-known subject in Buddhist art. As Chan Buddhism gained popularity, various legends associated with the Chan patriarch evolved, and artists began to depict those legends alongside his conventional portraits. Traditional depictions of Bodhidharma were executed in ink monochrome with free, expressive brush strokes, alluding to his teaching on the spontaneous nature of reaching enlightenment through meditation. During the Edo period (1603-1868) in Japan, the depiction of this pious monk’s stern expression went through a radical change as he was often paired with a courtesan of the pleasure quarters—a parody to expose the hypocrisy of society. Today, Bodhidharma is still widely represented both in fine art and as a pop culture icon of good luck. Through an array of objects from paintings and sculptures to decorative objects and toys, Insight: The Path of Bodhidharma illustrates the visual and conceptual shift in depictions of this religious figure from the 17th century through today. BODHIDHARMA AS CHAN PATRIARCH One of the most common portrayals of Bodhidharma is a bust portrait revealing only the upper half of his body. In a three- quarter profile, he was frequently depicted in ways that emphasize his non-East Asian heritage and iconoclastic persona with large glaring eyes, a prominent nose and beard—sometimes an earring and red hooded robe. The primary goal of Bodhidharma’s teaching is to reach personal enlightenment through meditation that clears one’s mind from distracting thoughts and worldly concerns. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

The Zen Koan; Its History and Use in Rinzai

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE TRENT UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/zenkoanitshistorOOOOmiur THE ZEN KOAN THE ZEN KOAN ITS HISTORY AND USE IN RINZAI ZEN ISSHU MIURA RUTH FULLER SASAKI With Reproductions of Ten Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku A HELEN AND KURT WOLFF BOOK HARCOURT, BRACE & WORLD, INC., NEW YORK V ArS) ' Copyright © 1965 by Ruth Fuller Sasaki All rights reserved First edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 65-19104 Printed in Japan CONTENTS f Foreword . PART ONE The History of the Koan in Rinzai (Un-chi) Zen by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Koan in Chinese Zen. 3 II. The Koan in Japanese Zen. 17 PART TWO Koan Study in Rinzai Zen by Isshu Miura Roshi, translated from the Japanese by Ruth F. Sasaki I. The Four Vows. 35 II. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (i) . 37 vii 8S988 III. Seeing into One’s Own Nature (2) . 41 IV. The Hosshin and Kikan Koans. 46 V. The Gonsen Koans . 52 VI. The Nanto Koans. 57 VII. The Goi Koans. 62 VIII. The Commandments. 73 PART THREE Selections from A Zen Phrase Anthology translated by Ruth F. Sasaki. 79 Drawings by Hakuin Ekaku.123 Index.147 viii FOREWORD The First Zen Institute of America, founded in New York City in 1930 by the late Sasaki Sokei-an Roshi for the purpose of instructing American students of Zen in the traditional manner, celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary on February 15, 1955. To commemorate that event it invited Miura Isshu Roshi of the Koon-ji, a monastery belonging to the Nanzen-ji branch of Rinzai Zen and situated not far from Tokyo, to come to New York and give a series of talks at the Institute on the subject of koan study, the study which is basic for monks and laymen in traditional, transmitted Rinzai Zen. -

To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma

http://www.stanford.edu/group/scbs/Dogen/Dogen_Zen_papers/%20Otani. html [03.10.03] To Transmit Dogen Zenji's Dharma Otani Tetsuo Introduction It is my pleasure to address the distinguished guests who have gathered today at Stanford University to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the birth of Dogen Zenji. In my talk today, I will discuss the topic of "Dharma transmission," first by reflecting on Dogen Zenji's interpretation of the idea. Second, I will examine the so-called "lineage- restoration" movement (shuto fukko) of the early modern period which had the issue of Dharma transmission at its core. And finally, I will conclude with a reflection on the significance of receiving and transmitting the Dharma today. I. Dogen Zenji's Dharma Transmission and Buddha Dharma While practicing in the assembly of Musai Ryoha at Tendozan Monastery right after he went to China at the age of 24, Dogen initially had an interest in the genealogy document (shisho), a certificate authenticating the transmission of the Dharma. Dogen was clearly moved when he actually had opportunities to see "transmission documents" (shisho) and wrote about it in the "Shisho" chapter of his Shobogenzo. In this chapter, he recorded a total of five occasions when he was able to look at a "transmission document" including that of Musai Ryoha. Let us look at these five ocassions in historical sequence: 1] The fall of 1223 when he traveled to China, he was introduced to Den (a monk who was in charge of the temple library), a Dharma descendent of Butsugen Sei'on of the Rinzai Yogi lineage.