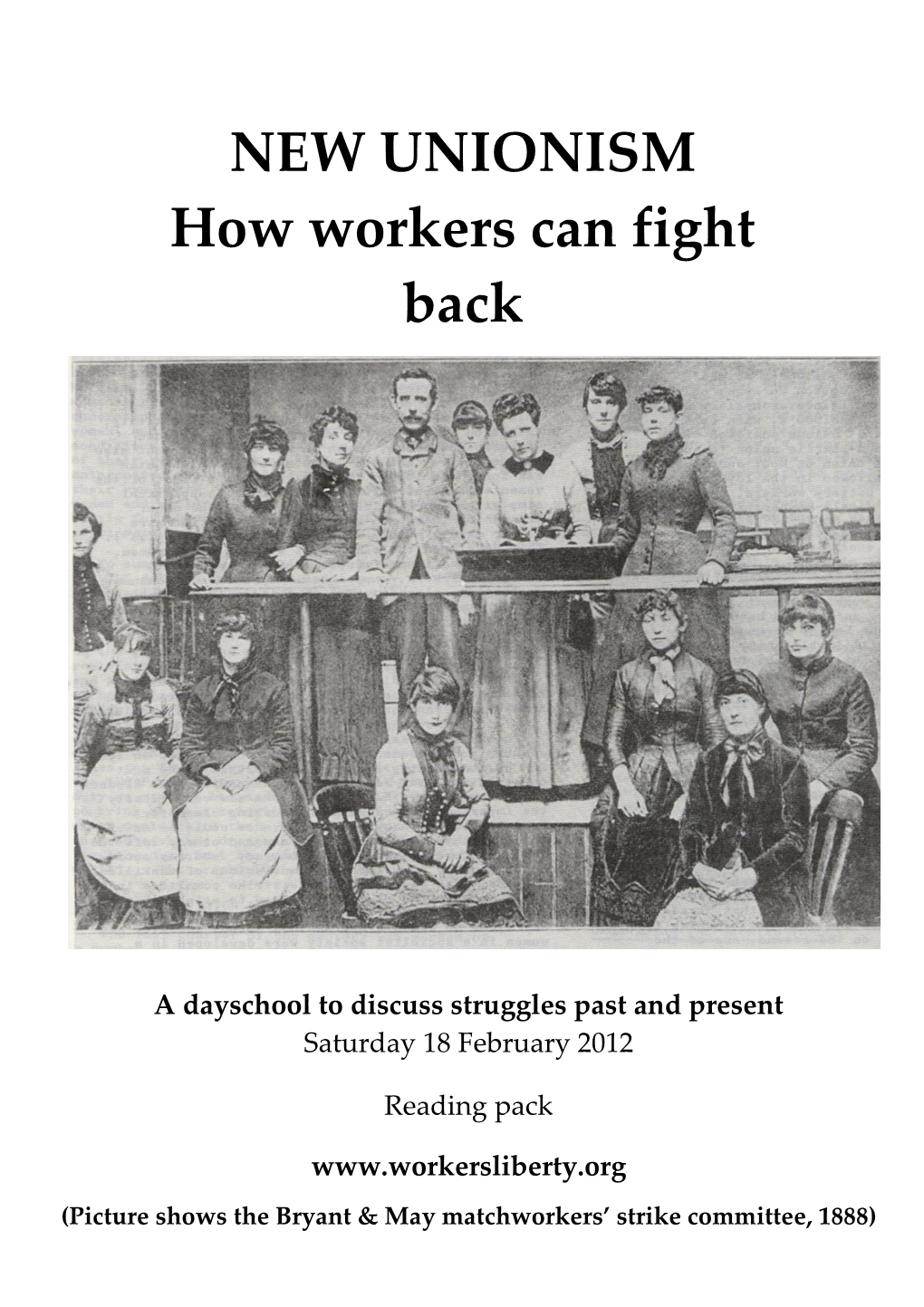

NEW UNIONISM How Workers Can Fight Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organising Workers' in Italy and Greece

Organising workers’ counter-power in Italy and Greece Lorenzo Zamponi and Markos Vogiatzoglou Trade unions in Southern European’s austerity-ridden countries have been considerably weakened by the last six years of crisis. Labour’s loss of power in countries such as Greece and Italy is significant. First of all, the tri-partite systems of collective bargaining (state, employers, unions) that characterised the 1990s and early 2000s in both countries collapsed. Neither state nor employers have shown any concrete willingness to re-establish some sort of collective bargaining mechanisms. Governments in austerity-ridden countries do not seem to need unions anymore.1 Secondly, despite their vocal opposition, trade unions have failed to block austerity measures, as well as other detrimental changes in labour legislation. The period 2008-2014 has been characterised by limited worker mobilisation in Italy and by the failure of the numerous protests and general strikes in Greece to deliver any concrete achievements. Worse, union members express deep mistrust of their own leader- ship, as does the broader population.2 This bleak landscape does not give the whole picture of labour movement activity in those countries, however. In both cases, interesting labour-related projects are being developed to restore a workers’ counter-power, both by unionists and social movement activists who are exploring actions outside of the traditional trade union repertoire. They draw from concepts such as ‘social movement unionism’,3 social 1 State of Power 2015 Organising workers’ counter-power in Italy and Greece Lorenzo Zamponi and Markos Vogiatzoglou unionism4 or ‘radical political unionism’,5 which will be detailed below. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abbott, S., 1973. Employee Participation. Old Queen Street Papers. Conservative Central Office. Aglietta, Michel, 1998. Capitalism at the Turn of the Century: Regulation Theory and the Challenge of Social Change. New Left Review I/232. Altman, M., 2002. Economic Theory and the Challenge of Innovative Work Practices. Economic and Industrial Democracy. 23, 271. Bain, G.S., 1983. Industrial Relations in Britain. Blackwell, Oxford, UK. Bassett, P., 1986. Strike Free: New Industrial Relations in Britain. Palgrave Macmillan, London. BIM, 1975. Employee Participation: A Management View. London, British Institute of Management. Cadbury, A., 1978. Prospects for Codetermination in the United Kingdom. Chief Executive Magazine. 20–21. Cairncross, S.A., 1992. The British Economy since 1945: Economic Policy and Performance, 1945–1990. Blackwell, Oxford, UK and Cambridge, Mass., USA. CBI, 1966. Evidence to the Royal Commission on Trades Unions and Employers’ Associations. Confederation of British Industry, London. CBI, 1968. Productivity Bargaining. Confederation of British Industry, London. CBI, 1979. Pay: The Choice Ahead. Confederation of British Industry, London. CBI, 1980. Trade Unions in a Changing World: The Challenge for Management. Confederation of British Industry, London. DOI: 10.1057/9781137413819.0009 Bibliography CBI, 1986. Vision 2010. Confederation of British Industry, London. CPS, 1975. Why Britain Needs a Social Market Economy. London, Centre for Policy Studies. Chiplin, B., Coyne, J. and Sirc, L., 1975. Can Workers Manage? Institute of Economic Affairs. City Company Law Committee, 1975. Employee Participation. Coates, K. and Topham, T., 1974. The New Unionism. Penguin, Harmondsworth. Conservative Party, 1965. Putting Britain Right Ahead: A Statement of Conservative Aims. Conservative and Unionist Central Office, London. -

The Theological Socialism of the Labour Church

‘SO PECULIARLY ITS OWN’ THE THEOLOGICAL SOCIALISM OF THE LABOUR CHURCH by NEIL WHARRIER JOHNSON A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis argues that the most distinctive feature of the Labour Church was Theological Socialism. For its founder, John Trevor, Theological Socialism was the literal Religion of Socialism, a post-Christian prophecy announcing the dawn of a new utopian era explained in terms of the Kingdom of God on earth; for members of the Labour Church, who are referred to throughout the thesis as Theological Socialists, Theological Socialism was an inclusive message about God working through the Labour movement. By focussing on Theological Socialism the thesis challenges the historiography and reappraises the significance of the Labour -

People, Place and Party:: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911

Durham E-Theses People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911 Young, David Murray How to cite: Young, David Murray (2003) People, place and party:: the social democratic federation 1884-1911, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk People, Place and Party: the Social Democratic Federation 1884-1911 David Murray Young A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of Politics August 2003 CONTENTS page Abstract ii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1- SDF Membership in London 16 Chapter 2 -London -

Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements

<Abstract> Revitalization Strategy of Labor Movements Korea Labour & Society Institute 1. The stagnation of trade union movement is an international phenomenon. The acceleration of globalization and technological innovation, the expanding predominance of service industries in the economies of advanced industrialised countries and the concomitant shifts in the composition of employment, and the deepening of neoliberal policy climate in the context of economic slow-down, which have prevailed since the 1980s, have all contributed to the stagnation of trade union movement in most countries across the world. This phenomenon has been captured through such indicators as the decline in union density, the weakening of political and social influence, and decentralisation of collective bargaining have been, among others. The trade union movements in different countries have, however, since 1990s, developed and undertaken a variety of "revitalisation"strategies to wake out of the stagnation. The specific shape of the revitalisation strategy were informed by the specific nature of the challenge the unions faced, the characteristics of the industrial relations system in which the unions were constituted, and the historical identity individual trade union movement espoused. However, organising efforts, internal innovation, social partnership, strengthening of political campaign activities, and extension of solidarity with civil society and community networks have featured as common components in most of the varied strategies. The evidence of these common initiatives points to the existence of some common challenge that courses through the country-specific situations the trade union movements in different countries have found themselves in. This study examines the strategic responses of the trade unions in the selected countries have undertaken in the face of the challenges faced by the international labour movement. -

Transformations of Trade Unionism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Knotter, Ad Book — Published Version Transformations of trade unionism: Comparative and transnational perspectives on workers organizing in Europe and the United States, eighteenth to twenty-first centuries Work Around the Globe: Historical Comparisons and Connections Provided in Cooperation with: Amsterdam University Press (AUP) Suggested Citation: Knotter, Ad (2018) : Transformations of trade unionism: Comparative and transnational perspectives on workers organizing in Europe and the United States, eighteenth to twenty-first centuries, Work Around the Globe: Historical Comparisons and Connections, ISBN 978-90-485-4448-6, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, http://dx.doi.org/10.5117/9789463724715 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193995 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Alternative International Labour Communication by Computer After Two Decades1

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Labour communications Volume 2 (2): 241 - 269 (November 2010) Waterman, Alternative labour communication Alternative International Labour Communication by Computer After Two Decades1 Peter Waterman Will offline social movement organisations be willing to cede control as ordinary people increasingly leverage social networking tools to channel their own activities? The destruction of hierarchies online means that top-down organisations will face increasing pressure from members to permit more rank- and-file debate and input. This is a healthy process and a long time in coming. If traditional organisations are to embrace the dynamism of the social networking sphere and move beyond simply posting op-eds on Huffington Post [a US website - PW] written by union presidents or NGO executive directors, they will have to cede significant control. Organisations that resist this trend will become increasingly irrelevant, online and offline. (Brecher, Costello2 and Smith, 2009) Rather than having more representatives or improving representation, rather even than having a form of direct democracy where ‘the people’ get to vote for many more purposes than merely electing leaders, the alterglobalisation movement suggests a form of democracy that rejects all formal and fixed representation… Through decentralisation and connectivity, decisions that affect an entire network of people can, in principle, be discussed at every node of that network and then decided through communication between nodes. This communication is carried out by people who act as very temporary ‘representatives’…who have no decision- making power, but transmit the necessary information to make a collective decision – even a global one – in all the affected local contexts. -

Colonial Forms of Labour Organisation in Nineteenth Century Australia Ray Markey University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Business - Economics Working Papers Faculty of Business 1997 Colonial forms of labour organisation in nineteenth century Australia Ray Markey University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Markey, Ray, Colonial forms of labour organisation in nineteenth century Australia, Department of Economics, University of Wollongong, Working Paper 97-6, 1997, 36. http://ro.uow.edu.au/commwkpapers/257 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] University of Wollongong DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES 1997 COLONIAL FORMS OF LABOUR ORGANISATION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY AUSTRALIA Ray Markey COLONIAL FORMS OF LABOUR ORGANISATION IN NINETEENTH CENTURY A u s t r a l ia Ray Markey Department of Economics University of Wollongong Coordinated by Associate Professors C. Harvie & M.M. Metwally Working Paper Production & Administration: Robert Hood Department of Economics, University of Wollongong Northfields Avenue, Wollongong NSW 2522 Australia Department of Economics University of Wollongong Working Paper Series WP 97-6 ISSN 1321-9774 ISBN 0 86418 510 3 ABSTRACT Australian unionism built upon strong foundations transported from Britain. Subsequently it grew beyond this base in scope and form. By 1890 the level of unionisation of the colonial workforce exceeded that in the mother country. This was mainly due to the upsurge of new unionism in the late 1880s. Although there were many parallels with the new unionism of Britain, the colonial variant was more extensive, preceded the British version and demonstrated its distinctive characteristics, such as a national level of bureaucracy, earlier. -

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I–XV

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I–XV ABBOTTS, William (1873–1930) I ALLEN, Sir Thomas William (1864–1943) I ABLETT, Noah (1883–1935) III ALLINSON, John (1812/13–1872) II ABRAHAM, William (Mabon) (1842–1922) I ALLSOP, Thomas (1795–1880) VIII ACLAND, Alice Sophia (1849–1935) I AMMON, Charles (Charlie) George (1st ACLAND, Sir Arthur Herbert Dyke (1847– Baron Ammon of Camberwell) (1873– 1926) I 1960) I ADAIR, John (1872–1950) II ANCRUM, James (1899–1946) XIV ADAMS, David (1871–1943) IV ANDERSON, Frank (1889–1959) I ADAMS, Francis William Lauderdale (1862– ANDERSON, William Crawford (1877–1919) 1893) V II ADAMS, John Jackson (1st Baron Adams of ANDREWS Elizabeth (1882–1960) XI Ennerdale) (1890–1960) I APPLEGARTH, Robert (1834–1924) II ADAMS, Mary Jane Bridges (1855–1939) VI ARCH, Joseph (1826–1919) I ADAMS, William Edwin (1832–1906) VII ARMSTRONG, William John (1870–1950) V ADAMS, William Thomas (1884–1949) I ARNOLD, Alice (1881–1955) IV ADAMSON, Janet (Jennie) Laurel (1882– ARNOLD, Thomas George (1866–1944) I 1962) IV ARNOTT, John (1871–1942) X ADAMSON, William (1863–1936) VII ASHTON, Thomas (1841–1919) VII ADAMSON, William (Billy) Murdoch (1881– ASHTON, Thomas (1844–1927) I 1945) V ASHTON, William (1806–1877) III ADDERLEY, The Hon. James Granville ASHWORTH, Samuel (1825–1871) I (1861–1942) IX ASKEW, Francies (1855–1940) III AINLEY, Theodore (Ted) (1903–1968) X ASPINWALL, Thomas (1846–1901) I AITCHISON, Craigie (Lord Aitchison) ARTHUR James (1791–1877) XV (1882–1941) XII ATKINSON, Hinley (1891–1977) VI AITKEN, William (1814?–1969) X AUCOTT, -

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I-IX

Consolidated List of Names Volumes I-IX ABBOTTS, William (1873-1930) I ANDERSON, William Crawford (1877- ABLETT, Noah (1883-1935) III 1919) II ABRAHAM, William (Mabon) (1842-1922) APPLEGARTH, Robert (1834-1924) II I ARCH, Joseph (1826--1919) I ACLAND, Alice Sophia (1849-1935) I ARMSTRONG, William John (1870-1950) ACLAND, Sir Arthur Herbert Dyke (1847- V 1926) I ARNOLD, Alice (1881-1955) IV ADAIR, John (1872-1950) II ARNOLD, Thomas George (1866--1944) I ADAMS, David (1871-1943) IV ASHTON, Thomas (1841-1919) VII ADAMS, Francis William Lauderdale (1862- ASHTON, Thomas (1844-1927) I 93) V ASHTON, William (1806--77) III ADAMS, John Jackson (1st Baron Adams ASHWORTH, Samuel (1825-71) I of Ennerdale (1890-1960) I ASKEW, Francis (1855-1940) III ADAMS, Mary Jane Bridges (1855-1939) ASPINW ALL, Thomas (1846--1901) I VI ATKINSON, Hinley (1891-1977) VI ADAMS, William Edwin (1832-1906) VII AUCOTT, William (1830-1915) II ADAMS, William Thomas (1884-1949) I AYLES, Walter Henry (1879-1953) V ADAMSON, Janet (Jennie) Laurel (1882- 1962) IV BACHARACH, Alfred Louis (1891-1966) IX ADAMSON, William (1863-1936) VII BAILEY, Sir John (Jack) (1898-1969) II ADAMSON, William (Billy) Murdoch BAILEY, William (1851-96) II (1881-1945) V BALFOUR, William Campbell (1919-73) V ADDERLEY, The Hon. James Granville BALLARD, William (1858-1928) I (1861-1942) IX BAMFORD, Samuel (1846--98) I ALDEN, Sir Percy (1865-1944) III BARBER, Jonathan (1800-59) IV ALDERSON, Lilian (1885-1976) V BARBER, [Mark] Revis (1895-\965) V ALEXANDER, Albert Victor (1st Earl Al- BARBER, Walter (1864-1930) -

I Took You in the Same Direction Gurney and I Went the Other Day, Through the Same Wood, Along the Leaf-Carpeted Track (Beech Leaves Mainly

Chapter 7: Famous People: In the first of Lionel’s letters in the wartime collection – he makes references to no less than three of his personal acquaintances who made their mark on him and history. All are representative of the left wing and revolutionary liberal intelligencia of the late Victorian and early 20th Century period. I liked to have the account of your busy day. You certainly manage to get a lot in. So you have finished the EC book. Thank you for the few extracts. With regards to Grayson, it was I who introduced him to Carpenter. Didn’t I ever tell you about my friendship with him. I found him at the Hamilton Road Mission in Liverpool when I went and we soon became very friendly, though he was quite ready (before he knew me) to pull me to pieces ! We used to have great discussions at the Debating Society, and he was in my Sunday class of elder scholars. At that time he was just commencing to prepare for the Unitarian Ministry and I coached him in Latin and Greek. At the same time he was doing a lot of public speaking for the Socialists. He never went to M.C.O, (Manchester College Oxford) but for one session, I think, to the H.M.C. (Harris Manchester College) and then gave up the idea. The only time after my leaving Liverpool that I saw much of him was when I proposed his name to Tchertkoff as a companion and kind of tutor to T’s son Dina. -

1889 and All That: New Views on the New Unionism*

DEREK MATTHEWS 1889 AND ALL THAT: NEW VIEWS ON THE NEW UNIONISM* SUMMARY: This article reviews the existing literature on the rise of the New Unionism and suggests some revisions of the nature of the phenomenon based on recent research. One finding is that as institutions the unions were not militant but from their inception favoured a moderate stance regarding relations with employ- ers. The causes of the New Unionism and the strike wave of 1889-1890 are analysed within a framework of neoclassical economics and the major operator in the situation is identified as the dwindling supply of rural labour which increased the value and bargaining power of the unskilled toward the end of the nineteenth century. The year 1889 ranks in the pantheon of British labour history alongside 1834 or 1926. Eric Hobsbawm has called it a year of explosive militancy when the working-class movement took a sharp turn to the left. It "marks a qualitative transformation of the British labour movement and its industrial relations" when "[a] new era of labour relations and class conflict was clearly opening".1 The year is always associated with the rise of the New Unionism, a term used at the time although it has now been debunked so often there might seem to be very little left of the concept. The Webbs, of course, initiated the academic historiography and there has been much subsequent revision. The purpose of this article, however, is to show, first, how the true nature of the New Unionism has still not been properly appreciated. Secondly, in analysing the causes of the rise of the New Unionism and the strike wave that accompanied it - within a model relying heavily on neoclassical economic theory - it will be suggested that hitherto a fundamental operator on industrial relations in the period has been ig- nored.