Image Is Everything: Satiric Elements in Horace's Lyric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caesars and Misopogon: a Linguistic Approach of Flavius Claudius Julianus’ Political Satires

The Buckingham Journal of Language and Linguistics 2015 Volume 8 pp 107-120 CAESARS AND MISOPOGON: A LINGUISTIC APPROACH OF FLAVIUS CLAUDIUS JULIANUS’ POLITICAL SATIRES. Georgios Alexandropoulos [email protected] ABSTRACT This study examines the linguistic practice of two political satires1 (Misopogon or Beard - Hater and Caesars) written by Flavius Claudius Julian2 the Emperor. Its purpose is to describe the way that Julian organizes the coherence and intertextuality of his texts and to draw conclusions about the text, the context of the satires and Julian’s political character. 1. INTRODUCTION Misopogon or Beard - Hater3, is a satirical essay and Julian’s reply to the people of Antioch who satirized him in anapestic verses and neglected his way of political thinking. The political ideology he represented was repelled by the Syrian populace and the corrupt officials of Antioch. Caesars is a Julian’s satire, in which all the emperors reveal the principles of their character and policy before the gods and then they choose the winner. Julian writes Caesars in an attempt to criticize the emperors of the past (mainly Constantine) whose worth, both as a Christian and as an emperor, Julian severely questions. He writes Misopogon when he decides to begin his campaign against the Persians. When he tried to revive the cult relative to ancient divine source of Castalia at the temple of Apollo in the suburb of Daphne, the priests mentioned that the relics of the Christian martyr Babylas prevented the appearance of God. Then Julian committed the great error to order the removal of the remains of the altar and thus they were accompanied by a large procession of faithful Christians. -

John Harbison's Songs for Baritone: a Performer's Guide

John Harbison‘s Songs for Baritone: A Performer‘s Guide A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Peter C. Keates B.M.A., University of Oklahoma, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, CCM, 2006 Abstract This document is a performance guide for Words from Paterson and Flashes and Illuminations, John Harbison‘s song cycles for baritone. It confronts the issues of text interpretation and musical style one must address in order to give the most informed performance of these songs. It provides a synthesis of information about the poems and readings of the poetry Harbison set to music, offers insight into Harbison‘s interpretations of the text, and demonstrates how Harbison‘s atonal style and unique compositional techniques provide a successful musical setting for the chosen texts. The guide also discusses performance issues based on personal experience as well as the experience of the composer and other performers. The poetic style of William Carlos Williams, Michael Fried, Czeslaw Milosz, Elizabeth Bishop, and Eugenio Montale are examined. A transcription of an interview with John Harbison is also included. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 I. Paterson ............................................................................................................................................... -

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1

Teaching Classical Languages Volume 10, Issue 2 Kopestonsky 71 Never Out of Style: Teaching Latin Love Poetry with Pop Music1 Theodora B. Kopestonsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT Students often struggle to interpret Latin poetry. To combat the confusion, teachers can turn to a modern parallel (pop music) to assist their students in understanding ancient verse. Pop music is very familiar to most students, and they already trans- late its meaning unconsciously. Building upon what students already know, teach- ers can reframe their approach to poetry in a way that is more effective. This essay shows how to present the concept of meter (dactylic hexameter and elegy) and scansion using contemporary pop music, considers the notion of the constructed persona utilizing a modern musician, Taylor Swift, and then addresses the pattern of the love affair in Latin poetry and Taylor Swift’s music. To illustrate this ap- proach to connecting ancient poetry with modern music, the lyrics and music video from one song, Taylor Swift’s Blank Space (2014), are analyzed and compared to poems by Catullus. Finally, this essay offers instructions on how to create an as- signment employing pop music as a tool to teach poetry — a comparative analysis between a modern song and Latin poetry in the original or in translation. KEY WORDS Latin poetry, pedagogy, popular music, music videos, song lyrics, Taylor Swift INTRODUCTION When I assign Roman poetry to my classes at a large research university, I re- ceive a decidedly unenthusiastic response. For many students, their experience with poetry of any sort, let alone ancient Latin verse, has been fraught with frustration, apprehension, and confusion. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires Thesis Advisor: Dr. William Wycislo Spring 2004 Acknowledgments My sincerest thanks go to Dr. Wycislo, without whose time and effort this project would have never have happened. Abstract Juvenal was a satirist who has made his mark on our literature and vernacular ever since his works first gained prominence (Kimball 6). His use of allusion and epic references gave his satires a timeless quality. His satires were more than just social commentary; they were passionate pleas to better his society. Juvenal claimed to give the uncensored truth about the evils that surrounded him (Highet 157). He argued that virtue and vice were replacing one another in the Roman Empire. In order to gain better understanding of his claim, in the following paper, I looked into his moral origins as well as his arguments on virtue and vice before drawing conclusions based on Juvenal, his outlook on society, and his solutions. Before we can understand how Juvenal chose to praise or condemn individuals and circumstances, we need to understand his moral origins. Much of Juvenal's beliefs come from writings on early Rome and long held Roman traditions. I focused on the writings of Livy, Cicero, and Polybius as well as the importance of concepts such as pietas andjides. I also examined the different philosophies that influenced Juvenal. The bulk of the paper deals with virtue and vice replacing one another. This trend is present in three areas: interpersonal relationships, Roman cultural trends, and religious issues. First, Juvenal insisted that a focus on wealth, extravagance, and luxury dissolved the common bonds between citizens (Courtney 231). -

Teaching Guide

Teaching guide: Area of study 2 (Popular music) Study piece Little Shop of Horrors (1982) off-Broadway version – the following three tracks: • Prologue/Little Shop of Horrors (overture) • Mushnik and Son • Feed Me. Please note we are unable to reproduce sections of the score and the song lyrics due to copyright restrictions. Contextual information Little Shop of Horrors first appeared as a low budget film in 1960: The story involves a plant which feeds on human blood and tissue. The main characters include: • Mushnik – the owner of the florist shop, who treats his staff badly • Seymour and Audrey – florist shop assistants • Orin – Audrey’s abusive dentist boyfriend • Chiffon, Crystal and Ronnette – a trio of street urchins who comment on the action as the story progresses • Audrey II – the plant. The version on which this guide is written for is the off-Broadway 1982 production. An off-Broadway production is one in a professional theatre venue in New York City with a seated audience capacity between 100 and 499, inclusive. These theatres are smaller than Broadway theatres, but larger than ‘off-off’ Broadway theatres, which seat fewer than 100: Some shows that premiere off-Broadway are subsequently produced on Broadway. A Broadway production takes place in a professional theatre with a seated audience capacity of more than 500 seats. After the 1982 production, there have been subsequent productions worldwide of Little Shop of Horrors and the musical was also made into a 1986 film, directed by Frank Oz. The music for this 1982 off-Broadway production of Little Shop of Horrors was composed by Alan Menken (b.1949). -

Burial Customs and the Pollution of Death in Ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS and the POLLUTION of DEATH in ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES and PARADOXES

Burial customs and the pollution of death in ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS AND THE POLLUTION OF DEATH IN ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES AND PARADOXES ABSTRACT The Roman attitude towards the dead in the period spanning the end of the Republic and the high point of the Empire was determined mainly by religious views on the (im)mortality of the soul and the concept of the “pollution of death”. Contamina- tion through contact with the dead was thought to affect interpersonal relationships, interfere with official duties and prevent contact with the gods. However, considera- tions of hygiene relating to possible physical contamination also played a role. In this study the traditions relating to the correct preparation of the body and the sub- sequent funerary procedures leading up to inhumation or incineration are reviewed and the influence of social status is considered. Obvious paradoxes in the Roman at- titude towards the dead are discussed, e.g. the contrast between the respect for the recently departed on the one hand, and the condoning of brutal executions and public blood sports on the other. These paradoxes can largely be explained as reflecting the very practical policies of legislators and priests for whom considerations of hygiene were a higher priority than cultural/religious views. 1. INTRODUCTION The Roman approach to disposing of the dead in the Republican era and the early Empire (the period from approximately 250 BC to AD 250) was determined in part by diverse cultural/religious beliefs in respect of the continued existence of the soul after death and the con- cept of the “pollution of death”. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

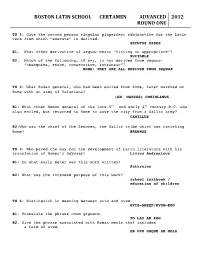

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave". -

A Mixed Place: the Pastoral Symposium of Horace, Odes 1.17

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2018 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 2-2018 A Mixed Place: The aP storal Symposium of Horace Kristen Ehrhardt John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018 Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Ehrhardt, Kristen, "A Mixed Place: The asP toral Symposium of Horace" (2018). 2018 Faculty Bibliography. 14. https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2018 Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Mixed Place: The Pastoral Symposium of Horace, Odes 1.17 Kristen Ehrhardt ABSTRACT: When Horace invites Tyndaris to an outdoor drinking party in Odes 1.17, he mixes the locus amoenus of pastoral with the trappings of symposia. I argue that the mixture of the two poetic spaces creates a potentially volatile combination by muddling the expectations of each place’s safety and danger. I read 1.17 in light of other pastoral poems in Odes 1 to establish Horace’s creation of safe places through the negation of natural perils. Although pastoral has its own dangers, the addition of sympotic motifs in 1.17 attracts different beasts—sexual predators—to Tyndaris’ party. A central conceit of Horace’s pastoral poems is the preternatural safety of their speakers: despite whatever dangers might lurk in the natural realm, the speaker himself remains unharmed.