Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

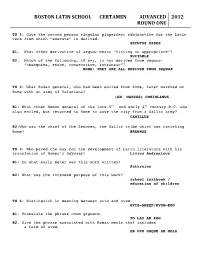

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

A STUDY of SOCIAL LIFE in the SATIRES of JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., the University of British Columbia, 1959. A

A STUDY OF SOCIAL LIFE IN THE SATIRES OF JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1959. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission*. Department of Glassies The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada Date April 28, 196U ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is not to deal with the literary merit and poetic technique of the satirist. I am not asking whether Juvenal was a good poet or not; instead, I intend to undertake this study strictly from a social and historical point of view. From our author's barrage of bitter protests on the follies and foibles of his age I shall try to uncover as much of the truth as possible (a) from what Juvenal himself says, (b) from what his contemporaries say of the same society, and (c) from the verdict of modern authorities. -

Summary of Horace's Satires

Horace Satires Summary of Horace’s Satires Book One 1 The need to find contentment with one’s lot, and the need to acquire the right habits of living in a state of carefree simplicity rather than being a lonely sad miser. 2 The need to practise safe sex: i.e. sex with women who are available and with whom one can have carefree relations. Adultery is a foolish game as (a) one cannot inspect the women before ‘buying’ and (b) it brings huge risks to health and reputation both in the fear of discovery and in being discovered and punished. Epicurean ethics of ‘the little that is enough’ means that whatever is available as a sexual outlet is preferable to pining with love for the unattainable. 3 The need to be indulgent to the faults of our friends if we want them to be indulgent towards us. The poet gives a quick version of Epicurean anthropology to explain the origins of morality and to discount the rigidity of Stoic ethics. 4 Horace’s first literary manifesto. He discusses Lucilius’ outspoken frankness and says that his poems are not really poetry at all but ‘closer to everyday speech.’ His choice of subject-matter is motivated not by malice but by a gentle desire to help others with the sort of good advice which his father had given him. 5 The journey to Brundisium. Horace went with Maecenas and other influential men (including Virgil) to conduct diplomatic discussions with Mark Antony in Spring 37BC. The poem avoids any overt political comment and focusses instead on the details of the journey and the accommodation ‘enjoyed’ or not. -

The Six Books of Lucretius' De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2010 The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Farrell, J. (2010). The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence. Dictynna, 5 Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence Abstract Lucretius’ De rerum natura is one of the relatively few corpora of Greek and Roman literature that is structured in six books. It is distinguished as well by features that encourage readers to understand it both as a sequence of two groups of three books (1+2+3, 4+5+6) and also as three successive pairs of books (1+2, 3+4, 5+6). This paper argues that the former organizations scheme derives from the structure of Ennius’ Annales and the latter from Callimachus’ book of Hynms. It further argues that this Lucretius’ union of these two six-element schemes influenced the structure employed by Ovid in the Fasti. An appendix endorses Zetzel’s idea that the six-book structure of Cicero’s De re publica marks that work as well as a response to Lucretius’ poem. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 The Six Books of Lucretius’ De rerum natura: Antecedents and Influence 2 Joseph Farrell The Six Books of Lucretius’ De rerum natura: Antecedents and Influence 1 The structure of Lucretius’ De rerum natura is generally considered one of the poem’s better- understood aspects. -

Lucretius, Seneca and Persius 1.1-2

Transactions of the American Philological Association 129 (1999) 281-299 Lucretius, Seneca and Persius 1.1-2 Joshua D. Sosin Duke University The second line of Persius' first satire, according to the Commentum Corn uti, was borrowed from the first book of Lucilius' Satires.! Most scholars have balked at this claim, and posit a host of textual corruptions: the commentator really meant Persius 1.1, or Lucretius, or Lucilius book 10. Solutions have been sought in the text of the Commentum, but not in the poem ofPersius. The author of the Commentum initiated this debate with a question: what is the allusive background to Persius 1.2? In answering the same question I offer here a simpler account of what Persius and the author of the Commentum are trying to show at 1.2. The commentary on 1.2, 'quis leget haec?' min tu istud ais? nemo hercule. 'nemo?', states: QUIS LEGET HAEC hunc versum de Lucili primo transtulit. et bene vitae vitia increpans ab admiratione incipit. The poet borrowed this verse from the first book of Lucilius. And he starts off with amazement, railing eloquently against the vices oflife. The chatty dialogue in 1.2 has seemed too prosaic for Lucilius' pen. An error has therefore been postulated so that the more poetic 1.1, instead of 1.2, could be assigned to Lucilius:2 !The Commentum is a ninth-century composition/compilation of a body of scholia, the earliest strata of which seem to have originated ca. 400 C.E. See Robathan et aI. 20 I col. ii; see also foremost Zetze11981: 19-31; Wessner 1917: 473-80, 496-502; Clausen 1956: xiv xv. -

Latin Titles - Sorted by Author

Middlebury College Classics Department Library Catalog: Latin Titles - Sorted by Author Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date Remnants Of Early Selected And Explained F. D. Allen Latin 1889 Hardcover 106 Latin For The Use Of Students Loeb Classical Library, John Arthur Metamorphoses I Apuleius Latin/English 04/01/1990 Hardcover 390 No. 44 Hanson Loeb Classical Library, John Arthur Metamorphoses II Apuleius Latin/English 03/01/1990 Hardcover 384 No. 453 Hanson Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Tomus Primus Latin 1932 Hardcover 768 Book I Aquinas Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Tomus Tertius Latin 1932 Hardcover 690 Book III Aquinas Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Tomus Secundus Latin 1932 Hardcover 735 Book II Aquinas Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Tomus Quartus Latin 1932 Hardcover 809 Book IV Aquinas Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Tomus Quintus Latin 1932 Hardcover 819 Book V Aquinas Summa Theologica, Indices Et Lexicon, St. Thomas Latin 1932 Hardcover 438 Book VI Tomus Sextus Aquinas Lexicon Platonicum, D. Fridericus Ancient 1969 Hardcover 502 Vol. I Astius (Editor) Greek/Latin Lexicon Platonicum, D. Fridericus Ancient 1969 Hardcover 502 Vol. II Astius (Editor) Greek/Latin Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date Lexicon Platonicum, D. Fridericus Ancient 1969 Hardcover 502 Vol. III Astius (Editor) Greek/Latin The City of God Loeb Classical Library, Against the Pagans, Saint Augustine W. M. Green Latin/English 06/01/1963 Hardcover 544 No. 412 Books IV-VII The City of God Loeb Classical Library, Against the Pagans, Saint Augustine David Wiesen Latin/English 07/01/1968 Hardcover 584 No. 413 Books VIII-XI The City of God Loeb Classical Library, Against the Pagans, Saint Augustine Philip Levine Latin/English 06/01/1966 Hardcover 592 No. -

Loeb Classical Libary Titles

Middlebury College Classics Department Library Catalog: Loeb Classical Library Titles - Sorted by Author Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date A. S. Hunt Select Papyri I, Non-Literary Loeb Classical A. S. Hunt & C. Ancient (Editor) & C. C. 06/01/1932 Hardcover 472 Papyri, Private Affairs Library, No. 266 C. Edgar Greek/English Edgar (Editor) A. S. Hunt Select Papyri II, Non-Literary Loeb Classical A. S. Hunt & C. Ancient (Editor) & C. C. 06/01/1934 Hardcover 0 Papyri, Public Documents Library, No. 282 C. Edgar Greek/English Edgar (Editor) Loeb Classical Ancient Historical Miscellany Aelian Nigel Guy Wilson 06/01/1997 Hardcover 520 Library, No. 486 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 400 Animals I, Books I-V Library, No. 446 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 432 Animals II, Books VI-XI Library, No. 448 Greek/English On the Characteristics of Loeb Classical Ancient Aelian A. F. Scholfield 06/01/1958 Hardcover 464 Animals III, Books XII-XVII Library, No. 449 Greek/English The Speeches of Aeschines, Loeb Classical Charles Darwin Ancient Against Timarchus, On The Aeschines 06/01/1919 Hardcover 552 Library, No. 106 Adams Greek/English Embassy, Against Ctesiphon Aeschylus I, Suppliant Maidens, Persians, Loeb Classical Herbert Weir Ancient Aeschylus 12/01/1970 Hardcover 464 Prometheus, Seven Against Library, No. 145 Smyth Greek/English Thebes Aeschylus II, Agamemnon, Loeb Classical Aeschylus Herbert Weir Ancient 06/01/1960 Hardcover 624 Publish Title Subtitle Author Translator Language Binding Pages Date Libation-Bearers, Eumenides, Library, No. -

Horace for English Readers, Being a Translation of the Poems of Quintus

c x^. > ; ^ HORACE FOR ENGLISH READERS BEING A TRANSLATION OF THE POEMS OF QUINTUS HORATIUS FLACCUS INTO ENGLISH PROSE E. C. WICKHAM, D.D. DEAN OF LINCOLN HON'. FELLOW OF NEW CXFORU ; COLLEGE, OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS rpo3 HENRY FROWDE, M.A. PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD LONDON, EDINBURGH NEW YORK oc\'\'^7^022 aVp/ Animae qualem neque candidiorem Terra tulit, neque cui me sit devinctior alter. PREFACE Latin poet has been translated into verse, in this at more often than Horace. No country least, statesmen Perhaps the long list of poets, scholars, and who from generation to generation have tried their hands at the task may suggest the reflection that part of its fascination must consist in its insuperable difficulties. The humbler part of translating him into prose has been scantily attempted in England, though the example has been set us in France. By translation into prose I understand that which has been done for Virgil by for Conington and more lately by Mackail, Homer by Lang and his coadjutors, or again in part for Dante by Dr. Carlyle ^ translation which, while literal in the sense that is in its , every thought exactly represented _>--.^_^j4/<-^ ^ proper order, tone, and emphasis, has also just so much^^ of literary form that it can be read by a modern reader without distress, I and understood without perpetual reference to the and that Horace's original ; (to adapt own expression) if in the process the author be necessarily dismembered, the fragments can at least be recognized for those of a poet. -

Introduction BIBLIOGRAPHY Xii 1

Introduction BIBLIOGRAPHY xii 1. HORACE IN THE LATE 30s B.C. C. Witke, Latin Satire. The Structure of Persuasion (Leiden, 1970) T.P. Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate 139 B.C. - AD. 14 (Oxford, 1971) Horace's satires were composed in the politically uncertain and socially traumatic period Roman Studies Literary and Historical (Liverpool/New Hampshire, 1987) between Philippi and the aftermath of the battle of Actium (41-29 B.C.). In 42 B.C. in B.C. Woodcock, A New Latin Syntax (London, 1959, reprinted 1962) the Philippi campaign Horace served as military tribune under Brutus against Antony T. Zielinski, Horace et la societe romain du temps d'Auguste (paris, 1938) and Caesar's heir, the young Octavian. In 31 B.C. he supported, with his words if not F. Zoccali, 'Parodia e Moralismo nella Satira II, 5 di Orazio', Aui ddla Accademia also with his presence, Octavian's victorious campaign against Antony. This is also the Peloritani dei Perkolanti, Classe di Lettere Filosofia e Belle Arti 55 (1979). span of the Epodes (published about 30 B.C.). Actium, the great turning point, is given 303-321 pride of place in the frrst Epode, a poem on Horace's commitment to Maecenas and his cause. If the political context of Satires Book 1 (published about 35 B.C.) is Octavian's consolidation of power in Italy and the war against Sextus Pompeius (defeated 36 B.C.), in Book 2 the battle of Actium has been won and Octavian's power is acknowledged as supreme (Sat. 2.1.11, Caesaris invicti res). -

Satires I and 2

Horace, Satires I and 2 2 streets of Rome and a meditation on freedom, both personal and generic, but also as a deceptively sophisticated and allusive literary artefact. 6 EMILY GOWERS Horace alternates between calling his satires Satirae and Sermones, "Conversations," a title which suggests that they were simulating compan- The restless companion: Horace, ionable speech, with its aimless starts, slack inner logic, and throw-away Satires I and 2 endings, the kind friends tolerate and enemies overlook.? They are addressed primarily to his patron Maecenas, which makes everyone else into jealous eavesdroppers, but Horace is also by implication conversing with the small poetic coterie, including Virgil and Varius, to which he belonged (and which he puts on display in a triumphant rollcall at the end of book I), as well as being in constant intertextual dialogue with the wider community of poets, Horace's two books of Satires have always lurked in the shadow of the Odes. I dead and alive. 8 Aside from such favourite anecdotes as the much-translated encounter with Book I experiments with different kinds of sermo: diatribe (primarily a a literary gatecrasher on the Via Sacra, or the "granny's tale" of the town Hellenistic form associated with neo-Socratic or Cynic ranting on moral mouse and the country mouse,2 they have for the most part been found themes),9 gossip, literary chitchat. Sermones 1.1-3 are moralizing sermons, strange, profoundly unsatisfying poems, whose self-deprecating tone has the basic rules for life Horace claims to have learned at his father's knee _ condemned them to neglect. -

(Satires): Preparing for the Future As a Political Commentator

2 The Sermones (Satires): Preparing for the Future as a Political Commentator 2.1 Introduction to the Chapter Horace wrote two collections of Sermones, the name he gave his poems which are generally known as Satires.51 Book 1 of the Sermones is his debut. It is generally held that he began writing the book in 42 or 41 B.C. (although I will argue below that 38 B.C. is more likely), and that this was probably released in 36 or 35 B.C. Book 2 appeared five years later.52 He wrote the Epodi, and some of the Carmina and Epistulae, in the same period. In this monograph I will focus on the first book of Sermones (S.1). However, I will briefly consider in section 3.3 the political issues he raised in the second book of Sermones (S.2) and in two other genres he wrote in the period of 38 B.C until 30 B.C., the Epodi and a number of Carmina. The name of Sermones is a more appropriate representation of Horace’s intentions than the name of Satires. I suggest that Horace wrote in S.1 a lot about satire, but that it is not satiric blame poetry levelled directly at an audience: adapting the words of Schlegel (2005, 6) “he presents the bite [in S.1], but does not do the biting.” The view that Horace in S.1 didn’t write much satiric poetry is contrary to that of Freudenburg in 1993, where he presents Horace as “the satirist,” but conforms Freudenburg’s view in 2001.