Summary of Horace's Satires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caesars and Misopogon: a Linguistic Approach of Flavius Claudius Julianus’ Political Satires

The Buckingham Journal of Language and Linguistics 2015 Volume 8 pp 107-120 CAESARS AND MISOPOGON: A LINGUISTIC APPROACH OF FLAVIUS CLAUDIUS JULIANUS’ POLITICAL SATIRES. Georgios Alexandropoulos [email protected] ABSTRACT This study examines the linguistic practice of two political satires1 (Misopogon or Beard - Hater and Caesars) written by Flavius Claudius Julian2 the Emperor. Its purpose is to describe the way that Julian organizes the coherence and intertextuality of his texts and to draw conclusions about the text, the context of the satires and Julian’s political character. 1. INTRODUCTION Misopogon or Beard - Hater3, is a satirical essay and Julian’s reply to the people of Antioch who satirized him in anapestic verses and neglected his way of political thinking. The political ideology he represented was repelled by the Syrian populace and the corrupt officials of Antioch. Caesars is a Julian’s satire, in which all the emperors reveal the principles of their character and policy before the gods and then they choose the winner. Julian writes Caesars in an attempt to criticize the emperors of the past (mainly Constantine) whose worth, both as a Christian and as an emperor, Julian severely questions. He writes Misopogon when he decides to begin his campaign against the Persians. When he tried to revive the cult relative to ancient divine source of Castalia at the temple of Apollo in the suburb of Daphne, the priests mentioned that the relics of the Christian martyr Babylas prevented the appearance of God. Then Julian committed the great error to order the removal of the remains of the altar and thus they were accompanied by a large procession of faithful Christians. -

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires Thesis Advisor: Dr. William Wycislo Spring 2004 Acknowledgments My sincerest thanks go to Dr. Wycislo, without whose time and effort this project would have never have happened. Abstract Juvenal was a satirist who has made his mark on our literature and vernacular ever since his works first gained prominence (Kimball 6). His use of allusion and epic references gave his satires a timeless quality. His satires were more than just social commentary; they were passionate pleas to better his society. Juvenal claimed to give the uncensored truth about the evils that surrounded him (Highet 157). He argued that virtue and vice were replacing one another in the Roman Empire. In order to gain better understanding of his claim, in the following paper, I looked into his moral origins as well as his arguments on virtue and vice before drawing conclusions based on Juvenal, his outlook on society, and his solutions. Before we can understand how Juvenal chose to praise or condemn individuals and circumstances, we need to understand his moral origins. Much of Juvenal's beliefs come from writings on early Rome and long held Roman traditions. I focused on the writings of Livy, Cicero, and Polybius as well as the importance of concepts such as pietas andjides. I also examined the different philosophies that influenced Juvenal. The bulk of the paper deals with virtue and vice replacing one another. This trend is present in three areas: interpersonal relationships, Roman cultural trends, and religious issues. First, Juvenal insisted that a focus on wealth, extravagance, and luxury dissolved the common bonds between citizens (Courtney 231). -

Burial Customs and the Pollution of Death in Ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS and the POLLUTION of DEATH in ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES and PARADOXES

Burial customs and the pollution of death in ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS AND THE POLLUTION OF DEATH IN ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES AND PARADOXES ABSTRACT The Roman attitude towards the dead in the period spanning the end of the Republic and the high point of the Empire was determined mainly by religious views on the (im)mortality of the soul and the concept of the “pollution of death”. Contamina- tion through contact with the dead was thought to affect interpersonal relationships, interfere with official duties and prevent contact with the gods. However, considera- tions of hygiene relating to possible physical contamination also played a role. In this study the traditions relating to the correct preparation of the body and the sub- sequent funerary procedures leading up to inhumation or incineration are reviewed and the influence of social status is considered. Obvious paradoxes in the Roman at- titude towards the dead are discussed, e.g. the contrast between the respect for the recently departed on the one hand, and the condoning of brutal executions and public blood sports on the other. These paradoxes can largely be explained as reflecting the very practical policies of legislators and priests for whom considerations of hygiene were a higher priority than cultural/religious views. 1. INTRODUCTION The Roman approach to disposing of the dead in the Republican era and the early Empire (the period from approximately 250 BC to AD 250) was determined in part by diverse cultural/religious beliefs in respect of the continued existence of the soul after death and the con- cept of the “pollution of death”. -

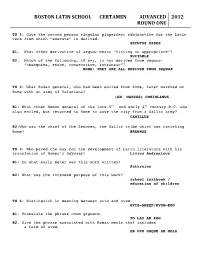

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

And Voltaire's

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POPE’S “ESSAY ON MAN” AND VOLTAIRE’S “DISCOURS EN VERS SUR L’HONME” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS BY ANNIE BERNICE WIMBUSH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ATLANTA, GEORGIA NAY 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . a a . • • • . iii. Chapter I. THENENANDTHEIRWORKS. a• • • • • . a aa 1 The Life of Alexander Pope The Life of Voltaire II. ABRIEFRESUNEOFTHETWOPOENS . aa • . • •. a a 20 Pope’s “Essay on Man” Voltaire’s “Discours En Vers Sur L’Hoimne” III. A COMPARISON OF THE TWO POEMS . a • • 30 B IBLIOGRAPHY a a a a a a a a a a a • a a a • a a a a a a a 45 ii PREFACE In the annals of posterity few men of letters are lauded with the universal renown and fame as are the two literary giants, Voltaire and Pope. Such creative impetus and “esprit” that was uniquely theirs in sures their place among the truly great. The histories and literatures of France and England show these twQ men as strongly influential on philosophical thinking. Their very characters and temperaments even helped to shape and transform man’s outlook on life in the eighteenth century and onward.. On the one hand, there is Voltaire, the French poet, philosopher, historian and publicist whose ideas became the ideas of hundreds of others and whose art remains with us today as monuments of a great mind. On the other there is Pope, the English satirical poet and philosopher, endowed with a hypersensitive soul, who concerned himself with the ordinary aspects of literary and social life, and these aspects he portrayed in his unique and excellent verse, Both men were deeply involved in the controversial issues of the time. -

Martial's and Juvenal's Attitudes Toward Women Lawrence Phillips Davis

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1973 Martial's and Juvenal's attitudes toward women Lawrence Phillips Davis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Davis, Lawrence Phillips, "Martial's and Juvenal's attitudes toward women" (1973). Master's Theses. Paper 454. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARTIAL' S AND JUVENAL' S ATTITUDES TOWARD WOMEN BY LAWRENCE PHILLIPS DAVIS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF·ARTS IN ANCIENT LANGUAGES MAY 1973 APPROVAL SHEET of Thesis PREFACE The thesis offers a comparison between the views of Martial and Juvenal toward women based on selected .Epigrams of the former and Satire VI of the latter. Such a comparison allows the reader to place in perspective the attitudes of both authors in regard to the fairer sex and reveals at least a portion of the psychological inclination of both writers. The classification of the selected Epigrams ·and the se lected lines of Satire VI into categories of vice is arbi- . trary and personal. Subjective interpretation of vocabulary and content has dictated the limits and direction of the clas sification. References to scholarship regarding the rhetori cal, literary, and philosophic influences on Martial and Ju venal can be found in footnote6 following the chapter concern-· ~ng promiscuity. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

DEATH in ROMAN MARCHE, ITALY: a COMPARATIVE STUDY of BURIAL RITUALS Presented by Antone R.E

DEATH IN ROMAN MARCHE, ITALY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BURIAL RITUALS _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by ANTONE R.E. PIERUCCI Dr. Kathleen Warner Slane, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled DEATH IN ROMAN MARCHE, ITALY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BURIAL RITUALS presented by Antone R.E. Pierucci, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Kathleen Warner Slane Professor Marcus Rautman Professor Carrie Duncan To my parents, for their support over the years. And for their support in the months to come as I languish on their couch eating fruit loops “looking for a job.” ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank the Department of Art History and Archaeology for the funding that allowed me to grow as a scholar and a professional these last two years; without the support this thesis would not have been possible. Secondly, I would like to thank my thesis Adviser, Dr. Kathleen Warner Slane, for the hours she spent discussing the topic with me and for the advice she provided along the way. The same goes for my committee members Dr. Rautman and Dr. Duncan for their careful reading of the manuscript and subsequent comments that helped produce the final document before you. And, of course, thanks must be given to my fellow graduate students, without whose helping hands and comforting shoulders (and the occasional beer) I would have long since lost touch with reality. -

A STUDY of SOCIAL LIFE in the SATIRES of JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., the University of British Columbia, 1959. A

A STUDY OF SOCIAL LIFE IN THE SATIRES OF JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1959. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission*. Department of Glassies The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada Date April 28, 196U ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is not to deal with the literary merit and poetic technique of the satirist. I am not asking whether Juvenal was a good poet or not; instead, I intend to undertake this study strictly from a social and historical point of view. From our author's barrage of bitter protests on the follies and foibles of his age I shall try to uncover as much of the truth as possible (a) from what Juvenal himself says, (b) from what his contemporaries say of the same society, and (c) from the verdict of modern authorities.