Satires I and 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

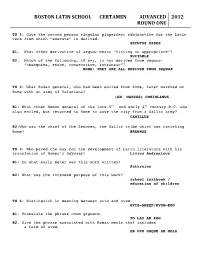

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

A Mixed Place: the Pastoral Symposium of Horace, Odes 1.17

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2018 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 2-2018 A Mixed Place: The aP storal Symposium of Horace Kristen Ehrhardt John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018 Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Ehrhardt, Kristen, "A Mixed Place: The asP toral Symposium of Horace" (2018). 2018 Faculty Bibliography. 14. https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2018/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2018 Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Mixed Place: The Pastoral Symposium of Horace, Odes 1.17 Kristen Ehrhardt ABSTRACT: When Horace invites Tyndaris to an outdoor drinking party in Odes 1.17, he mixes the locus amoenus of pastoral with the trappings of symposia. I argue that the mixture of the two poetic spaces creates a potentially volatile combination by muddling the expectations of each place’s safety and danger. I read 1.17 in light of other pastoral poems in Odes 1 to establish Horace’s creation of safe places through the negation of natural perils. Although pastoral has its own dangers, the addition of sympotic motifs in 1.17 attracts different beasts—sexual predators—to Tyndaris’ party. A central conceit of Horace’s pastoral poems is the preternatural safety of their speakers: despite whatever dangers might lurk in the natural realm, the speaker himself remains unharmed. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

Some Imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace

Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2015.12.31. "Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/some-imitations-of- pindar-and-sappho-by-horace/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39699959 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:CHS.Online_Publishing for a complete and continually expanding list of open access publications by CHS. -

Odes and Epodes (Loeb Classical Library) by Horace

Odes and Epodes (Loeb Classical Library) by Horace Ebook Odes and Epodes (Loeb Classical Library) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Odes and Epodes (Loeb Classical Library) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Loeb Classical Library (Book 33)+++Hardcover:::: 368 pages+++Publisher:::: Harvard University Press (June 1, 2004)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 9780674996090+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0674996090+++ASIN:::: 0674996097+++Product Dimensions::::4.2 x 1 x 6.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 9780674996090 ISBN13 978-0674996 Download here >> Description: The poetry of Horace (born 65 BCE) is richly varied, its focus moving between public and private concerns, urban and rural settings, Stoic and Epicurean thought. Here is a new Loeb Classical Library edition of the great Roman poets Odes and Epodes, a fluid translation facing the Latin text.Horace took pride in being the first Roman to write a body of lyric poetry. For models he turned to Greek lyric, especially to the poetry of Alcaeus, Sappho, and Pindar; but his poems are set in a Roman context. His four books of odes cover a wide range of moods and topics. Some are public poems, upholding the traditional values of courage, loyalty, and piety; and there are hymns to the gods. But most of the odes are on private themes: chiding or advising friends; speaking about love and amorous situations, often amusingly. Horaces seventeen epodes, which he called iambi, were also an innovation for Roman literature. Like the odes they were inspired by a Greek model: the seventh-century iambic poetry of Archilochus. -

A STUDY of SOCIAL LIFE in the SATIRES of JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., the University of British Columbia, 1959. A

A STUDY OF SOCIAL LIFE IN THE SATIRES OF JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1959. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission*. Department of Glassies The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada Date April 28, 196U ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is not to deal with the literary merit and poetic technique of the satirist. I am not asking whether Juvenal was a good poet or not; instead, I intend to undertake this study strictly from a social and historical point of view. From our author's barrage of bitter protests on the follies and foibles of his age I shall try to uncover as much of the truth as possible (a) from what Juvenal himself says, (b) from what his contemporaries say of the same society, and (c) from the verdict of modern authorities. -

HORACE (65-8 B.C.) More Visible (And As Such, More Threaten Latin Lyric and Satiric Poet of the Ing to the Homosocial Groups!

• HOMOSOCIALITY munitiescan be seen as a byproduct of this phie Freundschaftseros einschliesslich process of declining homosociality. Homoerotik, Homosexualitiit und die Whereas in former times much homosex verwandte und vergleichende Gebiete, Frankfurt am Main: Dipa Verlag. 1964. ual behavior existed under the cover of GertHekma homosociality, with the decline of male bonding, homosexualsituationsare stand ing more apart and are thus becoming HORACE (65-8 B.C.) more visible (and as such, more threaten Latin lyric and satiric poet of the ing to the homosocial groups!. GoldenAge. QuintusHoratiusFlaccuswas With the advent of the homosex the son of a freedman who cared for his ualidentity, thehomosocial male (soldier, education. In Athens he studied philoso seaman, cowboy, outlaw, fireman, cop! phy and ancient Greek literature. As a became the typical object of desire for supporter of Brutus he fought at Philippi, homosexual men, and when in the last thenreturned to Rome, whereinthe spring decades thisbordertraffic betweengay and of 38 VergH and Varius Rufus introduced straight societydiminished, somegay men him to Maecenas, thegreat patronofLatin in their IIclone" stereotypes tried to realize literature, who after nine months admit these homosocial types in themselves. ted him to his intimate circle. Horace Conclusion. Thesubjectofhomo thereafterlived withdrawn, diningoutonly sociality, and more specifically, of female at Maecenas' invitation. The friendship and male bonding, has great relevance for lasted to the end of their lives, and in 32 gay and lesbian studies. First, as a sphere Horace received from Maecenas a Sabine where forms of homosexual pleasure are estate. engendered, andsecondly, becauseitbroad As a poet Horace is remembered ens as well as changes the perspective of for his Odes, EpodBs, and Satires. -

Summary of Horace's Satires

Horace Satires Summary of Horace’s Satires Book One 1 The need to find contentment with one’s lot, and the need to acquire the right habits of living in a state of carefree simplicity rather than being a lonely sad miser. 2 The need to practise safe sex: i.e. sex with women who are available and with whom one can have carefree relations. Adultery is a foolish game as (a) one cannot inspect the women before ‘buying’ and (b) it brings huge risks to health and reputation both in the fear of discovery and in being discovered and punished. Epicurean ethics of ‘the little that is enough’ means that whatever is available as a sexual outlet is preferable to pining with love for the unattainable. 3 The need to be indulgent to the faults of our friends if we want them to be indulgent towards us. The poet gives a quick version of Epicurean anthropology to explain the origins of morality and to discount the rigidity of Stoic ethics. 4 Horace’s first literary manifesto. He discusses Lucilius’ outspoken frankness and says that his poems are not really poetry at all but ‘closer to everyday speech.’ His choice of subject-matter is motivated not by malice but by a gentle desire to help others with the sort of good advice which his father had given him. 5 The journey to Brundisium. Horace went with Maecenas and other influential men (including Virgil) to conduct diplomatic discussions with Mark Antony in Spring 37BC. The poem avoids any overt political comment and focusses instead on the details of the journey and the accommodation ‘enjoyed’ or not. -

I Horace and the Greek Lyric Tradition a Thesis Submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment Of

Horace and the Greek Lyric Tradition A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Anne Rekers Reidmiller May 2005 Oxford, Ohio i ABSTRACT HORACE AND THE GREEK LYRIC TRADITION by Anne Rekers Reidmiller Although the Roman poet Horace (65 – 8 BCE) is well known for his celebration of distinctively Roman and specifically Augustan themes, he was also heavily influenced by the traditions of Greek lyric poetry, particularly in the creation of his four books of Odes. This thesis uses close readings of selected poems from Horace, Sappho, Alcaeus, and Archilochus to examine the complex relationship between Horace and the Greek lyric poets who inspired him. The first section of this thesis establishes the claims that Horace himself makes about his relationship to the Greek poets through an examination of several poems in which he reflects on his status as a lyric poet. The second and third sections consist of comparative analysis in which poems of Horace are set against selections of Greek lyric. In the second section, this analysis is focused on the appearance of the personal voice or lyric ‘I’ in Horace’s poetry and in Greek lyric. In the third section, the focus shifts to the use of the lyric addressee, an aspect of the occasion or “moment” for which a poem is supposedly written. The conclusion applies these comparative arguments to a re- evaluation of Horace’s own claims, arriving at an assessment of Horace’s lyric achievement which suggests the necessity for a re-evaluation of Greek lyric as well. -

Ut Pictura Poesis: an Investigation of New Humanist Tendencies in The

Ut Pictura Poesis: An Investigation of New Humanist Tendencies in the Work of Cy Twombly Paige Alana Hirschey Art & Art History Departmental Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder April 7, 2014 Thesis Advisor Albert Alhadeff | Department of Art & Art History Committee Members Albert Alhadeff | Department of Art & Art History Robert Nauman | Department of Art & Art History Diane Conlin | Department of Classics Table of Contents Abstract................................................................................................................3 Introduction.........................................................................................................5 Chapter I: “Cy Was Here”...................................................................................9 Chapter II: Charles Olson, Black Mountain College, and New Humanism.......24 Chapter III: Twomby the ‘Istorian......................................................................39 Conclusion..........................................................................................................55 Images.................................................................................................................56 Bibliography........................................................................................................66 2 Abstract When Cy Twombly defected to Italy in 1957, he left, much to his delight, the scrutiny and criticism of the New York art world behind. But as much as the artist enjoyed the freedom that isolation afforded him, the result -

The Use of the Countryside in Horace's Odes

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Foliate Lyre: The Use of the Countryside In Horace's Odes by Andrew Michael Goldstein Class of 2002 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Classics Introduction The tradition oflyric poetry had long been dormant-analyzed and categorized by the Alexandrian bookkeeper-poets, then shuttled away onto a shelf in the form of the Anthology-when Horace breathed new life into the genre with the Odes. In the Odes, Horace awakened the old voices of lyric poetry, the exuberant, spontaneous voices of ancient Greece, and adapted them into a unique genre of Latin lyric that bore his own poetic mark. He revived many of the themes of Greek lyric, retouching them slightly to apply to Roman life in the burgeoning empire of Augustus, but his also added an element of his own. In Greek lyric, themes oflove, war, politics, and the symposium were pervasive and during the centuries when the genre had originally flourished these themes were addressed in subtle and original ways by poets who became famous for their individual voices throughout all Greece. The depiction of the natural world, however, was almost entirely absent from Greek lyric poetry, and when it was addressed in a poem is was merely as a compositional element, a piece of scenery to create a certain atmosphere. More than six hundred years after Archilochus invented lyric poetry on the island of Paros, Horace introduced for the first time a vivid natural world into the genre, an entire rustic landscape with its own inhabitants and values, traditions and beliefs.