The Senses and Synaesthesia in Horace's Satires by Amy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caesars and Misopogon: a Linguistic Approach of Flavius Claudius Julianus’ Political Satires

The Buckingham Journal of Language and Linguistics 2015 Volume 8 pp 107-120 CAESARS AND MISOPOGON: A LINGUISTIC APPROACH OF FLAVIUS CLAUDIUS JULIANUS’ POLITICAL SATIRES. Georgios Alexandropoulos [email protected] ABSTRACT This study examines the linguistic practice of two political satires1 (Misopogon or Beard - Hater and Caesars) written by Flavius Claudius Julian2 the Emperor. Its purpose is to describe the way that Julian organizes the coherence and intertextuality of his texts and to draw conclusions about the text, the context of the satires and Julian’s political character. 1. INTRODUCTION Misopogon or Beard - Hater3, is a satirical essay and Julian’s reply to the people of Antioch who satirized him in anapestic verses and neglected his way of political thinking. The political ideology he represented was repelled by the Syrian populace and the corrupt officials of Antioch. Caesars is a Julian’s satire, in which all the emperors reveal the principles of their character and policy before the gods and then they choose the winner. Julian writes Caesars in an attempt to criticize the emperors of the past (mainly Constantine) whose worth, both as a Christian and as an emperor, Julian severely questions. He writes Misopogon when he decides to begin his campaign against the Persians. When he tried to revive the cult relative to ancient divine source of Castalia at the temple of Apollo in the suburb of Daphne, the priests mentioned that the relics of the Christian martyr Babylas prevented the appearance of God. Then Julian committed the great error to order the removal of the remains of the altar and thus they were accompanied by a large procession of faithful Christians. -

Translated by Wordport from Nota Bene Ver. 4 Document EPODE.599

http://akroterion.journals.ac.za THE INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIETY: AN ORGANISING PRINCIPLE IN HORACE’S EPODES? Sjarlene Thom (University of Stellenbosch) Over the years there have been various attempts to make sense of the Epodes as a collection, as well as of individual poems.1 Scholars who have focussed on the collection as a whole have tried generally grouping the poems according to metre2 or to subject matter into either different areas of criticism or different categories of invective.3 The subsequent scholarly debate centred on arguments why individual groups were identified and why a specific poem should fall into a specific group. My personal reaction to these attempts to structure the collection according to groups is rather negative for the following simple reason: too many persuasive alternatives are possible. No musical composition could at one and the same time be described for instance as a sonata, a suite or a prelude and fugue. If a piece of music displays characteristics of all these musical forms, a broader organisational principle has to be found to accommodate the individual sections. In the same way then – since so many different possible ways have been identified in which to pack out various groups of Epodes – it seems to make more sense to look at the Epodes as a unit in which a variety of cross-references or, to continue the musical analogy, variations on a theme, all support a central statement. There have also been scholars who focused on individual poems who have come up with striking or even ingenious individual interpretations, but more often than not they then ignored or discounted the larger unit in which the poems functioned. -

Questioning the 'Witch' Label: Women As Evil in Ancient Rome

Questioning the ‘witch’ label: women as evil in ancient Rome Linda McGuire Introduction It became popular during the early Roman Empire for authors to depict women using magic in their writing. Such women appeared in almost every literary genre (satire, love poetry, epic and novels) during a span of 150 years. They can be found in the works of Virgil, Horace, Tibullus, Propertius, Ovid, Lucan, Petronius and Apuleius. They were not a particularly coherent group, although they share certain common characteristics. Besides their link with magic there is only one other thing that they all share in common – these women are called witches by scholars today regardless of the Latin terminology used to refer to them.1 What these scholars mean when they use the term ‘witch’ is difficult to know as this English word, which has associations with modern European history, is never explained. This paper seeks to question the validity of using this modern term in the context of an ancient society, in this case Rome. First of all, what do scholars mean by ‘witch’ today and what ideas lie behind this term. Second, what similarities exist between the witches of the late Middle Ages and women using sorcery in Latin literature? As the topic is broad, this paper will focus specifically on the crimes of these women. Finally, who in Roman society were connected with particularly evil or unnatural crimes such as baby killing or cannibalism? Was it magic practitioners or others in society? Part one: witches and their crimes First found in a ninth century manuscript, the term ‘witch’ is thought to derive from the old English word wicca, meaning someone who casts a spell.2 It is likely, however, that our understanding of the term today is influenced from the period known as the witch-hunts which affected most of Europe in the late Middle Ages and resulted in the deaths of many thousands of people. -

Witches, Pagans and Historians. an Extended Review of Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000

[The Pomegranate 18.2 (2016) 205-234] ISSN 1528-0268 (print) doi: 10.1558/pome.v18i2.32246 ISSN 1743-1735 (online) Witches, Pagans and Historians. An Extended Review of Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000 Ronald Hutton1 Department of Historical Studies 13–15 Woodland Road Clifton, Bristol BS8 1TB United Kingdom [email protected] Keywords: History; Paganism; Witchcraft. Max Dashu, Witches and Pagans: Women in European Folk Religion, 700–1000 (Richmond Calif.: Veleda Press, 2016), iv + 388 pp. $24.99 (paper). In 2011 I published an essay in this journal in which I identified a movement of “counter-revisionism” among contemporary Pagans and some branches of feminist spirituality which overlapped with Paganism.2 This is characterized by a desire to restore as much cred- ibility as possible to the account of the history of European religion which had been dominant among Pagans and Goddess-centered feminists in the 1960s and 1970s, and much of the 1980s. As such, it was a reaction against a wide-ranging revision of that account, largely inspired by and allied to developments among professional historians, which had proved influential during the 1990s and 2000s. 1. Ronald Hutton is professor of history, Department of History, University of Bristol 2. “Revisionism and Counter-Revisionism in Pagan History,” The Pomegranate, 13, no. 2 (2011): 225–56. In this essay I have followed my standard practice of using “pagan” to refer to the non-Christian religions of ancient Europe and the Near East and “Pagan” to refer to the modern religions which draw upon them for inspiration. -

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2016 Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Damer, Erika Zimmermann. "Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12." Helios 43, no. 1 (2016): 55-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 ERIKA ZIMMERMANN DAMER When in Book 1 of his Epistles Horace reflects back upon the beginning of his career in lyric poetry, he celebrates his adaptation of Archilochean iambos to the Latin language. He further states that while he followed the meter and spirit of Archilochus, his own iambi did not follow the matter and attacking words that drove the daughters of Lycambes to commit suicide (Epist. 1.19.23–5, 31).1 The paired erotic invectives, Epodes 8 and 12, however, thematize the poet’s sexual impotence and his disgust dur- ing encounters with a repulsive sexual partner. The tone of these Epodes is unmistakably that of harsh invective, and the virulent targeting of the mulieres’ revolting bodies is precisely in line with an Archilochean poetics that uses sexually-explicit, graphic obscenities as well as animal compari- sons for the sake of a poetic attack. -

An Intertextual Approach to Metapoetic Magic in Augustan Love-Elegy and Related Genres

Durham E-Theses Asking for the Moon: An Intertextual Approach to Metapoetic Magic in Augustan Love-Elegy and Related Genres CHADHA, ZARA,KAUR How to cite: CHADHA, ZARA,KAUR (2014) Asking for the Moon: An Intertextual Approach to Metapoetic Magic in Augustan Love-Elegy and Related Genres, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10559/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract Asking for the Moon: An Intertextual Approach to Metapoetic Magic in Augustan Love- Elegy and Related Genres Zara Kaur Chadha This thesis offers a new perspective on the metapoetic use of magic in the love-elegies of Propertius, Tibullus, and Ovid, a theme which, though widely acknowledged in contemporary scholarship, has so far received little comprehensive treatment. The present study approaches the motif through its intertextual dialogues with magic in earlier and contemporary texts — Theocritus’ Idyll 2, Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica, Vergil’s Eclogue 8 and Horace’s Epodes — with the aim of investigating the origin and development of love-elegy’s self- construction as magic and of the association of this theme with poetic enchantment, deceit, and failure throughout the genre. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires

Emily Savage Virtue and Vice in Juvenal's Satires Thesis Advisor: Dr. William Wycislo Spring 2004 Acknowledgments My sincerest thanks go to Dr. Wycislo, without whose time and effort this project would have never have happened. Abstract Juvenal was a satirist who has made his mark on our literature and vernacular ever since his works first gained prominence (Kimball 6). His use of allusion and epic references gave his satires a timeless quality. His satires were more than just social commentary; they were passionate pleas to better his society. Juvenal claimed to give the uncensored truth about the evils that surrounded him (Highet 157). He argued that virtue and vice were replacing one another in the Roman Empire. In order to gain better understanding of his claim, in the following paper, I looked into his moral origins as well as his arguments on virtue and vice before drawing conclusions based on Juvenal, his outlook on society, and his solutions. Before we can understand how Juvenal chose to praise or condemn individuals and circumstances, we need to understand his moral origins. Much of Juvenal's beliefs come from writings on early Rome and long held Roman traditions. I focused on the writings of Livy, Cicero, and Polybius as well as the importance of concepts such as pietas andjides. I also examined the different philosophies that influenced Juvenal. The bulk of the paper deals with virtue and vice replacing one another. This trend is present in three areas: interpersonal relationships, Roman cultural trends, and religious issues. First, Juvenal insisted that a focus on wealth, extravagance, and luxury dissolved the common bonds between citizens (Courtney 231). -

Magic in Private and Public Lives of the Ancient Romans

COLLECTANEA PHILOLOGICA XXIII, 2020: 53–72 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-0319.23.04 Idaliana KACZOR Uniwersytet Łódzki MAGIC IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC LIVES OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS The Romans practiced magic in their private and public life. Besides magical practices against the property and lives of people, the Romans also used generally known and used protective and healing magic. Sometimes magical practices were used in official religious ceremonies for the safety of the civil and sacral community of the Romans. Keywords: ancient magic practice, homeopathic magic, black magic, ancient Roman religion, Roman religious festivals MAGIE IM PRIVATEN UND ÖFFENTLICHEN LEBEN DER ALTEN RÖMER Die Römer praktizierten Magie in ihrem privaten und öffentlichen Leben. Neben magische Praktik- en gegen das Eigentum und das Leben von Menschen, verwendeten die Römer auch allgemein bekannte und verwendete Schutz- und Heilmagie. Manchmal wurden magische Praktiken in offiziellen religiösen Zeremonien zur Sicherheit der bürgerlichen und sakralen Gemeinschaft der Römer angewendet. Schlüsselwörter: alte magische Praxis, homöopathische Magie, schwarze Magie, alte römi- sche Religion, Römische religiöse Feste Magic, despite our sustained efforts at defining this term, remains a slippery and obscure concept. It is uncertain how magic has been understood and practised in differ- ent cultural contexts and what the difference is (if any) between magical and religious praxis. Similarly, no satisfactory and all-encompassing definition of ‘magic’ exists. It appears that no singular concept of ‘magic’ has ever existed: instead, this polyvalent notion emerged at the crossroads of local custom, religious praxis, superstition, and politics of the day. Individual scholars of magic, positioning themselves as ostensi- bly objective observers (an etic perspective), mostly defined magic in opposition to religion and overemphasised intercultural parallels over differences1. -

Burial Customs and the Pollution of Death in Ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS and the POLLUTION of DEATH in ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES and PARADOXES

Burial customs and the pollution of death in ancient Rome BURIAL CUSTOMS AND THE POLLUTION OF DEATH IN ANCIENT ROME: PROCEDURES AND PARADOXES ABSTRACT The Roman attitude towards the dead in the period spanning the end of the Republic and the high point of the Empire was determined mainly by religious views on the (im)mortality of the soul and the concept of the “pollution of death”. Contamina- tion through contact with the dead was thought to affect interpersonal relationships, interfere with official duties and prevent contact with the gods. However, considera- tions of hygiene relating to possible physical contamination also played a role. In this study the traditions relating to the correct preparation of the body and the sub- sequent funerary procedures leading up to inhumation or incineration are reviewed and the influence of social status is considered. Obvious paradoxes in the Roman at- titude towards the dead are discussed, e.g. the contrast between the respect for the recently departed on the one hand, and the condoning of brutal executions and public blood sports on the other. These paradoxes can largely be explained as reflecting the very practical policies of legislators and priests for whom considerations of hygiene were a higher priority than cultural/religious views. 1. INTRODUCTION The Roman approach to disposing of the dead in the Republican era and the early Empire (the period from approximately 250 BC to AD 250) was determined in part by diverse cultural/religious beliefs in respect of the continued existence of the soul after death and the con- cept of the “pollution of death”. -

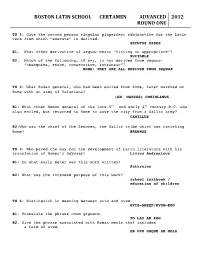

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods.