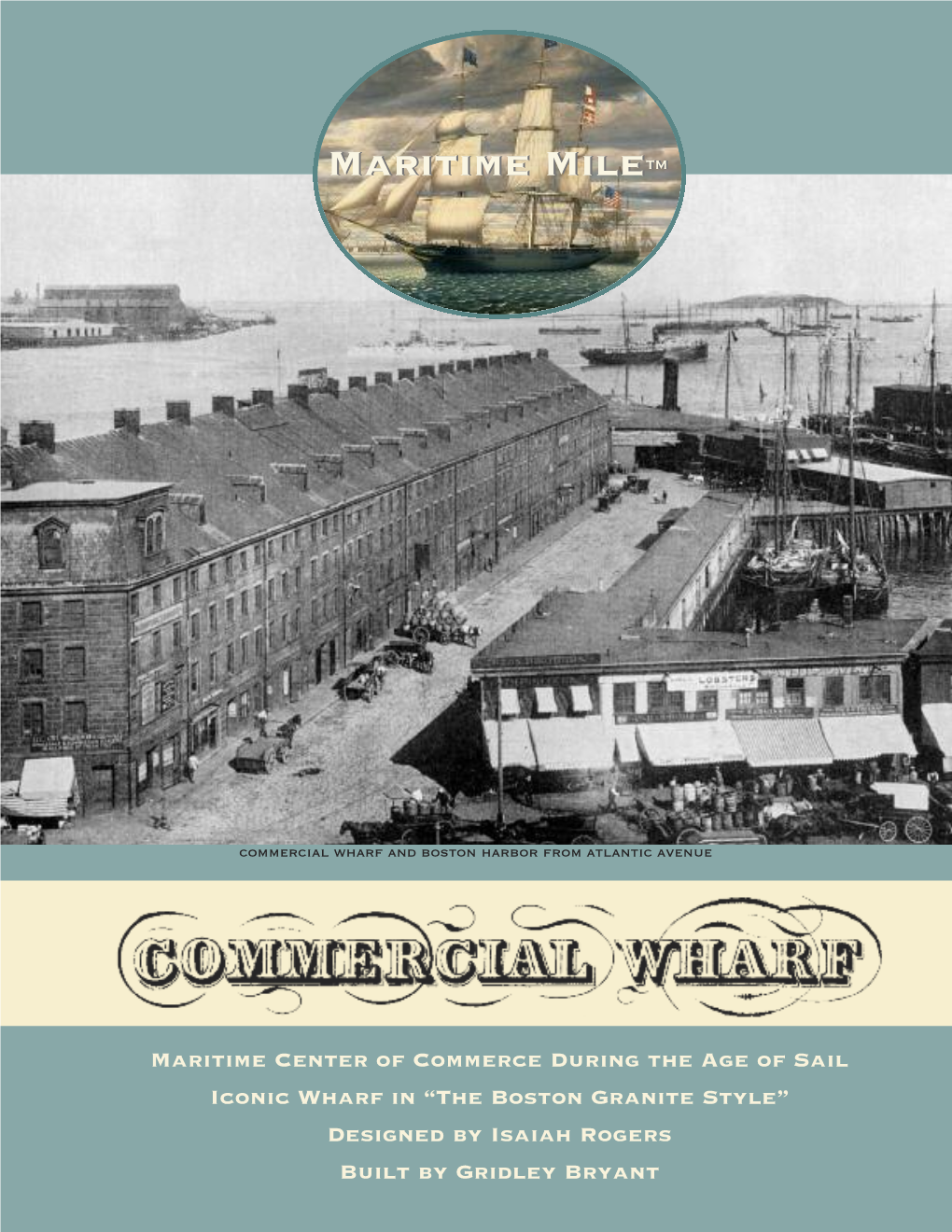

Commercial Wharf Historic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Nashville, Literary Department Building HABS No. TN-18 (Now Children's Museum) O 724 Second Avenue, North M Nashville Davidson County HAB'j Tennessee

University of Nashville, Literary Department Building HABS No. TN-18 (now Children's Museum) o 724 Second Avenue, North m Nashville Davidson County HAB'j Tennessee PHOTOGRAPHS § HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Architectural and Engineering Record National Park Service 1 Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 &S.TENN. fl-NA^H. ISA I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. TM-18 UNIVERSITY OF NASHVILLE, LITERARY DEPARTMENT BUILDING (now Children7s Museum) > v. >- Location: 724 Second Avenue, South, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee Present Owner: Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County Significant: Begun in 1853 by Major Adolphus Herman, one of Nashville's pioneer architects, the main building for the University of Nashville inaugurated the rich tradition of collegiate Gothic architecture in Nashville. Housing the Literary Department of the University, the building was one of the first permanent structures of higher learning in the city. The University of Nashville was one of the pioneer educa- tional institutions in the State of Tennessee, its ancestry antedating Tennessee statehood. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History 1. Date of Erection: The cornerstone was laid on April 7, 1853. The completed building was dedicated on October 4, 1854. 2' Architect; Adolphus Heiman. However, he was not the architect first selected by the Board of Trustees, their initial choice having been the eminent Greek Revivalist Isaiah Rogers, WUJ had moved from Boston to Cincinnati. On March 4, 1852, the Building Committee of the Board of Trustees for the University of Nash- ville reported that they had engaged the services of Isaiah Rogers, then of Cincinnati, as architect. -

Phi Gamma Delta Convention and Ekklesia Sites Many Convention and Ekklesia Sites Are Detailed Under Various City and State Location Pages

Phi Gamma Delta Convention and Ekklesia Sites Many convention and Ekklesia sites are detailed under various city and state location pages. We repeat those Ekklesia meeting locations here and add the over forty other locales where Phi Gamma Delta has held its conventions. The order is chronological by the first convention held at each site. Thus, the Bates House appears at 1872 along with the later conventions it hosted (1878, 1883 and 1890). Phi Gamma Delta held over 150 conventions at 70 different sites in 49 cities spread between 22 states, the District of Columbia, one province, and a foreign country (the Bahamas). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania - Arthur's Hall 1852 Convention At this time, we do not know the location of the August 5th, 1852 convention. However, a newspaper editorial describes public exercises at "Arthur's Hall." The entertainment consisted of orations, poems, music, and the like. The editorial was highly complementary of those presenting. This address was the location of attorneys' offices and a storefront in the 1850s. Arthur's Hall is listed in the 1852 city directory and is also mentioned in records of 1854. 44 Grant Street Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Cincinnati, Ohio - Burnet House (site only) 1856 Convention Completed in 1850 as a veritable palace and to wide acclaim, the Burnet House hotel was designed by noted architect Isaiah Rogers. It featured a forty-two-foot-wide central dome and 342 rooms. The hotel stood until 1926; the Union Central Building Annex replaced it. Four chapters met in convention on August 16-17, 1856. Burnet House c. 1850 Northwest corner, Third Street and Vine Street from The Illustrated London News Cincinnati, Ohio Louisville, Kentucky - United States Hotel 1859 Convention We do not yet have any data on this hotel. -

OLD ADMINISTRATION BUILDING (Third District U.S. Lighthouse Depot) U.S

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25; ·1980 List 138 LP-1112 OLD ADMINISTRATION BUILDING (Third District U.S. Lighthouse Depot) U.S. Coast Guard Station, 1 Bay Street, Borough of Staten Island. Built 1868-71; architect Alfred B. Mullett. Landmark Site: Borough of Staten Island Tax Map Block 1, Lot 55 in part, consisting of the land on which the described building is sit uated. On December 11, 1979, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Old Administration Building (Third District U.S. Lighthouse Depot), U.S. Coast Guard Station, (Item No. 18). The hearing had been duly adver tised in accordance with the provisions of the law. One witness spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. Letters have been received in favor of designation. The Commission had previously held a public hearing on the pro posed designation of the item as a landmark in 1966. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The three-story granite and red brick Second Empire style building which occupies a central location on the grounds of the former Coast Guard Station at the foot of Bay Street, St. George, Staten Island, has had a long and distinguished history of government service; first as the main office of the Lighthouse Service Depot for the Third Lighthouse District, and later as the Administration Building when the compound became a United StateS' Coast Guard Base. Well built, of fine design and materials, this building is expres sive of the era when, under the direction of Alfred B. -

December 2011 Page 1

President's Message It is hard to believe that my term as President of MCMA is nearly 2/3 over, and I continue to be both honored and humbled by this great experience. I continue also to be deeply appreciative of the cooperation and support I am afforded by our members, committees, Board of Government, Past- Presidents, and especially Ric Purdy, and I sincerely thank all of you. For the last few years our investment portfolio has suffered along with the economy as a whole, and this year has shown little improvement. So again, we remind that, if you are able to and wish to make a year- end donation to MCMA, your gift will be greatly appreciated. It is tax-deductible (Ric Purdy will send a written acknowledgement), and you may instruct Ric to record it as an anonymous contribution if you so desire. We don't ask that you give until it hurts, but please give until it feels good. All donations help to reduce our dependence on portfolio performance as our sole means of support and survival. (A SASE is enclosed for your use, or you can use the PayPal feature on our website.) Bill Anderson Recent Happenings We held our October Quarterly at the Neighborhood Club in Quincy, where we enjoyed a very nice meal in a comfortable atmosphere. [The Neighborhood Club has long been one of our favorite venues for these meetings, and although we must apologize for the fact that it is not so easily accessible as some of the other locations we use, it is always dependable and surprisingly cost effective.] President Anderson conducted the business portion of the meeting, appointed a three-man Nominations Committee (Vice- President Richard Adams plus Trustees Arthur Anthony and John Lordan), and announced that past- trustee Peter Lemonias has agreed to head up a committee to begin the planning for our 2013 Triennial. -

Picturing Emerson: an Iconography

Picturing Emerson: An iconography The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Myerson, Joel, and Leslie Perrin Wilson. 2017. Picturing Emerson: An iconography. Harvard Library Bulletin 27 (1-2), Spring-Summer 2016. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37363343 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Picturing Emerson: An Iconography Joel Myerson and Leslie Perrin Wilson HOUGHTON LIBRARY 2016 Distributed by Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England A Special Double Issue of the Harvard Library Bulletin Volume 27: Numbers 1-2 HARVARD LIBRARY BULLETIN VOLUME 27: NUMBERS 1–2 (SPRING–SUMMER 2016) PUBLISHED MARCH 2017 ISSN 0017-8136 Editor Coordinating Editor William P. Stoneman Dennis C. Marnon ADVISORY BOARD Bernard Bailyn Adams University Professor, Emeritus • Charles Berlin Lee M. Friedman Bibliographer in Judaica in the Harvard College Library • Ann Blair Henry Charles Lea Professor of History • Lawrence Buell Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature • Robert Darnton Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor and University Librarian, Emeritus • Roger E. Stoddard Senior Curator in Houghton Library, retired • Richard F. Thomas Professor of Greek and Latin • Helen Vendler A. Kingsley Porter University Professor • Christoph J. Wolff Adams University Professor • Jan Ziolkowski Arthur Kingsley Porter Professor of Medieval Latin The Harvard Library Bulletin is published three times a year, by Houghton Library. -

Some Aspects Profession of the Development of the Architectural in Boston Between 1800 and 1830 L

Some Aspects of the Development of the Architectural Profession in Boston Between 1800 and 1830 l JACK QUINAN* T he distinction between house- The earliest architectural school in Bos- wrights and gentlemen amateurs in ton has been attributed by several scholars 1 American architecture of the to Asher Benjamin at a date close to 1805.2 eighteenth century standsin sharpcontrast Unfortunately, the school has never been to the architectural profession as it de- adequately documented. Benjamin had veloped during the nineteenth century. In a submitted the following proposal for an little more than fii years “polite” ar- architectural school to the Windsor [Ver- chitecture ceased to be the occasional mont] Gazette of 5 January 1802. which preoccupationof a few educatedgentlemen seemsto have led Talbot Hamlin and Roger and emerged as a true profession, that is, Hale Newton to conclude that Benjamin one in which its practitioners could support subsequently established a school in Bos- themselves by designing buildings. The ton: change was momentous, and we may well ask how it came about. The topic is broad, To Young Carpenters. Joiners and All of course, and this paper shag be confmed Others concerned in the Art of building: to events in Boston with the hope that -The subscriberintends to opena School of Architectureat hishouse in Windsor, the similar studiesof other American cities will 20th of February next-at which will be soon follow. taughtThe Five Ordersof Architecture,the In a period of intense activity between Proportionsof Doors, Windows and Chim- 1800 and 1830 a number of architectural neypieces,the Constructionof Stairs, with schools, professional organizations, ar- their ramp and twist Rails, the method of farmitg timbers, lengthand backing of Hip chitectural libraries, and other related rafters,the tracingof groinsto AngleBrac- phenomena, materialized and provided the kets, circular soffitsin circularwalls; Plans, groundwork for the new profession in Bos- Elevationsand Sectionsof Houses,with all ton. -

Gu Cheng and Walt Whitman

Whitman East & West the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor Whitman East & West New Contexts for Reading Walt Whitman edited by ed folsom university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2002 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America http://www.uiowa.edu/uiowapress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitman East and West: new contexts for reading Walt Whitman /edited by Ed Folsom. p. cm.—(The Iowa Whitman series) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87745-821-9 (cloth) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Appreciation—Asia. 3. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Knowledge—Asia. 4. Books and reading—Asia. 5. Asia—In literature. I. Folsom, Ed, 1947–. II. Series. ps3238 .w46 2002 811Ј.3—dc21 2002021133 02 03 04 05 06 c 54321 for robert strassburg, who has put Whitman’s words to work in his music, his teaching, and his life. His performance of his Whitman compositions in Bejing literally set the tone for the “Whitman 2000” conference. -

THOMAS GAFF HOUSE (Hillforest) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THOMAS GAFF HOUSE (Hillforest) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Thomas Gaff House Other Name/Site Number: Hillforest 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 213 Fifth Street Not for publication:. City/Town: Aurora Vicinity:. State: IN County: Dearborn Code: 18 Zip Code: 47001 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 1 buildings ____ sites ____ structures ____ objects _1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 3 Name of related multiple property listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THOMAS GAFF HOUSE (Hillforest) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Chronology of John Brown Portraits – Photo Images Workshop Study (Jean Libby)

"The Late Unpleasantness” January 2009 South Bay Civil War Round Table San Jose, California January 27th Meeting Speaker: Holder's Country Inn (408) 244-2798 Charles Sweeny on “Aspects of 998 South De Anza Blvd. (near Bollinger) Slavery during the Civil War” San Jose, California Board Members President: Gary Moore Publicity Director: Bill Noyes (408)356-6216 [email protected] (408)374-1541 [email protected] Vice President: Larry Comstock Preservation Chairman: John Herberich (408)268-5418 [email protected] (408)506-6214 [email protected] Treasurer: Renee Accornero Membership Chairman: Fred Rohrer (408)268-7363 (510)651-4484 [email protected] [email protected] Newsletter Editor: Bob Krauth Recording Secretary: Kevin Martinez (408)578-0176 [email protected] (408)455-3367 [email protected] PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Let me begin by wishing each of you a belated Happy New Year as we embark on the year 2009. I sincerely hope your holidays were enjoyable ones. On a personal note, I continue to make rather remarkable progress in my recovery from the stroke I suffered in late October. I have progressed from a wheelchair to a walker, to a cane, and am now walking unassisted, albeit it with caution. My right arm and fine motor skills have made tremendous improvement and I can now write rather legibly, comb my hair, button my shirt, and as you can see from this message, use the computer keyboard. For all this progress I feel truly blessed and am extremely grateful. I am equally thankful for the cards, phone calls, e-mails, and thoughtful good wishes from each of you. -

A Bird's-Eye View of Modernity: the Synoptic View in Nineteenth-Century Cityscapes

A Bird's-Eye View of Modernity: The Synoptic View in Nineteenth-Century Cityscapes by Robert Evans A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Institute of Comparative Studies in Literature, Art and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Robert Evans Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87765-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87765-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

CHAMPAIGN CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL 144Th ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT Tommy Stewart Field MAY 25, 2021

CHAMPAIGN CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL 144th ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT \ Tommy Stewart Field MAY 25, 2021 CHAMPAIGN CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM Tuesday, May 25, 2021 Champaign Central High School’s commencement is a joyous and formal celebration of our students’ – your children’s - personal academic accomplishment. It is an historic ceremony attended with traditional dignity and respect for the members of the Class of 2021 and their families. As a diverse school family, we have all come together to celebrate. As we do, each in our own style, let us remember to be respectful of one another’s customs. Please do not allow your private affirmation of success, your support of your own child in whatever form that takes, to overshadow the reading of our students’ names. Kindly be brief. Thank you for your cooperation. Processional ......................................................................................................................................... Champaign Central High School Band "Fanfare and Processional - Pomp and Circumstance" by Edward Elgar Arranged by James D. Ployhar Directed by Mr. John Currey Class Welcome ..................................................................................................................................................................... Judson F. Wagner President, Class of 2021 Musical Selection ................................................................................................................ Champaign Central High School Chamber Choir "Homeward Bound" Words and Music -

President Andrew Johnson's Pottier & Stymus

Bolstering a National Identity: President Andrew Johnson’s Pottier & Stymus Furniture in the United States Treasury Department, 1865 Elizabeth Chantale Varner Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts Masters Program in the History of Decorative Arts The Smithsonian Associates and Corcoran College of Art + Design 2008 © 2008 Elizabeth Chantale Varner All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Lists of Illustrations ii Chapter 1: The Treasury Suite Furniture in the Cultural Context of Establishing a National Identity 1 Chapter 2: The Pottier & Stymus Commission 11 Chapter 3: Pottier & Stymus and the Renaissance Revival Style Furniture 25 Chapter 4: Shields on the Treasury Furniture Suite 43 Chapter 5: Influence of the Treasury Furniture Suite on Other Government Furniture 53 Bibliography 65 Illustrations 74 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 “The First Cabinet Meeting under the Administration of Andrew Johnson,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. 74 Figure 2 “The First Reception of Ambassadors by Andrew Johnson, at His Rooms in the Treasury Building Reception,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. 75 Figure 3 Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, 1796. 76 Figure 4 Ralph Earl, Andrew Jackson, 1830-1832. 77 Figure 5 Joseph Goldsborough Bruff, Cornelius and Baker Eagle Bracket in the Treasury Building, 1859. 78 Figure 6 The Maison Carrée, a Temple in Nîmes, France, c. 20 B.C. 79 Figure 7 United States Treasury Department Building, Washington, D.C., 1836-1869. 80 Figure 8 Pottier & Stymus, Sofa, United States Treasury Department, 1864. 81 Figure 9 Unknown, Sofa, ca. 1860-1870. 82 Figure 10 Unknown, Sofa, Virginia Museum of Art, ca.