Picturing Emerson: an Iconography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Visitor Who Never Comes: Emerson and Friendship

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 The Visitor Who Never Comes: Emerson and Friendship Wallace Coleman Green Jr. College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Green, Wallace Coleman Jr., "The Visitor Who Never Comes: Emerson and Friendship" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625830. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-xxw7-ck83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VISITOR WHO NEVER COMES: EMERSON AND FRIENDSHIP A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Wallace Coleman Green, Jr 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1993 Robert Sieholnick, Director ichard Lowry -L Adam Potkay ii TABLE OF CONTENTS APPROVAL SHEET ............................................ ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................... iv ABSTRACT .................................................. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Das Amerikabild Fredrika Bremers und ihre Vermittlungsarbeit in Schweden“ Verfasserin Michaela Pichler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra (Mag.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A057/393 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Individuelles Diplomstudium: Literatur- und Verlagskunde Betreuer: Dr. Ernst Grabovszki Böckerna ha blivit mitt käraste sällskap och betraktelsen en vän, som följer mig livet igenom och låter mig suga honung ur livets alla örter, även de bittra. Fredrika Bremer I Bedanken möchte ich mich bei meinem Betreuer Dr. Ernst Grabovszki, bei meinem Hauptkorrekturleser und guten Freund Johannes (Yogi) Rokita, sowie bei allen anderen, die durch Zuspruch und auffangende Worte ein Fertigstellen dieses Projektes direkt & indirekt unterstützt und dadurch ermöglicht haben! DANKE! II INHALTSVERZEICHNIS: 1 Einleitung ______________________________________________________ 1 2 Theoretische Grundlagen / Definitionen ______________________________ 5 2.1 Imagologie _______________________________________________________ 5 2.1.1 Image – Mirage ________________________________________________________ 8 2.1.2 Autoimage/Heteroimage ________________________________________________ 9 2.1.3 Xenologie, Stereotyp, Klischee ____________________________________________ 9 2.2 Reisebericht als Literaturgattung ____________________________________ 10 2.3 Auswandererbericht/Auswandererbrief ______________________________ -

Emerson Society Papers

Volume 8, Number 1 Spring 1997 Emerson Society Papers Emerson, Adin Ballou, and Reform Len Gougeon University ofScranton While most Emersonians are familiar with Emerson's the following year the group established itself on 250 acres considered rejection of George Ripley's invitation to join of land in Milford, Massachusetts. The community was the Utopian community at Brook Earm in December of designed to put into effect Ballou's practical Christian val 1840, some might be less aware of his experience a year ues, which included "abhorrence of war, slavery, intemper later with another famous communitarian, Adin Ballou ance, licentiousness, covetousness, and worldly ambition in (1803-1890), the founder of the Hopedale Community. all their forms."' Bom in Cumberland, R.I., Ballou was raised in a strict About the time Ballou was drawing up his plans for the Calvinist household before his conversion to a more enthu Hopedale Community, he was also working the lecture cir siastic and fundamental "Christian Connection" faith. In cuit, promoting his various reforms, including communitar- 1821, he became a self-appointed preacher within that ianism. On February 4, 1841, he lectured on antislavery at group, but very soon came to doubt their doctrine of the Universalist Church in Concord. The following night he "Destmctionism," a belief in the "final doom of the im spoke on Non-resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Emerson penitent wicked." As a result, in 1822, he converted to the attended the latter gathering, and apparently was not im Universalist faith, which professed a belief in the uncon pressed. He reported tlie following to his brother William: ditional salvation of all souls. -

Hay Fever Holiday: Health, Leisure, and Place in Gilded-Age America

600 gregg mitman Hay Fever Holiday: Health, Leisure, and Place in Gilded-Age America GREGG MITMAN summary: By the 1880s hay fever (also called June Cold, Rose Cold, hay asthma, hay cold, or autumnal catarrh) had become the pride of America’s leisure class. In mid-August each year, thousands of sufferers fled to the White Mountains of New Hampshire, to the Adirondacks in upper New York State, to the shores of the Great Lakes, or to the Colorado plateau, hoping to escape the dreaded seasonal symptoms of watery eyes, flowing nose, sneezing fits, and attacks of asthma, which many regarded as the price of urban wealth and education. Through a focus on the White Mountains as America’s most fashionable hay fever resort in the late nineteenth century, this essay explores the embodied local geography of hay fever as a disease. The sufferers found in the White Mountains physical relief, but also a place whose history affirmed their social identity and shaped their relationship to the natural environment. And, they, in turn, became active agents in shaping the geography of place: in the very material relationships of daily life, in the social contours of the region, and in the symbolic space that nature inhabited. In the consumption of nature for health and pleasure, this article suggests, lies an important, yet relatively unexplored, source for understanding changing perceptions of environment and place and the impact of health on the local and regional transformation of the North American landscape. keywords: climatotherapy, hay fever, leisure, nature conservation, tourism, wilderness, place I owe special thanks to Martha V. -

Den Läsande Hjältinnan

Den läsande hjältinnan Kön, begär och intimitet i tre romaner av Fredrika Bremer ______ Camilla Wallin Bergström Ämne: Litteraturvetenskap Nivå: Master Poäng: 45 hp Ventilerad: VT 2018 Handledare: Sigrid Schottenius Cullhed Examinator: Otto Fischer Abstract: This thesis explores fictional representations of women’s reading practices in the early novels of Fredrika Bremer. I examine these in relation to the negotiations of reading habits in Sweden and Europe during the 1830’s, particularly pertaining to questions of gender, intimacy, desire, and corporeality. The material consists of three novels (The Family H***, The Neighbours and Home), in which the motif of women’s reading plays a significant part. In the four chapters of the thesis, I analyse key aspects of gender and reading in Bremer’s novels: 1) the popular stereotype of obsessive novel reading, and how this specific practice is portrayed in relation to the duties of a wife and mother, as well as to intimacy and secrecy; 2) representations of corrupted or illicit readers, whose reading practices disturbs the confines of nineteenth-century femininity; and 3) how these characters may challenge or bypass the restrictions of gender roles through fictional engagement. The thesis argues that Bremer’s representations of women’s reading are more complex and varied than has previously been recognized, and it reveals new aspects of these representations, such as the significance of intimacy with oneself and others in Bremer’s depictions of silent reading practices, and the transgressive power of feminine empathy. Keywords: Fredrika Bremer, history of reading, sexuality, gender, interiority, intimacy, empathy, the reading debate 2 Innehållsförteckning Inledning 4 Syfte och frågeställningar 6 Metod och material 6 Teoretiska utgångspunkter 11 Forskningsöversikt 16 Undersökningens disposition 18 1. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 56, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Fall 1995 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 56, No. 2 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 1995 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 56 (2) FALL 1995 CLAMSHELL BLUFF, CONCORD, MASSACHUSETTS: The Concord Shell Heap and Field at Clamshell Bluff: Introduction and History. Shirley Blancke 29 Clamshell Bluff: Artifact Analyses Shirley Blancke 35 Freshwater Bivalves of the Concord Shell Heap . Elinor F. Downs 55 Bone from Concord Shell Heap, Concord, Massachusetts Tonya Baroody Largy 64 Archaeological Turtle Bone Remains from Concord Shell Heap Anders G. J. Rhodin 71 Clamshell Bluff: Summary Notes Shirley Blancke and Elinor F. Downs 83 BriefNote to Contributors 34 Contributors 84 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P.O.Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Officers: Curtiss Hoffman, 58 Hilldale Rd., Ashland MA 01721 .. .. President Betsy McGrath, 9 Oak St., Middleboro MA 02346. ... V.ice President Thomas Doyle, P.O. Box 1708, North Eastham MA 02651 .... Clerk Irma Blinderman, 31 Buckley Rd., Worcester MA 01602 . ........... Treasurer Ruth Warfield, 13 Lee St., Worcester MA 01602 ... Museum Coordinator, Past President Elizabeth A. Little, 37 Conant Rd., Lincoln MA 01773 .... Bulletin Editor Lesley H. Sage, 33 West Rd., 2B, Orleans MA 02653 ..... Corresponding Secretary Trustees (Term expires 1997[*]; 1996 [+]): Kathleen S. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Thoreau: Desperate and Deliberate Lives

Thoreau: Desperate and Deliberate Lives One: Introduction 1. Who is Henry David Thoreau? (30 minutes) a. Short answer: A 19th century New England writer and practical philosopher who lived at Walden Pond b. OR show intro film (scroll down to Walden at Walden.org) c. OR longer answer: (small groups, brief research and sketch presentations, include credible sources and two to three images) i. Person: Who is HDT? ii. Place: Where is Walden Pond and what did he do? iii. Thing: What is his book, Walden, about, and what is its significance? iv. People: A brief overview of the Transcendentalists 2. Thoreau quotes (Share a short collection of HDT quotes— select a few or do a Thoreau quotes image search.) (20 minutes) a. Students choose one and write brief paragraph reflection, share and discuss some of these b. Tie quotes together—from this short collection, what can we deduce about T’s life and philosophy? c. Google list—JFK to Tolstoy, EO Wilson to MLK i. Remarkable breadth—social activists, politicians, writers, environmentalists 3. Introduce the living deliberately quote a. Share key quote from Walden: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” (Show sign image at house site) i. Thoughts, reactions, questions…. ii. What does it mean to ‘live deliberately’ and do we? 4. Homework: Read the section on building his house in Walden (four or five pages in the middle of “Economy”) Two: Thoreau’s House 5. -

Charles Sumner (1811–1874)

Charles Sumner (1811–1874) Charles Sumner, a U.S. senator from ith his large head, thick hair and muttonchops, and Massachusetts and a passionate aboli- broad torso, abolitionist Charles Sumner presented tionist, was born in Boston. After law school he spent time in Washington, D.C., where a powerful image. This likeness of Sumner by Walter he met with Chief Justice John Marshall and Ingalls resembles in several regards an 1860 “Impe- listened to Henry Clay debate in the Senate rial” photograph (24 x 20 inches) by Mathew Brady. Chamber. Unimpressed with the politics of The photograph, like the painting, shows Sumner facing left. His body Washington, he returned to Massachusetts, W where he practiced law, lectured at Har- is at a three-quarter angle so that the torso opens up, revealing an expanse vard Law School, and published in the of white waistcoat, watch fob, and folding eyeglasses suspended from American Jurist. Following a three-year study tour of Europe, Sumner resumed his a slender cord or chain. However, Ingalls repositioned the head into law practice with little enthusiasm. Then, profile and also placed the disproportionately short left thigh parallel in 1845, he was invited to make a public to the picture plane. The conflict of the planar head and thigh with the Independence Day speech in Boston. This event was a turning point in his career, angled torso is awkward and distracting. The profile head (with less and he soon became widely known as unruly hair than in the photograph) is, however, calm and pensive, and an eloquent orator. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

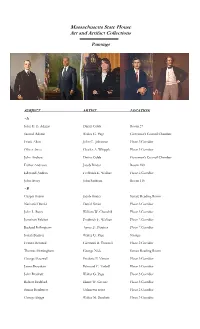

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson 1820-1872

lil p lip m mi: Ealpi) ^alUa emeraum* COMPLETE WORKS. Centenary EdittOH. 12 vols., crown 8vo. With Portraits, and copious notes by Ed- ward Waldo Emerson. Price per volume, $1.75. 1. Nature, Addresses, and Lectures. 3. Essays : First Series. 3. Essays : Second Series. 4. Representative Men. 5. English Traits. 6. Conduct of Life. 7. Society and Solitude. 8. Letters and Social Aims. 9. Poems, xo. Lectures and Biographical Sketches, 11. Miscellanies. 13. Natural History of Intellect, and other Papers. With a General Index to Emerson's Collected Works. Riverside Edition. With 2 Portraits. la vols., each, i2mo. gilt top, $1.75; the set, $31.00. Little Classic Edition. 13 vols. , in arrangement and coo- tents identical with Riverside Edition, except that vol. la is without index. Each, i8mo, $1.25 ; the set, $15 00. POEMS. Household Edition. With Portrait. lamo, $1.50} full gilt, $2.00. ESSAYS. First and Second Series. In Cambridge Classics. Crown 8vo, $1.00. NATURE, LECTURES, AND ADDRESSES, together with REPRESENTATIVE MEN. In Cambridge Classics. Crown 8vo, f i.oo. PARNASSUS. A collection of Poetry edited by Mr. Emer- son., Introductory Essay. Hoitsekold Edition. i2mo, 1^1.50, Holiday Edition. Svo, $3.00. EMERSON BIRTHDAY BOOK. With Portrait and Illus- trations. i8mo, $1.00. EMERSON CALENDAR BOOK. 32mo, parchment-paper, 35 cents. CORRESPONDENCE OF CARLYLE AND EMERSON. 834-1872. Edited by Charles Eliot Norton. 2 ols. crown Svo, gilt top, $4.00. Library Edition. 2 vols. i2mo, gilt top, S3.00. CORRESPONDENCE OF JOHN STERLING AND EMER- SON. Edited, with a sketch of Sterling's life, by Ed- ward Waldo Emerson.