President Andrew Johnson's Pottier & Stymus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the Styles and Techniques of French Master Carvers and Gilders

LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F SEPTEMBER 15, 2015–JANUARY 3, 2016 What makes a frame French? Discover the styles and techniques of French master carvers and gilders. This magnificent frame, a work of art in its own right, weighing 297 pounds, exemplifies French style under Louis XV (reigned 1723–1774). Fashioned by an unknown designer, perhaps after designs by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (French, 1695–1750), and several specialist craftsmen in Paris about 1740, it was commissioned by Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, a powerful French legal official, to accentuate his exceptionally large pastel portrait and its heavy sheet of protective glass. On this grand scale, the sweeping contours and luxuriously carved ornaments in the corners and at the center of each side achieve the thrilling effect of sculpture. At the top, a spectacular cartouche between festoons of flowers surmounted by a plume of foliage contains attributes symbolizing the fair judgment of the sitter: justice (represented by a scale and a book of laws) and prudence (a snake and a mirror). PA.205 The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F Frames are essential to the presentation of paintings. They protect the image and permit its attachment to the wall. Through the powerful combination of form and finish, frames profoundly enhance (or detract) from a painting’s visual impact. The early 1600s through the 1700s was a golden age for frame making in Paris during which functional surrounds for paintings became expressions of artistry, innovation, taste, and wealth. The primary stylistic trendsetter was the sovereign, whose desire for increas- ingly opulent forms of display spurred the creative Fig. -

State Historic Preservation Officer Certification the Evaluated Significance of This Property Within the State Is

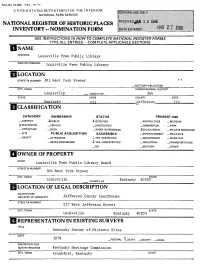

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC Louisville Free Public Library AND/OR COMMON Louisville Free public Library LOCATION STREET&NUMBER 301 West York Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN " . , " , CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Louisville . .VICINITY OF 3&4 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 llMll.'Jeff«r5»rvn 111 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT -XPUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS .^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS J-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -^TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Louisville Free Public Library Board STREET & NUMBER 301 West York Street STATE CITY, TOWN Louisville VICINITY OF Kentucky 40203 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, » REGISTRY OF DEEDS; ETC. Jefferson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 517 West Jefferson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Louisville Kentucky 40203 TITLE Kentucky Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1978 —FEDERAL <LsTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN Frankfort, Kentucky STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -

The Arts of Early Twentieth Century Dining Rooms: Arts and Crafts

THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY (Under the Direction of John C. Waters) ABSTRACT Within the preservation community, little is done to preserve the interiors of historic buildings. While many individuals are concerned with preserving our historic resources, they fail to look beyond the obvious—the exteriors of buildings. If efforts are not made to preserve interiors as well as exteriors, then many important resources will be lost. This thesis serves as a catalog of how to recreate and preserve an historic dining room of the early twentieth century in the Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco styles. INDEX WORDS: Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Dining Room, Dining Table, Dining Chair, Sideboard, China Cabinet, Cocktail Cabinet, Glass, Ceramics, Pottery, Silver, Metalworking, Textiles, Lighting, Historic Preservation, Interior Design, Interior Decoration, House Museum THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY B.S.F.C.S, The University of Georgia, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 Sue-anna Eliza Dowdy All Rights Reserved THE ARTS OF EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DINING ROOMS: ARTS AND CRAFTS, ART NOUVEAU, AND ART DECO by SUE-ANNA ELIZA DOWDY Major Professor: John C. Waters Committee: Wayde Brown Karen Leonas Melanie Couch Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May, 2005 DEDICATION To My Mother. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

Introduction

1 INTRODUCTION “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.” Charles Darwin. This study is a retelling of a story of mistaken identity that has persisted in the annals of decorative arts for almost a century. The subjects are three examples of exceptional curvilinear chairs made out of exotic wood and forged in the great change and cultural upheaval in the first third of the nineteenth century in the United States. The form of these chairs has been assumed to belong to a later generation, but the analysis in the pages that follow attempt to restore their birthright as an earlier transitional step in the evolution of American furniture. These three curvilinear chairs – significantly different in design from earlier nineteenth-century forms – are remarkable as they exemplify how exquisite the curvilinear form could be in its early stages. Despite the fact that these chairs are an important link in furniture history, they have not been fully appreciated by either scholars or connoisseurs. Although there were many curvilinear chairs produced in the period, this study will focus on three remarkably similar examples: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s side chair (68.202.1); the Merchant’s House Museum’s twelve side chairs (2002.2012.1-12); and, finally a set of sixteen owned by a descendent of the New York cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe (Cat. 46 in An Elegant Assortment: The Furniture of Duncan Phyfe and His Contemporaries, 1800-1840).1 It has been suggested this set was 1 The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s curvilinear side chair (68.202.1) is described on website: “As craftsmen transitioned from the Early to the Late Grecian style (the latter is also referred to as the Grecian Plain Style), they began to incorporate more curvilinear shapes and new 2 made by Duncan Phyfe for his daughter Eliza Phyfe Vail. -

Palladio's Influence in America

Palladio’s Influence In America Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2008 marks the 500th anniversary of Palladio’s birth. We might ask why Americans should consider this to be a cause for celebration. Why should we be concerned about an Italian architect who lived so long ago and far away? As we shall see, however, this architect, whom the average American has never heard of, has had a profound impact on the architectural image of our country, even the city of Baltimore. But before we investigate his influence we should briefly explain what Palladio’s career involved. Palladio, of course, designed many outstanding buildings, but until the twentieth century few Americans ever saw any of Palladio’s works firsthand. From our standpoint, Palladio’s most important achievement was writing about architecture. His seminal publication, I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura or The Four Books on Architecture, was perhaps the most influential treatise on architecture ever written. Much of the material in that work was the result of Palladio’s extensive study of the ruins of ancient Roman buildings. This effort was part of the Italian Renaissance movement: the rediscovery of the civilization of ancient Rome—its arts, literature, science, and architecture. Palladio was by no means the only architect of his time to undertake such a study and produce a publication about it. Nevertheless, Palladio’s drawings and text were far more engaging, comprehendible, informative, and useful than similar efforts by contemporaries. As with most Renaissance-period architectural treatises, Palladio illustrated and described how to delineate and construct the five orders—the five principal types of ancient columns and their entablatures. -

Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19Th C

anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19th C FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:73cm Width:60cm Depth:40cm Price:2250€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is a beautiful small antique English Empire Gonçalo Alves console with integral writing slide and pen drawer, circa 1820 in date. This dual purpose table has a drawer above a pair of elegant tapering columns with gilded mounts to the top and bottom, behind them is a pair of rectangular columns framing a framed fabric slide that lifts up when required. This screen serves as a modesty / privacy screen. This piece has a single drawer with a writing slide with its original olive green leather writing surface over a pen drawer that can be pulled out from the side of the drawer whilst the writing surface is in use. This gorgeous console table will instantly enhance the style of one special room in your home and is sure to receive the maximum amount of attention wherever it is placed. Condition: In excellent condition having been beautifully restored in our workshops, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 73 x Width 60 x Depth 40 Dimensions in inches: Height 28.7 x Width 23.6 x Depth 15.7 Empire style, is an early-19th-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts followed in Europe and America until around 1830. 1 / 3 anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com The style originated in and takes its name from the rule of Napoleon I in the First French Empire, where it was intended to idealize Napoleon's leadership and the French state. -

How to Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture

How To Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples Of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture frenchstyleauthority.com /archives/how-to-paint-black-furniture-a-dozen-examples-of-exceptional-black- painted-furniture Black furniture has been one of the most popular furniture paint colors in history, and a close second is white. Today, no other color comes close to these two basic colors which always seem to be a public favorite. No matter what the style is, black paint has been fashionable choice for French furniture,and also for primitive early American, regency and modern furniture. While the color of the furniture the same, the surrounds of these distinct styles are polar opposite requiring a different finish application. Early American furniture is often shown with distressing around the edges. Wear and tear is found surrounding the feet of the furniture, and commonly in the areas around the handles, and corners of the cabinets or commodes. It is common to see undertones of a different shade of paint. Red, burnt orange are common colors seen under furniture pieces. Furniture made from different woods, are often painted a color similar to wood color to disguise the fact that it was made from various woods. Paint during this time was quite thin, making it easily naturally distressed over time. – Black-painted Queen Anne Tilt-top Birdcage Tea Table $3,000 Connecticut, early 18th century, early surface of black paint over earlier red Joseph Spinale Furniture is one of the best examples to look at for painting ideas for early American furniture. This primitive farmhouse kitchen cupboard is heavily distressed with black paint. -

2017 Navy Football Media Guide Was Prepared to Assist the Media in Its Coverage of Navy Football

2017 NAVY FOOTBALL SCHEDULES 2017 Schedule Date Opponent Time Series Record TV Location Sept. 1 at Florida Atlantic 8:00 PM Navy leads, 1-0 ESPNU Boca Raton, Fla. Sept. 9 Tulane + 3:30 PM Navy leads, 12-8-1 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Sept. 23 Cincinnati + 3:30 PM Navy leads, 2-0 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Sept. 30 at Tulsa + TBA Navy leads, 3-1 TBA Tulsa, Okla. Oct. 7 Air Force 3:30 PM Air Force leads, 29-20 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Oct. 14 at Memphis + TBA Navy leads, 2-0 TBA Memphis, Tenn. Oct. 21 UCF + 3:30 PM First Meeting CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Nov. 3 at Temple + 7:30 or 8:00 PM Series tied, 6-6 ESPN Philadelphia, Pa. Nov. 11 SMU + 3:30 PM Navy leads, 11-7 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Nov. 18 at Notre Dame 3:30 PM Notre Dame leads, 75-13-1 NBC South Bend, Ind. Nov. 24 at Houston + TBA Houston leads, 2-1 ABC or ESPN Family of Networks Houston, Texas Dec. 2 AAC Championship Game TBA N/A ABC or ESPN TBA Dec. 9 vs. Army 3:00 PM Navy leads, 60-50-7 CBS Philadelphia, Pa. + American Athletic Conference game All Times Eastern 2016 In Review Date Opponent Result Attendance TV Location Sept. 3 Fordham Won, 52-16 28,238 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Sept. 10 UConn + Won, 28-24 31,501 CBS Sports Network Annapolis, Md. Sept. 17 at Tulane + Won, 21-14 21,503 American Sports Network/ESPN3 New Orleans, La. -

American Factory-Mad

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality o f the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. I f copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Congressional Record-House. 2783

1910. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 2783 PENNSYLVA.NIA. Henry A. Perrin, at Monroe, Iowa. 0. William Beales to be postmaster at Gettysburg, Pa., in Lucy B. Smith, at Sioux Rapids, Iowa. place of William B. Mcilhenny. Incumbent's commission ex MINNESOTA. pired February 22, 1910. Samuel Y. Gordon, at Brown Valley, Minn. Arthur E. Kurtz to be postmaster at Connellsville, Pa., in Thomas L. Jones, at Warroad, Minn. place of Clark Collins. Incumbent's commission expires March 22, 1910. MONTANA. David Russell to be postmaster at Renovo, Pa., in place of James H. Powell, at Virginia City, Mont. David Russell. rneumbent's commission expires April 24, 1910. NEBRASKA. TENNESSEE. Albert H. Hollingsworth, at Beatrice, Nebr. Harry Swaney to be postmaster at Galla tin, Tenn., in place William K. Sargent, at Elmwood, Nebr. of Harry Swaney. Incumbent's commission expires March 21, Lewis M. Short, at Ainsworth, Nebr. 1910. George W. Williams, at Albion, Nebr. TEXAS. NEW YORK. W. P. Park to be postmaster at Port Arthur, Tex., in place of George H. Brown, at Kinderhook, N. Y. Clark E. Dodge. Incumbent's commission expired April 27, John Dwyer, at Hudson Falls (late Sandy Hill),. N. Y. 1908. Melvin J. Esmay, at Schenevus, N. Y. Ellwood Valentine, at Glen Cove, N. Y. CONFIR1\IATIONS. PENNSYLVANIA. C. William Beales, at Gettysburg, Pa. Executive 1wminations confirmed 011 the Senate March S, 1910. Arthur E. Kurtz, at Connellsville, Pa. (Calendar day, Mwrch 5, 1910.) Nathan Tanner, at Lansford, Pa~ COLLECTOR OF CuSTOMS. SOUTH DAKOTA, Frederick 0. Murray to be collector of customs for the district Frank D. -

University of Nashville, Literary Department Building HABS No. TN-18 (Now Children's Museum) O 724 Second Avenue, North M Nashville Davidson County HAB'j Tennessee

University of Nashville, Literary Department Building HABS No. TN-18 (now Children's Museum) o 724 Second Avenue, North m Nashville Davidson County HAB'j Tennessee PHOTOGRAPHS § HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey National Architectural and Engineering Record National Park Service 1 Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 &S.TENN. fl-NA^H. ISA I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. TM-18 UNIVERSITY OF NASHVILLE, LITERARY DEPARTMENT BUILDING (now Children7s Museum) > v. >- Location: 724 Second Avenue, South, Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee Present Owner: Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County Significant: Begun in 1853 by Major Adolphus Herman, one of Nashville's pioneer architects, the main building for the University of Nashville inaugurated the rich tradition of collegiate Gothic architecture in Nashville. Housing the Literary Department of the University, the building was one of the first permanent structures of higher learning in the city. The University of Nashville was one of the pioneer educa- tional institutions in the State of Tennessee, its ancestry antedating Tennessee statehood. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History 1. Date of Erection: The cornerstone was laid on April 7, 1853. The completed building was dedicated on October 4, 1854. 2' Architect; Adolphus Heiman. However, he was not the architect first selected by the Board of Trustees, their initial choice having been the eminent Greek Revivalist Isaiah Rogers, WUJ had moved from Boston to Cincinnati. On March 4, 1852, the Building Committee of the Board of Trustees for the University of Nash- ville reported that they had engaged the services of Isaiah Rogers, then of Cincinnati, as architect.