French Furniture Under Louis Xiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

French Furniture in the Middle Ages and Under Louis Xiii French Furniture

«IW'T--W!*W'. r,-.,»lk«»«».^*WIWP^5'5.^ Mi|i#|MMiMii^^ B0B€RT>4OlM€S FOK MAMV YEARSATEACHER iH THIS COLLECE.0nP^-.Syi THIS Bffl)K.lSONE9FA)vlUMB9? FROMTJ4E UBJ?AK.y9^JvLR>lOiMES PIJESENTED T01}4EQMTAglO CDltEGE 9^A^ DY HIS RELA.TIVES / LITTLE ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ON OLD FRENCH FURNITURE I. FRENCH FURNITURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES AND UNDER LOUIS XIII FRENCH FURNITURE I. French Furniture in the Middle Ages and under Louis XIII II. French Furniture under Louis XIV III. French Furniture under Loujs XV IV. French Furniture under Louis XVI AND THE Empire ENGLISH FURNITURE (Previously published) I. English Furniture under the Tudors and Stuarts II. English Furniture of the Queen Anne Period III. English Furniture of the Chippen- dale Period IV. English Furniture of the Sheraton Period Each volume profusely illustrated with full-page reproductions and coloured frontispieces Crown SvOf Cloth, price 4s. 6d. net LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. Cupboard in Two Parts (Middle of the XVIth Century) LITTLE ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ON OLD FRENCH FURNITURE I FRENCH FURNITURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES AND UNDER LOUIS XIII BY ROGER DE FELICE Translated by F. M. ATKINSON LONDON MCMXXIII WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD. / OS^'i S5 First published, 1923 Printed in Great Britain hy Woods & Sons, Ltd,f London, N. i. INTRODUCTION A CONSECUTIVE and complete history of French furniture—complete in that it should not leave out the furniture used by the lower middle classes, the artisans and the peasants —remains still to be written ; and the four little books of this series are far from claiming to fill such a gap. -

JC-Catalogue-Cabinetry.Pdf

jonathan charles fine furniture • cabinetry & beds catalogue • volume 1 volume • furniture fine cabinetry • & beds catalogue jonathan charles USA & CANADA 516 Paul Street, P.O. Box 672 Rocky Mount, NC.27802, United States t 001-252-446-3266 f 001-252-977-6669 [email protected] HIGH POINT SHOWROOM chests of drawers • bookcases, bookshelves & étagères • cabinets • beds 200 North Hamilton Building 350 Fred Alexander Place High Point, NC.27260, United States t 001-336-889-6401 UK & EUROPE Unit 6c, Shortwood Business Park Dearne Valley Park Way, Hoyland South Yorkshire, S74 9LH, United Kingdom t +44 (0)1226 741 811 & f +44 (0)1226 744 905 Cabinetry Beds [email protected] j o n a t h a n c h a r l e s . c o m printed in china It’s all in the detail... CABINETRY & BEDS JONATHAN CHARLES CABINETRY & BEDS CATALOGUE VOL.1 CHESTS OF DRAWERS 07 - 46 BOOKCASES, BOOKSHELVES... 47 - 68 CABINETS 69 - 155 BEDS 156 - 164 JONATHANCHARLES.COM CABINETRY & BEDS Jonathan Charles Fine Furniture is recognised as a top designer and manufacturer of classic and period style furniture. With English and French historical designs as its starting point, the company not only creates faithful reproductions of antiques, but also uses its wealth of experience to create exceptional new furniture collections – all incorporating a repertoire of time- honoured skills and techniques that the artisans at Jonathan Charles have learned to perfect. Jonathan Charles Fine Furniture was established by Englishman Jonathan Sowter, who is both a trained cabinet maker and teacher. Still deeply involved in the design of the furniture, as well as the direction of the business, Jonathan oversees a skilled team of managers and craftspeople who make fine furniture for discerning customers around the world. -

Discover the Styles and Techniques of French Master Carvers and Gilders

LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F SEPTEMBER 15, 2015–JANUARY 3, 2016 What makes a frame French? Discover the styles and techniques of French master carvers and gilders. This magnificent frame, a work of art in its own right, weighing 297 pounds, exemplifies French style under Louis XV (reigned 1723–1774). Fashioned by an unknown designer, perhaps after designs by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (French, 1695–1750), and several specialist craftsmen in Paris about 1740, it was commissioned by Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, a powerful French legal official, to accentuate his exceptionally large pastel portrait and its heavy sheet of protective glass. On this grand scale, the sweeping contours and luxuriously carved ornaments in the corners and at the center of each side achieve the thrilling effect of sculpture. At the top, a spectacular cartouche between festoons of flowers surmounted by a plume of foliage contains attributes symbolizing the fair judgment of the sitter: justice (represented by a scale and a book of laws) and prudence (a snake and a mirror). PA.205 The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F Frames are essential to the presentation of paintings. They protect the image and permit its attachment to the wall. Through the powerful combination of form and finish, frames profoundly enhance (or detract) from a painting’s visual impact. The early 1600s through the 1700s was a golden age for frame making in Paris during which functional surrounds for paintings became expressions of artistry, innovation, taste, and wealth. The primary stylistic trendsetter was the sovereign, whose desire for increas- ingly opulent forms of display spurred the creative Fig. -

State Historic Preservation Officer Certification the Evaluated Significance of This Property Within the State Is

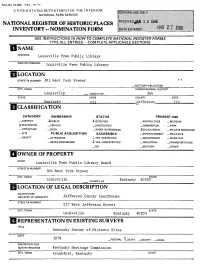

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC Louisville Free Public Library AND/OR COMMON Louisville Free public Library LOCATION STREET&NUMBER 301 West York Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN " . , " , CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Louisville . .VICINITY OF 3&4 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 llMll.'Jeff«r5»rvn 111 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT -XPUBLIC X.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS .^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS J-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL -^TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Louisville Free Public Library Board STREET & NUMBER 301 West York Street STATE CITY, TOWN Louisville VICINITY OF Kentucky 40203 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, » REGISTRY OF DEEDS; ETC. Jefferson County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 517 West Jefferson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Louisville Kentucky 40203 TITLE Kentucky Survey of Historic Sites DATE 1978 —FEDERAL <LsTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN Frankfort, Kentucky STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -

The Furnishing of the Neues Schlob Pappenheim

The Furnishing of the Neues SchloB Pappenheim By Julie Grafin von und zu Egloffstein [Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow] Christie’s Education London Master’s Programme October 2001 © Julie Grafin v. u. zu Egloffstein ProQuest Number: 13818852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818852 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 l a s g o w \ £5 OG Abstract The Neues SchloB in Pappenheim commissioned by Carl Theodor Pappenheim is probably one of the finest examples of neo-classical interior design in Germany retaining a large amount of original furniture. Through his commissions he did not only build a house and furnish it, but also erected a monument of the history of his family. By comparing parts of the furnishing of the Neues SchloB with contemporary objects which are partly in the house it is evident that the majority of these are influenced by the Empire style. Although this era is known under the name Biedermeier, its source of style and decoration is clearly Empire. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field

CHAPTER 11 The Grottesche Part 1. Fragment to Field We touched on the grottesche as a mode of aggregating decorative fragments into structures which could display the artist’s mastery of design and imagi- native invention.1 The grottesche show the far-reaching transformation which had occurred in the conception and handling of ornament, with the exaltation of antiquity and the growth of ideas of artistic style, fed by a confluence of rhe- torical and Aristotelian thought.2 They exhibit a decorative style which spreads through painted façades, church and palace decoration, frames, furnishings, intermediary spaces and areas of ‘licence’ such as gardens.3 Such proliferation shows the flexibility of candelabra, peopled acanthus or arabesque ornament, which can be readily adapted to various shapes and registers; the grottesche also illustrate the kind of ornament which flourished under printing. With their lack of narrative, end or occasion, they can be used throughout a context, and so achieve a unifying decorative mode. In this ease of application lies a reason for their prolific success as the characteristic form of Renaissance ornament, and their centrality to later historicist readings of ornament as period style. This appears in their success in Neo-Renaissance style and nineteenth century 1 The extant drawings of antique ornament by Giuliano da Sangallo, Amico Aspertini, Jacopo Ripanda, Bambaia and the artists of the Codex Escurialensis are contemporary with—or reflect—the exploration of the Domus Aurea. On the influence of the Domus Aurea in the formation of the grottesche, see Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la Formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: Warburg Institute, Leiden: Brill, 1969); idem, “Ghirlandaio et l’antique”, Bulletin de l’Institut Historique Belge de Rome 39 (1962), 419– 55; idem, Le Logge di Raffaello: Maestro e bottega di fronte all’antica (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1977, 2nd ed. -

Auction - Quarterly Fine Art - Day 2 Featuring Antique Picture Frames, Asian Arts, Works of Art and Fine Furniture 01/07/2015 10:00 AM GMT

Auction - Quarterly Fine Art - Day 2 featuring Antique Picture Frames, Asian Arts, Works of Art and Fine Furniture 01/07/2015 10:00 AM GMT Lot Title/Description Lot Title/Description 750 A Dutch Nutwood Cassetta Frame, early 19th century, with cavetto and 760 A Dutch Nutwood Bolection Frame, 17th century, with cavetto and ogee sight, the frieze with pewter inlaid stringing, quarter beaded course reeded sight, reverse ovolo, and cushion moulded back edge, and wedge front edge, 42.9x34.4cm 41.5x33.5cm A Dutch Nutwood Cassetta Frame, early 19th century, with cavetto and A Dutch Nutwood Bolection Frame, 17th century, with cavetto and ogee sight, the frieze with pewter inlaid stringing, quarter beaded course reeded sight, reverse ovolo, and cushion moulded back edge, and wedge front edge, 42.9x34.4cm 41.5x33.5cm Est. 300 - 400 Est. 800 - 1,200 751 A Florentine Carved, Gilded and Pierced Frame, 18th century, with 761 A Pair of Dutch Nutwood Frames, early 19th century, each with raked cavetto sight, hazzle, with boldly scrolling leaf top and back edges, marquetry and cavetto sight, plain hollow and top knull, 50.5x70.2cm., 42.8x35cm ea., (2) A Florentine Carved, Gilded and Pierced Frame, 18th century, with A Pair of Dutch Nutwood Frames, early 19th century, each with raked cavetto sight, hazzle, with boldly scrolling leaf top and back edges, marquetry and cavetto sight, plain hollow and top knull, 50.5x70.2cm., 42.8x35cm ea., (2) Est. 600 - 800 Est. 400 - 600 752 Two Near Matched Carved, Parcel Gilded and Ebonised Frames, 19th 762 An Gilt Composition -

Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19Th C

anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com Antique English Empire Console Writing Side Table 19th C FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 19° secolo - 1800 Regent Antiques London Style: Altri stili +44 2088099605 447836294074 Height:73cm Width:60cm Depth:40cm Price:2250€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: This is a beautiful small antique English Empire Gonçalo Alves console with integral writing slide and pen drawer, circa 1820 in date. This dual purpose table has a drawer above a pair of elegant tapering columns with gilded mounts to the top and bottom, behind them is a pair of rectangular columns framing a framed fabric slide that lifts up when required. This screen serves as a modesty / privacy screen. This piece has a single drawer with a writing slide with its original olive green leather writing surface over a pen drawer that can be pulled out from the side of the drawer whilst the writing surface is in use. This gorgeous console table will instantly enhance the style of one special room in your home and is sure to receive the maximum amount of attention wherever it is placed. Condition: In excellent condition having been beautifully restored in our workshops, please see photos for confirmation. Dimensions in cm: Height 73 x Width 60 x Depth 40 Dimensions in inches: Height 28.7 x Width 23.6 x Depth 15.7 Empire style, is an early-19th-century design movement in architecture, furniture, other decorative arts, and the visual arts followed in Europe and America until around 1830. 1 / 3 anticSwiss 02/10/2021 08:28:16 http://www.anticswiss.com The style originated in and takes its name from the rule of Napoleon I in the First French Empire, where it was intended to idealize Napoleon's leadership and the French state. -

Stowe: a Description of the Magnificent House and Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple

www.e-rara.ch Stowe: a description of the magnificent house and gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple ... Seeley, Robert Benton Buckingham, 1780 ETH-Bibliothek Zürich Shelf Mark: Rar 6719 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-830 A Description of the House. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work.