Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces As Windows Into Experience: the Spiraled Conductor and Star Wheel Interrupter of Charles Grafton Page

| Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces as Windows into Experience | 123 | Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces as Windows into Experience: The Spiraled Conductor and Star Wheel Interrupter of Charles Grafton Page Elizabeth CAVICCHI a T Abstract When battery current flowing in his homemade spiraled conductor switched off, nineteenth century experimenter Charles Grafton Page saw sparks and felt shocks, even in parts of the spiral where no current passed. Reproducing his experiment today is improvisational: an oscilloscope replaces Page’s body; a copper star spinning through galinstan substitutes for Barlow’s wheel interrupter. Green and purple flashes accompanied my spinning wheel. Unlike what Page’s shocks showed, induced voltages probed across my spiral’s wider spans were variable, precipitating extensive explorations of its resonant fre - quencies. Redoing historical experiments extends our experience, fostering new observations about natural phenomena and experimental development. Keywords: electromagnetic induction, historical replication, Charles Grafton Page, exploratory learning, spiral, Barlow wheel, galinstan, autotransformer T Introduction real? Facing wires and wiggling magnetic needles firsthand, while trying to make sense of it, deepens Historical experiments come to us in fragments: our perspective; we become confused and curious handwritten data, published reports, and often non - (Cavicchi 2003). Redoing an experiment is not just a functioning apparatus. A further carry-over may per - check on facts, dates, whether Oersted’s needle went sist in ideas, procedures, materials and inventions east or west. It gives us access to experience congru - bearing imprints of the prior work. All these are clues ous with the past: “’to know an experimenter, you to something both more transitory and more coher - should replicate her study’” (Kurz 2001, p. -

The Limitless Self: Desire and Transgression in Jeanette Winterson’S Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and Written on the Body

The Limitless Self: Desire and Transgression in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and Written on the Body TREBALL DE RECERCA Francesca Castaño Méndez MÀSTER: Construcció I Representació d’Identitats Culturals. ESPECIALITAT: Estudis de parla anglesa. TUTORIA: Gemma López i Ana Moya TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARIES: “Only by imagining what we might be can we become more than we are”……………………………..............................1 CHAPTER 1: “God owns heaven but He craves the earth: The Quest for the Self in Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit”……..…9 1.1: “Like most people I lived for a long time with my mother and father”……….…11 1.2: “Why do you want me to go? I asked the night before”…………………….…...18 1.3: “The heathen were a daily household preoccupation”……………………….…..21 1.4: “It was spring, the ground still had traces of snow, and I was about to be married”……………………………...................................................................23 1.5: “Time is a great deadener. People forget, get bored, grow old, go away”….……26 1.6: “That walls should fall is the consequence of blowing your own trumpet”……..27 1.7: “It all seemed to hinge around the fact that I loved the wrong sort of people”……………………………...................................................................30 1.8: “It is not possible to change anything until you understand the substance you wish to change”……………………………......................................................32 CHAPTER 2: “It’s the clichés that cause the trouble: Love and loss in Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body”…………………………….....36 2.1: “Why is the measure of love loss?”…………………………...............................40 2.2: “Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights: the accumulations of a lifetime gather there”..…………………………................50 2.3: “Love is worth it”……………………………......................................................53 CONCLUSIONS: “I’m telling you stories. -

Page References in Italics Refer to Illustrations

INDEX Abattoir Company (Jersey Agassiz , Louis , 121, 435 office of the Supervising PAGEREFERENCES City , N .J.), 541 Airlie , Earl of , 156 - 157 Architect , 437- IN ITALICSREFER TO Abbey , Edwin Austin , Albany Capitol . SeeNew 438 ILLUSTRATIONS. 69 York State Capitol consolidation of , with Academie des Beaux - Albert (Prince Consort of Western Association , Arts (Paris ), 29, 35 England), 394 328 Hunt as member of , Albert Edward (Prince of conventions of 324 , 433 , 435 Wales ), 125 first (1867), 169 Academie Royale d' ArchitectureAldrich , Thomas Bailey, second (1868), 169 (Paris), 28, 95 third (1869), 169 29 , 108 - 109 Alexander II (Czar of ninth (1875), 252, 508 Academie Royale de Russia ), 159, 160 tenth (1876), 255- 256 Peinture et de Alexandria , Egypt , 51 twenty -second (1888), 327 Sculpture (Paris ), 28, All Souls ' Church 29 (Biltmore Village , twenty -third (1889), 327 - 329 Academy of Music Asheville , N .C .), (N .Y . C.), 539 454 - 455 , 548 twenty -fourth (1890), 329 - 330 Adams , Charles Francis , Aliard , Jules , et Fils , 513, 157 523 twenty -fifth (1891), 330 - 331 Adams , Mrs . Charles Allen Library (Pittsfield , Francis , 157 Mass .), 542 twenty -ninth (1895), 453 Adams , Henry , 265, 411 Alma - Tadema , Sir Adams , Mrs . John Lawrence , 295 , 323 early history of , 112- 117 Quincy , 8 Amboise , Chateau of , 49 Adams , Marian Hooper American Academy in first annual reception of (Mrs . Henry Adams ), Rome (1866), 168 265 background of, 438- 439 founding of , 110- 111, Adelbert College (Cleveland founding of , -

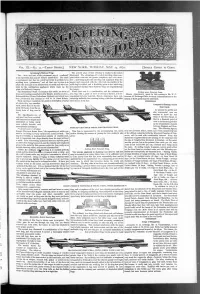

The Engineering and Mining Journal 1870-05-24

:.VPY y..T»0 VoL. IX.—No. 2 1.—Third Series.] NEW YORK, TUESDAY, MAY 24, 1870. [Single Copies 10 Cents. Armstrong's Railroad Frog. The genenil plau of this crossing is similar to the others ' The “wear and tear of the permanent way of a railroad” illustrated. The advantages of a rolled steel frog, when com¬ is an expression that may be termed paradoxical. The track pared with a cast one, are greater toughness and even struc¬ or permanent way has too much hard work to perform to be ture ; and being made with one wing rail separated from the anything near “ permanent,” and all that can be done is to tongue and connected with the other rail, the rigidity of the adopt the best and most durable form of metal and other ma¬ solid frog is avoided, and a flexibility given to the whole frog terial for the multifarious appliances which make up the not possessed by that where both the wings are separated from plant of a Railroad Company. the tongue. The illustrations which accompany this article are those of j Where first cost is a consideration, and the ordinary cast Section near Point of Frog, frogs and crossings manufactured by Messrs. Armstrong & Co., : iron frog with a plate of steel riveted on to its face, is to be Messrs. Armstrong’s agent in this country is Mr. W. C. Brinsworth Steel Works, Rotherham, England, and which have | superseded by better material, Messrs. Armstrong have con- Oastleb, 43 Exchange Place, to whom communications on the been patented in this country as well as in Great Britain. -

A Chronological History of Electrical Development from 600 B.C

From the collection of the n z m o PreTinger JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 / A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF ELECTRICAL DEVELOPMENT FROM 600 B.C. PRICE $2.00 NATIONAL ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURERS ASSOCIATION 155 EAST 44th STREET NEW YORK 17, N. Y. Copyright 1946 National Electrical Manufacturers Association Printed in U. S. A. Excerpts from this book may be used without permission PREFACE presenting this Electrical Chronology, the National Elec- JNtrical Manufacturers Association, which has undertaken its compilation, has exercised all possible care in obtaining the data included. Basic sources of information have been search- ed; where possible, those in a position to know have been con- sulted; the works of others, who had a part in developments referred to in this Chronology, and who are now deceased, have been examined. There may be some discrepancies as to dates and data because it has been impossible to obtain unchallenged record of the per- son to whom should go the credit. In cases where there are several claimants every effort has been made to list all of them. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association accepts no responsibility as being a party to supporting the claims of any person, persons or organizations who may disagree with any of the dates, data or any other information forming a part of the Chronology, and leaves it to the reader to decide for him- self on those matters which may be controversial. No compilation of this kind is ever entirely complete or final and is always subject to revisions and additions. It should be understood that the Chronology consists only of basic data from which have stemmed many other electrical developments and uses. -

National Register of Historic Places Received FEB 2 L984 Inventory

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received FEB 2 l984 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic Indianapolis News Building and or common Goodman Jewelers Building 2. Location street & number 30 w - Washington Sti N/A not for publication Indianapolis city, town N/A vicinity of Indiana 018 Marion 097 state code county code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district rpublic X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied X commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military Other: 4. Owner of Property name Goodman Jewelers, Inc. street & number 30 W. Washington Street city, town Indianapolis N/A vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Marion County Recorder Rm. 721-41 City-County Building street & number 200 E. Washington St. city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Survey Report for Indianapolis/Marion County title ______ (See continuation Sheet) has this property been determined eligible? _X-yes no date September 21, 1977 federal state county X local Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission, depository for survey records R00m 1821, City-County Building, 200 E. Washington St. city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 46204 7. -

Induction Coils A

7/25/2018 Induction Coil Induction Coils A. The Original Induction Coils The original induction coil was invented in 1836 by Nicholas Callan (1799-1864), a priest and the professor of natural philosophy at St. Patrick's College at Maynooth, County Kildare, Ireland. The basis for the coil was his large electromagnet with primary and secondary windings on the extremities of the U-shaped iron core. The primary circuit was interrupted (to get the required alternating current) by the mechanical Repeater that Callan designed. Callan's Great Induction Coil (left below) was left unfinished at Callan's death. The three secondary coils contain a total of 150,000 feet of fine iron wire. The primary coil is made of copper tape, wound around a core of iron wires. At the right below is the (incomplete) mechanism of interrupting the primary current. This apparatus, along with a similar one made by Callan which has only one secondary coil, is on display at the St. Patrick's College museum. The museum at St. Patrick's College contains parts of other early induction coils by Nicholas Callan. At the right are two long primary coils, and four toroidal secondary coils. The latter were insulated with a mixture of melted rosin and beeswax. Callan found that he could insulate 8000 ft of iron wire, 0.03 in. in diameter, per hour by passing it through this mixture and allowing it to harden on the wire, all in a continuous process. Independent of Callan, the American electrical inventor Charles Grafton Page (1812-1868) developed an induction coil in 1836. -

Origin of the Electric Motor

Origin of the Electric Motor JOSEPH C. MIGHALOWICZ MEMBER AIEE HE DAY that man Had it not been for the efforts of men like 1821—Michael Faraday dem- T molded the first wheel Davenport, De Jacobi, and Page, the benefits onstrated for the first time the from the sledlike skids of his of the electric motor would not be enjoyed possibility of motion by electro- magnetic means with the move- primitive wagon should be today. It is the purpose of this article to trace ment of a magnetic needle in a one of great commemoration, briefly the early history of the science of electro- field of force. had not its identity been lost motion and, in particular, to bring to light and 1829—-Joseph Henry, a teacher in the passing of time. Not to honor the inventor of the electric motor. of physics at the Albany Academy unlike the wheel and prob- in New York, constructed an elec- ably second only to the wheel, tromagnetic oscillating motor but considered it only a "philosophical the electric motor has been a toy." great benefactor to man and its history, too, slowly is 1833—Joseph Saxton, an American inventor, exhibited a magneto- being forgotten. Today, we hear very little, if anything, about Thomas Figure 1. Thomas Davenport, the blacksmith who invented the electric Davenport, inven- motor; or about De Jacobi, who propelled the first boat tor of the electric by means of an electric motor; or of Charles Page who motor successfully carried passengers on the first practical electric railway. Had it not been for the efforts of these men and others like them, the benefits of the electric motor probably would not be enjoyed today. -

Middleborough-1912.Pdf (8.337Mb)

•* 0X 4? * ** ; S' v* i'" j *«8b& /> <-*• /‘IC'Vy *V* ••lBSSKi : iSSryv ANNUAL REPORT of the TOWN OFFICERS of Middleboro, Mass. for the YEAR 1912 s' . I ANNUAL REPORT of the TOWN OFFICERS of Middleboro, Mass. for the YEAR 1912 3 TOWN OFFICERS, 1912. Town Clerk. ALBERT A. THOMAS Term expires 1915 Treasurer and Collector. ALBERT A. THOMAS Selectmen. CORNELIUS H. LEONARD Term expires 1913 CHARLES N. ATWOOD 44 “ 1914 WILLIAM M. HASKINS 44 “ 1915 Assessors. ALLERTON THOMPSON Term expires 1913 ALBERT T. SAVERY “ 44 1914 EDWIN F. WITHAM 44 44 1915 Overseers of the Poor. CHARLES M. THATCHER Term expires 1913 EDWIN F. WITHAM 44 11 1914 CHARLES W. KINGMAN 44 44 1915 School Committee. CHARLES S. TINKHAM Term expires 1913 E. T. PEIRCE JENKS “ 44 1913 GRANVILLE L. TILLSON 44 44 1914 LOUIS H. CARR “ 44 1914 GEORGE W. STETSON 44 44 1915 THEODORE N. WOOD 44 44 1915 Superintendent of Schools. CHARLES H. BATES 4 Municipal Light Board. WILKES H. F. PETTEE Term expires 1913 WILLIAM A. ANDREWS 44 “ 1914 HARLAS L. CUSHMAN 44 “ 1915 Board of Health. JOHN H. WHEELER Term expires 1913 BERT J. ALLAN 44 “ 1914 JAMES H. BURKHEAD, M. D. 44 44 1915 Constables. F. HERBERT BATCHELDER E. KIMBALL HARRISON FRANK W. HASTAY SAMUEL S. LOVELL HARRY F. SNOW FRED C. SPARROW HARRY W. SWIFT ICHABOD B. THOMAS Superintendent of Streets. WILLIAM H. CONNOR. Registrars of Voters. WILLIAM J. COUGHLIN Term expires 1913 WALTER M. CHIPMAN 44 44 1914 LORENZO WOOD “ “ 1915 Trustees of Public Library. GEORGE BRAYTON Term expires 1913 EDWARD S. -

NSTAC Report to the President on Emerging Technologies Strategic Vision

THE PRESIDENT’S NATIONAL SECURITY TELECOMMUNICATIONS ADVISORY COMMITTEE NSTAC Report to the President on Emerging Technologies Strategic Vision July 14, 2017 President’s National Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... ES-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Scoping and Charge ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Approach ............................................................................................................................. 2 2.0 THE FUTURE TECHNOLOGY LANDSCAPE ..................................................... 2 2.1 Conceptual Maps of Forthcoming Technology .................................................................. 3 2.2 Taxonomy for Forthcoming Technology ............................................................................ 4 2.3 Two Technology Categories ............................................................................................... 5 2.4 Four Technology Trends ..................................................................................................... 6 3.0 TECHNOLOGY DISCUSSION ............................................................................. 8 3.1 Interconnectivity and Processing Power ............................................................................ -

Measuring the Heavens: Charles S. Peirce and Astronomical Photography

History of Photography ISSN: 0308-7298 (Print) 2150-7295 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/thph20 Measuring the Heavens: Charles S. Peirce and Astronomical Photography Aud Sissel Hoel To cite this article: Aud Sissel Hoel (2016) Measuring the Heavens: Charles S. Peirce and Astronomical Photography, History of Photography, 40:1, 49-66, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2016.1140329 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2016.1140329 Published online: 16 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 212 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=thph20 Download by: [Universidad Pablo de Olavide] Date: 22 September 2017, At: 02:01 Measuring the Heavens: Charles S. Peirce and Astronomical Photography Aud Sissel Hoel Taking its point of departure from the current digitisation of the Harvard Astronomical Plate Collection, this article follows the plates back to the time when the status of photography as a research tool for astronomers was still to be established. It focuses on Charles S. Peirce, who, while employed by the US Coast Survey, made astronomical observations and contributed to the deliberation over visual and photographic methods. Particular attention is paid to Peirce’s involvement in early explorations of photography’s potential as a measurement tool. The guiding assumption is that approaching photography as a tool, rather The archival work for this article was under- than as a sign or representation, offers new inroads into the old problem of taken while I was a Visiting Scholar in the photography’s revealing powers and its capacity to serve as a means of discovery Department of the History of Science at in science. -

Antique Equipment 1932

Antique Equipment 1932 DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS 1 9 3 2 0 Antique Equipment 1932 FOREWORD The Government College (Autonomous) was established in the year 1853 as a Zilla school and upgraded to provincial school in 1868, later it acquired status of a Second Grade College in 1873. Initially in 1891, it was affiliated to the Madras University and later it was affiliated to Andhra University in 1926. In 1930 the college started under graduate Course (B.Sc.,) with Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry as a stream and the department of Physics was established in 1930. At that time these equipment’s were brought from different countries like New Zealand, America, England, Japan, and Sweden. They were showcased in spe- cially designed “Teak Wood” boxes. Majority of the instruments and lab equipment are still under good working condition. We have one of the earliest known references to “LODESTONE” to study the magnetic properties. There is equipment which was made in 15th century namely “MARINE CHRONOMETER” used to measure accurately the time of a known fixed location which is particularly important for navigation. There exists a device namely “FIVE NEEDLE TELEGRAPH SYSTEM” which was developed by W. F. Cooke and Prof C. Wheatstone in 1837. We also have the first known practical telescopes invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 17th century, by using glass lenses, found to be used in both terrestrial and astronomical ob- servations which were still in good working condition. Some of the mod- els like “SECTIONAL MODEL OF THE LOCOMOTIVE ENGINE”, “SNELL AND POWELL'S WAVE MACHINES”, and “GRAMOPHONE PORTABLE MODE”, “GILLETT AND JOHNSTON (CROYDON) TOWER CLOCK” are the ancient equipment listed gives immense practical approach to the students.