Antique Equipment 1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces As Windows Into Experience: the Spiraled Conductor and Star Wheel Interrupter of Charles Grafton Page

| Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces as Windows into Experience | 123 | Sparks, Shocks and Voltage Traces as Windows into Experience: The Spiraled Conductor and Star Wheel Interrupter of Charles Grafton Page Elizabeth CAVICCHI a T Abstract When battery current flowing in his homemade spiraled conductor switched off, nineteenth century experimenter Charles Grafton Page saw sparks and felt shocks, even in parts of the spiral where no current passed. Reproducing his experiment today is improvisational: an oscilloscope replaces Page’s body; a copper star spinning through galinstan substitutes for Barlow’s wheel interrupter. Green and purple flashes accompanied my spinning wheel. Unlike what Page’s shocks showed, induced voltages probed across my spiral’s wider spans were variable, precipitating extensive explorations of its resonant fre - quencies. Redoing historical experiments extends our experience, fostering new observations about natural phenomena and experimental development. Keywords: electromagnetic induction, historical replication, Charles Grafton Page, exploratory learning, spiral, Barlow wheel, galinstan, autotransformer T Introduction real? Facing wires and wiggling magnetic needles firsthand, while trying to make sense of it, deepens Historical experiments come to us in fragments: our perspective; we become confused and curious handwritten data, published reports, and often non - (Cavicchi 2003). Redoing an experiment is not just a functioning apparatus. A further carry-over may per - check on facts, dates, whether Oersted’s needle went sist in ideas, procedures, materials and inventions east or west. It gives us access to experience congru - bearing imprints of the prior work. All these are clues ous with the past: “’to know an experimenter, you to something both more transitory and more coher - should replicate her study’” (Kurz 2001, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

A Chronological History of Electrical Development from 600 B.C

From the collection of the n z m o PreTinger JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 / A CHRONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF ELECTRICAL DEVELOPMENT FROM 600 B.C. PRICE $2.00 NATIONAL ELECTRICAL MANUFACTURERS ASSOCIATION 155 EAST 44th STREET NEW YORK 17, N. Y. Copyright 1946 National Electrical Manufacturers Association Printed in U. S. A. Excerpts from this book may be used without permission PREFACE presenting this Electrical Chronology, the National Elec- JNtrical Manufacturers Association, which has undertaken its compilation, has exercised all possible care in obtaining the data included. Basic sources of information have been search- ed; where possible, those in a position to know have been con- sulted; the works of others, who had a part in developments referred to in this Chronology, and who are now deceased, have been examined. There may be some discrepancies as to dates and data because it has been impossible to obtain unchallenged record of the per- son to whom should go the credit. In cases where there are several claimants every effort has been made to list all of them. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association accepts no responsibility as being a party to supporting the claims of any person, persons or organizations who may disagree with any of the dates, data or any other information forming a part of the Chronology, and leaves it to the reader to decide for him- self on those matters which may be controversial. No compilation of this kind is ever entirely complete or final and is always subject to revisions and additions. It should be understood that the Chronology consists only of basic data from which have stemmed many other electrical developments and uses. -

Listening to String Sound: a Pedagogical Approach To

LISTENING TO STRING SOUND: A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH TO EXPLORING THE COMPLEXITIES OF VIOLA TONE PRODUCTION by MARIA KINDT (Under the Direction of Maggie Snyder) ABSTRACT String tone acoustics is a topic that has been largely overlooked in pedagogical settings. This document aims to illuminate the benefits of a general knowledge of practical acoustic science to inform teaching and performance practice. With an emphasis on viola tone production, the document introduces aspects of current physical science and psychoacoustics, combined with established pedagogy to help students and teachers gain a richer and more comprehensive view into aspects of tone production. The document serves as a guide to demonstrate areas where knowledge of the practical science can improve on playing technique and listening skills. The document is divided into three main sections and is framed in a way that is useful for beginning, intermediate, and advanced string students. The first section introduces basic principles of sound, further delving into complex string tone and the mechanism of the violin and viola. The second section focuses on psychoacoustics and how it relates to the interpretation of string sound. The third section covers some of the pedagogical applications of the practical science in performance practice. A sampling of spectral analysis throughout the document demonstrates visually some of the relevant topics. Exercises for informing intonation practices utilizing combination tones are also included. INDEX WORDS: string tone acoustics, psychoacoustics, -

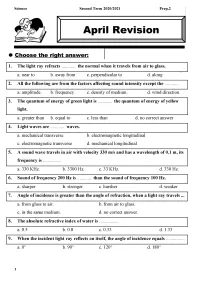

Choose the Correct Answer: 1

April Revision p2 1 2 3 4 5 Model Answer: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6 7 8 9 Model Answer: 10 April Revision – Prep 2 Choose the correct answer: 1. Sound waves travel through………………….. a. solids. b. liquids. c. gases. d. (a) , (b) and (c). 2. Sound waves do not travel through……………………… a. water. b. air. c. vacuum. d. wood. 3. The sound produced from the school bell is considered as…………….waves. a. longitudinal b. electromagnetic c. transverse d. a and c 4. All of the following indicate the nature of sound waves except that…………. a. it's mechanical longitudinal waves. b. it propagates as spheres of compressions and rarefactions. c. its velocity through air is 430 m/s. d. no correct answer. 5. Before using modern technology in communication, people in desert were putting their ears on the ground to hear the sound of horses of their enemies at very far places because.................... a. sense of hearing is stronger than sense of vision. b. the velocity of sound through solids (ground) is greater than that through air. c. sound travels faster than light. d. sound of horses' feet is very loud. 6. The sound velocity is measured in………………unit. a. Hertz b. meter c. decibel d. meter/second 7.Sound wave that propagates through air with velocity 330 meter/sec. and of wavelength 0.1 meter, its frequency equals……………….. a. 330 Kilo Hertz. b. 3300 Hertz. c. 33 Kilo Hertz. d. 330 Hertz. 8. All of these sounds are of uniform frequency except the sound of………………….. a. violin. -

Induction Coils A

7/25/2018 Induction Coil Induction Coils A. The Original Induction Coils The original induction coil was invented in 1836 by Nicholas Callan (1799-1864), a priest and the professor of natural philosophy at St. Patrick's College at Maynooth, County Kildare, Ireland. The basis for the coil was his large electromagnet with primary and secondary windings on the extremities of the U-shaped iron core. The primary circuit was interrupted (to get the required alternating current) by the mechanical Repeater that Callan designed. Callan's Great Induction Coil (left below) was left unfinished at Callan's death. The three secondary coils contain a total of 150,000 feet of fine iron wire. The primary coil is made of copper tape, wound around a core of iron wires. At the right below is the (incomplete) mechanism of interrupting the primary current. This apparatus, along with a similar one made by Callan which has only one secondary coil, is on display at the St. Patrick's College museum. The museum at St. Patrick's College contains parts of other early induction coils by Nicholas Callan. At the right are two long primary coils, and four toroidal secondary coils. The latter were insulated with a mixture of melted rosin and beeswax. Callan found that he could insulate 8000 ft of iron wire, 0.03 in. in diameter, per hour by passing it through this mixture and allowing it to harden on the wire, all in a continuous process. Independent of Callan, the American electrical inventor Charles Grafton Page (1812-1868) developed an induction coil in 1836. -

High Voltage Ignition Moved Back In

Rambling on about Ignition - High Voltage for Model Engine Ignition Article 3, 3/27/2007, © David Kerzel 2007 Rambling on about Ignition - High Voltage High voltage or high tension ignition was the first electric ignition used in engines. Ruhmkorff coils which are “buzz” coils originally made for electrical experiments were used. The Ruhmkorff coils were too fragile for practical engine operation and low voltage ignition was the preferred ignition on early engines. As time went on, higher reliability ignition was needed and high voltage ignition moved back in. The primary focus here is how these systems work electrically. In the last rambling, we examined how low voltage or low tension ignition works and how the coil stores energy and makes the spark or arc when the ignition contacts are opened. High voltage ignition is a continuation of those concepts. As you recall, the current flowing through the coil stores energy in the magnetic field around the coil and releases it when the switch interrupter or points are opened suddenly, causing an arc or spark as the energy stored in the coil is released. Michael Faraday made the first transformer in 1831 but thought it had no practical use. In 1836, Nicholas Callan invented the first induction coil to produce high voltage that was later improved by Heinrich Ruhmkorff in about 1851. In 1860 Lenoir was building spark ignition engines using Ruhmkorff coils. We need to start with a simple automotive type ignition coil which is a transformer. A transformer is two or more coils of wires that share a common magnetic field. -

Nicholas Callan- Is Found in a Paper of Mine Published in the London Philosophical Magazine for December 1836

Ph:s Educ 1'c 17 1982 Prlnted n G,?at Brlta r several of the members.., This was the first induction coil of great power ever seen outside the College of Maynooth. Thefirst notice of the discovery of the coil Nicholas Callan- is found in a paper of mine published in the London Philosophical Magazine for December 1836 , . , In priest, professor April 1837. I published in Sturgeon's Annuls of Elecruicir!, adescription of aninstrument which I devised for producing a rapid succession of electrical and scientist currents in the coil by rapidly making and breaking communication with the battery. Thus before April 1837 I hadcompleted the coil as amachine for producing a regular supply of electricity'. Michael T Casey In order to appraise Callan's researches in the field of electricity we shallconsider themunder various headings. all closely interrelated but not in chrono- logical order since many of them were carriedout simultaneously. NicholasJoseph Callan (1799-1864) was an Irish priest and professor of natural philosphy at Maynooth Seminary in Southern Ireland. He was a Electromagnetism and the induction coils pioneer in thestudy of electricity, andamong the Magnetism had intrigued man for centuries. With the devices that he constructed were batteries,electro- advent of batteries it was soon discovered that a coil magnetsand electric motors.The device that he of wire carrying an electric current has an associated seemed most proud of, however, was theinduction magnetic field and that when a current-carrying coil coil which he claimed to have invented. This claim is woundround an iron bar, the bar becomes was endorsed by Lord Rosse, President of the Royal magnetic. -

Origin of the Electric Motor

Origin of the Electric Motor JOSEPH C. MIGHALOWICZ MEMBER AIEE HE DAY that man Had it not been for the efforts of men like 1821—Michael Faraday dem- T molded the first wheel Davenport, De Jacobi, and Page, the benefits onstrated for the first time the from the sledlike skids of his of the electric motor would not be enjoyed possibility of motion by electro- magnetic means with the move- primitive wagon should be today. It is the purpose of this article to trace ment of a magnetic needle in a one of great commemoration, briefly the early history of the science of electro- field of force. had not its identity been lost motion and, in particular, to bring to light and 1829—-Joseph Henry, a teacher in the passing of time. Not to honor the inventor of the electric motor. of physics at the Albany Academy unlike the wheel and prob- in New York, constructed an elec- ably second only to the wheel, tromagnetic oscillating motor but considered it only a "philosophical the electric motor has been a toy." great benefactor to man and its history, too, slowly is 1833—Joseph Saxton, an American inventor, exhibited a magneto- being forgotten. Today, we hear very little, if anything, about Thomas Figure 1. Thomas Davenport, the blacksmith who invented the electric Davenport, inven- motor; or about De Jacobi, who propelled the first boat tor of the electric by means of an electric motor; or of Charles Page who motor successfully carried passengers on the first practical electric railway. Had it not been for the efforts of these men and others like them, the benefits of the electric motor probably would not be enjoyed today. -

Course Descriptions COURSES

Course Descriptions COURSES COURSES 2020-2021 • COLUMBIA COLLEGE CATALOG 151 COURSES: ABOUT COURSE DESCRIPTIONS About Course Descriptions term for lecture, or other required learning activities. The Total Student Course Numbering System Learning Hours listed for every course includes the number of hours spent in lecture plus the number of hours spent in lab (if applicable) NUMBER plus the recommended hours of study time. While the lecture and lab RANGE TYPE OF COURSE hours are fixed, the out-of-class study hours will vary from student to 1-99 CREDIT, BACCALAUREATE DEGREE/TRANSFER LEVEL student. Designated baccalaureate-level courses, transferable to four-year institutions and applicable to Associate Degree. Not all 1-99 Articulation of Courses with Other Colleges courses are UC-transferable. See “Transferability of Courses” on Columbia College articulates many of its courses with other public two- this page. and four-year colleges and universities in California. This allows units 70/170/270 CREDIT, SPECIAL TOPICS earned at Columbia College to satisfy academic requirements at other Instruction on a special topic within a broader discipline area schools. Please ask your counselor for information related to agree- (such as Child Development). Lecture and/or laboratory hours, ments establishing what courses will transfer and those that meet lower- units of credit, repeatability, and transferability may vary by division preparation for a baccalaureate major at a four-year university. offering. Check with the school to which student is transferring. 97 CREDIT, WORK EXPERIENCE Transferability of Courses Classes in career and technical fields in which students earn Courses that transfer to the California State University (CSU) and/or units of credit while working as paid or volunteer employees the University of California (UC) are designated at the end of the course in their field of study. -

Music and the Making of Modern Science

Music and the Making of Modern Science Music and the Making of Modern Science Peter Pesic The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Times by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pesic, Peter. Music and the making of modern science / Peter Pesic. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02727-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Science — History. 2. Music and science — History. I. Title. Q172.5.M87P47 2014 509 — dc23 2013041746 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Alexei and Andrei Contents Introduction 1 1 Music and the Origins of Ancient Science 9 2 The Dream of Oresme 21 3 Moving the Immovable 35 4 Hearing the Irrational 55 5 Kepler and the Song of the Earth 73 6 Descartes ’ s Musical Apprenticeship 89 7 Mersenne ’ s Universal Harmony 103 8 Newton and the Mystery of the Major Sixth 121 9 Euler: The Mathematics of Musical Sadness 133 10 Euler: From Sound to Light 151 11 Young ’ s Musical Optics 161 12 Electric Sounds 181 13 Hearing the Field 195 14 Helmholtz and the Sirens 217 15 Riemann and the Sound of Space 231 viii Contents 16 Tuning the Atoms 245 17 Planck ’ s Cosmic Harmonium 255 18 Unheard Harmonies 271 Notes 285 References 311 Sources and Illustration Credits 335 Acknowledgments 337 Index 339 Introduction Alfred North Whitehead once observed that omitting the role of mathematics in the story of modern science would be like performing Hamlet while “ cutting out the part of Ophelia. -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle.