Discrete/Continuous: Music and Media Theory After Kittler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Listening to String Sound: a Pedagogical Approach To

LISTENING TO STRING SOUND: A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH TO EXPLORING THE COMPLEXITIES OF VIOLA TONE PRODUCTION by MARIA KINDT (Under the Direction of Maggie Snyder) ABSTRACT String tone acoustics is a topic that has been largely overlooked in pedagogical settings. This document aims to illuminate the benefits of a general knowledge of practical acoustic science to inform teaching and performance practice. With an emphasis on viola tone production, the document introduces aspects of current physical science and psychoacoustics, combined with established pedagogy to help students and teachers gain a richer and more comprehensive view into aspects of tone production. The document serves as a guide to demonstrate areas where knowledge of the practical science can improve on playing technique and listening skills. The document is divided into three main sections and is framed in a way that is useful for beginning, intermediate, and advanced string students. The first section introduces basic principles of sound, further delving into complex string tone and the mechanism of the violin and viola. The second section focuses on psychoacoustics and how it relates to the interpretation of string sound. The third section covers some of the pedagogical applications of the practical science in performance practice. A sampling of spectral analysis throughout the document demonstrates visually some of the relevant topics. Exercises for informing intonation practices utilizing combination tones are also included. INDEX WORDS: string tone acoustics, psychoacoustics, -

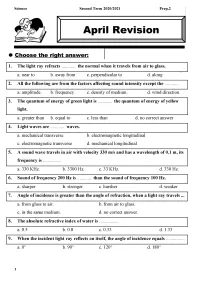

Choose the Correct Answer: 1

April Revision p2 1 2 3 4 5 Model Answer: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6 7 8 9 Model Answer: 10 April Revision – Prep 2 Choose the correct answer: 1. Sound waves travel through………………….. a. solids. b. liquids. c. gases. d. (a) , (b) and (c). 2. Sound waves do not travel through……………………… a. water. b. air. c. vacuum. d. wood. 3. The sound produced from the school bell is considered as…………….waves. a. longitudinal b. electromagnetic c. transverse d. a and c 4. All of the following indicate the nature of sound waves except that…………. a. it's mechanical longitudinal waves. b. it propagates as spheres of compressions and rarefactions. c. its velocity through air is 430 m/s. d. no correct answer. 5. Before using modern technology in communication, people in desert were putting their ears on the ground to hear the sound of horses of their enemies at very far places because.................... a. sense of hearing is stronger than sense of vision. b. the velocity of sound through solids (ground) is greater than that through air. c. sound travels faster than light. d. sound of horses' feet is very loud. 6. The sound velocity is measured in………………unit. a. Hertz b. meter c. decibel d. meter/second 7.Sound wave that propagates through air with velocity 330 meter/sec. and of wavelength 0.1 meter, its frequency equals……………….. a. 330 Kilo Hertz. b. 3300 Hertz. c. 33 Kilo Hertz. d. 330 Hertz. 8. All of these sounds are of uniform frequency except the sound of………………….. a. violin. -

Course Descriptions COURSES

Course Descriptions COURSES COURSES 2020-2021 • COLUMBIA COLLEGE CATALOG 151 COURSES: ABOUT COURSE DESCRIPTIONS About Course Descriptions term for lecture, or other required learning activities. The Total Student Course Numbering System Learning Hours listed for every course includes the number of hours spent in lecture plus the number of hours spent in lab (if applicable) NUMBER plus the recommended hours of study time. While the lecture and lab RANGE TYPE OF COURSE hours are fixed, the out-of-class study hours will vary from student to 1-99 CREDIT, BACCALAUREATE DEGREE/TRANSFER LEVEL student. Designated baccalaureate-level courses, transferable to four-year institutions and applicable to Associate Degree. Not all 1-99 Articulation of Courses with Other Colleges courses are UC-transferable. See “Transferability of Courses” on Columbia College articulates many of its courses with other public two- this page. and four-year colleges and universities in California. This allows units 70/170/270 CREDIT, SPECIAL TOPICS earned at Columbia College to satisfy academic requirements at other Instruction on a special topic within a broader discipline area schools. Please ask your counselor for information related to agree- (such as Child Development). Lecture and/or laboratory hours, ments establishing what courses will transfer and those that meet lower- units of credit, repeatability, and transferability may vary by division preparation for a baccalaureate major at a four-year university. offering. Check with the school to which student is transferring. 97 CREDIT, WORK EXPERIENCE Transferability of Courses Classes in career and technical fields in which students earn Courses that transfer to the California State University (CSU) and/or units of credit while working as paid or volunteer employees the University of California (UC) are designated at the end of the course in their field of study. -

Music and the Making of Modern Science

Music and the Making of Modern Science Music and the Making of Modern Science Peter Pesic The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected]. This book was set in Times by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited, Hong Kong. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pesic, Peter. Music and the making of modern science / Peter Pesic. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02727-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Science — History. 2. Music and science — History. I. Title. Q172.5.M87P47 2014 509 — dc23 2013041746 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Alexei and Andrei Contents Introduction 1 1 Music and the Origins of Ancient Science 9 2 The Dream of Oresme 21 3 Moving the Immovable 35 4 Hearing the Irrational 55 5 Kepler and the Song of the Earth 73 6 Descartes ’ s Musical Apprenticeship 89 7 Mersenne ’ s Universal Harmony 103 8 Newton and the Mystery of the Major Sixth 121 9 Euler: The Mathematics of Musical Sadness 133 10 Euler: From Sound to Light 151 11 Young ’ s Musical Optics 161 12 Electric Sounds 181 13 Hearing the Field 195 14 Helmholtz and the Sirens 217 15 Riemann and the Sound of Space 231 viii Contents 16 Tuning the Atoms 245 17 Planck ’ s Cosmic Harmonium 255 18 Unheard Harmonies 271 Notes 285 References 311 Sources and Illustration Credits 335 Acknowledgments 337 Index 339 Introduction Alfred North Whitehead once observed that omitting the role of mathematics in the story of modern science would be like performing Hamlet while “ cutting out the part of Ophelia. -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle. -

The Video Encyclopedia of Physics Demonstrations ™

The Video Encyclopedia of Physics Demonstrations™ Explanatory Material By: Dr. Richard E. Berg University of Maryland Scripts By: Brett Carroll University of Washington Equipment List By: John A. Davis University of Washington Editor: Rosemary Wellner Graphic Design: Wade Lageose/Art Hotel Typography: Malcolm Kirton Our special thanks to Jearl Walker for his assistance during the production of this series; to Gerhard Salinger for his support and encouragement during the production of this series; and to Joan Abend, without whom all this would not have been possible. We also wish to acknowledge the hard work of Laura Cepio, David DeSalvo, Michael Glotzer, Elizabeth Prescott and Maria Ysmael. This material is based upon work supported by The National Science Foundation under Grant Number MDR-9150092. © The Education Group & Associates, 1992. ISBN 1-881389-00-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to: The Education Group, 1235 Sunset Plaza Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90069. DISC TEN Chapter 23 Sound Production Demo 10-01 Guitar and Scope ...........................................................6 Demo 10-02 Sonometer ......................................................................8 Demo 10-03 Tuning Forks ................................................................10 -

Antique Equipment 1932

Antique Equipment 1932 DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS 1 9 3 2 0 Antique Equipment 1932 FOREWORD The Government College (Autonomous) was established in the year 1853 as a Zilla school and upgraded to provincial school in 1868, later it acquired status of a Second Grade College in 1873. Initially in 1891, it was affiliated to the Madras University and later it was affiliated to Andhra University in 1926. In 1930 the college started under graduate Course (B.Sc.,) with Mathematics, Physics & Chemistry as a stream and the department of Physics was established in 1930. At that time these equipment’s were brought from different countries like New Zealand, America, England, Japan, and Sweden. They were showcased in spe- cially designed “Teak Wood” boxes. Majority of the instruments and lab equipment are still under good working condition. We have one of the earliest known references to “LODESTONE” to study the magnetic properties. There is equipment which was made in 15th century namely “MARINE CHRONOMETER” used to measure accurately the time of a known fixed location which is particularly important for navigation. There exists a device namely “FIVE NEEDLE TELEGRAPH SYSTEM” which was developed by W. F. Cooke and Prof C. Wheatstone in 1837. We also have the first known practical telescopes invented in the Netherlands at the beginning of the 17th century, by using glass lenses, found to be used in both terrestrial and astronomical ob- servations which were still in good working condition. Some of the mod- els like “SECTIONAL MODEL OF THE LOCOMOTIVE ENGINE”, “SNELL AND POWELL'S WAVE MACHINES”, and “GRAMOPHONE PORTABLE MODE”, “GILLETT AND JOHNSTON (CROYDON) TOWER CLOCK” are the ancient equipment listed gives immense practical approach to the students. -

Psychoacoustics: a Brief Historical Overview

Psychoacoustics: A Brief Historical Overview William A. Yost From Pythagoras to Helmholtz to Fletcher to Green and Swets, a centu- ries-long historical overview of psychoacoustics. Postal: Speech and Hearing Science 1 Arizona State University What is psychoacoustics? Psychoacous- PO Box 870102 tics is the psychophysical study of acous- Tempe, Arizona 85287 tics. OK, psychophysics is the study of USA the relationship between sensory per- ception (psychology) and physical vari- Email: ables (physics), e.g., how does perceived [email protected] loudness (perception) relate to sound pressure level (physical variable)? “Psy- chophysics” was coined by Gustav Fech- ner (Figure 1) in his book Elemente der Psychophysik (1860; Elements of Psycho- physics).2 Fechner’s treatise covered at least three topics: psychophysical meth- ods, psychophysical relationships, and panpsychism (the notion that the mind is a universal aspect of all things and, as Figure 1. Gustav Fechner (1801-1887), “Father of Psychophysics.” such, panpsychism rejects the Cartesian dualism of mind and body). Today psychoacoustics is usually broadly described as auditory perception or just hearing, although the latter term also includes the biological aspects of hearing (physiological acoustics). Psychoacoustics includes research involving humans and nonhuman animals, but this review just covers human psychoacoustics. With- in the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), the largest Technical Committee is Physiological and Psychological Acoustics (P&P), and Psychological Acoustics is psychoacoustics. 1 Trying to summarize the history of psychoacoustics in about 5,000 words is a challenge. I had to make difficult decisions about what to cover and omit. My history stops around 1990. I do not cover in any depth speech, music, animal bioacoustics, physiological acoustics, and architectural acoustic topics because these may be future Acoustics Today historical overviews. -

Physics Demonstration Experiments at William Jewell College

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 230 434 SE 041 932 ' AUTHOR Hilton, Wallace A. Physics Demonstration Experiments at,William Jewell TITLE , College. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION American Association of Physics Teachers, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Jun 82 NOTE 114p. AVAILABLE FROMAmerican Association of Physics Teachers, Publications Department, Graftate Physics Building, S.U.N.Y., Stony Brook, NY 11794. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PitICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Acoustics; *College Science; *Demonstrations (Educational); *Electricity; *Heat; Higher Education; Mechanics (Physics); Nuclear Physics; Optics; *Physics; Science Education; *Science Equipment; Science Experiments IDENTIFIERS William Jewell College MO ABSTRACT Presented are descriptions (with photographs) of demonstration equipment purchased, assenibled, developed, and used at William Jewell College (Missouri) during the past 25 years: The descriptions are organized into the following topic areas:(1) mechanics; (2) heat; (3) waves, sound, and acoustics;'(4) electricity; (5) optics; and (6) omic and nuclear physics. This arrangement follows closely the reshmen-level textoby Harvey E. White ("Modern College Physic ) and is related to the sophomore-level text by F. 15< Sears and M. W. Zemansky("University Physics"). However, many gf the demonstrations presented may be used with any one of the goo freshmen/sophomore-level college physics textbooks currently av ilable. (11N) *********************************************************************** -

CAS Zh709wq3427.Pdf

THE CATGUT ACOUSTICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER * Number 24 > published semiannually November 1,1975 Margaret Tucker Saunders, widow of Frederick A. Saunders, the founder of the Catgut Acoustical Society, died last May. Those of us who were privileged to know Professor and Mrs. Saunders and visit with them in the big house overlooking the valley of the Connecticut River or later on Silverwood Terrace in South Hadley, Massachusetts, will remember many good times evenings of music, early morning bird watching, discussions about violins -- and testing, as well as wide-ranging interests in community and world af- fairs. After Professor Saunders died in 1963, Mrs. Saunders continued to extend her warm hospitality to her many friends to carry on her work in local politics, conserva- tion and school affairs, based on her deep conviction that citizens should take an active interest in the democratic process. She founded the "Know Your Town"- group in South Hadley and last year received the annual Lions Club Citizen of the Year Award at a spec- ial town meeting in her honor. A great lady has gone and we shall miss her. C.M. Hutchins ****,***#************.*.**.* We note also the death on June 10 of Professor W.H.Van Zoest of Eindhoven, who contri- buted to our last Newsletter an English translation of "Paul Gerhard Schmidt's Violoncello Ingrandito" (by W.C.deJong). We are**************pleased to announce that an index to articles*********from our Newsletters is in preparation. This edition will be comprehensive for all issues through No. 24 and will be mailed out with Newsletter No. 25 in May 1976 to all members in good standing. -

PIANOS Send for Catalogue, Containing Ove'l' 40 Dijfer.Ent Styles

• KUNKEL'S MUSICAL REVmW, MARCH, 1887. 81 MUS:IC BOOKS PUBLISHED :SY .OLIVER DITSON co. BOSTON., JY-[ASS .. • MUSIC BOOKS BOOKS OF THE OPERA! PIANO TEACHERS FOR do not need to be told that their pupils make the best pro JJI.ALE MIXED for gress when the best books are used. DITSON & CO.'S books and QUARTETS, Ditson & Co.'s editions of the operas have long been famous for teaching purposes are "tried and true" and stand in the £} u·, D T'ET OHOI.RS and for their fullness and completeness; being in many cases the very foremost rank. ~ .LJ.~a. ' only ones that contain all the music and all the libretto. The following are good editions of successful works: SOCIA L SINGS • THE GREATER OPERAS. Young People's Classics ~~. tl~~ic~~$l.~~teA.n 1~J~ FOR MALE VOICES. mirable collection of easy music that is good music, and Aida, ($2); Bohemian Girl, ($1); Carmen. ($2): Stradella, calculated to improve the taste, as well as furnish useful Am ph ion (5 books) $4. Arion (5 books) $4. Harmo• ($~); Dinorah, ($1); Faust, ($1); Lakme, ($L.60); Martha., ($1); practice to pupils in their 2d and 3d quarter on the piano. • ' Mignon. ($2.50): Field of Honor, ($2); Trovatore, ($l); Mar 52 pieces; by Lichner, Lange, Perabo, Kullak, Spindler, nla(5books)$2.50; Apollo$2; Boylston Club Col· itana, ($2); Mefistofele, ($2); Preciosa, (60 cts.); Conspirators, Oesten, Schumann and others. lectlon $1.50; Cross' Part Songs 60 cts.; Emer- ($1.25); Zenobia, ($2). son's Quartets and Choruses 60 cts.; Male LIGHT ENGLISH OPERAS.