Alternative Fingerings for Long-Foot Baroque Recorders J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis a Dissertation Submitted to the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University in Partial Fu

THE EXOTIC RHYTHMS OF DON ELLIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PEABODY INSTITUTE OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS BY SEAN P. FENLON MAY 25, 2002 © Copyright 2002 Sean P. Fenlon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Fenlon, Sean P. The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis. Diss. The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, 2002. This dissertation examines the rhythmic innovations of jazz musician and composer Don Ellis (1934-1978), both in Ellis’s theory and in his musical practice. It begins with a brief biographical overview of Ellis and his musical development. It then explores the historical development of jazz rhythms and meters, with special attention to Dave Brubeck and Stan Kenton, Ellis’s predecessors in the use of “exotic” rhythms. Three documents that Ellis wrote about his rhythmic theories are analyzed: “An Introduction to Indian Music for the Jazz Musician” (1965), The New Rhythm Book (1972), and Rhythm (c. 1973). Based on these sources a general framework is proposed that encompasses Ellis’s important concepts and innovations in rhythms. This framework is applied in a narrative analysis of “Strawberry Soup” (1971), one of Don Ellis’s most rhythmically-complex and also most-popular compositions. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to my dissertation advisor, Dr. John Spitzer, and other members of the Peabody staff that have endured my extended effort in completing this dissertation. Also, a special thanks goes out to Dr. H. Gene Griswold for his support during the early years of my music studies. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White

CURRICULUM VITAE Walter C. White Home Address: 23271 Rosewood Oak Park, MI 48237 (917) 273-7498 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.walterwhite.com EDUCATION Banff Centre of Fine Arts Summer Jazz Institute – Advanced study of jazz performance, improvisation, composition, and 1985-1988 arranging. Performances with Dave Holland. Cecil Taylor, Muhal Richard Abrahms, David Liebman, (July/August) Richie Beirach, Kenny Wheeler, Pat LaBarbara, Julian Priester, Steve Coleman, Marvin Smith. The University of Miami 1983-1986 Studio Music and Jazz, Concert Jazz Band, Monk/Mingus Ensemble, Bebop Ensemble, ECM Ensemble, Trumpet. The Juilliard School 1981-1983 Classical Trumpet, Orchestral Performance, Juilliard Orchestra. Interlochen Arts Academy (High School Grades 10-12) 1978-1981 Trumpet, Band, Orchestra, Studio Orchestra, Brass Ensemble, Choir. Interlochen Arts Camp (formerly National Music Camp) 8-weeks Summers, Junior Orchestra (principal trumpet), Intermediate Band (1st Chair), Intermediate Orchestra (principal), 1975- 1979, H.S. Jazz Band (lead trumpet), World Youth Symphony Orchestra (section 78-79, principal ’81) 1981 Henry Ford Community College Summer Jazz Institute Summer Classes in improvisation, arranging, small group, and big band performance. 1980 Ferndale, Michigan, Public Schools (Grades K-9) 1968-1977 TEACHING ACCOMPLISHMENTS Rutgers University, Artist-in-residence Duties included coaching jazz combos, trumpet master 2009-2010 classes, arranging classes, big band rehearsals and sectionals, private lessons, and five performances with the Jazz Ensemble, including performances with Conrad Herwig, Wynton Marsalis, Jon Faddis, Terrell Stafford, Sean Jones, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone, Mike Williams, and Paquito D’Rivera Newark, NY, High School Jazz Program Three day residency with duties including general music clinics and demonstrations for primary and secondary students, coaching of Wind Ensemble, Choir, Jan 2011 Jazz Vocal Ensemble, and two performances with the High School Jazz Ensemble. -

Universiv Micrmlms Internationcil

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microHlming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify m " '<ings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyriglited materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper le ft hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections w ith small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Band Director's Catalog

BAND DIRECTor’s CATALOG We make legends. A division of Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 www.conn-selmer.com AV4230 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eb Soprano, Harmony & Eb Alto Clarinets ....... 10 Bb Bass, EEb Bass & BBb Bass Clarinets ........... 11 308 Student Instruments Step-Up & Pro Saxophones .............................. 12-13 Step-Up & Pro Bb Trumpets .............................. 14 Piccolos & Flutes ...................................................... 1 Step-Up & Pro Cornets ..................................... 14 Oboes & Clarinets .................................................... 2 C Trumpets, Harmony Trumpets, Flugelhorns .... 15 Saxophones .............................................................. 3 Step-Up & Pro Trombones ................................ 16-17 204 Trumpets & Cornets .................................................. 4 Alto, Valve & Bass Trombones .......................... 18 Trombones ............................................................... 5 Double Horns .................................................. 19 PICCOLOS Single Horns ............................................................ 5 Baritones & Euphoniums .................................. 20 Educational Drum, Bell and Combo Kits .................. 6 BBb Tubas - Three Valve .................................... 21 ARMSTRONG Mallet Instruments .................................................... 6 BBb & CC Tubas - Four Valve ............................ 21 204 “USA” – Silver-plated headjoint and body, silver-plated -

Fomrhi-110.Pdf

v^uaneny INO. nu, iNovcmDer ^uuo FoMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 110 Christopher Goodwin 2 COMMUNICATIONS 1815 On frets and barring; some useful ideas David E McConnell 5 1816 Modifications to recorder blocks to improve sound production Peter N Madge 9 1817 What is wrong with Vermeer's guitar Peter Forrester 20 1818 A new addition to the instruments of the Mary Rose Jeremy Montagu 24 181*9 Oud or lute? - a study J Downing 25 1820 Some parallels in the ancestry of the viol and violin Ephraim Segerman 30 1821 Notes on the polyphont Ephraim Segerman 31 1822 The 'English' in English violette Ephraim Segerman 34 1823 The identity of tlie lirone Ephraim Segerman 35 1824 On the origins of the tuning peg and some early instrument name:s E Segerman 36 1825 'Twined' strings for clavichords Peter Bavington 38 1826 Wood fit for a king? An investigation J Downing 43 1827 Temperaments for gut-strung and gut-fretted instruments John R Catch 48 1828 Reply to Hebbert's Comm. 1803 on early bending method Ephraim Segerman 58 1829 Reply to Peruffo's Comm. 1804 on gut strings Ephraim Segerman 59 1830 Reply to Downing's Comm. 1805 on silk/catgut Ephraim Segerman 71 1831 On stringing of lutes (Comm. 1807) and guitars (Comms 1797, 8) E Segerman 73 1832 Tapered lute strings and added mas C J Coakley 74 1833 Review: A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance by Douglas Alton Smith (Lute Society of America, 2002) Ephraim Segerman 77 1834 Review: Die Renaissanceblockfloeten der Sammlung Alter Musikinstrumenten des Kunsthistorisches Museums (Vienna, 2006) Jan Bouterse 83 The next issue, Quarterly 111, will appear in February 2009. -

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

Listening to String Sound: a Pedagogical Approach To

LISTENING TO STRING SOUND: A PEDAGOGICAL APPROACH TO EXPLORING THE COMPLEXITIES OF VIOLA TONE PRODUCTION by MARIA KINDT (Under the Direction of Maggie Snyder) ABSTRACT String tone acoustics is a topic that has been largely overlooked in pedagogical settings. This document aims to illuminate the benefits of a general knowledge of practical acoustic science to inform teaching and performance practice. With an emphasis on viola tone production, the document introduces aspects of current physical science and psychoacoustics, combined with established pedagogy to help students and teachers gain a richer and more comprehensive view into aspects of tone production. The document serves as a guide to demonstrate areas where knowledge of the practical science can improve on playing technique and listening skills. The document is divided into three main sections and is framed in a way that is useful for beginning, intermediate, and advanced string students. The first section introduces basic principles of sound, further delving into complex string tone and the mechanism of the violin and viola. The second section focuses on psychoacoustics and how it relates to the interpretation of string sound. The third section covers some of the pedagogical applications of the practical science in performance practice. A sampling of spectral analysis throughout the document demonstrates visually some of the relevant topics. Exercises for informing intonation practices utilizing combination tones are also included. INDEX WORDS: string tone acoustics, psychoacoustics, -

A NEWS Summer Workshops Coming in April the Time Is Now

DA GAMBA SOCI ETY PACIFICA VOLIIME l8, NO. 7 MARCH 2oo5 A NEWS Summer Workshops Coming in April The time is now. Get out Call For Humor your calendar and turn to pages four and five for a Fchow a good viol joke? See it in sampling of this summer's print in the next issue of Gflmha workshops. Nezus. Send all viol-related humor to ]ulie Morrisett, editor, [email protected], or 412 John Dornenburg Arkansas St., San Francisco, CA Talks about his new CD Solo VI.oza dr Gamha, his love 94107. of jazz, and his future projects. Page six. These viols are made from very high-quality wood us- Lazar's Early Music ing techniques faithful to early string light constnic- Bill LAzar tion methods, which gives them a good timbre and a I started Lazar's Early Music in 1994 as a part-time beautiful appearance. Ribs, backs and necks are made business selling recorders. I gradu- of figured sycamore, and the tops and ally expanded over the years to the soundpost plate of spruce. The finger- point where I'm told I carry a larger boards are made in four parts, spruce variety of recorders than any other in the middle, thin plates of sycamore dealer in the US. on both sides and a thin ebony or birds- eye maple veneer on top, and tailpieces Last year, after going full-time, I of sycamore with ebony or birds-eye began selling viols and bows from maple veneer. The hook bar and tun- China, including Charlie Ogle' s ing pegs are made from ebony. -

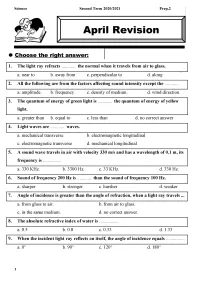

Choose the Correct Answer: 1

April Revision p2 1 2 3 4 5 Model Answer: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6 7 8 9 Model Answer: 10 April Revision – Prep 2 Choose the correct answer: 1. Sound waves travel through………………….. a. solids. b. liquids. c. gases. d. (a) , (b) and (c). 2. Sound waves do not travel through……………………… a. water. b. air. c. vacuum. d. wood. 3. The sound produced from the school bell is considered as…………….waves. a. longitudinal b. electromagnetic c. transverse d. a and c 4. All of the following indicate the nature of sound waves except that…………. a. it's mechanical longitudinal waves. b. it propagates as spheres of compressions and rarefactions. c. its velocity through air is 430 m/s. d. no correct answer. 5. Before using modern technology in communication, people in desert were putting their ears on the ground to hear the sound of horses of their enemies at very far places because.................... a. sense of hearing is stronger than sense of vision. b. the velocity of sound through solids (ground) is greater than that through air. c. sound travels faster than light. d. sound of horses' feet is very loud. 6. The sound velocity is measured in………………unit. a. Hertz b. meter c. decibel d. meter/second 7.Sound wave that propagates through air with velocity 330 meter/sec. and of wavelength 0.1 meter, its frequency equals……………….. a. 330 Kilo Hertz. b. 3300 Hertz. c. 33 Kilo Hertz. d. 330 Hertz. 8. All of these sounds are of uniform frequency except the sound of………………….. a. violin. -

MEISTERINSTRUMENTE Handcrafted Brass

MEISTERINSTRUMENTE handcrafted brass. A SYNTHESIS OF PASSION AND CRAFTSMANSHIP Wenn sich ein kleiner Musikali- reichische Musikhaus Schagerl gewöhnlicher Klang- und Ferti- enhandel mit Reparaturwerkstatt in Hörsdorf bei Mank, im Be- gungsqualität Orchestermusiker zu einer der weltweit bekanntes- zirk Melk seit drei Generationen aus aller Welt. 700 Instrumente ten Instrumentenmanufakturen ein- und dasselbe Firmenmotto verlassen mittlerweile jährlich entwickelt, steckt neben einer pflegt: In quality we trust! Die die Schagerl-Werkstätten und unbändigen Leidenschaft fürs hier von Meisterhand gefertig- etwa 90 Prozent davon gehen als Musizieren auch eines dahinter: ten Instrumente sind allesamt österreichische Exportschlager kompromisslose Qualität. Und so komplett in Eigenbau hergestellt rund um den Globus. IN QUALITY WE TRUST kommt es, dass das niederöster- und begeistern mit ihrer außer- A small music store with a re- the district of Melk, has main- workmanship. Seven hundred # MEISTERINSTRUMENTE pair shop grows into one of the tained the same company motto instruments leave the Schagerl world’s most well-known inst- for three generations: “In Qua- workshop each year, and ap- rument manufacturers. Powe- lity We Trust!” Instruments, proximately 90% become global red by an irrepressible passion built entirely “in-house”, and Austrian Export merchandise. for music and a belief in un- prepared by Master Craftsmen, compromising quality, Musik- inspire orchestral musicians haus Schagerl, in Lower-Aus- throughout the world with their tria, in Hörsdorf bei Mank, in exceptional sound quality and ROTARY VALVE TRUMPETS Die perfekte Balance in allen Registern, die leichte Ansprache und der Model „Berlin“Bb dunkle Klang ist ein unverwechselbares Merkmal dieser Modell-Reihe. Das Model „Berlin“ wurde in enger Zusammenarbeit mit Gábor Tarkövi (Solotrompeter der Berliner Philharmoniker) enwickelt: „Die „Berlin“ Bb und C Trompeten spielen sich sehr leicht, haben ein ausgewogenen, breiten, brillanter Klang gepaart mit einer ex- zellenten Stimmung. -

Course Descriptions COURSES

Course Descriptions COURSES COURSES 2020-2021 • COLUMBIA COLLEGE CATALOG 151 COURSES: ABOUT COURSE DESCRIPTIONS About Course Descriptions term for lecture, or other required learning activities. The Total Student Course Numbering System Learning Hours listed for every course includes the number of hours spent in lecture plus the number of hours spent in lab (if applicable) NUMBER plus the recommended hours of study time. While the lecture and lab RANGE TYPE OF COURSE hours are fixed, the out-of-class study hours will vary from student to 1-99 CREDIT, BACCALAUREATE DEGREE/TRANSFER LEVEL student. Designated baccalaureate-level courses, transferable to four-year institutions and applicable to Associate Degree. Not all 1-99 Articulation of Courses with Other Colleges courses are UC-transferable. See “Transferability of Courses” on Columbia College articulates many of its courses with other public two- this page. and four-year colleges and universities in California. This allows units 70/170/270 CREDIT, SPECIAL TOPICS earned at Columbia College to satisfy academic requirements at other Instruction on a special topic within a broader discipline area schools. Please ask your counselor for information related to agree- (such as Child Development). Lecture and/or laboratory hours, ments establishing what courses will transfer and those that meet lower- units of credit, repeatability, and transferability may vary by division preparation for a baccalaureate major at a four-year university. offering. Check with the school to which student is transferring. 97 CREDIT, WORK EXPERIENCE Transferability of Courses Classes in career and technical fields in which students earn Courses that transfer to the California State University (CSU) and/or units of credit while working as paid or volunteer employees the University of California (UC) are designated at the end of the course in their field of study.