Topicality and the Typology of Predicative Possession Received May 11, 2018; Revised December 15, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Left Dislocated and Tripartite Verbless Clauses in Biblical Hebrew1

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 48, 2017, 223-238 doi: 10.5774/48-0-293 At the interface of syntax and prosody: Differentiating left dislocated and tripartite verbless clauses in Biblical Hebrew1 Jacobus A. Naudé Department of Hebrew, University of the Free State, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé Department of Hebrew, University of the Free State, South Africa [email protected] Abstract The so-called tripartite verbless clause in Biblical Hebrew consists of two nominal phrases and a pronominal element. Three analyses of the pronominal element have been advanced, each with implications for understanding the structure of the sentence. A first approach has been to view the pronominal element as a copular constituent, which serves only to link the two nominal constituents in a predication (Albrecht 1887, 1888; Brockelman 1956; and Kummerouw 2013). A second approach has been to view the pronominal element as the resumptive element of a dislocated constituent (Gesenius, Kautzsch and Cowley 1910; Andersen 1970; Zewi 1996, 1999, 2000; Joüon-Muraoka 2006). A third approach combines the first and second approaches and is represented by the work of Khan (1988, 2006) and Holmstedt and Jones (2014). A fourth approach views the pronominal element as a “last resort” syntactic strategy—the pronominal element is a pronominal clitic, which provides agreement features for the subject (Naudé 1990, 1993, 1994, 1999, 2002). The pronominal element is obligatory when the nominal predicate is a referring noun phrase—the pronominal clitic is used to prevent ambiguity in the assignment of subject and predicate (see Doron 1986; Borer 1983). -

Study on Phoniatrics Directed at Chinese English Learners from Regions of Prominent Dialects in Anhui Province

Education Journal 2015; 4(5): 294-297 Published online November 20, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/edu) doi: 10.11648/j.edu.20150405.26 ISSN: 2327-2600 (Print); ISSN: 2327-2619 (Online) Study on Phoniatrics Directed at Chinese English Learners from Regions of Prominent Dialects in Anhui Province Wang Hua-zhen School of Foreign Languages, Anhui Sanlian University, Hefei, China Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Wahg Hua-zhen. Study on Phoniatrics Directed at Chinese English Learners from Regions of Prominent Dialects in Anhui Province. Education Journal . Vol. 4, No. 5, 2015, pp. 294-297. doi: 10.11648/j.edu.20150405.26 Abstract: Based on Optimality theory and the long-term phonetics teaching and experimental teaching ,the author probes into the study on optimality theory in English phonetics acquisition of students from Anhui Province with the phonetic investigation. Try to explore and analyze the phonetic phenomenon of negative transfer from Anhui dialects. Then some advices are given to the practical phonetic teaching. summarize students' acquisition of English dialect speech difficulties and pronunciation error characteristics, and try to find a viable Phonetic teaching approach as to promote education. Keywords: Optimality Theory, Dialects in Anhui Province, English Pronunciation, Correcting Strategies 1. Introduction 1.2. The Content of Optimality Theory 1.1. The Connotation of Optimality Theory The basic operation mechanism in the phonology about the Optimality Theory as follows: "Inclusive Principles" and The Optimality Theory is abbreviated form of OT Theory, "Analysis Of Randomness Principle.", Gen generating means Originally proposed in 1991 by the American linguist Prince to generate an unlimited number of candidates on the basis of and Smolensky in the American Society of phonological the specific entry; These candidates entered Eval evaluation Arizona State University. -

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles Mcdonald All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles McDonald All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without, limitation, preservation or instruction. GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Richard Charles McDonald December 2014 APPROVAL SHEET GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR Richard Charles McDonald Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Russell T. Fuller (Chair) __________________________________________ Terry J. Betts __________________________________________ John B. Polhill Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Nancy. Without her support, encouragement, and love I could not have completed this arduous task. I also dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Charles and Shelly McDonald, who instilled in me the love of the Lord and the love of His Word. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.............................................................................................vi LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................vii -

Research on the Propagation Effect of the Painters Art in the Tang Dynasty

2019 3rd International Workshop on Arts, Culture, Literature and Language (IWACLL 2019) Research on the propagation effect of the painters art in the Tang Dynasty Jin Xiaoyun Art College of Gansu University of Political Science and Law, Lanzhou 730070, China Keywords: Tang Dynasty; painters art; spread; effect; research Abstract: As the highest peak of feudal society development in Chinese history, the glory of the Tang Dynasty is reflected in all aspects, and painting is part of it. Throughout the painters art in the Tang Dynasty, the magnificent and positive spirits are revealed everywhere. It is one of the most brilliant pearls in the history of Chinese art, and it has written generous colour for the splendor of world culture. The creative environment of the Tang Dynasty painters was relatively free and there were many ways of communication. Therefore, many famous art and works were spread at that time, which had a great impact on the people at that time and in later generations. This paper mainly studies the spread and effect of the painters art in the Tang Dynasty. 1. Introduction The Tang Dynasty has achieved unprecedented development in economic, political, and cultural aspects, and which constituted the prosperous Tang Dynasty that the Chinese nation is proud of. The art of painting also showed an unprecedented prosperity in the Tang Dynasty. The painters art of the Tang Dynasty was supported by the famous masters of the Tang Dynasty. Because of the powerful national power and prosperous economy, the scale and artistic reached the level that the former generation could not match. -

In Language and Linguistics Compass 7.1:39-57 (2013) Survey Of

In Language and Linguistics Compass 7.1:39-57 (2013) Survey of Chinese Historical Syntax Part I: Pre-Archaic and Archaic Chinese Edith Aldridge, University of Washington Abstract This is the first of two articles presenting a brief overview of Chinese historical syntax from the Pre-Archaic period to Middle Chinese. The phenomena under examination in the two papers are primarily aspects of pre-medieval grammar which differ markedly from modern Chinese varieties, specifically fronting of object NPs to preverbal position, the asymmetry between subject and object relative clause formation, and the encoding of argument structure alternations like active and passive. I relate each of these characteristics to morphological distinctions on nouns, verbs, or pronouns which are either overtly represented in the logographic writing system in Archaic Chinese or have been reconstructed for (Pre-)Archaic Chinese. In the second part of this series, I discuss the changes in the Archaic Chinese grammatical features and correlate these innovations with the loss of the (Pre-)Archaic Chinese morphology. The main goal of these articles is to highlight a common denominator, i.e. the morphology, which enables a systemic view of pre-medieval Chinese and the changes which have resulted in the striking differences observed in Middle Chinese and beyond. 1. Introduction This paper is the first in a two-part series on grammatical features of Chinese from the earliest attested records over a millennium before the Common Era (BCE) to Middle Chinese of approximately the 5th century of the Common Era (CE). The first installment introduces characteristics of Pre-Archaic and Archaic Chinese which distinguish it from both Middle Chinese and modern Chinese varieties, in particular Standard Mandarin. -

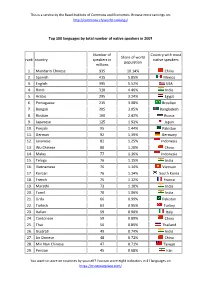

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Language, Myth, Histories, and the Position of the Phong in Houaphan

Neither Kha, Tai, nor Lao: Language, Myth, Histories, and the Position of the Phong in Houaphan Oliver Tappe1 Nathan Badenoch2 Abstract In this paper we explore the intersections between oral and colonial history to re-examine the formation and interethnic relations in the uplands of Northern Laos. We unpack the historical and contemporary dynamics between “majority” Tai, “minority” Kha groups and the imagined cultural influence of “Lao” to draw out a more nuanced set of narratives about ethnicity, linguistic diversity, cultural contact, historical intimacy, and regional imaginings to inform our understanding of upland society. The paper brings together fieldwork and archival research, drawing on previous theoretical and areal analysis of both authors. 1. Introduction The Phong of Laos are a small group of 30,000 people with historical strongholds in the Sam Neua and Houamuang districts of Houaphan province (northeastern Laos). They stand out among the various members of the Austroasiatic language family – which encompass 33 out of the 50 ethnic groups in Laos – as one of the few completely Buddhicized groups. Unlike their animist Khmu neighbours, they have been Buddhist since precolonial times (see Bouté 2018 for the related example of the Phunoy, a Tibeto-Burman speaking group in Phongsaly Province). In contrast to the Khmu (Évrard, Stolz), Rmeet (Sprenger), Katu (Goudineau, High), Hmong (Lemoine, Tapp), Phunoy (Bouté), and other ethnic groups in Laos, the Phong still lack a thorough ethnographic study. Joachim Schliesinger (2003: 236) even called them “an obscure people”. This working paper is intended as first step towards exploring the history, language, and culture of this less known group. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

TURBANS and TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal

TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Social Science – Honours in the Department of Historical Studies, Faculty of Human Science, University of Natal 2002 University of Natal Abstract TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY Supervised by: Professor Jeff Guy Department of Historical Studies This dissertation is concerned with an historical examination of Indian Interpreters in the British Colony of Natal during the period, 1880 to 1910. These civil servants were intermediaries between the Colonial State and the wider Indian population, who apart from the ‘Indentureds’, included storekeepers, traders, politicians, railway workers, constables, court messengers, teachers and domestic servants. As members of an Indian elite and the Natal Civil Service, they were pioneering figures in overcoming the shackles of Indenture but at the same time they were active agents in the perpetuation of colonial oppression, and hegemonic imperialist ideas. Theirs was an ambiguous and liminal position, existing between worlds, as Occidentals and Orientals. Contents Acknowledgements iii List of Images iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 8 Chapter One – Indenture, Interpreters and Empire 13 Chapter Two – David Vinden 30 Chapter Three – Cows and Heifers 51 Chapter Four – A Diabolical Conspiracy 74 Conclusion 94 Appendix 98 Bibliography 124 Acknowledgments Out of a sea-bed of my search years I have put together again a million fragments of my brother’s ancient mirror… and as I look deep into it I see a million shades of fractured brown, merging into an unstoppable tide… David Campbell The history of Indians in Natal is one that is incomplete and developing. -

NTOU Chinese Grammar Checker for CGED Shared Task

NTOU Chinese Grammar Checker for CGED Shared Task Chuan-Jie Lin and Shao-Heng Chen Department of Computer Science and Engineering National Taiwan Ocean University No 2, Pei-Ning Road, Keelung 202, Taiwan R.O.C. {cjlin, shchen.cse}@ntou.edu.tw However in NLPTEA2-CGED (Lee et al., Abstract 2015), it is required to report the location of a detected error. To meet this requirement, two Grammatical error diagnosis is an new systems were proposed in this paper. The essential part in a language-learning first one was an adaptation of the classifier tutoring system. Participating in the developed by machine learning where location second Chinese grammar error detection information was considered. The second one task, we proposed a new system which employed hand-crafted rules to predict the measures the likelihood of sentences locations of errors. generated by deleting, inserting, or We also designed two scoring functions to exchanging characters or words. Two predict the likelihood of a sentence. Totally sentence likelihood functions were three runs were submitted to NLPTEA2-CGED proposed based on frequencies of space- task. Evaluation results showed that rule-based removed version of Google n-grams. systems achieved better performance. More The best system achieved a precision of details are described in the rest of this paper. 23.4% and a recall of 36.4% in the This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 identification level. gives the definition of Chinese grammatical error diagnosis task. Section 3 delivers our newly 1 Introduction proposed n-gram statistics-based systems. Section 4 gives a brief description about our Although that Chinese grammars are not defined SVM classifier. -

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord

Sentential Negation and Negative Concord Published by LOT phone: +31.30.2536006 Trans 10 fax: +31.30.2536000 3512 JK Utrecht email: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration: Kasimir Malevitch: Black Square. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. ISBN 90-76864-68-3 NUR 632 Copyright © 2004 by Hedde Zeijlstra. All rights reserved. Sentential Negation and Negative Concord ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Prof. Mr P.F. van der Heijden ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op woensdag 15 december 2004, te 10:00 uur door HEDZER HUGO ZEIJLSTRA geboren te Rotterdam Promotiecommissie: Promotores: Prof. Dr H.J. Bennis Prof. Dr J.A.G. Groenendijk Copromotor: Dr J.B. den Besten Leden: Dr L.C.J. Barbiers (Meertens Instituut, Amsterdam) Dr P.J.E. Dekker Prof. Dr A.C.J. Hulk Prof. Dr A. von Stechow (Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen) Prof. Dr F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Voor Petra Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................V 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................1 1.1 FOUR ISSUES IN THE STUDY OF NEGATION.......................................................1 -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence.